A Queer Investigation of the Broadwayfication of Disney the Term

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2012 Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values Allyson Scott California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Scott, Allyson, "Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values" (2012). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 391. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/391 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social and Behavioral Sciences Department Senior Capstone California State University, Monterey Bay Almost There: A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values Dr. Rebecca Bales, Capstone Advisor Dr. Gerald Shenk, Capstone Instructor Allyson Scott Spring 2012 Acknowledgments This senior capstone has been a year of research, writing, and rewriting. I would first like to thank Dr. Gerald Shenk for agreeing that my topic could be more than an excuse to watch movies for homework. Dr. Rebecca Bales has been a source of guidance and reassurance since I declared myself an SBS major. Both have been instrumental to the completion of this project, and I truly appreciate their humor, support, and advice. -

Providence Place Showcase

Providence Place Showcase Cinema 10 Providence Place, Providence, RI 02903 1.800.315.4000 http://www.nationalamusements.com/theatres/current_theatre.asp?theatre=8641 Tickets: $10 general admission Wed., 8/11: 7:00 p.m. The Caretaker 3D Directed by Sean Isroelit 5 min. U S A, 2009 Set in the late 1930's, The Caretaker 3D is about the man who maintained the 4000 light bulbs which once outlined the HOLLYWOODLAND sign at night. A high profile period project that reflects how Hollywood films reach out to the world, The Caretaker 3D stars Hollywood legend Dick Van Dyke as the mystical custodian. Waking Sleeping Beauty Directed by Don Hahn 86 min. U S A, 2009 Waking Sleeping Beauty is no fairytale. It is a story of clashing egos, out of control budgets, escalating tensions… and one of the most extraordinary creative periods in animation history. Director Don Hahn and producer Peter Schneider, key players at Walt Disney Studios Feature Animation department during the mid1980s, offer a behind—the—magic glimpse of the turbulent times the Animation Studio was going through and the staggering output of hits that followed over the next ten years. Artists polarized between the hungry young innovators and the old guard who refused to relinquish control, mounting tensions due to a string of box office flops, and warring studio heads create the backdrop for this fascinating story told with a unique and candid perspective from those that were there. Through interviews, internal memos, home movies, and a cast of characters featuring Michael Eisner, Jeffrey Katzenberg, and Roy Disney, alongside an amazing array of talented artists that includes Don Bluth, John Lasseter, and Tim Burton, Waking Sleeping Beauty shines a light on Disney Animation’s darkest hours, greatest joys and its improbable renaissance. -

How Are Gender Roles Enabled and Constrained in Disney Music, During Classic Disney, the Disney Renaissance, and Modern Disney?

Someday my Prince Will Come: How are gender roles enabled and constrained in Disney Music, during Classic Disney, the Disney Renaissance, and Modern Disney? By Lauren Marie Hughes A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2016 Approved by _______________________________ Advisor: Dr. James Thomas _______________________________ Reader: Dr. Kirsten Dellinger _______________________________ Reader: Dr. Marvin King © 2016 Lauren Marie Hughes ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii DEDICATIONS To my parents, there are no words for how thankful I am for you. I don’t know how I would have succeeded in life without your love, support, and encouragement. To Nora, Sam, Maureen, and Mary Kate, thank you for being such an inspiration. I can only hope to make you all as proud as you make me. To Chance, thank you for being there for me through all of the highs and lows of this project. I am so lucky to call you mine. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To JT, thank you so much for lending your time to this project for the last year and a half, thank you for having a passion for the project that left me encouraged after every meeting, and thank you for always ensuring me that I could do this and do it well, even when I was ready to call it quits. You are awesome. To Dr. Dellinger and Dr. King, thank you so much for taking an interest in my thesis and being on my thesis committee. I am so privileged to have such outstanding people on my team. -

The Complete Diney Film Check List

Seen Own it it The Complete Diney Film Check List $1,000,000 Duck, The (G) 10 Things I Hate About You (PG-13) 101 Dalmatians (1996 Live Action)(G) 102 Dalmatians (G) 13th Warrior, The (R) 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (G) 25th Hour (R) 3 Ninjas (PG) 6th Man, The (PG-13) Absent-Minded Professor, The (G) Adventures in Babysitting (PG-13) Adventures of Bullwhip Griffin, The Adventures of Huck Finn (PG) Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, The (G) African Cats: Kingdom of Courage(G) African Lion, The Air Bud (PG) Air Up There, The (PG) Aladdin (2019 Live Action) Aladdin (G) Alamo, The (PG-13) Alan Smithee Film, An: Burn, Hollywood, Burn (R) Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day (PG) Alice in Wonderland (G) Alice in Wonderland (2010 Live Action) (PG) Alice Through the Looking Glass (PG) Aliens of the Deep (G) Alive (R) Almost Angels America’s Heart & Soul (PG) American Werewolf in Paris, An (R) Amy (G) An Innocent Man (R) Angels in the Outfield (PG) Angie (R) Annapolis (PG-13) Another Stakeout (PG-13) Ant-Man (PG-13) Ant-Man and The Wasp (PG-13) Apocalypto (R) Apple Dumpling Gang, The (G) Apple Dumpling Gang Rides Again, The (G) Arachnophobia (PG-13) Aristocats, The (G) Armageddon (PG-13) Around the World in 80 Days (PG) Artemis Fowl Aspen Extreme (PG-13) Associate, The (PG-13) Atlantis: The Lost Empire (PG) Avengers: Age of Ultron (PG-13) Avengers: End Game Avengers: Infinity War (PG-13) Babes in Toyland Baby…Secret of the Lost Legend (PG) Bad Company (PG-13) Bad Company (R) Bambi (G) Barefoot Executive, The (G) Beaches -

2010 Flickers: Rhode Island International Film Festival

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 2010 FLICKERS: RHODE ISLAND INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL MEDIA RELEASE For Details, Photographs or Videos about Flickers News Releases Contact: Lily Chase-Lubitz, Media Coordinator [email protected] • 401.861-4445 Disney’s Acclaimed “Waking Sleeping Beauty” comes to the Rhode Island International Film Festival Film Chronicles the Rebirth of the Disney Animation Studio from “The Little Mermaid” to the Pixar Revolution; Film’s Writer to Attend (PROVIDENCE, RI • July 27, 2010) --- Fans of Disney animation are in for a treat this August when FLICKERS: Rhode Island International Film Festival (RIIFF) presents the regional premiere of the critically acclaimed documentary, “Waking Sleeping Beauty.” The film will be screened on Wednesday, August 11th at 7:00 p.m. at the Providence Showcase Cinema 16, and again on Saturday, August 14th, 7:00 p.m. at the Opera House Cinema in Newport. Tickets are $10 and can be purchased in advance or at the door. “Waking Sleeping Beauty” brilliantly fuses interviews, internal memos, home movies, and a memorable cast of characters who brought about what would become the Disney animation revolution: Michael Eisner, Jeffrey Katzenberg, and Roy Disney, Don Bluth, John Lasseter and Tim Burton. The film shines a light on Disney Animation’s darkest hours, greatest joys and its incredible renaissance. “The film chronicles the extremely dramatic time from 1984 to 1994 when a perfect storm of people and circumstances changed the face of feature animation forever. It is a wonderfully entertaining story of clashing egos, out-of-control budgets, escalating tensions... and one of the most extraordinary creative periods in animation history.” said Ron Tippe, RIIFF Producing Director, who worked with Walt Disney Feature Animation on the Oscar-nominated short, “RUNAWAY BRAIN,” and he managed the Disney Animation Studio in Paris, France. -

In Order of Release

Animated(in order Disney of release) Movies Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Treasure Planet Pinocchio The Jungle Book 2 Dumbo Piglet's Big Movie Bambi Finding Nemo Make Mine Music Brother Bear The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad Teacher's Pet Cinderella Home on the Range Alice in Wonderland The Incredibles Peter Pan Pooh's Heffalump Movie Lady and the Tramp Valiant Sleeping Beauty Chicken Little One Hundred and One Dalmatians The Wild The Sword in the Stone Cars The Jungle Book The Nightmare Before Christmas 3D TNBC The Aristocats Meet the Robinsons Robin Hood Ratatouille The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh WALL-E The Rescuers Roadside Romeo The Fox and the Hound Bolt The Black Cauldron Up The Great Mouse Detective A Christmas Carol Oliver & Company The Princess and the Frog The Little Mermaid Toy Story 3 DuckTales: Treasure of the Lost Lamp Tangled The Rescuers Down Under Mars Needs Moms Beauty and the Beast Cars 2 Aladdin Winnie the Pooh The Lion King Arjun: The Warrior Prince A Goofy Movie Brave Pocahontas Frankenweenie Toy Story Wreck-It Ralph The Hunchback of Notre Dame Monsters University Hercules Planes Mulan Frozen A Bug's Life Planes: Fire & Rescue Doug's 1st Movie Big Hero 6 Tarzan Inside Out Toy Story 2 The Good Dinosaur The Tigger Movie Zootopia The Emperor's New Groove Finding Dory Recess: School's Out Moana Atlantis: The Lost Empire Cars 3 Monsters, Inc. Coco Return to Never Land Incredibles 2 Lilo & Stitch Disney1930s - 1960s (in orderMovies of release) Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Ten Who Dared Pinocchio Swiss Family Robinson Fantasia One Hundred and One Dalmatians The Reluctant Dragon The Absent-Minded Professor Dumbo The Parent Trap Bambi Nikki, Wild Dog of the North Saludos Amigos Greyfriars Bobby Victory Through Air Power Babes in Toyland The Three Caballeros Moon Pilot Make Mine Music Bon Voyage! Song of the South Big Red Fun and Fancy Free Almost Angels Melody Time The Legend of Lobo So Dear to My Heart In Search of the Castaways The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. -

Born in Baltimore, Howard Ashman Grew up Loving Musical Theatre

SYNOPSIS: Born in Baltimore, Howard Ashman grew up loving musical theatre. After studying at Boston University and Goddard College, he earned his Masters degree at University of Indiana. In 1978, Howard came to New York and opened a Off-Off-Broadway theatre, which he initially subsidized by writing cover copy for book publishers before it became the talk of the town. His success adapting a Kurt Vonnegut novel, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, led Howard and his song writing partner, Alan Menken, to adapt the Roger Corman film Little Shop of Horrors for the stage—which quickly became a cultural phenomenon in New York City and beyond. His success led him to a dream collaboration with A Chorus Line composer Marvin Hamlisch on the musical Smile. But the production was plagued with changes, and after investors bailed it soon crashed when it opened on Broadway. Humiliated, Howard fled Broadway and answered Disney Studio Head Jeffrey Katzenberg’s call to come to California and work for Disney. Howard immediately gravitated to animation where he could bring his musical theatre skills to a new medium. Menken joined him and the result was the Oscar winning score and songs for THE LITTLE MERMAID. But in the background of the triumph of MERMAID, Howard was diagnosed with AIDS, at a time when the disease was untreatable and a virtual death sentence. Howard kept his illness a secret and instead of slowing down, dug into two new musicals for Disney. The first, ALADDIN, yielded brilliant song demos inspired by Fats Waller, but the story crashed and went into rewrites. -

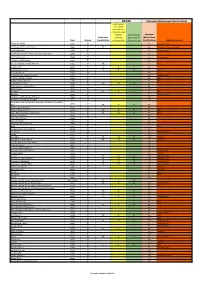

'Twas the Night 2001 D ACCM's GUIDE 1 Chance 2 Dance 2014 N

Disney / Australian Kijkwijzer Year Netflix Classification ACCM (Netherlands) Kijkwijzer reasons ‘Twas the Night 2001 D 6+ Violence; Fear ACCM's GUIDE 1 Chance 2 Dance 2014 N 12+ Violence 10 Things I Hate About You 1997 D PG 6+ Violence; Coarse language Content is age appropriate for children this age 101 Dalmatians II: Patch’s London 2003 D Adventure All 101 Dalmatians 1996 D 6+ Violence; Fear Some content may not be appropriate for children this age. Parental guidance recommended 102 Dalmatians 2000 D 6+ Violence; Fear 12 Dates of Christmas 2011 D All 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea 1954 D 9+ Fear 3 Ninjas: Kick Back 1994 N 6+ Violence; Fear 48 Christmas Wishes 2017 N All A Bug’s Life 1993 D All A Christmas Prince 2017 N 6+ Fear A Dog's Purpose 2017 N PG 10 13 A Dogwalker's Christmas Tale 2015 N zz A Goofy Movie 1995 D All A Kid in King Arthur’s Court 1995 D 6+ Violence; Fear A Ring of Endless Light 2002 D 6+ Fear A Second Chance 2011 N PG A StoryBots Christmas 2017 N All Adventures in Babysitting 2016 D All African Cats 2011 D All Aladdin 2019 D PG 5 9 9+ Fear Aladdin and the King of Thieves 1996 D All Albion: The Enchanted Stallion 2016 N 9+ Fear; Coarse language Alice in Wonderland 2010 D PG 12 15 9+ Fear Alice Through the Looking Glass 2016 D PG 10 13 9+ Fear Aliens of the Deep 2005 D All Alley Cats Strike! 2000 D All Almost Angels D All Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Road 2015 N Chip PG 7 8 America’s Heart & Soul D All Amphibia D 6+ Fear Amy 1981 D 9+ Fear An Extremely Goofy Movie D All Andi Mack D All Angela's Christmas 2018 N G Annabelle -

Deconstructing Disney's Divas: a Critique of the Singing Princess As Filmic Trope

48 Liske Potgieter Deconstructing Ms Liske Potgieter, Music Department, Disney’s divas: a South Campus, PO Box 77000, NMM 6031; critique of the singing E-mail: liskepotgieter@ gmail.com princess as filmic trope Zelda Potgieter First submission: 2 June 2016 Prof Zelda Potgieter, Acceptance: 8 December 2016 Music Department, South Campus, PO Box This article contributes to the discourse of the body 77000, NMM 6031; and the voice in feminist psychoanalytic film theory Email: zelda.potgieter@ by exploring the currently under-theorised notion nmmu.ac.za of the singing body in particular, as this notion finds DOI: http://dx.doi. manifestation in Disney’s Singing Princess as filmic org/10.18820/24150479/ trope. Analyses of vocal musical coding follow her aa48i2.2 trajectory across 13 Disney princess films to reveal ISSN: ISSN 0587-2405 deeper insight into what she sings, how she sings, and e-ISSN: 2415-0479 why she sings. In this manner, it is argued, the Singing Acta Academica • 2016 48(2): Princess gradually emerges from her genealogical roots 48-75 as innamorata, a position of vocal corporealisation © UV/UFS and diegetic confinement, to one wherein her voice assumes a position of authority over the narrative, and from one of absolute submissiveness and naïve obedience to a greatly enriched experience of her own subjectivity. 1. Introduction Tropes are rhetorical devices that consist in senses other than their literal ones. While they are useful in rendering the unfamiliar more familiar, and while understanding figurative language is part of what it means to be a member of the culture in which such language is employed, tropes easily retreat to an Potgieter & Potgieter / deconstructing disney’s divas 49 undetected state — they are “not something we are normally aware of” (Lakoff and Johnson 1980: 3) — from which enigmatic position they are able to anchor us in dominant assumptions within our society, sustaining our tacit complicity almost beyond our volition. -

Kijkwijzer (Netherlands Classification) Some Content May Not Be Appropriate for Children This Age

ACCM Kijkwijzer (Netherlands Classification) Some content may not be appropriate for children this age. Parental Content is age Kijkwijzer Australian guidance appropriate for (Netherlands Year Disney Classification recommended children this age Classification) Kijkwijzer reasons ‘Twas the Night 2001 D 6+ Violence; Fear 10 Things I Hate About You 1999 D PG 6+ Violence; Coarse language 101 Dalmatians 1996 D 6+ Violence; Fear 101 Dalmatians II: Patch’s London Adventure 2003 D All 102 Dalmatians 2000 D 6+ Violence; Fear 12 Dates of Christmas 2011 D All 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea 1954 D PG 9+ Fear A Bug’s Life 1998 D G 4 7 All A Christmas Carol 2009 D G 8 13 9+ Fear A Goofy Movie 1995 D All A Kid in King Arthur’s Court 1995 D 6+ Violence; Fear A Ring of Endless Light 2002 D 6+ Fear A Tale of Two Critters 1977 D 6+ Fear A Wrinkle in Time 2018 D PG 10 13 6+ Adventures in Babysitting 2016 D All African Cats 2011 D All Aladdin 2019 D PG 5 9 9+ Fear Aladdin 1992 D 6+ Violence; Fear Aladdin and the King of Thieves 1996 D All Aladdin: The Return of Jafar 1994 D All Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad 2014 D Day PG 5 10 All Alice in Wonderland 1951 D All Alice in Wonderland 2010 D PG 12 15 9+ Fear Alice Through the Looking Glass 2016 D PG 10 13 9+ Fear Aliens of the Deep 2005 D All Alley Cats Strike! 2000 D All Almost Angels 1962 D All America’s Heart & Soul 2004 D All Amy 1981 D 9+ Fear An Extremely Goofy Movie 2000 D All Anastasia 1997 D 6+ Violence; Fear Annie 1999 D All Ant-Man 2015 D PG 10 13 12+ Violence Ant-Man and the -

SPOKES NEWSLETTER DISTRICT 5300 * Rotary Club 794 * February 28Th, 2020 * #617 Stay Up-To-Date At

SPOKES NEWSLETTER DISTRICT 5300 * Rotary Club 794 * February 28th, 2020 * #617 Stay up-to-date at www.pasadenarotary.com This Week's Program SPEAKER: Don Hahn Story by Disney" Producer of the world-wide phenomenon The Lion King and the classic Beauty and the Beast, the first animated film to be nominated for a Best Picture Oscar® Introducer: Phil Hawkey DON HAHN is the producer of the world-wide phenomenon The Lion King and the classic Beauty and the Beast, the first animated film to be nominated for a Best Picture Oscar®. His other films include The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Maleficent starring Angelina Jolie, Tim Burton's Frankenweenie and the toon noir hit Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Don is a founding producer of the Disney nature films including Earth, Oceans, and Chimpanzee. He is also an Emmy nominated producer/director of documentaries such as Waking Sleeping Beauty now streaming on Disney+, and Freedom Writers on PBS. His latest film Howard about lyricist Howard Ashman will premiere on Disney+ this Summer. As an author, Don's books on animation, art and creativity include the bestseller "Brain Storm," the acclaimed art educational series "Drawn To Life" and his most recent book on mid-century art "Yesterday's Tomorrow." Don also serves on the Advisory Board for the Walt Disney Family Museum, and is a former trustee of PBS SoCal. Song Leader: Phil Miles Accompaniment: Ross Jutsum Inspiration: Kristina Spencer Sergeant-at-Arms: Robert Lyons Meeting Greeters: Pat Wright & Stephen McCurry Meeting Photographer: Victoria Alsabery by President Scott Vandrick by President Scott Vandrick It is always a special meeting when one of our own Pasadena Rotarians share their expertise with the Club. -

SPRING 2010 Vol. 19 No. 1

SPRING 2010 vol. 19 no. 1 Madison Liptak of Ohio, Member since 2008, celebrates the spirit of Disney Parks’ new “Give a Day, Get a Disney Day” offer by serving a senior citizen. Disney Files Magazine is published by the good people at Our world’s greatest volunteers ask for nothing in exchange for their services. Disney Vacation Club Admittedly, I’ve never been that kind of volunteer. P.O. Box 10350 Lake Buena Vista, FL 32830 Don’t get me wrong; I love serving the community as much as anyone. I just want a little something in return. Not cash, of course. That would be silly. Just a small All dates, times, events and prices token of gratitude. Like a sticker. Or a button. Or a billboard in Times Square. printed herein are subject to I once spent an entire afternoon charting and protecting sea turtle nests beneath change without notice. (Our lawyers the harmful rays of the sun at Vero Beach. I dug. I perspired. I even did math. Let’s be do a happy dance when we say that.) honest…if sea turtles avoid extinction, they’ll have me to thank. And do you remember that big parade through Indian River County in my honor? Of course you MOVING? don’t. Because it didn’t happen. Unbelievable. Update your mailing address So imagine my excitement when Disney Parks announced they were putting an online at www.dvcmember.com end to the madness and celebrating volunteers’ kindness with free tickets to one of MEMBERSHIP QUESTIONS? our Parks. (You’ll read more about the “Give a Day, Get a Disney Day” offer on pages Contact Member Services from 3-4.) Clearly, the powers that be were equally outraged by my turtle snub.