How Are Gender Roles Enabled and Constrained in Disney Music, During Classic Disney, the Disney Renaissance, and Modern Disney?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2012 Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values Allyson Scott California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Scott, Allyson, "Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values" (2012). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 391. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/391 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social and Behavioral Sciences Department Senior Capstone California State University, Monterey Bay Almost There: A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values Dr. Rebecca Bales, Capstone Advisor Dr. Gerald Shenk, Capstone Instructor Allyson Scott Spring 2012 Acknowledgments This senior capstone has been a year of research, writing, and rewriting. I would first like to thank Dr. Gerald Shenk for agreeing that my topic could be more than an excuse to watch movies for homework. Dr. Rebecca Bales has been a source of guidance and reassurance since I declared myself an SBS major. Both have been instrumental to the completion of this project, and I truly appreciate their humor, support, and advice. -

Kids Mega Pack - 224 Songs

Available from Karaoke Home Entertainment Australia and New Zealand Kids Mega Pack - 224 Songs 1 1,2 Buckle My Shoe Children's Song 2 1,2,3,4,5 Children's Song 3 7 Things Miley Cyrus 4 A Summer Song Chad And Jenny 5 A Whole New World Peabo Bryson,Regina Belle 6 Accidentally In Love Counting Crows 7 Alice Avril Lavigne 8 All For One from High School Musical 2 9 All Star Smash Mouth 10 Alphabet Song Children's Song 11 Australia Jonas Brothers 12 Bare Necessities (Bear Phil Harris Necessities) 13 Beat Of My Heart Hilary Duff 14 Beauty And The Beast Celine Dion And Peabo Bryson 15 Because You Live Jesse McCartney 16 Belle From Beauty And The Beast 17 Best Of Both Worlds Hannah Montana 18 Bet On It High School Musical 2 19 Bless The Broken Road Rascal Flatts 20 Blonde Haired Gal In A Hard Hat Bob The Builder (Wendy's Song) 21 Breaking Free Cast Of High School Musical 22 Burnin' Up Jonas Brothers 23 Bust Your Windows Glee Cast 24 Can We Fix It ? Bob The Builder 25 Can You Feel The Love Tonight Elton John 26 Chim Chim Cheree From Mary Poppins 27 Circle Of Life Elton John 28 Climb Miley Cyrus 29 Colors Of The Wind Vanessa Williams 30 Come And Get It Selena Gomez 31 Come Clean Hilary Duff 32 Crocodile Rock Bob The Builder 33 Deck The Rooftop Glee Cast 34 Defying Gravity Glee Cast 35 Ding Dong! The Witch Is Dead from Wizard Of Oz 36 Do You Want To Build A Kristen Bell feat. -

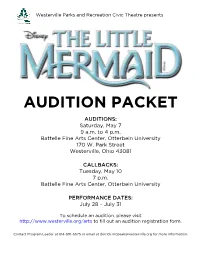

Audition Packet

Westerville Parks and Recreation Civic Theatre presents AUDITION PACKET AUDITIONS: Saturday, May 7 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Battelle Fine Arts Center, Otterbein University 170 W. Park Street Westerville, Ohio 43081 CALLBACKS: Tuesday, May 10 7 p.m. Battelle Fine Arts Center, Otterbein University PERFORMANCE DATES: July 28 – July 31 To schedule an audition, please visit http://www.westerville.org/arts to fill out an audition registration form. Contact Program Leader at 614-901-6575 or email at [email protected] for more information. AUDITION INFORMATION WHEN: Saturday, May 7, 9 a.m. - 4 p.m.; Auditions are made by appointment WHERE: Battelle Fine Arts Center, Otterbein University, 170 W Park Street, Westerville, OH 43081. HOW TO REGISTER: Please visit and click on the audition registration link. This will take you to a form where you may enter your information and preferred time of audition. You will receive a confirmation email/phone call of your audition within two business days. WHO: We welcome auditions for people of all ages! Children must be 7 years old at the time of audition. COST: For actors, singers, and dancers: $125 for children ages 7-12, $75 for adults and youth 13+. Scholarships and payment plans are available for those in need of financial assistance. HOW TO AUDITION: Groups of 10-15 performers will sing, dance, and read if needed in one hour blocks. You may audition for a specific role or for the ensemble. The dance audition will be movement based. No formal dance training is necessary. Please prepare 16 -32 bars of any musical theatre song (enough to cover one verse and one chorus). -

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis

arts Article Cultural “Authenticity” as a Conflict-Ridden Hypotext: Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis Zhuoyi Wang Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, Hamilton College, Clinton, NY 13323, USA; [email protected] Received: 6 June 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 10 July 2020 Abstract: Disney’s Mulan (1998) has generated much scholarly interest in comparing the film with its hypotext: the Chinese legend of Mulan. While this comparison has produced meaningful criticism of the Orientalism inherent in Disney’s cultural appropriation, it often ironically perpetuates the Orientalist paradigm by reducing the legend into a unified, static entity of the “authentic” Chinese “original”. This paper argues that the Chinese hypotext is an accumulation of dramatically conflicting representations of Mulan with no clear point of origin. It analyzes the Republican-era film adaptation Mulan Joins the Army (1939) as a cultural palimpsest revealing attributes associated with different stages of the legendary figure’s millennium-long intertextual metamorphosis, including a possibly nomadic woman warrior outside China proper, a Confucian role model of loyalty and filial piety, a Sinitic deity in the Sino-Barbarian dichotomy, a focus of male sexual fantasy, a Neo-Confucian exemplar of chastity, and modern models for women established for antagonistic political agendas. Similar to the previous layers of adaptation constituting the hypotext, Disney’s Mulan is simply another hypertext continuing Mulan’s metamorphosis, and it by no means contains the most dramatic intertextual change. Productive criticism of Orientalist cultural appropriations, therefore, should move beyond the dichotomy of the static East versus the change-making West, taking full account of the immense hybridity and fluidity pulsing beneath the fallacy of a monolithic cultural “authenticity”. -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

2610 Canada Blvd

2610 Canada Blvd. Glendale, CA 91208 FOR SALE CAROLINE GIM Expert Real Estate & Investment 562 861 4311 Direct [email protected] STEVE GIM Vice President NAI Capital Commercial Inc. 949.468.2333 Direct 562.822.0420 Mobile [email protected] CA DRE #01400546 Opportunity Overview: DAVID KNOWLTON, SIOR, CCIM NAI Capital Commercial, Inc and Expert Real Estate are proud to present a rare opportunity to own a beautiful Executive Vice President 1940’s Residential Duplex in desirable Glendale, CA. On the market for the first time in over 40 years, this NAI Capital Commercial, Inc. charming property features two spacious ; 2+2 and 2+1 units on 0.29 acres. The asset features original 949.468.2307 Direct hardwood floors and two fireplaces in each unit. In addition, there is plenty of onsite parking with a four‐car 949.887.7872 Mobile detached garage. Possible ADU garage conversion or completely redevelop into 4 units with the current R‐3050 Land Zoning Classification. Buyer to verify all information as part of their Due Diligence. [email protected] CA DRE #00893394 No warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy of the information contained herein. This information is submitted subject to errors, omissions, change of price, rental or other conditions, withdrawal without notice, and is subject to any special listing conditions imposed by our principals. Cooperating brokers, buyers, tenants and other parties who receive this document should not rely on it, but should use it as a starting point of analysis, and should independently confirm the accuracy of the information contained herein through a due diligence review of the books, records, files and documents that constitute reliable sources of the information described herein. -

Historical Inaccuracies and a False Sense of Feminism in Disney’S Pocahontas

Cyrus 1 Lydia A. Cyrus Dr. Squire ENG 440 Film Analysis Revision Fabricated History and False Feminism: Historical Inaccuracies and a False Sense of Feminism in Disney’s Pocahontas In 1995, following the hugely financial success of The Lion King, which earned Disney close to one billion is revenue, Walt Disney Studios was slated to release a slightly more experimental story (The Lion King). Previously, many of the feature- length films had been based on fairy tales and other fictional stories and characters. However, over a Thanksgiving dinner in 1990 director Mike Gabriel began thinking about the story of Pocahontas (Rebello 15). As the legend goes, Pocahontas was the daughter of a highly respected chief and saved the life of an English settler, John Smith, when her father sought out to kill him. Gabriel began setting to work to create the stage for Disney’s first film featuring historical events and names and hoped to create a strong female lead in Pocahontas. The film would be the thirty-third feature length film from the studio and the first to feature a woman of color in the lead. The project had a lot of pressure to be a financial success after the booming success of The Lion King but also had the added pressure from director Gabriel to get the story right (Rebello 15). The film centers on Pocahontas, the daughter of the powerful Indian chief, Powhatan. When settlers from the Virginia Company arrive their leader John Smith sees it as an adventure and soon he finds himself in the wild and comes across Pocahontas. -

The Piano Duet Play-Along Series Gives You the • I Dreamed a Dream • in My Life • on My Own • Stars

1. Piano Favorites 13. Movie Hits 9 great duets: Candle in the Wind • Chopsticks • Don’t 8 film favorites: Theme from E.T. (The Extra-Terrestrial) Know Why • Edelweiss • Goodbye Yellow Brick Road • • Forrest Gump – Main Title (Feather Theme) • The Heart and Soul • Let It Be • Linus and Lucy • Your Song. Godfather (Love Theme) • The John Dunbar Theme • Moon 00290546 Book/CD Pack ............................$14.95 River • Romeo and Juliet (Love Theme) • Theme from Schindler’s List • Somewhere, My Love. 2. Movie Favorites 00290560 Book/CD Pack ...........................$14.95 8 classics: Chariots of Fire • The Entertainer • Theme from Jurassic Park • My Father’s Favorite • My Heart Will Go 14. Les Misérables On (Love Theme from Titanic) • Somewhere in Time • 8 great songs from the musical: Bring Him Home • Castle on Somewhere, My Love • Star Trek® the Motion Picture. a Cloud • Do You Hear the People Sing? • A Heart Full of Love The Piano Duet Play-Along series gives you the • I Dreamed a Dream • In My Life • On My Own • Stars. flexibility to rehearse or perform piano duets 00290547 Book/CD Pack ............................$14.95 00290561 Book/CD Pack ...........................$16.95 anytime, anywhere! Play these delightful tunes 3. Broadway for Two 10 songs from the stage: Any Dream Will Do • Blue Skies 15. God Bless America® & Other with a partner, or use the accompanying CDs • Cabaret • Climb Ev’ry Mountain • If I Loved You • Okla- to play along with either the Secondo or Primo Songs for a Better Nation homa • Ol’ Man River • On My Own • There’s No Business 8 patriotic duets: America, the Beautiful • Anchors part on your own. -

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs 10.11.82 Scene 1

SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS 10.11.82 SCENE 1 : In the palace (lights on to WickeD Queen holDing mirror up anD gazing into it) WICKED QUEEN: (to mirror) Mirror, mirror in my hanD, Who’s the fairiest in the lanD……? MIRROR (VOICE): Queen, THOU art the fairiest in this hall, But Snow White's fairer than us all.….. WICKED QUEEN: (to mirror) For years you've tolD me I'm lovely anD fair, Competition is something I simply can't bear…… It's perfectly clear Snow White must go, But how to do it? - I think I know…… (calls to servant offstage) WICKED QUEEN: Bring me someone who knows the bush well, AnD to him my Devious plan I will tell...... (enter scout) WICKED QUEEN: Take Snow White into the bush, Take her to Govett's and give her a push…… (cackles) SCOUT: But she's such a fair child, So pure and young......! WICKED QUEEN : Do as I say and hold your tongue......! (both exit separately) SCENE 2 : In the bush near Govett's (typical Australian bush sounDs - kookooburras, chainsaws, 4WD' s, cruDe bushwalkers … enter Snow White accompanieD by scout) SCOUT: Do you aDmire the view my Dear? There's a pleasant picnic spot near here...... So here we are, a pleasant twosome, But I have a job that's really quite gruesome…… (aside) I'll sit down here and give her a drink, Before I shove her over the brink...... SNOW WHITE: We've walkeD all morning, anD my feet are so sore, I cant go on - I've blisters galore..... -

Poor Unfortunate Souls)

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 SYNOPSIS 2 CASTING 4 MUSIC DIRECTION 8 DIRECTING TIPS 17 DESIGN 20 BEYOND THE STAGE 35 RESOURCES 44 CREDITS 48 Betcha on land They understand Bet they don’t reprimand their daughters Bright young women Sick of swimmin’ Ready to stand — “Part of Your World,” lyrics by Howard Ashman INTRODUCTION hether you first came toThe Little Mermaid by searching for his place in the world. As Ariel and Eric way of the original Hans Christian Andersen learn to make decisions for themselves, King Triton tale, the classic Disney animated film, or the stage and Grimsby learn the parental lesson of letting go. musical adaptation, the story resonates with the same emotional power. Strip the tale of its fantastical The stage adaptation of The Little Mermaid – with Betcha on land elements – mermaids and sea witches and talking music by Alan Menken, lyrics by Howard Ashman crabs – and what’s left is the simple story of a young and Glenn Slater, and book by Doug Wright – retains They understand woman struggling to come into her own. the most beloved songs and moments from the original film while deepening the core relationships There’s a little bit of Ariel in all of us: headstrong, and themes, adding in layers, textures, and songs Bet they don’t reprimand their daughters independent, insatiably curious, and longing to know to form an even more moving and relevant story. the world in all of its glory, mystery, and diversity. A This stage musical presents endless opportunities Bright young women young woman who passionately pursues her dream, for creative design – from costuming the merfolk, to Ariel makes decisions that have serious consequences, creating distinct underwater and on-land worlds, to all of which she faces with bravery and dignity.