Topic 3. Diet Digestibilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Article Chemical, Bioactive, and Antioxidant Potential of Twenty Wild Culinary Mushroom Species

Hindawi Publishing Corporation BioMed Research International Volume 2015, Article ID 346508, 12 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/346508 Research Article Chemical, Bioactive, and Antioxidant Potential of Twenty Wild Culinary Mushroom Species S. K. Sharma1 and N. Gautam2 1 Department of Plant Pathology, CSK, Himachal Pradesh Agriculture University, Palampur 176 062, India 2Centre for Environmental Science and Technology, School of Environment and Earth Sciences, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda 151 001, India Correspondence should be addressed to N. Gautam; [email protected] Received 8 May 2015; Accepted 11 June 2015 Academic Editor: Miroslav Pohanka Copyright © 2015 S. K. Sharma and N. Gautam. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The chemical, bioactive, and antioxidant potential of twenty wild culinary mushroom species being consumed by the peopleof northern Himalayan regions has been evaluated for the first time in the present study. Nutrients analyzed include protein, crude fat, fibres, carbohydrates, and monosaccharides. Besides, preliminary study on the detection of toxic compounds was done on these species. Bioactive compounds evaluated are fatty acids, amino acids, tocopherol content, carotenoids (-carotene, lycopene), flavonoids, ascorbic acid, and anthocyanidins. Fruitbodies extract of all the species was tested for different types of antioxidant assays. Although differences were observed in the net values of individual species all the species were found to be rich in protein, and carbohydrates and low in fat. Glucose was found to be the major monosaccharide. Predominance of UFA (65–70%) over SFA (30–35%) was observed in all the species with considerable amounts of other bioactive compounds. -

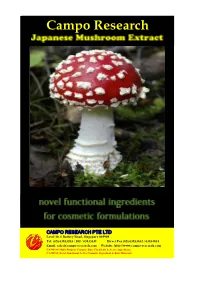

Japanese Mushroom Extracts 2

Campo Research CAMPO RESEARCH PTE LTD Level 30, 6 Battery Road, Singapore 049909 Tel: (65) 63833203 / 202 / 63833631 Direct Fax (65) 63833632 / 63834034 Email: [email protected] Website: http///www.campo-research.com CAMPO® Multi-Purpose Cosmetic Base Chemicals & Active Ingredients CAMPO® Novel Functional Active Cosmetic Ingredient & Raw Materials Campo Japanese Mushroom Extracts 2 JAPANESE MUSHROOM EXTRACTS Index Introduction Glycolic Extracts (1,3-butylene glycol) Eburiko Fomistopsis officinalis Kawarate Coriolus versicolor Magojakushi Ganoderma neo-japanicum Mannentake Ganoderma lucidum Matsutake Tricholoma matsutake Raigankin Polyporus mylittae Semitake Cordyceps sabolifera Tsugasaromoshikake Fomistopsis pinicola Tsuriganedake Fomes fometarius Aqueous Extracts Matsutake Tricholoma matsutake IMPORTANT NOTICE Specifications may change without prior notice. Information contained in this technical literature is believed to be accurate and is offered in good faith for the benefit of the customer. The company, however, cannot assume any liability or risk involved in the use of its natural products or their derivatives, since the conditions of use are beyond our control. Statements concerning the possible use are not intended as recommendations to use our products in the infringement of any patent. We make no warranty of any kind; expressed or implied, other than that the material conforms to the applicable standard specifications. Ask about our Herbal Natural Products Chemistry Consultancy Services – Product Registration EEC/UK New Drug Development (NDA-US); Quasi-Drug Topicals (MOHW_Japan); Development of Standards, Analysis & Profiles of Phytochemicals; Literature searches, Cultivation of Medicinal Plants, Clinical-Trials, Development of new uses for Phytochemicals and Extracts; Contract Research and Development Work in Natural Products for Novel Drugs, New Cosmetic Active Ingredients for Active Topica/OTC Cosmetic with functionality and Consumer-perceivable immediate-results, New Food Ingredients for Nutraceuticals & Functional Foods. -

Economically Important Plants Arranged Systematically James P

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 1-2017 Economically Important Plants Arranged Systematically James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "Economically Important Plants Arranged Systematically" (2017). Botanical Studies. 48. http://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/48 This Economic Botany - Ethnobotany is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ECONOMICALLY IMPORTANT PLANTS ARRANGED SYSTEMATICALLY Compiled by James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State University Arcata, California 30 January 2017 This list began in 1970 as a handout in the Plants and Civilization course that I taught at HSU. It was an updating and expansion of one prepared by Albert F. Hill in his 1952 textbook Economic Botany... and it simply got out of hand. I also thought it would be useful to add a brief description of how the plant is used and what part yields the product. There are a number of more or less encyclopedic references on this subject. The number of plants and the details of their uses is simply overwhelming. In the list below, I have attempted to focus on those plants that are of direct economic importance to us. -

April 2014 Volume 75 No

New England Society of American Foresters News Quarterly APRIL 2014 VOLUME 75 NO. 2 Massachusetts Resumes Timber Harvesting on State Lands Massachusetts State Lands Management Update – Provided by William N. Hill, CF, Management Forestry Program Supervisor, MA Department of Conservation and Recreation As most are aware the Massachusetts State Lands Forest Management Pro- gram recently went through a significant review of forestry practices which re- sulted in changes to landscape zoning, public outreach policy and approaches to silviculture. After a three year hiatus from active forest management the Bureau of Forestry successfully sold 5 of 7 timber sales offered last fall and this winter. The silviculture of the projects ranged from irregular shelterwood and uneven aged management in northern hardwoods and mixed hardwoods to ecological restoration on pitch pine/scrub oak sites through the removal of red pine plantations. The Bureau has proposed an additional 5 projects which will result in timber sale offerings early this summer. The Water Supply Pro- tection Division is also on the cusp of resuming their forest management pro- gram with timber sale offerings in March. Inside this issue: Special points of interest: ♦ 2014 NESAF Award Recipients Science Theme 8 State News 19 CFE Update 27 1 Members Serving You In 2014 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OFFICERS Chair: Jim Harding Green Mountain College One Brennan Circle Poultney, VT 05764 802-287-8328 [email protected] Vice-Chair: Vacant Immediate Past Chair: Edward O’Leary, 1808 S Albany Rd, Craftsbury Common, VT 05827, (O) 802-793-3712 (F) 802-244-1481 [email protected] Secretary: Emma Schultz Clayton Lake, ME (c) 651-319-2008 [email protected] Treasurer: Russell Reay, 97 Stewart Lane, Cuttingsville, VT, 05738 (O) 802-492-3323 [email protected] EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE REPRESENTATIVES Canada: Donald W. -

Amanita Muscaria (“Fly Agaric”)

WILD MUSHROOMS An Introductory Presentation by Pam McElroy and Anna Russo Lincoln County Mycological Society FIELD GUIDES • Mushrooms Demystified by David Arora • All That the Rain Promises, and More by David Arora • Field Guide to Mushrooms from National Audubon Society • Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest by Steven Trudell & Joe Ammirati Mushroom Identification Traits • Gills/Pores/Teeth: What sort of spore- producing structures do you see? How are they attached? • Stalk description: Note the size, shape, color of stalk, and whether it is solid or hollow. • Spore color: Extremely important for ID. Identification Characteristics • Bruising when touched: Does the mushroom change color or bleed any liquid when it is sliced in half or grasped firmly? • Habitat: Anything about the surrounding area, including trees, temperature, soil, moisture. • Time of year: certain mushrooms fruit during certain times of the year • Cap description: Like the stalk, note all physical characteristics of the cap. • Smell and taste: Great amount of information The Good Guys……….. Edible, delicious, delectable…….what’s not to love? The bad guys………. • Like the little girl with the curl, when mushrooms are good, they are very, very good……….and when they are bad, they are dreadful! • There are some DEADLY mushrooms….and you can’t tell which ones unless you educate yourself. Let’s take a look at some of the “bad boys” of the mushroom world. • Before you even consider eating a wild mushroom that you have picked, you MUST know the poisonous ones. • In mycological circles, -

Ethnomycological Investigation in Serbia: Astonishing Realm of Mycomedicines and Mycofood

Journal of Fungi Article Ethnomycological Investigation in Serbia: Astonishing Realm of Mycomedicines and Mycofood Jelena Živkovi´c 1 , Marija Ivanov 2 , Dejan Stojkovi´c 2,* and Jasmina Glamoˇclija 2 1 Institute for Medicinal Plants Research “Dr Josif Pancic”, Tadeuša Koš´cuška1, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] 2 Department of Plant Physiology, Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stankovi´c”—NationalInstitute of Republic of Serbia, University of Belgrade, Bulevar despota Stefana 142, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (J.G.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +381-112078419 Abstract: This study aims to fill the gaps in ethnomycological knowledge in Serbia by identifying various fungal species that have been used due to their medicinal or nutritional properties. Eth- nomycological information was gathered using semi-structured interviews with participants from different mycological associations in Serbia. A total of 62 participants were involved in this study. Eighty-five species belonging to 28 families were identified. All of the reported fungal species were pointed out as edible, and only 15 of them were declared as medicinal. The family Boletaceae was represented by the highest number of species, followed by Russulaceae, Agaricaceae and Polypo- raceae. We also performed detailed analysis of the literature in order to provide scientific evidence for the recorded medicinal use of fungi in Serbia. The male participants reported a higher level of ethnomycological knowledge compared to women, whereas the highest number of used fungi species was mentioned by participants within the age group of 61–80 years. In addition to preserving Citation: Živkovi´c,J.; Ivanov, M.; ethnomycological knowledge in Serbia, this study can present a good starting point for further Stojkovi´c,D.; Glamoˇclija,J. -

Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Wild Tunisian Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms

International Journal of Medicinal Plants and Natural Products (IJMPNP) Volume 5, Issue 2, 2019, PP 28-36 ISSN 2454-7999 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-7999.0502004 www.arcjournals.org Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Wild Tunisian Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms Rim Ben Mansour*, Sarra Dakhlaoui, Riadh Ksouri, Wided Megdiche-Ksouri. Laboratory ofAromatic and Medicinal Plants, Center of Biotechnology, Technopark of Borj-Cedria (CBBC), BP 901, 2050 Hammam-Lif, Tunisia. *Corresponding Author: Rim Ben Mansour, Laboratory ofAromatic and Medicinal Plants, Center of Biotechnology, Technopark of Borj-Cedria (CBBC), BP 901, 2050 Hammam-Lif, Tunisia. Abstract: Wild medicinal mushrooms have been considered as therapeutic agents since long in Asian countries, but their use in Tunisia has been slightly increased only since the last few years. This study is, to our knowledge, the first to investigate the richness of four wild Tunisian edible and medicinal species of basidiomycetes (Tricholoma terreum, Tricholoma equestre, Ganoderma lucidum and Agaricus campestris) on phenolics, fatty acids and to evaluate their antioxidant properties via 5 in vitro tests. Significant differences were observed in phenolic contents and antioxidant capacities between species. G. Lucidum extract exhibited the highest phenolic and flavonoid contents (18.7 mg EAG/g DW and 5.3 mg CE/g DW) related to the important total antioxidant capacity (5.4 mg EAG/g DW), DPPH (IC50=0.14 mg/mL), ABTS (IC50=0.98 mg/mL) and β-carotene bleaching tests (IC50=0.26 mg/mL), respectively. Fatty acids profiles of these species were carried out by chromatography. High levels of unsaturated fatty acids (79.5-84.2 %) were observed in all species, which gives them an important nutritional value. -

Hericium Ramosum - Comb’S Tooth Fungi

2005 No. 4 Hericium ramosum - comb’s tooth fungi This year we have been featuring the finalists of the “Pick a Wild Mushroom, Alberta!” project. Although the winner was the Leccinum boreale all the finalists are excellent edibles which show the variety of mushroom shapes common in Alberta. If all you learned were these three finalists and the ever popular morel you would have a useable harvest every year. The taste and medicinal qualities of each is very different so you not only have variety in shape and location but in taste and value as well. If you learn about various edible species and hunt for harvest you will become a mycophagist. Although you won’t need four years of university to get this designation, you will find that over the lifetime of learning about and harvesting mushroom you will put in more time than the average Hericium ramosum is a delicately flavoured fungi that is easily recognized and has medicinal university student and probably properties as well. Photo courtesy: Loretta Puckrin. enjoy it much more. edible as well. With their white moments of rapt viewing before the Although often shy and hard fruiting bodies against the dark picking begins. People to find, this delicious fungus family trunks of trees, this fungus is knowledgeable in the medicinal is a favourite of new mushroom easily spotted and often produces pickers as all the ‘look alikes’ are (The Hericium ...continued on page 3) FEATURE PRESIDENT’S PAST EVENTS NAMA FORAY & UPCOMING MUSHROOM MESSAGE Lambert Creek ... pg 5 CONFERENCE EVENTS The Hericium It has been a .. -

Biodiversity, Distribution and Morphological Characterization of Mushrooms in Mangrove Forest Regions of Bangladesh

BIODIVERSITY, DISTRIBUTION AND MORPHOLOGICAL CHARACTERIZATION OF MUSHROOMS IN MANGROVE FOREST REGIONS OF BANGLADESH KALLOL DAS DEPARTMENT OF PLANT PATHOLOGY FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE SHER-E-BANGLA AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY DHAKA-1207 JUNE, 2015 BIODIVERSITY, DISTRIBUTION AND MORPHOLOGICAL CHARACTERIZATION OF MUSHROOMS IN MANGROVE FOREST REGIONS OF BANGLADESH BY KALLOL DAS Registration No. 15-06883 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Agriculture, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka, In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN PLANT PATHOLOGY SEMESTER: JANUARY - JUNE, 2015 APPROVED BY : ---------------------------------- ----------------------------------- ( Mrs. Nasim Akhtar ) (Dr. F. M. Aminuzzaman) Professor Professor Department of Plant Pathology Department of Plant Pathology Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University Supervisor Co-Supervisor ----------------------------------------- (Dr. Md. Belal Hossain) Chairman Examination Committee Department of Plant Pathology Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka Department of Plant Pathology Fax: +88029112649 Sher- e - Bangla Agricultural University Web site: www.sau.edu.bd Dhaka- 1207 , Bangladesh CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, “BIODIVERSITY, DISTRIBUTION AND MORPHOLOGICAL CHARACTERIZATION OF MUSHROOMS IN MANGROVE FOREST REGIONS OF BANGLADESH’’ submitted to the Department of Plant Pathology, Faculty of Agriculture, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka, in the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE (M. S.) IN PLANT PATHOLOGY, embodies the result of a piece of bonafide research work carried out by KALLOL DAS bearing Registration No. 15-06883 under my supervision and guidance. No part of the thesis has been submitted for any other degree or diploma. I further certify that such help or source of information, as has been availed of during the course of this investigation has duly been acknowledged. -

Harvesting of Non-Wood Forest Products

JOINT FAO/ECE/ILO COMM TTEE ON FOREST TECHNOLOGY, MANAGEMENT AND TRAINING SEMINAR PROCEEDINGS HARVESTING OF NON-WOOD FOREST PRODUCTS Menemenizmir, Turkey 2-8 October 2000 0 0 0 ' 0 D DD. HARVESTING OF NON-WOOD FOREST PRODUCTS Menemenlzmir, Turkey 2-8 October 2000 Hosted by the Ministry of Forestry in Turkey in the International Agro-Hydrology Research and Training Center INTERNATIONAL LABOUR ORGANIZATION UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2003 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination ofmaterial in this information product for educational or other non-commercialpurposes are authorized without any prior written permission from thecopyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction ofmaterial in this information product for resale or other commercialpurposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders.Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Chief, PublishingManagement Service, Information Division, FAO, Viale delle Terme diCaracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to [email protected] © FAO 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS / TABLE DES MATIÈRES Page Foreword / Préface vii Report of the seminar Rapport du séminaire I Report of the seminar (in Russian) 21 Papers contributed to the seminar / Documents présentés au séminaire Medicinal and aromatic commercial native plants in the Eastern Black Sea region of Turkey / Plantes médicinales et aromatiques d'intérêt commercial indigènes de la région orientale de la mer Noire de la Turquie - (Messrs. -

FOOD PLANTS of the NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS by ELIAS YANOVSKY, Chemist, Carbohydrate Resea'rch Division, Bureau of Chemistry and Soils

r I UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Miscellaneous Publication No. 237 Washington, D. C. July 1936 FOOD PLANTS OF THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS By KLIAS YANOYSKY Chemist Carbohydrate Research Division, Bureau of Chemistry and Soils Foe sale by the Superintendent of Dosnenia, Washington. D. C. Price 10 centS UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATION No. 237 WASHINGTON, D. C. JULY 1936 FOOD PLANTS OF THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS By ELIAS YANOVSKY, chemist, Carbohydrate Resea'rch Division, Bureau of Chemistry and Soils CONTENTS Page Page Foreword 1 Literature cited 65 Introduction I Index 69 Plants 2 FOREWORD This publication is a summary of the records of food plants used by the Indians of the United States and Canada which have appeared in ethnobotanical publications during a period of nearly 80 years.This compilation, for which all accessible literature has been searched, was drawn up as a preliminary to work by the Bureau of Chemistry and Soils on the chemical constituents and food value of native North American plants.In a compilation of this sort, in which it is im- possible to authenticate most of the botanical identifications because of the unavailability of the specimens on which they were based, occa- sional errors are unavoidable.All the botanical names given have been reviewed in the light of our present knowledge of plant distribu- tion, however, and it is believed that obvious errors of identification have been eliminated. The list finds its justification as a convenient summary of the extensive literature and is to be used subject to con- firmation and correction.In every instance brief references are made to the original authorities for the information cited. -

Mushroom Hunting and Consumption in Twenty-First Century Post-Industrial Sweden Ingvar Svanberg* and Hanna Lindh

Svanberg and Lindh Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2019) 15:42 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-019-0318-z RESEARCH Open Access Mushroom hunting and consumption in twenty-first century post-industrial Sweden Ingvar Svanberg* and Hanna Lindh Abstract Background: The pre-industrial diet of the Swedish peasantry did not include mushrooms. In the 1830s, some academic mycologists started information campaigns to teach people about edible mushrooms. This propaganda met with sturdy resistance from rural people. Even at the beginning of the last century, mushrooms were still only being occasionally eaten, and mostly by the gentry. During the twentieth century, the Swedish urban middle class accepted mushrooms as food and were closely followed by the working-class people. A few individuals became connoisseurs, but most people limited themselves to one or two taxa. The chanterelle, Cantharellus cibarius Fr., was (and still is) the most popular species. It was easy to recognize, and if it was a good mushroom season and the mushroomer was industrious, considerable amounts could be harvested and preserved or, from the late 1950s, put in the freezer. The aim of this study is to review the historical background of the changes in attitude towards edible mushrooms and to record today’s thriving interest in mushrooming in Sweden. Methods: A questionnaire was sent in October and November 2017 to record contemporary interest in and consumption of mushrooms in Sweden. In total, 100 questionnaires were returned. The qualitative analysis includes data extracted from participant and non-participant observations, including observations on activities related to mushroom foraging posted on social media platforms, revealed through open-ended interviews and in written sources.