Practical Recolonisation? John Borrows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marie Laing M.A. Thesis

Conversations with Young Two-Spirit, Trans and Queer Indigenous People About the Term Two-Spirit by Marie Laing A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Social Justice Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Marie Laing 2018 Conversations with Young Two-Spirit, Trans and Queer Indigenous People About the Term Two-Spirit Marie Laing Master of Arts Department of Social Justice Education University of Toronto 2018 Abstract Since the coining of the term in 1990, two-spirit has been used with increasing frequency in reference to Indigenous LGBTQ people; however, there is rarely explicit discussion of to whom the term two-spirit refers. The word is often simultaneously used as both an umbrella term for all Indigenous people with complex genders or sexualities, and with the specific, literal understanding that two-spirit means someone who has two spirits. This thesis discusses findings from a series of qualitative interviews with young trans, queer and two-spirit Indigenous people living in Toronto. Exploring the ways in which participants understand the term two-spirit to be a meaningful and complex signifier for a range of ways of being in the world, this paper does not seek to define the term two-spirit; rather, following the direction of research participants, the thesis instead seeks to trouble the idea that articulating a definition of two-spirit is a worthwhile undertaking. ii Acknowledgments There are many people without whom I would not have been able to complete this research. Thank you to my supervisor, Dr. -

From Sovereignty to Self-Determination: Emergence of Collective Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Natural Resources Management

From Sovereignty to Self-Determination: Emergence of Collective Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Natural Resources Management SHAWKAT ALAM* AND ABDULLAH AL FARUQUE** ABSTRACT The principle of permanent sovereignty over natural resources (ªPSNRº) is now widely recognized as an important principle of international law. It derives its meaning from the instrument that is widely regarded as establish- ing its status in international lawÐthe United Nations (ªU.N.º) General Assembly Resolution 1803 (XVII) of 14 December 1962, ªPermanent Sovereignty over Natural Resourcesº (ªthe 1962 Declarationº). The pream- ble to the 1962 Declaration de®nes the principle, asserting that any measure in respect of PSNR ªmust be based on the recognition of the inalienable right of all States freely to dispose of their natural wealth and resources in accordance with their national interests, and on respect for the economic in- dependence of States.º However, since its inception in the second half of the twentieth century, PSNR has been increasingly considered as a principle ex- pressive of the right of peoples, not just states. Indeed, there is a discernible trend of extending the principle of PSNR to the interests of indigenous peo- ples so that they can exercise control over their traditional lands and territo- ries. Indigenous peoples are receiving increasing attention in international instruments. States are now under an obligation to exercise permanent sov- ereignty on behalf of their indigenous communities, as well as for the bene®t of their citizens as a whole. The exercise of three particular rights of indige- nous peoplesÐthe right to self-determination, the right to traditionally own land and resources, and the right to prior informed consentÐcan help indig- enous peoples exercise their right to permanent sovereignty within the nation state. -

Trip to Australia March 4 to April 3, 2014

TRIP TO AUSTRALIA MARCH 4 TO APRIL 3, 2014 We timed this trip so that we'd be in Australia at the beginning of their fall season, reasoning that had we come two months earlier we would have experienced some of the most brutal summer weather that the continent had ever known. Temperatures over 40°C (104°F) were common in the cities that we planned to visit: Sydney (in New South Wales), Melbourne* (in Victoria), and Adelaide (in South Australia); and _____________________________________________________________ *Melbourne, for example, had a high of 47°C (117°F) on January 21; and several cities in the interior regions of NSW, Vic, and SA had temperatures of about 50°C (122°F) during Decem ber-January. _______________________________________________________________ there were dangerous brush fires not far from populated areas. As it turned out, we were quite fortunate: typical daily highs were around 25°C (although Adelaide soared to 33°C several days after we left it) and there were only a couple of days of rain. In m y earlier travelogs, I paid tribute to m y wife for her brilliant planning of our journey. So it was this time as well. In the months leading up to our departure, we (i.e., Lee) did yeoman (yeowoman? yo, woman?) work in these areas: (1) deciding which regions of Australia to visit; (2) scouring web sites, in consultation with the travel agency Southern Crossings, for suitable lodging; (3) negotiating with Southern Crossings (with the assistance of Stefan Bisciglia of Specialty Cruise and Villas, a fam ily-run travel agency in Gig Harbor) concerning city and country tours, tickets to events, advice on sights, etc.; and (4) reading several web sites and travel books. -

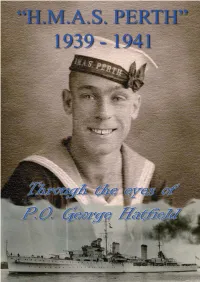

37845R CS3 Book Hatfield's Diaries.Indd

“H.M.A.S. PERTH” 1939 -1941 From the diaries of P.O. George Hatfield Published in Sydney Australia in 2009 Publishing layout and Cover Design by George Hatfield Jnr. Printed by Springwood Printing Co. Faulconbridge NSW 2776 1 2 Foreword Of all the ships that have flown the ensign of the Royal Australian Navy, there has never been one quite like the first HMAS Perth, a cruiser of the Second World War. In her short life of just less than three years as an Australian warship she sailed all the world’s great oceans, from the icy wastes of the North Atlantic to the steamy heat of the Indian Ocean and the far blue horizons of the Pacific. She survived a hurricane in the Caribbean and months of Italian and German bombing in the Mediterranean. One bomb hit her and nearly sank her. She fought the Italians at the Battle of Matapan in March, 1941, which was the last great fleet action of the British Royal Navy, and she was present in June that year off Syria when the three Australian services - Army, RAN and RAAF - fought together for the first time. Eventually, she was sunk in a heroic battle against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Java Sea off Indonesia in 1942. Fast and powerful and modern for her times, Perth was a light cruiser of some 7,000 tonnes, with a main armament of eight 6- inch guns, and a top speed of about 34 knots. She had a crew of about 650 men, give or take, most of them young men in their twenties. -

EDO Annual Report 2019/20

EDO Impact Report 2019/2020 1 Annual Report 2019/2020 Acknowledgement of Country The Environmental Defenders Office recognises the traditional owners and custodians of the land, seas and rivers of Australia. We pay our respects to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander elders past and present, and aspire to learn from traditional knowledge and customs so that, together, we can protect our environment and cultural heritage through law. EDO Impact Report 2019/2020 3 Contents A New Era for EDO 06 Governance 08 Safe Climate 12 First Nations Engagement and Cultural Heritage 20 Biodiversity 24 Healthy Communities 34 Water 38 International Program 42 Our People 46 Acknowledgements 53 Financial Report 60 Our Vision Our vision is a world where nature thrives; where robust laws protect our plants, animals and climate; and where communities across Australia are empowered to fight for environmental justice. Published on 11th December 2020 A Word from the Chair I wish to start by paying my 2. Building organisational and leadership respects to First Nations capacity: Coming together gave us an peoples and, in particular, opportunity to build on the strengths of elders past, present, and individuals within existing offices, grow emerging. I specifically wish to organisational capacity - particularly in the acknowledge the Yuin people smaller regional offices - provide career path and their country, which is opportunities for existing staff and attract where I live. exceptionally talented individuals to new roles. As you will read about in more detail in the What an extraordinary 12 months it has been! report, this has been a key achievement of our After four years of preparation, and on the back first 12 months. -

Annual Report 2019/2020 Acknowledgement of Country

EDO Impact Report 2019/2020 1 Annual Report 2019/2020 Acknowledgement of Country The Environmental Defenders Office recognises the traditional owners and custodians of the land, seas and rivers of Australia. We pay our respects to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander elders past and present, and aspire to learn from traditional knowledge and customs so that, together, we can protect our environment and cultural heritage through law. EDO Impact Report 2019/2020 3 Contents A New Era for EDO 06 Governance 08 Safe Climate 12 First Nations Engagement and Cultural Heritage 20 Biodiversity 24 Healthy Communities 34 Water 38 International Program 42 Our People 46 Acknowledgements 53 Financial Report 60 Our Vision Our vision is a world where nature thrives; where robust laws protect our plants, animals and climate; and where communities across Australia are empowered to fight for environmental justice. Published on 11th December 2020 A Word from the Chair I wish to start by paying my 2. Building organisational and leadership respects to First Nations capacity: Coming together gave us an peoples and, in particular, opportunity to build on the strengths of elders past, present, and individuals within existing offices, grow emerging. I specifically wish to organisational capacity - particularly in the acknowledge the Yuin people smaller regional offices - provide career path and their country, which is opportunities for existing staff and attract where I live. exceptionally talented individuals to new roles. As you will read about in more detail in the What an extraordinary 12 months it has been! report, this has been a key achievement of our After four years of preparation, and on the back first 12 months. -

State of the World's Indigenous Peoples

5th Volume State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples Photo: Fabian Amaru Muenala Fabian Photo: Rights to Lands, Territories and Resources Acknowledgements The preparation of the State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples: Rights to Lands, Territories and Resources has been a collaborative effort. The Indigenous Peoples and Development Branch/ Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues within the Division for Inclusive Social Development of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat oversaw the preparation of the publication. The thematic chapters were written by Mattias Åhrén, Cathal Doyle, Jérémie Gilbert, Naomi Lanoi Leleto, and Prabindra Shakya. Special acknowledge- ment also goes to the editor, Terri Lore, as well as the United Nations Graphic Design Unit of the Department of Global Communications. ST/ESA/375 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Division for Inclusive Social Development Indigenous Peoples and Development Branch/ Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues 5TH Volume Rights to Lands, Territories and Resources United Nations New York, 2021 Department of Economic and Social Affairs The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environ- mental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. -

Indigenous Creativity and the Public Domain – Terra Nullius Revisited?1

Indigenous Creativity and the Public Domain – Terra Nullius Revisited?1 Mattias Åhrén 1 Introduction This chapter attempts to draw an analogy between the terra nullius doctrine and its efffects on indigenous peoples’ capacity to control their traditional ter- ritories, and the notion of a so-called public domain and its impact on who can access indigenous peoples’ respective cultural heritages. To what extent indigenous peoples2 have established rights over land through inhabitation and traditional use has been a concern of international law since its inception. It is generally held that the roots of the contemporary international legal system can be traced back to the second half of the 1600s. The international normative order that then gradually emerged did not only support the colonization of indigenous territories. It was indeed developed largely for facilitating European imperialism. Section 2 explains how the Euro- pean states invoked the principle of state sovereignty to proclaim the so-called terra nullius doctrine law, a theory that professed that indigenous peoples – due to the nature of their cultures – can hold no rights over land. Since the classical international legal system did not embrace human rights norms that could place checks and balances on the exercise of sovereignty, it was from an international legal perspective unproblematic that states invoked the terra nullius doctrine in order to make legal claims to indigenous territories. Section 3 articulates, however, how matters changed when, following the es- tablishment of the United Nations, human rights, including the right to equal- ity, were integrated into the international legal system. This development chal- 1 This chapter draws from a smaller part of a doctoral dissertation defended by the author in 2010 at The Arctic University of Norway – UiT, titled The Saami Traditional Dress and Beauty Pageants–Indigenous Peoples’ Ownership and Self-Determination Over their Cul- tures. -

Transcript of Proceedings

__________________________________________________________ PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION INQUIRY INTO HORIZONTAL FISCAL EQUALISATION MR J COPPEL, Commissioner MS K CHESTER, Commissioner TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS AT BROLGA ROOM, NOVOTEL CBD, 100 THE ESPLANADE, DARWIN, NORTHERN TERRITORY ON TUESDAY, 28 NOVEMBER 2017 AT 12.28 PM Horizontal Fiscal Equalisation 28/11/17 © C'wlth of Australia INDEX Page YOTHU YINDI FOUNDATION MS YANANYMUL MUNUNGGURR 271-288 MS DENISE BOWDEN MR BARRY HANSEN MR BOB BEADMAN AUSTRALIAN EDUCATION UNION MR JARVIS RYAN 288-299 MINERALS COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA MR JOHN BARBER 300-312 MR DREW WAGNER BESPOKE TERRITORY MR PAUL HENDERSON 312-325 COMMUNITY AND PUBLIC SECTOR UNION MS KAY DENSLEY 326-335 ELECTRICAL TRADES UNION MR DAVID HAYES AUSTRALIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, NT DR ROBERT PARKER 336-341 NORTHERN LAND COUNCIL DR JOE VALENTI 342-348 ABORIGINAL MEDICAL SERVICES ALLIANCE, NT MR JOHN PATTERSON 349-360 DR DAVID COOPER MR GERRY WOOD 361-369 Horizontal Fiscal Equalisation 28/11/17 © C'wlth of Australia RESUMED [12.28 pm] MS CHESTER: Okay, folks. We might get underway. Good afternoon, all and welcome to the public hearings for the Productivity Commission 5 Inquiry into Horizontal Fiscal Equalisation, or better known as how we divide up the GST bucket across the states and territories. My name’s Karen Chester. I’m the deputy chair of the Productivity Commission and a Commissioner on this inquiry and I’m joined by my 10 fellow colleague and Commissioner, Jonathan Coppel. I’d like to begin in opening these hearings by acknowledging the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet today the Larrakia people, and I would also like to pay my respects to elders past and present. -

Beyond Reparations: an American Indian Theory of Justice

OHIO STATE LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 66, NUMBER 1, 2005 Beyond Reparations: An American Indian Theory of Justice WILLIAM BRADFORD* It is perhaps impossible to overstate the magnitude of the human injustice perpetrated againstAmerican Indianpeople: indeed,the severity and duration of the harms endured by the original inhabitants of the US. may well rival those suffered by any other group past or present, domestic or international. While financialreparations for certainpast transgressionsmay be appropriateto some groups and situations, the historical and ongoing injustices committed against Indians living within the US. cannot be adequately understood in material terms. Although in recent decades various models of justice have been proposed in respect of a series of gross human injustices, incomplete and even erroneous understandingsof the nature of Indian claims and an overly narrow conception of the potential parameters of remedial justice render these approachesineffectual. This Article presents a alternative theory of justice, termed "Justice as Indigenism" (JAI). As applied JAI commits its practitioners to a sequential process consisting of seven distinct stages: acknowledgment, apology, peacemaking, commemoration, compensation, land restoration, legal reformation, and reconciliation. JAI advances the frontiers of thinking about justice on behalf of Indians in that its normative mission is not the award of materialcompensation or the attribution of blame but ratherthe ultimate healing of the American and Indian nations and the joint authorship -

Indigenous Peoples' Right to Self–Determination

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ RIGHT TO SELF–DETERMINATION AND DEVELOPMENT POLICY FRANCESCA PANZIRONI Thesis submitted to fulfil the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Law University of Sydney 2006 To my mum and daddy for giving me life and freedom Table of contents Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………………….i Synopsis ……………………………………………………………………………………….ii List of figures……………………………………………………………………...…………..iv List of abbreviations…………………………………………………………………………...v Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………...1 Part 1 Indigenous peoples’ quest for self–determination Chapter 1: Indigenous peoples in international law: a historical overview……………..11 1.1 The natural law framework……………………………………………………………….15 1.2 The emergence of the state–centred system and the ‘law of nations’…………………….23 1.3 The positivistic construct of international law……………………………………………29 1.4 The early 20th century: from positivism to pragmatism…………………………………..35 1.5 The United Nations system and indigenous peoples……………………………………..44 Chapter 2: Indigenous peoples’ right to self–determination...…………………………...48 2.1 Indigenous rights and the international human rights system…………………………….48 2.1.1 International Labour Organization’s Conventions on indigenous peoples…………50 2.1.2 The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples……………..53 2.1.3 The Draft American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples…………….65 2.2 The principle of self–determination...…………………………………………………….72 2.3 Indigenous peoples’ right to self–determination………………………………………….82 Chapter 3: Indigenous peoples’ claims to self–determination and the international human rights implementation system……………………...…103 3.1 The United Nations system…………………………………………………………...…104 3.1.1 The United Nations treaty–based human rights system and indigenous claims to self–determination...…………………………………………………….104 (i) The Human Rights Committee…………………………………………....106 (ii) The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination…………. -

ARIA TOP 100 ALBUMS CHART 2007 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND 500000 UNITS TY THIS YEAR ARIA TOP 100 ALBUMS CHART 2007 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO. 1 CALL ME IRRESPONSIBLE Michael Buble <P>4 WMA 9362499111 2 I'M NOT DEAD P!nk <P>8 LAF/SBME 88697075172 3 FUTURE SEX/LOVE SOUNDS Justin Timberlake <P>4 JVE/SBME 82876880622 4 ON A CLEAR NIGHT Missy Higgins <P>3 ELEV/UMA ELEVENCD70 5 THE DUTCHESS Fergie <P>3 A&M/UMA 1707562 6 DREAM DAYS AT THE HOTEL EXISTENCE Powderfinger <P>3 UMA 1735251 7 GRAND NATIONAL The John Butler Trio <P>3 JAR/MGM JBT011 8 LONG ROAD OUT OF EDEN Eagles <P>2 UMA 1749402 9 YOUNG MODERN Silverchair <P>3 ELEV/EMI ELEVENCD63 10 TIMBALAND PRESENTS: SHOCK VALUE Timbaland <P>2 INR/UMA 1726605 11 EXILE ON MAINSTREAM Matchbox Twenty <P>2 WMA 7567899698 12 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT Linkin Park <P>2 WARNER 9362444772 13 DELTA Delta Goodrem <P>2 SBM 88697193922 14 INFINITY ON HIGH Fall Out Boy <P>2 ISL/UMA 1720575 15 SNEAKY SOUND SYSTEM Sneaky Sound System <P>2 MGM WHACK04 16 EYES OPEN Snow Patrol <P>4 UMA 9853178 17 THE TRAVELING WILBURYS COLLECTION The Traveling Wilburys <P>2 RHI/WAR 8122799824 18 LIFE IN CARTOON MOTION Mika <P>2 MER/UMA 1723781 19 THE BEST DAMN THING Avril Lavigne <P>2 RCA/RCR 88697037742 20 ECHOES, SILENCE, PATIENCE & GRACE Foo Fighters <P> RCA/SBME 88697301242 21 THE SWEET ESCAPE Gwen Stefani <P>2 INR/UMA 1717390 22 THE MEMPHIS ALBUM Guy Sebastian <P> SBMG/SBM 88697196012 23 GOOD MORNING REVIVAL Good Charlotte <P> EPI/SBME 88697069352 24 EXTREME BEHAVIOR Hinder <P> UMA 9884987 25 LOOSE Nelly Furtado