Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Jordanjordan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jordan-Health-Equity.Pdf

Health Inequalities in Jordan and their Social Determinants: Evidence and Policy Implications 2019 Disclaimer The analysis, views and policy recommendations in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the World Health Organization (WHO). The report also does not reflect the views of the American University in Cairo. The report is the work of an independent team of authors from the Social Research Center of the American University in Cairo supported by the World Health Organization/ Jordan (WHO /Jordan). Recommended Citation: Khadr, Z., Rashad, H., & Shawky. S. “Health Inequalities in Jordan and their Social Determinants: Evidence and Policy Implications.” The Social Research Center of the American University in Cairo and the World Health Organization/ Jordan (2019). TABLE OF CONTENT Table of content ............................................................................................................................................ 2 List of figures ................................................................................................................................................. 5 List of tables ................................................................................................................................................ 10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................... 12 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... -

National Strategy for Health Sector 2016-2020

The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan High Health Council The National Strategy for Health Sector in Jordan 2016- 2020 His Majesty King Abdullah II Ibn Al –Hussein His Royal Highness Crown Prince Al-Hussein Bin Abdullah II "And to improve the quality of life of each citizen requires attention to heath care as a right for each citizen. The healthy reassured citizen for his health and the health of his children and family is the who is able to work and produce" From the speeches of His Majesty King Abdullah II Bin Al-Hussein Acknowledgements Accomplishment of this national strategy of health sector in Jordan for 2016-2020 by the HHC was made with the support and cooperation of WHO through a participatory approach with all health sectors in Jordan and other related parties, without whom the strategy wouldn't have come into the light. We would like to extend our sincere thanks to the Minister of Health/ Chairman of the HHC (HHC), Dr. Ali Heyasat for his continued support and valued guidance that allowed for the accomplishment of this document. Also we extend our sincere thanks to all who contributed to the completion of this national product particularly the local expert of the strategy, Dr. Musa Ajlouni, who has reviewed the strategy documents that was prepared by the competent committees formed by His Excellency the Chairman of the HHC and headed by the secretary general of HHC, Dr. Hani Brosk Al Kurdi. Also we extend our sincere thanks and gratitude to technical support and assistance provided by the WHO representative in Jordan, and Chair of its mission Dr. -

Health Department

health department annual report 2015 www.unrwa.org health department annual report 2015 www.unrwa.org plaease check the QR Code on back cover © UNRWA, 2016 This document is a formal publication of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) and all rights are reserved by the Organization. The document may, however, be freely reviewed, abstracted, reproduced and translated, in part or in whole, but not for sale or for use in conjunction with commercial purposes. The views expressed in documents by named authors are solely the responsibility of those authors. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document, including tables and maps, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Agency concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by UNRWA in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions accepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. Table of contents Message of the UNRWA Commissioner General and of the WHO Regional Director 6 Foreword of the Director of Health 7 Executive Summary 8 SECTION 1 – Introduction and progress to date 10 UNRWA 10 Health Profile 10 UNRWA Response: Health Reform 12 Family Health Team (FHT) Approach -

Proquest Dissertations

The history of the conquest of Egypt, being a partial translation of Ibn 'Abd al-Hakam's "Futuh Misr" and an analysis of this translation Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hilloowala, Yasmin, 1969- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:08:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/282810 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi-om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectiotiing the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Assessment of Health Needs and Living Conditions of Migrants in Jordan 2011–2012

Assessment of Health Needs and Living Conditions of Migrants in Jordan 2011–2012 International Organization for Migration (IOM) The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. _______________ IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher: International Organization for Migration 17, route des Morillons 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Tel: + 41 22 717 91 11 Fax: + 41 22 798 61 50 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.iom.int _______________ © 2012 International Organization for Migration (IOM) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 54_12 Assessment of Health Needs and Living Conditions of Migrants in Jordan 2011–2012 International Organization for Migration (IOM) In collaboration with the Jordanian Ministry of Health Amman-Jordan International Organization for Migration (IOM) Assessment of Health Needs and Living Conditions of Migrants in Jordan Acknowledgements We, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), would like to express our deep gratitude to His Excellency Dr. -

Jordan Cover.Pmd

AADOLESCENT AND YYOUTH RREPRODUCTIVE HHEALTH IN JJORDORDANAN Status, Issues, Policies, and Programs POLICY is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development under Contract No. HRN-C-00-00-00006-00, beginning July 7, 2000. The project is implemented by Futures Group International in collaboration with Research Triangle Institute and the Centre for Development and Population Activities (CEDPA). Photos selected from M/MC Photoshare at www.jhuccp.org/mmc. Photographers (from top): Lauren Goodsmith, Tod Shapera, and Reproductive Health Association of Cambodia (RHAC). Adolescent Reproductive Health in Jordan Status, Policies, Programs, and Issues Issa S. Almasarweh POLICY Project January 2003 POLICY Project Table of Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................iii Abbreviations .............................................................................................................................................iv 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................1 ARH indicators in Jordan .........................................................................................................................2 2. Social context of ARH........................................................................................................................3 Gender socialization .................................................................................................................................3 -

The Jordanian Diabetes Crisis

The Jordanian Diabetes Crisis International Economic Development Program 2008 Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy University of Michigan Haley Gallagher Maggie Gebhard William Nash Nick Occhipinti Brooklyn Walker 1 Acknowledgements This paper could not have been completed without the valuable time and input received from the following experts: Dr. Mohamed Al Nasa’a Dr. Shadi Azar, University of Michigan Dr. Kamel Ajlouni, National Center for Diabetes, Endocrinology and Genetic Diseases, Amman Dr. Amal Madanat, Al Bashir Hospital, Ministry of Health, Amman Dr. Sana Naffa, World Health Organization, Amman Dr. Yousef Noaimat, Al Bashir Hospital, Ministry of Health, Amman United Nations Relief and Works Agency, Jordan United Nations Development Program, Jordan United States Agency for International Development, Jordan We are truly grateful for their contributions and any errors that remain in the paper are our own. 2 Executive Summary A steadily rising GDP, along with relatively high spending on health care, has allowed Jordan to make a number of significant health advances in the past three decades. Increased life expectancy and immunization rates and reduced child mortality are just a few of the many basic indicators that demonstrate substantial health improvements. Jordan’s dedication to expanding healthcare access and improving quality has produced results so marked that the country has become a popular destination for medical tourism. However, while Jordan’s rapid economic development has allowed it to significantly diminish the prevalence of diseases associated with less developed nations, chronic diseases have become an emerging health crisis. Lifestyle changes including increased caloric intake, decreased consumption of fruits and vegetables, and a decline in physical activity, have contributed to rapidly increasing rates of chronic disease, making them the leading cause of mortality in Jordan. -

A Comparative Study of Women's Health Care

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2016 A Comparative Study of Women’s Health Care: Non-Syrian Refugee Women Living in Amman and Syrian Refugee Women Living in Refugee Camps Megan Kerstein SIT Graduate Institute - Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Maternal and Child Health Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, Obstetrics and Gynecology Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Women's Health Commons Recommended Citation Kerstein, Megan, "A Comparative Study of Women’s Health Care: Non-Syrian Refugee Women Living in Amman and Syrian Refugee Women Living in Refugee Camps" (2016). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2373. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2373 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Comparative Study of Women’s Health Care: Non-Syrian Refugee Women Living in Amman and Syrian Refugee Women Living in Refugee Camps Megan Kerstein Washington University in St. Louis Global Health and the Environment SIT, Middle East, Jordan, Amman Academic Director: Dr. Ashraf F. Alqudah, Ph.D Project Advisor: Dr. Mohammad Al-Shrouf Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Modernization and Social Change, SIT Study Abroad, Spring 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………...5 Abstract………………………………………………………………………….6 Introduction……………………………………………………………………...7 1 I. -

HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT March 2014 – Report to the Ministry of Health

HASHEMITE KINGDOM OF JORDAN SYRIAN CRISIS HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT March 2014 – Report to the Ministry of Health EXECUTIVE SUMMARY With over 1 out of 10 people actually living in Jordan being a Syrian refugee, the Syrian crisis has a great impact on the country in demographic, social and economic terms. Over 80% refugees reside in host communities which require more complex interventions to reach out refugee, respond to their needs and mitigate the impact on the host communities. While demographic data are far from being accurate due to mobility and the refusal of some refugees to register, it is however clear that densely populated areas surrounding important economic centres are attracting significant numbers of refugees, with among other pull factors the cheaper housing costs. Significant numbers of humanitarian actors are concentrating their efforts on camp settings and on the Northern governorates. Financial means have also been channelled to the main refugee camp of Zaatari, more recently to Azraq camp and to the northern governorates. However and in view of the fact that governorates located at the centre of the country such as Zarqa Governorate host significant refugee population and vulnerable host communities, there is a lack of services to address basic needs of these populations. As per a May 2012 Government of Jordan cabinet decree, Syrian refugees with valid registration – both up-to-date UNHCR registration certificate and Ministry of Interior Service card delivered by a police station in the same district of residence - receive free primary, secondary and tertiary health care services at MoH facilities. Refugees who do not have the appropriate registration documents – valid UNHCR and MoI documents - are served by UNHCR Jordan Health Aid Society (JHAS) clinics and Mobile Medical Units (MMUs) as well as NGO and private clinics. -

UNRWA Health Department Annual Report 2018

health department annual report 2018 www.unrwa.org health department - annual report 2018 3 health department annual report 2018 www.unrwa.org 4 health department - annual report 2018 please check the QR Code on back cover health department - annual report 2018 5 © 2019 United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East This document is a formal publication of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) and all rights are reserved by the Organization. The document may, however, be freely reviewed, abstracted, reproduced and translated, in part or in whole, but not for sale or for use in conjunction with commercial purposes. The views expressed in documents by named authors are solely the responsibility of those authors. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document, including tables and maps, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Agency concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by UNRWA in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions accepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. www.unrwa.org Cover Photo: 2018 UNRWA Photo by Carlos Pérez Osorio 6 health department - annual report 2018 table of contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ......................................................................................................................... 9 Message of the UNRWA Commissioner General and of the WHO Regional Director ................................. -

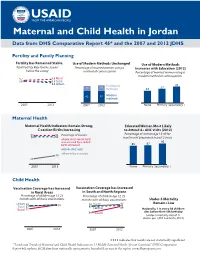

Maternal and Child Health in Jordan Data from DHS Comparative Report 46* and the 2007 and 2012 JDHS

Maternal and Child Health in Jordan Data from DHS Comparative Report 46* and the 2007 and 2012 JDHS Fertility and Family Planning Fertility has Remained Stable Use of Modern Methods Unchanged Use of Modern Methods Total Fertility Rate for the 3 years Percentage of married women using a Increases with Education (2012) before the survey method of contraception Percentage of married women using a modern method of contraception 3.7 3.9 Rural 3.6 3.5 Total 3.4 Urban Traditional 43 15 19 methods 32 37 42 42 Modern methods 2007 2012 2007 2012 None Primary Secondary + Maternal Health Maternal Health Indicators Remain Strong; Educated Women Most Likely C-section Births Increasing to Attend 4+ ANC visits (2012) 99 99 Percentage of women: Percentage of women age 15-49 for 94 94 most recent pregnancy in past 2 years whose most recent birth was assisted by a skilled 95 birth attendant 85 87 with 4+ ANC visits delivered by c-section 30 20 2007 2012 None Primary Secondary + Child Health Vaccination Coverage has Increased Vaccination Coverage has Increased in Rural Areas in South and North Regions Percentage of children age 12-23 Percentage of children age 12-23 months with all basic vaccinations months with all basic vaccinations Under-5 Mortality Urban North 95 Remains Low 89 93 90 93 Total 87 89 Central 89 Rural 77 Nationally, 1 in every 50 children 64 South dies before their 5th birthday (under-5 mortality rate of 21 deaths per 1,000 live births, 2012) 2007 2012 2007 2012 indicates that results are not statistically significant *“Levels and Trends of Maternal and Child Health Indicators in 11 Middle East and North African Countries” (DHS Comparative Report 46) explores MCH data from nationally representative household surveys in the region. -

North Caucasus: the Challenges of Integration (IV): Economic and Social Imperatives

North Caucasus: The Challenges of Integration (IV): Economic and Social Imperatives Europe Report N°237 | 7 July 2015 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Economy of the Crisis Region ................................................................................... 4 A. Common Features ...................................................................................................... 5 B. Regional Differences .................................................................................................. 9 Chechnya .............................................................................................................. 9 Dagestan and Stavropol Kray ............................................................................... 10 Ingushetia and Karachay-Cherkessia ................................................................... 12 Kabardino-Balkaria and North Ossetia-Alania .................................................... 12 C. Agriculture ................................................................................................................