Manual of Good Practices in Small Scale Irrigation in the Sahel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune Effectiveness Prepared for United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mali Mission, Democracy and Governance (DG) Team Prepared by Dr. Lynette Wood, Team Leader Leslie Fox, Senior Democracy and Governance Specialist ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Third Floor Burlington, VT 05401 USA Telephone: (802) 658-3890 FAX: (802) 658-4247 in cooperation with Bakary Doumbia, Survey and Data Management Specialist InfoStat, Bamako, Mali under the USAID Broadening Access and Strengthening Input Market Systems (BASIS) indefinite quantity contract November 2000 Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS.......................................................................... i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................... ii 1 INDICATORS OF AN EFFECTIVE COMMUNE............................................... 1 1.1 THE DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE..............................................1 1.2 THE EFFECTIVE COMMUNE: A DEVELOPMENT HYPOTHESIS..........................................2 1.2.1 The Development Problem: The Sound of One Hand Clapping ............................ 3 1.3 THE STRATEGIC GOAL – THE COMMUNE AS AN EFFECTIVE ARENA OF DEMOCRATIC LOCAL GOVERNANCE ............................................................................4 1.3.1 The Logic Underlying the Strategic Goal........................................................... 4 1.3.2 Illustrative Indicators: Measuring Performance at the -

VEGETALE : Semences De Riz

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ********* UN PEUPLE- UN BUT- UNE FOI DIRECTION NATIONALE DE L’AGRICULTURE APRAO/MALI DNA BULLETIN N°1 D’INFORMATION SUR LES SEMENCES D’ORIGINE VEGETALE : Semences de riz JANVIER 2012 1 LISTE DES ABREVIATIONS ACF : Action Contre la Faim APRAO : Amélioration de la Production de Riz en Afrique de l’Ouest CAPROSET : Centre Agro écologique de Production de Semences Tropicales CMDT : Compagnie Malienne de Développement de textile CRRA : Centre Régional de Recherche Agronomique DNA : Direction Nationale de l’Agriculture DRA : Direction Régionale de l’Agriculture ICRISAT: International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics IER : Institut d’Economie Rurale IRD : International Recherche Développement MPDL : Mouvement pour le Développement Local ON : Office du Niger ONG : Organisation Non Gouvernementale OP : Organisation Paysanne PAFISEM : Projet d’Appui à la Filière Semencière du Mali PDRN : Projet de Diffusion du Riz Nérica RHK : Réseau des Horticulteurs de Kayes SSN : Service Semencier National WASA: West African Seeds Alliancy 2 INTRODUCTION Le Mali est un pays à vocation essentiellement agro pastorale. Depuis un certain temps, le Gouvernement a opté de faire du Mali une puissance agricole et faire de l’agriculture le moteur de la croissance économique. La réalisation de cette ambition passe par la combinaison de plusieurs facteurs dont la production et l’utilisation des semences certifiées. On note que la semence contribue à hauteur de 30-40% dans l’augmentation de la production agricole. En effet, les semences G4, R1 et R2 sont produites aussi bien par les structures techniques de l’Etat (Service Semencier National et l’IER) que par les sociétés et Coopératives semencières (FASO KABA, Cigogne, Comptoir 2000, etc.) ainsi que par les producteurs individuels à travers le pays. -

M700kv1905mlia1l-Mliadm22305

! ! ! ! ! RÉGION DE MOPTI - MALI ! Map No: MLIADM22305 ! ! 5°0'W 4°0'W ! ! 3°0'W 2°0'W 1°0'W Kondi ! 7 Kirchamba L a c F a t i Diré ! ! Tienkour M O P T I ! Lac Oro Haib Tonka ! ! Tombouctou Tindirma ! ! Saréyamou ! ! Daka T O M B O U C T O U Adiora Sonima L ! M A U R I T A N I E ! a Salakoira Kidal c Banikane N N ' T ' 0 a Kidal 0 ° g P ° 6 6 a 1 1 d j i ! Tombouctou 7 P Mony Gao Gao Niafunké ! P ! ! Gologo ! Boli ! Soumpi Koulikouro ! Bambara-Maoude Kayes ! Saraferé P Gossi ! ! ! ! Kayes Diou Ségou ! Koumaïra Bouramagan Kel Zangoye P d a Koulikoro Segou Ta n P c ! Dianka-Daga a ! Rouna ^ ! L ! Dianké Douguel ! Bamako ! ougoundo Leré ! Lac A ! Biro Sikasso Kormou ! Goue ! Sikasso P ! N'Gorkou N'Gouma ! ! ! Horewendou Bia !Sah ! Inadiatafane Koundjoum Simassi ! ! Zoumoultane-N'Gouma ! ! Baraou Kel Tadack M'Bentie ! Kora ! Tiel-Baro ! N'Daba ! ! Ambiri-Habe Bouta ! ! Djo!ndo ! Aoure Faou D O U E N T Z A ! ! ! ! Hanguirde ! Gathi-Loumo ! Oualo Kersani ! Tambeni ! Deri Yogoro ! Handane ! Modioko Dari ! Herao ! Korientzé ! Kanfa Beria G A O Fraction Sormon Youwarou ! Ourou! hama ! ! ! ! ! Guidio-Saré Tiecourare ! Tondibango Kadigui ! Bore-Maures ! Tanal ! Diona Boumbanke Y O U W A R O U ! ! ! ! Kiri Bilanto ! ! Nampala ! Banguita ! bo Sendegué Degue -Dé Hombori Seydou Daka ! o Gamni! d ! la Fraction Sanango a Kikara Na! ki ! ! Ga!na W ! ! Kelma c Go!ui a Te!ye Kadi!oure L ! Kerengo Diambara-Mouda ! Gorol-N! okara Bangou ! ! ! Dogo Gnimignama Sare Kouye ! Gafiti ! ! ! Boré Bossosso ! Ouro-Mamou ! Koby Tioguel ! Kobou Kamarama Da!llah Pringa! -

Rapport Mensuel De Monitoring De Protection Mali

RAPPORT MENSUEL DE MONITORING DE PROTECTION MALI N° 11 - NOVEMBRE 2020 1 I - Aperçu de l’environnement de sécuritaire et de protection Nombre de violations en novembre: 286 Résumé des tendances en 2020 Sur un total de 3 714 violations enregistrées entre janvier et novembre 2020, les atteintes Nombre de violations en 2020: 3,714 au droit à la propriété et les atteintes à l’intégrité physique/psychique sont les deux catégories les plus élevées chaque mois sans exception. Au deuxième trimestre de 2020, les atteintes au droit à la vie ont nettement augmenté. Le nombre de mouvements forcés de 493 501 population est directement lié au nombre d'atteintes au droit à la vie. Les atteintes à la 402 363 388 351 liberté et à la sécurité de la personne ont connu un pic pendant la période électorale du 367 286 mois d’avril à Mopti et Tombouctou, et ont majoritairement été encore plus fréquemment 332 rapportées à Mopti et Ségou en juin et juillet. La saison des pluies et des intiatives de 144 88 réconciliation entre Dogon et Peulh au plateau Dogon dans la région de Mopti ont entrainé 57 57 49 49 57 57 57 57 57 57 une réduction des violations pendant le mois d'aout et de septembre. Suite à cette accalmie, 49 les attaques de villages dans le centre du pays ont encore augmenté. Depuis le mois d'octobre, un nombre accru d'atteintes à la sécurité de la personne (surtout des enlèvements) a été observé, majoritairement à Niono, région de Ségou où les affrontements Nombre de moniteurs inter-communautaires n'ont cessé de croître. -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

Régions De SEGOU Et MOPTI République Du Mali P! !

Régions de SEGOU et MOPTI République du Mali P! ! Tin Aicha Minkiri Essakane TOMBOUCTOUC! Madiakoye o Carte de la ville de Ségou M'Bouna Bintagoungou Bourem-Inaly Adarmalane Toya ! Aglal Razelma Kel Tachaharte Hangabera Douekiré ! Hel Check Hamed Garbakoira Gargando Dangha Kanèye Kel Mahla P! Doukouria Tinguéréguif Gari Goundam Arham Kondi Kirchamba o Bourem Sidi Amar ! Lerneb ! Tienkour Chichane Ouest ! ! DiréP Berabiché Haib ! ! Peulguelgobe Daka Ali Tonka Tindirma Saréyamou Adiora Daka Salakoira Sonima Banikane ! ! Daka Fifo Tondidarou Ouro ! ! Foulanes NiafounkoéP! Tingoura ! Soumpi Bambara-Maoude Kel Hassia Saraferé Gossi ! Koumaïra ! Kanioumé Dianké ! Leré Ikawalatenes Kormou © OpenStreetMap (and) contributors, CC-BY-SA N'Gorkou N'Gouma Inadiatafane Sah ! ! Iforgas Mohamed MAURITANIE Diabata Ambiri-Habe ! Akotaf Oska Gathi-Loumo ! ! Agawelene ! ! ! ! Nourani Oullad Mellouk Guirel Boua Moussoulé ! Mame-Yadass ! Korientzé Samanko ! Fraction Lalladji P! Guidio-Saré Youwarou ! Diona ! N'Daki Tanal Gueneibé Nampala Hombori ! ! Sendegué Zoumané Banguita Kikara o ! ! Diaweli Dogo Kérengo ! P! ! Sabary Boré Nokara ! Deberé Dallah Boulel Boni Kérena Dialloubé Pétaka ! ! Rekerkaye DouentzaP! o Boumboum ! Borko Semmi Konna Togueré-Coumbé ! Dogani-Beré Dagabory ! Dianwely-Maoundé ! ! Boudjiguiré Tongo-Tongo ! Djoundjileré ! Akor ! Dioura Diamabacourou Dionki Boundou-Herou Mabrouck Kebé ! Kargue Dogofryba K12 Sokora Deh Sokolo Damada Berdosso Sampara Kendé ! Diabaly Kendié Mondoro-Habe Kobou Sougui Manaco Deguéré Guiré ! ! Kadial ! Diondori -

USAID/ Mali SIRA

USAID/ Mali SIRA Selective Integrated Reading Activity Quarterly Report April to June 2018 July 30, 2018 Submitted to USAID/Mali by Education Development Center, Inc. in accordance with Task Order No. AID-688-TO-16-00005 under IDIQC No. AID-OAA-I-14- 00053. This report is made possible by the support of the American People jointly through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Government of Mali. The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Education Development Center, Inc. (EDC) and, its partners and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Table of Contents ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................... 2 I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 3 II. Key Activities and Results ....................................................................................................... 5 II.A. – Intermediate Result 1: Classroom Early Grade Reading Instruction Improved ........................ 5 II.A.1. Sub-Result 1.1: Student’s access to evidence-based, conflict and gender sensitive, early Grade reading material increased .................................................................................................. 5 II.A.2. Sub IR1.2: Inservice teacher training in evidence-based early Grade reading improved ..... 6 II.A.3. Sub-Result 1.3: Teacher coaching and supervision -

Spécialdfc Agriculture Externes Durable Àfaibles Apports MELCA Bougouma Mbaye Fall Et Ousmane Traoré Diagne

I T O I N D É A F R I Q U E F R A NC E OPHON vrier pcial Revue sur l’Agriculture durable à faibles apports externes 1 La rédaction a mis le plus grand soin à s’assurer que le contenu de la présente revue est aussi exact que possible. Mais, en dernier ressort,seuls les auteurs sont responsables du contenu Agriculture durable à faibles apports externes de chaque article. N° Spécial DFC AGRIDAPE est l’édition régionale Les opinions exprimées dans cette Afrique francophone du magazine Farming revue n’engagent que leurs auteurs. Matters produit par le Réseau AgriCultures. La rédaction encourage les lecteurs ISSN N°0851-7932 à photocopier et à faire circuler ces articles. Vous voudrez bien cependant citer l’auteur et la source et nous envoyer un exemplaire de votre publication. Édité par : IED Afrique 24, Sacré Coeur III – Dakar BP : 5579 Dakar-Fann, Sénégal Chères lectrices, chers lecteurs, Téléphone : +221 33 867 10 58 - Fax : +221 33 867 10 59 E-mail : [email protected] - Site Web : www.iedafrique.org La revue AGRIDAPE vous revient avec un nouveau Coordonnateur : Birame Faye numéro spécial. Celui-ci porte un modèle, Comité éditorial : un mécanisme innovant qui a permis à des Bara Guèye, Mamadou Fall, Rokhaya Faye, Momath Talla Ndao, communautés à la base et à des collectivités Aly Bocoum, Yacouba Dème, Lancelot Soumelong Ehode, Djibril Diop, Ced Hesse, Yamadou Diallo territoriales d’accéder à des financements dans le cadre de la mise en œuvre du projet Décentralisation Ce numéro a été réalisé avec l’appui de Amadou Ndiaye (Sénégal) des Fonds Climat (DFC) à Mopti (Mali) et à Kaffrine et Abdoulaye Cissé (Mali) (Sénégal), dans le but de renforcer les capacités Administration : de résilience des populations locales face au Maïmouna Dieng Lagnane changement climatique. -

La Lettre D'action Mopti

N° 45 - Juin 2020 LA LETTRE D’ACTION MOPTI Cette lettre d’Action-Mopti rend compte des activités pendant la période de pandémie à Mopti et à Maurepas À Maurepas… Dans le cadre des mesures de confinement, Didier, chargé de mission, est en télétravail et Sophie, secrétaire, est présente au siège à Maurepas. Des visioconférences ont maintenu un lien entre les membres du bureau et l’équipe malienne. L’équipe de l’éducation à la citoyenneté et à la solidarité internationale n’a pas pu intervenir au collège Alexandre Dumas de Maurepas dans les classes de 5e et 6e. Suite aux contraintes sanitaires, l’arrêt des comptes et l’assemblée générale sont reportés à l’automne. À Mopti… Des mesures barrières sont appliquées par l’équipe : désinfection des locaux, gel hydroalcoolique, masques… Des microprogrammes de prévention ont été diffusés en 4 langues sur plusieurs radios locales. Des kits de lavage des mains ont été installés dans les mairies, les CSCOM et les centres d’écoute Alpha. Des distributions de savons, gel hydroalcoolique, gants et thermomètres ont eu lieu. Mairie de Konna Mairie de Korombana CSCOM de Konna Siège social France : 7, rue Paul Drussant – 78310 Maurepas - Tél : +33 01.30.62.62.42 – Fax : 09.54.42.10.95 Courriel : [email protected] / [email protected] Action-Mopti Mali : BP 202- Mopti – Mali – Tél & Fax +223 21 430 363 – www.actionmopti.com Association à but non lucratif, loi 1901, n° 3363 Activités de sensibilisation et remise de kits Région Cercle Communes Nombre de personnes ayant reçu les Nombre de structures -

Bulletin Sap N°327

PRESIDENCE DE LA REPUBLIQUE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ------------***------------ ------------***------------ COMMISSARIAT A LA SECURITE ALIMENTAIRE Un Peuple-Un But-Une Foi ------------***------------ SYSTEME D’ALERTE PRECOCE (S.A.P) BP. 2660, Bamako-Mali Tel :(223) 20 74 54 39 ; Adresse email : [email protected] Adresse Site Web : www.sapmali.com BULLETIN SAP N°327 Mars 2014 QU’EST-CE QUE LE SAP ? Afin de mieux prévoir les crises alimentaires et pour améliorer la mise en œuvre des aides nécessaires, le Ministère de l’administration Territoriale et des Collectivités Locales a mis en place un groupe Système d’Alerte Précoce du risque alimentaire (S.A.P.) Le groupe S.A.P. a pour mission de répondre aux questions suivantes : Quelles sont les zones et les populations risquant de connaître des problèmes alimentaires ou nutritionnels ? Quelles sont les aides à fournir ? Comment les utiliser ? Il bénéficie pour ce faire de l’appui du projet S.A.P. Le S.A.P. surveille les zones traditionnellement « à risque », c’est à dire les zones ayant déjà connu des crises alimentaires sévères, soit les 349 communes situées essentiellement au nord du 14ème parallèle. Cependant avec l’évolution du risque alimentaire (lié au marché, lié à la pauvreté) le SAP surveille l’ensemble des 703 communes du pays depuis 2004. Le S.A.P. se base sur une collecte permanente de données liées à la situation alimentaire et nutritionnelle des populations. Ces informations couvrent des domaines très divers tels la pluviométrie, l’évolution des cultures, l'élevage, les prix sur les marchés, les migrations de populations, leurs habitudes et réserves alimentaires, ainsi que leur état de santé. -

Ocha Mopti Commune Da

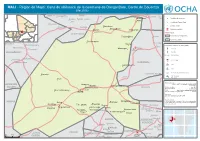

MALI - Région de Mopti: Carte de référence de la commune de Dangol Bore, Cercle de Douentza (Mai 2016) DofinaSAHARA Oualo Tambeni Dindia OCCIDENTAL Dianguinare Deri ALGERIE Kersani Senore Takouti Sobo Ouro-diam Chef lieu de commune Boukourintie Allah Noradji Dari Localité de Dangol Bore Sare Tombouctou MAURITANIE Boukourintie-oKidaluro Dimango N'dissore Mounkeye Localité voisine Bagui Sounteye Norkala Magoubeye Gao Hororo N'doumpa Structure sanitaire Mopti Akka Route Korientzé NIGER KayesKera Segou DJAPTODJI SENEGAL KoulikouroKorientzé Korientze Commune de Dangol Bore Bamako BURKINA FASO Foulacriabes Ibrizaz GUINEE Sikasso NIGERIA Commune voisine GHANA BENIN COTE D'IVOIRE TOGO Bore-maures Kel-eguel Massama Youna Moussokourare Population estimée en 2015 (DNP) Tanal M'bessema CSCOM Tiecourare Madougou 16 190 DIONA KOROMBANA 16 359 Densité: 13 hb/Km2 Gouloumbou Keretogo 1 CSCOM Madina-coura KORAROU Sansa-tounta ND ND 1 Ecole de première cycle Kerengo Diambara-mouda Goui 34 forages 45 puits Teye Nom de la carte: OUROUBE Niongolo OCHA_MOPTI_COMMUNE_DANGOL BORE Manko Gnimignama A3_20160516 DOUDE Falembougou DEBERE Date de création: Avril 2016 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Ouori-n'dounkoye CSCOM Web : http://mali.humanitarianresponse.info BORE Echelle nominale sur papier A3 : 1:250,000 Source(s): Données spatiales: DNCT, DNP, DTM Avertissements: Adioubata Les Nations Unies ne sauraient être tenues responsables KONNA Amba Bobowel de la qualité des limites, des noms et des désignations Dounkoy Ena-tioki Doumbara utilisés sur cette carte Tete-ompto Some Koira Noumboli Forgeron-issa Beri Batouma Ouro-lenga Kiro Noumori-soki Dimbatoro Tabako Songadji Koressana Dempari Bedjima Semari-dangani Nema Tiboki Ibissa Mougui Dembeli BORKO KOUBEWEL Nomgoro KOUNDIA Mello Adia CSCOM Dindari BORKO Temba-neri Neri KENDIE Tim-tam DIAMNATI LOWOL DOGANI BERE Endeguem 0 3.5 7 Km GUEOU Sassambourou CONFES- Olkia Menthy Oume SIONNEL Saoura-kom. -

Humanitarian Situation Report No. 8

Mali Humanitarian Situation Report No. 8 © UNICEF/C99R1729/Dicko Situation in Numbers 3,500,000 children in need of humanitarian © UNICEF/318A7554/Dicko assistance (OCHA Mali HNO revised Reporting Period: 01 to 31 August 2020 August 2020) Highlights 6,800,000 people in need of humanitarian • A military coup d'etat on August 18, 2020 resulted in the removal of the assistance President and the Government as well as the introduction of political (OCHA Mali HNO revised August 2020) and financial sanctions by the regional organization ECOWAS. • 96,629 (including 23,720 in August) cases of severe malnutrition were treated and 892,846 under 5 five children screened during the seasonal malaria prevention integrated mass campaign. 287,496 • 3,803 children affected by humanitarian crises, in particular due to conflict, were reached with community based psychosocial support in Internally displaced people (National Directorate of Social Development - DNDS. Bamako district, Gao, Kidal, Ménaka, Mopti and Timbuktu regions. Matrix for Monitoring Displacement (DTM),30 July 2020) • UNICEF provided 15,218 Households (91,308 people) with short term emergency water treatment and hygiene kits as well as sustainable water supply services as of August 31, 2020 in Mopti, Gao, Kidal, Timbuktu and Taoudenit regions. • Outbreak of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV2) in the UNICEF Appeal 2020 northern region of Mali with 2 confirmed cases in Menaka region US$ 51,85 million UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status Funds Received $ 16,6 M (33%) Funding gap $ 31,3 M (60 %) Carry-forward, *Funding available includes carry-over and funds received in the current year.