A Study of Korean Phonology and Morphology in a Derivational Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards a Practical Phonology of Korean

Towards a practical phonology of Korean Research Master programme in Linguistics Leiden University Graduation thesis Lorenzo Oechies Supervisor: Dr. J.M. Wiedenhof Second reader: Dr. A.R. Nam June 1, 2020 The blue silhouette of the Korean peninsula featured on the front page of this thesis is taken from the Korean Unification Flag (Wikimedia 2009), which is used to represent both North and South Korea. Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... iii 0. Conventions ............................................................................................................................................... vii 0.1 Romanisation ........................................................................................................................................................ vii 0.2 Glosses .................................................................................................................................................................... viii 0.3 Symbols .................................................................................................................................................................. viii 0.4 Phonetic transcription ........................................................................................................................................ ix 0.5 Phonemic transcription..................................................................................................................................... -

South Korea Section 3

DEFENSE WHITE PAPER Message from the Minister of National Defense The year 2010 marked the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. Since the end of the war, the Republic of Korea has made such great strides and its economy now ranks among the 10-plus largest economies in the world. Out of the ashes of the war, it has risen from an aid recipient to a donor nation. Korea’s economic miracle rests on the strength and commitment of the ROK military. However, the threat of war and persistent security concerns remain undiminished on the Korean Peninsula. North Korea is threatening peace with its recent surprise attack against the ROK Ship CheonanDQGLWV¿ULQJRIDUWLOOHU\DW<HRQS\HRQJ Island. The series of illegitimate armed provocations by the North have left a fragile peace on the Korean Peninsula. Transnational and non-military threats coupled with potential conflicts among Northeast Asian countries add another element that further jeopardizes the Korean Peninsula’s security. To handle security threats, the ROK military has instituted its Defense Vision to foster an ‘Advanced Elite Military,’ which will realize the said Vision. As part of the efforts, the ROK military complemented the Defense Reform Basic Plan and has UHYDPSHGLWVZHDSRQSURFXUHPHQWDQGDFTXLVLWLRQV\VWHP,QDGGLWLRQLWKDVUHYDPSHGWKHHGXFDWLRQDOV\VWHPIRURI¿FHUVZKLOH strengthening the current training system by extending the basic training period and by taking other measures. The military has also endeavored to invigorate the defense industry as an exporter so the defense economy may develop as a new growth engine for the entire Korean economy. To reduce any possible inconveniences that Koreans may experience, the military has reformed its defense rules and regulations to ease the standards necessary to designate a Military Installation Protection Zone. -

Vowel Quality and Phonological Projection

i Vowel Quality and Phonological Pro jection Marc van Oostendorp PhD Thesis Tilburg University September Acknowledgements The following p eople have help ed me prepare and write this dissertation John Alderete Elena Anagnostop oulou Sjef Barbiers Outi BatEl Dorothee Beermann Clemens Bennink Adams Bo domo Geert Bo oij Hans Bro ekhuis Norb ert Corver Martine Dhondt Ruud and Henny Dhondt Jo e Emonds Dicky Gilb ers Janet Grijzenhout Carlos Gussenhoven Gert jan Hakkenb erg Marco Haverkort Lars Hellan Ben Hermans Bart Holle brandse Hannekevan Ho of Angeliek van Hout Ro eland van Hout Harry van der Hulst Riny Huybregts Rene Kager HansPeter Kolb Emiel Krah mer David Leblanc Winnie Lechner Klarien van der Linde John Mc Carthy Dominique Nouveau Rolf Noyer Jaap and Hannyvan Oosten dorp Paola Monachesi Krisztina Polgardi Alan Prince Curt Rice Henk van Riemsdijk Iggy Ro ca Sam Rosenthall Grazyna Rowicka Lisa Selkirk Chris Sijtsma Craig Thiersch MiekeTrommelen Rub en van der Vijver Janneke Visser Riet Vos Jero en van de Weijer Wim Zonneveld Iwant to thank them all They have made the past four years for what it was the most interesting and happiest p erio d in mylife until now ii Contents Intro duction The Headedness of Syllables The Headedness Hyp othesis HH Theoretical Background Syllable Structure Feature geometry Sp ecication and Undersp ecicati on Skeletal tier Mo del of the grammar Optimality Theory Data Organisation of the thesis Chapter Chapter -

D2492609215cd311123628ab69

Acknowledgements Publisher AN Cheongsook, Chairperson of KOFIC 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu. Seoul, Korea (130-010) Editor in Chief Daniel D. H. PARK, Director of International Promotion Department Editors KIM YeonSoo, Hyun-chang JUNG English Translators KIM YeonSoo, Darcy PAQUET Collaborators HUH Kyoung, KANG Byeong-woon, Darcy PAQUET Contributing Writer MOON Seok Cover and Book Design Design KongKam Film image and still photographs are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), GIFF (Gwangju International Film Festival) and KIFV (The Association of Korean Independent Film & Video). Korean Film Council (KOFIC), December 2005 Korean Cinema 2005 Contents Foreword 04 A Review of Korean Cinema in 2005 06 Korean Film Council 12 Feature Films 20 Fiction 22 Animation 218 Documentary 224 Feature / Middle Length 226 Short 248 Short Films 258 Fiction 260 Animation 320 Films in Production 356 Appendix 386 Statistics 388 Index of 2005 Films 402 Addresses 412 Foreword The year 2005 saw the continued solid and sound prosperity of Korean films, both in terms of the domestic and international arenas, as well as industrial and artistic aspects. As of November, the market share for Korean films in the domestic market stood at 55 percent, which indicates that the yearly market share of Korean films will be over 50 percent for the third year in a row. In the international arena as well, Korean films were invited to major international film festivals including Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Locarno, and San Sebastian and received a warm reception from critics and audiences. It is often said that the current prosperity of Korean cinema is due to the strong commitment and policies introduced by the KIM Dae-joong government in 1999 to promote Korean films. -

2018/2019 Season

Saturday, April 6, 2019 1:00 & 6:30 pm 2018/2019 SEASON Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. Kevin McKenzie Kara Medoff Barnett ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Alexei Ratmansky ARTIST IN RESIDENCE STELLA ABRERA ISABELLA BOYLSTON MISTY COPELAND HERMAN CORNEJO SARAH LANE ALBAN LENDORF GILLIAN MURPHY HEE SEO CHRISTINE SHEVCHENKO DANIIL SIMKIN CORY STEARNS DEVON TEUSCHER JAMES WHITESIDE SKYLAR BRANDT ZHONG-JING FANG THOMAS FORSTER JOSEPH GORAK ALEXANDRE HAMMOUDI BLAINE HOVEN CATHERINE HURLIN LUCIANA PARIS CALVIN ROYAL III ARRON SCOTT CASSANDRA TRENARY KATHERINE WILLIAMS ROMAN ZHURBIN Alexei Agoudine Joo Won Ahn Mai Aihara Nastia Alexandrova Sierra Armstrong Alexandra Basmagy Hanna Bass Aran Bell Gemma Bond Lauren Bonfiglio Kathryn Boren Zimmi Coker Luigi Crispino Claire Davison Brittany DeGrofft* Scout Forsythe Patrick Frenette April Giangeruso Carlos Gonzalez Breanne Granlund Kiely Groenewegen Melanie Hamrick Sung Woo Han Courtlyn Hanson Emily Hayes Simon Hoke Connor Holloway Andrii Ishchuk Anabel Katsnelson Jonathan Klein Erica Lall Courtney Lavine Virginia Lensi Fangqi Li Carolyn Lippert Isadora Loyola Xuelan Lu Duncan Lyle Tyler Maloney Hannah Marshall Betsy McBride Cameron McCune João Menegussi Kaho Ogawa Garegin Pogossian Lauren Post Wanyue Qiao Luis Ribagorda Rachel Richardson Javier Rivet Jose Sebastian Gabe Stone Shayer Courtney Shealy Kento Sumitani Nathan Vendt Paulina Waski Marshall Whiteley Stephanie Williams Remy Young Jin Zhang APPRENTICES Jacob Clerico Jarod Curley Michael de la Nuez Léa Fleytoux Abbey Marrison Ingrid Thoms Clinton Luckett ASSISTANT ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Ormsby Wilkins MUSIC DIRECTOR Charles Barker David LaMarche PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR CONDUCTOR PRINCIPAL BALLET MISTRESS Susan Jones BALLET MASTERS Irina Kolpakova Carlos Lopez Nancy Raffa Keith Roberts *2019 Jennifer Alexander Dancer ABT gratefully acknowledges: Avery and Andrew F. -

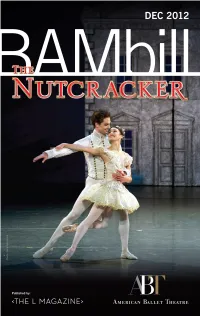

The Nutcracker

American Ballet Theatre Kevin McKenzie Rachel S. Moore Artistic Director Chief Executive Officer Alexei Ratmansky Artist in Residence HERMAN CORNEJO · MARCELO GOMES · DAVID HALLBERG PALOMA HERRERA · JULIE KENT · GILLIAN MURPHY · VERONIKA PART XIOMARA REYES · POLINA SEMIONOVA · HEE SEO · CORY STEARNS STELLA ABRERA · KRISTI BOONE · ISABELLA BOYLSTON · MISTY COPELAND ALEXANDRE HAMMOUDI · YURIKO KAJIYA · SARAH LANE · JARED MATTHEWS SIMONE MESSMER · SASCHA RADETSKY · CRAIG SALSTEIN · DANIIL SIMKIN · JAMES WHITESIDE Alexei Agoudine · Eun Young Ahn · Sterling Baca · Alexandra Basmagy · Gemma Bond · Kelley Boyd Julio Bragado-Young · Skylar Brandt · Puanani Brown · Marian Butler · Nicola Curry · Gray Davis Brittany DeGrofft · Grant DeLong · Roddy Doble · Kenneth Easter · Zhong-Jing Fang · Thomas Forster April Giangeruso · Joseph Gorak · Nicole Graniero · Melanie Hamrick · Blaine Hoven · Mikhail Ilyin Gabrielle Johnson · Jamie Kopit · Vitali Krauchenka · Courtney Lavine · Isadora Loyola · Duncan Lyle Daniel Mantei · Elina Miettinen · Patrick Ogle · Luciana Paris · Renata Pavam · Joseph Phillips · Lauren Post Kelley Potter · Luis Ribagorda · Calvin Royal III · Jessica Saund · Adrienne Schulte · Arron Scott Jose Sebastian · Gabe Stone Shayer · Christine Shevchenko · Sarah Smith* · Sean Stewart · Eric Tamm Devon Teuscher · Cassandra Trenary · Leann Underwood · Karen Uphoff · Luciana Voltolini Paulina Waski · Jennifer Whalen · Katherine Williams · Stephanie Williams · Roman Zhurbin Apprentices Claire Davison · Lindsay Karchin · Kaho Ogawa · Sem Sjouke · Bryn Watkins · Zhiyao Zhang Victor Barbee Associate Artistic Director Ormsby Wilkins Music Director Charles Barker David LaMarche Principal Conductor Conductor Ballet Masters Susan Jones · Irina Kolpakova · Clinton Luckett · Nancy Raffa * 2012 Jennifer Alexander Dancer ABT gratefully acknowledges Avery and Andrew Barth for their sponsorship of the corps de ballet in memory of Laima and Rudolph Barth and in recognition of former ABT corps dancer Carmen Barth. -

A Long Way from New York City: Socially Stratified Contact-Induced Phonological Convergence in Ganluo Ersu (Sichuan, China) Katia Chirkova, James Stanford, Dehe Wang

A long way from New York City: Socially stratified contact-induced phonological convergence in Ganluo Ersu (Sichuan, China) Katia Chirkova, James Stanford, Dehe Wang To cite this version: Katia Chirkova, James Stanford, Dehe Wang. A long way from New York City: Socially stratified contact-induced phonological convergence in Ganluo Ersu (Sichuan, China). Language Variation and Change, Cambridge University Press (CUP), In press. hal-01684078 HAL Id: hal-01684078 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01684078 Submitted on 15 Jan 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A long way from New York City: Socially stratified contact-induced phonological convergence in Ganluo Ersu (Sichuan, China) Authors: 1. Katia Chirkova (CNRS, France) 2. James N. Stanford (Dartmouth College, USA) 3. Dehe Wang (Xichang College, China) Corresponding author: James N. Stanford 6220 Reed Hall Dartmouth College Hanover, NH 03784 Ph. (603)646-0099 [email protected] 1 ABSTRACT Labov’s classic study, The Social Stratification of English in New York City (1966), paved the way for generations of researchers to examine sociolinguistic patterns in many different communities (Bell, Sharma, & Britain, 2016). This research paradigm has traditionally tended to focus on Western industrialized communities and large world languages and dialects, leaving many unanswered questions about lesser- studied indigenous minority communities. -

2019 YAGP KOREA Sunday, August 25, 2019

2019 YAGP KOREA Sunday, August 25, 2019 * 경연 시간은 현장 진행상황에 따라 변경될 수 있습니다. 프리 1 Open Stage 9:00-9:30 Competition 9:30-9:50 # 이름 Name Sex Title School 소속 605 신올리비아 Olivia Shinn F Blue Bird The ballet academy 더발레 아카데미 606 우수린 Su Rin Woo F I'm a Little Ballerina K-BALLET K발레(고은경발레학원) 607 전지원 Jiwon Chon F Flora IDT Tanz Academy IDT 탄츠 무용학원 608 배수현 Su-Hyeon Bae F Talisman Leewonju Ballet Academy 이원주발레아카데미 609 김초아 CHO A KIM F Coppelia Jung's Ballet Academy 정스 발레 아카데미 610 장유원 YU WON JANG F Harp Story Royalballetdance 인천로얄발레학원 611 윤하랑 HARANG YUN F Coppelia Pose ballet academy 포즈발레학원 612 김서영 Seo young KIM F Black Swan Royal ballet academy 로얄발레학원 613 이도은 DO EUN LEE F THE PHARAOH'S DAUGHTER Grand Ballet Academy 그랑발레학원 614 신올리비아 Olivia Shinn F Sky Lark The ballet academy 더발레 아카데미 615 우수린 Su Rin Woo F Cupid from Don Quixote K-BALLET K발레(고은경발레학원) 616 전지원 Jiwon Chon F The sleeping beauty Lilac Fairy IDT Tanz Academy IDT 탄츠 무용학원 617 이현수 Hyun Soo Lee M Marine Boy The ballet academy 더 발레 아카데미 618 배수현 Su-Hyeon Bae F A pleasant outing Leewonju Ballet Academy 이원주발레아카데미 프리 2 Open Stage 9:00-9:30 Competition 9:50-10:50 # 이름 Name Sex Title School 소속 508 신아라 ARA SHIN F Odalisque Variations The Ballet Academy 더발레아카데미 509 변재희 JaeHee Byun F Paquita Polonaise Sejong Miso Ballet Academy 세종미소발레학원 510 권도희 DO HEE KWON F Grand Pas Classique NEW Ballet Academy 뉴 발레아카데미 511 김채은 chae eun kim F Esmeralda Nonhyeon Bolshoi Dance Academy,Incheon 인천 논현 볼쇼이 무용학원 512 허승비 SEUNGBI HEO F Paquita Polonaise Namyangju Lausanne Ballet Academy 남양주 로잔발레아카데미 513 권서연 SEO YEON KWON F coppelia -

Gemination As Fortition?

Gemination as fortition? Articulatory data from Hungarian Maida Percival, Tamás Gábor Csapó, Márton Bartók, Andrea Deme, Tekla Etelka Gráczi, Alexandra Markó Introduction: This study uses ultrasound imaging to investigate how tongue position differs across singleton and geminate consonants in Hungarian. In previous research, coronal geminates were found to be produced with greater lingual-palatal contact and a higher and flatter tongue (Kochetov & Kang, 2017; Payne, 2006). In Eastern Oromo, ultrasound imaging found similarly results that the tongue was more advanced in the mouth for coronal geminates, suggesting that it was more fully reaching its targeted place of articulation than singletons (Percival et al., 2019). These findings liken gemination with fortition. We follow up on these studies by examining whether there is evidence of differences in lingual articulation in geminates compared to singletons in Hungarian. As previous studies concentrated on coronal stops, we additionally ask if similar patterns of tongue raising or fronting can be found for geminates at other places of articulation as this could indicate how closely the pattern is tied to gemination in general versus a tongue pull mechanism limited to coronals. Methodology: Five native speakers of Hungarian (3 female, 2 male) were recorded with ultrasound and audio in Articulate Assistant Advanced (AAA). They read six repetitions of a word list containing geminate and singleton voiced and voiceless bilabial stops, alveolar stops, alveolar fricatives, and velar stops in intervocalic (post-tonic) position. Ultrasound frames at the point of maximum constriction were selected, and tongue contours were traced in AAA. The tongue contours were rotated to the speaker’s bite plane and divided into three regions (coronal, velar, and pharyngeal) (c.f. -

On the Theoretical Implications of Cypriot Greek Initial Geminates

<LINK "mul-n*">"mul-r16">"mul-r8">"mul-r19">"mul-r14">"mul-r27">"mul-r7">"mul-r6">"mul-r17">"mul-r2">"mul-r9">"mul-r24"> <TARGET "mul" DOCINFO AUTHOR "Jennifer S. Muller"TITLE "On the theoretical implications of Cypriot Greek initial geminates"SUBJECT "JGL, Volume 3"KEYWORDS "geminates, representation, phonology, Cypriot Greek"SIZE HEIGHT "220"WIDTH "150"VOFFSET "4"> On the theoretical implications of Cypriot Greek initial geminates* Jennifer S. Muller The Ohio State University Cypriot Greek contrasts singleton and geminate consonants in word-initial position. These segments are of particular interest to phonologists since two divergent representational frameworks, moraic theory (Hayes 1989) and timing-based frameworks, including CV or X-slot theory (Clements and Keyser 1983, Levin 1985), account for the behavior of initial geminates in substantially different ways. The investigation of geminates in Cypriot Greek allows these differences to be explored. As will be demonstrated in a formal analysis of the facts, the patterning of geminates in Cypriot is best accounted for by assuming that the segments are dominated by abstract timing units such as X- or C-slots, rather than by a unit of prosodic weight such as the mora. Keywords: geminates, representation, phonology, Cypriot Greek 1. Introduction Cypriot Greek is of particular interest, not only because it is one of the few varieties of Modern Greek maintaining a consonant length contrast, but more importantly because it exhibits this contrast in word-initial position: péfti ‘Thursday’ vs. ppéfti ‘he falls’.Although word-initial geminates are less common than their word-medial counterparts, they are attested in dozens of the world’s languages in addition to Cypriot Greek. -

South Korea's Economic Engagement Toward North Korea

South Korea’s Economic Engagement toward North Korea Lee Sangkeun & Moon Chung-in 226 | Joint U.S.-Korea Academic Studies On February 10, 2016, the South Korean government announced the closure of the Gaeseong Industrial Complex, a symbol of its engagement policy and inter-Korean rapprochement. The move was part of its proactive, unilateral sanctions against North Korea’s fourth nuclear test in January and rocket launch in February.1 Pyongyang reciprocated by expelling South Korean personnel working in the industrial complex and declaring it a military control zone.2 Although the May 24, 2010 measure following the sinking of the Cheonan naval vessel significantly restricted inter-Korea exchanges and cooperation, the Seoul government spared the Gaeseong complex. With its closure, however, inter-Korean economic relations came to a complete halt, and no immediate signs of revival of Seoul’s economic engagement with the North can be detected. This chapter aims at understanding the rise and decline of this engagement with North Korea by comparing the progressive decade of Kim Dae-jung (KDJ) and Roh Moo-hyun (RMH) with the conservative era of Lee Myung-bak (LMB) and Park Geun-hye (PGH). It also looks to the future of inter-Korean relations by examining three plausible scenarios of economic engagement. Section one presents a brief overview of the genesis of Seoul’s economic engagement strategy in the early 1990s, section two examines this engagement during the progressive decade (1998-2007), and section three analyzes that of the conservative era (2008-2015). They are followed by a discussion of three possible outlooks on the future of Seoul’s economic engagement with Pyongyang. -

Consonant Gemination in Moroccan Arabic: a Constraint- Based Analysis Ayoub Noamane

Consonant Gemination in Moroccan Arabic: A Constraint- Based Analysis Ayoub Noamane To cite this version: Ayoub Noamane. Consonant Gemination in Moroccan Arabic: A Constraint- Based Analysis. Journal of Applied Language and Culture Studies, Applied Language and Culture Studies Lab (ALCS), Faculty of Letters and Humanties, Chouaib Doukkali University in El Jadida, 2020, 3, pp.37 - 68. halshs- 02546392 HAL Id: halshs-02546392 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02546392 Submitted on 7 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Journal of Applied Language and Culture Studies pISSN 2605-7506 Issue 3, 2020, pp. 37-68 e2605-7697 https://revues.imist.ma/index.php?journal=JALCS Consonant Gemination in Moroccan Arabic: A Constraint- Based Analysis1 Ayoub Noamane Mohammed V University, Rabat, Morocco To cite this article: Noamane, A. (2020). Consonant Gemination in Moroccan Arabic: A Constraint-based Analysis. Journal of Applied Language and Culture Studies, 3, 37-68. Abstract The purpose of this paper is to examine the phonological and morphological patterning of geminates in Moroccan Arabic (MA), using the constraint-based framework of Optimality Theory (Prince & Smolensky 1993/2004; McCarthy & Prince,1993a, 1993b, 1995).