MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: NETHERLANDS Mapping Digital Media: Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Paper (PDF)

Worldwide Readership Research Symposium 2007 Session 2 Paper 9 FREE NEWSPAPER READERSHIP Piet Bakker, Amsterdam School of Communications Research, University of Amsterdam Abstract Twelve years after the introduction of the first free commuter newspaper in Sweden, circulation of free newspapers has risen to 40 million daily copies. Readership of free newspapers is more complex and in many cases harder to pin down. In general it is different from readership of paid newspapers. The first difference concerns the demographics of the readers: free papers target the affluent 18 to 34 group and in many cases try to achieve that by choosing particular ways of distribution, and also by concentrating on specific content. Age, indeed seems to be significantly lower in most cases although the average readers does not seem to be particularly wealthy. The second distinct feature is the amount of unique readers of free newspaper. Results on the few available cases indicate that around half of the readers only read papers although also lower levels have been reported. The third issue concerns readers per copy. The traditional free commuter daily can reach to a rather high number of readers per copy; but with many markets reaching free newspaper saturation this number seems to be dropping, whereas free door-to-door distributed free papers and afternoon papers have a lower readership per copy. In this paper we will present information on these three issues from a dozen markets, using audited readership data. Free Newspaper Readership The World Association of Newspapers (2007) reported on the year 2006 that daily circulation of newspapers increased with 4.61 percent (25 million copies) compared to 2005. -

LILY VAN DER STOKKER Born 1954 in Den Bosch, the Netherlands Lives and Works in Amsterdam and New York

LILY VAN DER STOKKER Born 1954 in Den Bosch, the Netherlands Lives and works in Amsterdam and New York SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 Hammer Projects: Lily van der Stokker, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles 2014 Huh, Koenig & Clinton, New York Hello Chair, Air de Paris, Paris 2013 Sorry, Same Wall Painting, The New Museum, New York 2012 Living Room, Kaufmann Repetto, Milan 2011 Not so Nice, Helga Maria Klosterfelde Editions, Berlin 2010 Terrible and Ugly, Leo Koenig Inc., New York No Big Deal Thing, Tate St. Ives, Cornwall, UK (cat.) Terrible, Museum Boijmans, Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, The Netherlands Flower Floor Painting, La Conservera, Ceuti/Murcia, Spain (cat.) 2009 Dorothy & Lily fahren boot, Paris-Berlin: Air de Paris chez, Esther Schipper, Berlin 2005-07 De Zeurclub/The Complaints Club, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, the Netherlands 2005 Air de Paris, Paris Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA Family, Money, Inheritance, Galleria Francesca Kaufmann, Milan Furniture Project, Galleria Francesca Kaufmann, Milan 2004 Oom Jan en Tante Annie, one year installation in Cupola of Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht, the Netherlands (cat.) Lily van der Stokker - Wallpaintings, Feature Inc., New York, with Richard Kern Tafels en stoelen, VIVID vormgeving, Rotterdam, the Netherlands Feature Inc., New York 2003 Beauty, Friendship and Old Age, Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Arnhem, the Netherlands Small Talk, Performative Installation # 2, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany, (cat.) Easy Fun, Galerie Klosterfelde, Berlin 2002 Air de Paris, Paris, with Rob Pruitt Galleria Francesca -

TV Channel Distribution in Europe: Table of Contents

TV Channel Distribution in Europe: Table of Contents This report covers 238 international channels/networks across 152 major operators in 34 EMEA countries. From the total, 67 channels (28%) transmit in high definition (HD). The report shows the reader which international channels are carried by which operator – and which tier or package the channel appears on. The report allows for easy comparison between operators, revealing the gaps and showing the different tiers on different operators that a channel appears on. Published in September 2012, this 168-page electronically-delivered report comes in two parts: A 128-page PDF giving an executive summary, comparison tables and country-by-country detail. A 40-page excel workbook allowing you to manipulate the data between countries and by channel. Countries and operators covered: Country Operator Albania Digitalb DTT; Digitalb Satellite; Tring TV DTT; Tring TV Satellite Austria A1/Telekom Austria; Austriasat; Liwest; Salzburg; UPC; Sky Belgium Belgacom; Numericable; Telenet; VOO; Telesat; TV Vlaanderen Bulgaria Blizoo; Bulsatcom; Satellite BG; Vivacom Croatia Bnet Cable; Bnet Satellite Total TV; Digi TV; Max TV/T-HT Czech Rep CS Link; Digi TV; freeSAT (formerly UPC Direct); O2; Skylink; UPC Cable Denmark Boxer; Canal Digital; Stofa; TDC; Viasat; You See Estonia Elion nutitv; Starman; ZUUMtv; Viasat Finland Canal Digital; DNA Welho; Elisa; Plus TV; Sonera; Viasat Satellite France Bouygues Telecom; CanalSat; Numericable; Orange DSL & fiber; SFR; TNT Sat Germany Deutsche Telekom; HD+; Kabel -

Binnenwerk Engels.1997

Annual Report 1998 Distribution Paper Delivery The reader There is also a version on Internet. The address is: http://www.telegraaf.nl CONTENTS Managing Board..................................................................................................................4 Supervisory Board Members ................................................................................................. 5 Report of the Supervisory Board to the shareholders .............................................................. 6 Consolidated key figures....................................................................................................... 7 Report for the year 1998 of Stichting Administratiekantoor van aandelen N.V. Holdingmaatschappij De Telegraaf .................................................................................. 8 Declaration of Independence................................................................................................. 8 Annual Report The Company ...................................................................................................................... 9 Amsterdam operations.......................................................................................................... 17 Newspaper business............................................................................................................. 19 De Telegraaf Tijdschriften Groep ............................................................................................ 22 Audiovisual activities and electronic media ........................................................................... -

Advies-Afstemmen Op AT5-23.11-2.Indd

Afstemmen op AT5 nov ‘16 Inhoud 1. Inleiding 3 2. Historische schets 4 3. Knelpunten bij het huidige AT5 7 4. Toekomstvisie 11 5. AT5 als 14e regionale omroep 13 6. Aanbevelingen 16 I. Inhoudelijke kwaliteitsverbetering 16 II. Organisatorische kwaliteitsverbetering 17 7. Samenvatting 20 Colofon 22 Bijlage 1: Lijst van personen die door de kunstraad zijn geraadpleegd 23 Bijlage 2: De adviesaanvraag 25 Bijlage 3: Brief Raad voor Cultuur 27 Amsterdamse Afstemmen op AT5 | nov ‘16 AKr Kunstraad 1. Inleiding 1. Inleiding AT5 bestaat nu bijna 25 jaar. In die tijd is het een belangrijke speler in de plaatselijke media geworden, een kweekvijver van talent en de omroep waar Amsterdammers op afstemmen (op televisie of via sociale media) voor snelle lokale berichtgeving. AT5 heeft op die manier een belangrijke functie ingenomen in het Amsterdamse medialandschap. De geschiedenis van AT5 is echter ook moeizaam geweest, vooral op financieel gebied. De reclame-inkomsten zijn nooit groot genoeg geweest om uit de kosten te kunnen komen. De gemeente Amsterdam is vanaf het begin cofinancier van de zender geweest, maar het financiële commitment reikte doorgaans niet verder dan enkele jaren. Steeds was het de bedoeling dat de zender binnen afzienbare tijd op eigen benen zou staan. Die gewenste financiële zelfstandigheid is echter nooit haalbaar gebleken. De zender is uiteindelijk in 2012, dankzij het partnerschap met regionale omroep NH, in financieel rustiger vaarwater terechtgekomen. Sindsdien heeft ook de bijdrage van de gemeente een meer structurele vorm aangenomen. Door de verbintenis met NH is AT5, na jaren van onzekerheid, gestabiliseerd. De twee organisaties fungeren tegenwoordig in nauwe onderlinge samenhang, met een directeur en een hoofdredacteur die deze functie vervullen voor beide zenders. -

Record of Agreement

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 26.1.2010 C(2010)132 final In the published version of this decision, some information PUBLIC VERSION has been omitted, pursuant to articles 24 and 25 of Council Regulation (EC) No 659/1999 of 22 March 1999 laying WORKING LANGUAGE down detailed rules for the application of Article 93 of the EC Treaty, concerning non-disclosure of information This document is made available for covered by professional secrecy. The omissions are information purposes only. shown thus […]. Subject: State aid E 5/2005 (ex NN 170b/2003) – Annual financing of the Dutch public service broadcasters – The Netherlands Excellency, The Commission has the honour to inform you that the commitments given by the Netherlands in the context of the present procedure remove the Commission's concerns about the incompatibility of the current annual financing regime. Consequently, the Commission decided to close the present investigation. 1. PROCEDURE (1) The present case was initiated based on a number of complaints. (2) On 24 May 2002 the Commission received a complaint from CLT-UFA S.A. and its associated subsidiaries RTL/de Holland Media Groep S.A. and Yorin tv BV regarding the financing of Dutch public broadcasters. On 10 October 2002 and 28 November 2002 SBS Broadcasting and VESTRA1, the association of commercial broadcasters in the Netherlands, each submitted complaints. VESTRA also submitted further information in the course of the investigation. On 3 June 2003 NDP, the Dutch Newspaper Publishers Association, submitted a complaint on behalf of its members. On 19 June 2003 the publishing company De Telegraaf lodged a complaint. -

Digital News Report 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 2 2 / 3

1 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 2 2 / 3 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, David A. L. Levy and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 4 Contents Foreword by David A. L. Levy 5 3.12 Hungary 84 Methodology 6 3.13 Ireland 86 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.14 Italy 88 3.15 Netherlands 90 SECTION 1 3.16 Norway 92 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 8 3.17 Poland 94 3.18 Portugal 96 SECTION 2 3.19 Romania 98 Further Analysis and International Comparison 32 3.20 Slovakia 100 2.1 The Impact of Greater News Literacy 34 3.21 Spain 102 2.2 Misinformation and Disinformation Unpacked 38 3.22 Sweden 104 2.3 Which Brands do we Trust and Why? 42 3.23 Switzerland 106 2.4 Who Uses Alternative and Partisan News Brands? 45 3.24 Turkey 108 2.5 Donations & Crowdfunding: an Emerging Opportunity? 49 Americas 2.6 The Rise of Messaging Apps for News 52 3.25 United States 112 2.7 Podcasts and New Audio Strategies 55 3.26 Argentina 114 3.27 Brazil 116 SECTION 3 3.28 Canada 118 Analysis by Country 58 3.29 Chile 120 Europe 3.30 Mexico 122 3.01 United Kingdom 62 Asia Pacific 3.02 Austria 64 3.31 Australia 126 3.03 Belgium 66 3.32 Hong Kong 128 3.04 Bulgaria 68 3.33 Japan 130 3.05 Croatia 70 3.34 Malaysia 132 3.06 Czech Republic 72 3.35 Singapore 134 3.07 Denmark 74 3.36 South Korea 136 3.08 Finland 76 3.37 Taiwan 138 3.09 France 78 3.10 Germany 80 SECTION 4 3.11 Greece 82 Postscript and Further Reading 140 4 / 5 Foreword Dr David A. -

The Agency Makes the (Online) News World Go Round: the Impact of News Agency Content on Print and Online News

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The agency makes the (online) news world go round: The impact of news agency content on print and online news Boumans, J.; Trilling, D.; Vliegenthart, R.; Boomgaarden, H. Publication date 2018 Document Version Final published version Published in International Journal of Communication : IJoC License CC BY-NC-ND Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Boumans, J., Trilling, D., Vliegenthart, R., & Boomgaarden, H. (2018). The agency makes the (online) news world go round: The impact of news agency content on print and online news. International Journal of Communication : IJoC, 12, 1768-1789. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/7109 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library -

Football Clubs, City Images and Cultural Differentiation: Identifying with Rivalling Vitesse Arnhem and NEC Nijmegen

Urban History, 46, 2 (2019) © The Author(s) 2018. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/S0963926818000354 First published online 29 May 2018 Football clubs, city images and cultural differentiation: identifying with rivalling Vitesse Arnhem and NEC Nijmegen ∗ JON VERRIET Sports History Research Group, History Department, Radboud University Nijmegen, Erasmusplein 1, 6525 HT Nijmegen, The Netherlands abstract: How are deep relationships between city and club identification formed, and are they inevitable? The aim of this article is to provide a historical analysis of the rivalry between two football clubs, Vitesse Arnhem and NEC Nijmegen, explicating their various ‘axes of enmity’. Supporters, club officials and observers of these two clubs created and selectively maintained similarities between respective city image and club image. The process of ‘othering’ influenced both city and club images and helped create oppositional identities. Herein, football identification reflects broader societal needs for a place-based identity, and for a coherent image of both self and other. Introduction The history of sport has proved a fruitful field for research into processes of identification. According to Jeff Hill, the texts and practices of sports represent ‘structured habits of thought and behaviour which contribute to our ways of seeing ourselves and others’.1 Sports rivalries in particular have received attention from sociologists and historians, as they allow investigations into community bonding and the process of ‘othering’. -

Inkomend Gescand Document 1-10-2009

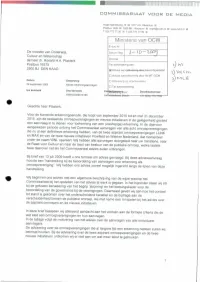

COMMISSARIAAT VOOR DE MEDIA Hoge Naarderweg 78 HUI 1217 AH Hilversum HUI Postbus 1426 HUI 1200 BK Hilversum HUI [email protected] HUI www.cvdm.nl T 035 773 77 00 Ulli F 035 773 77 99 Hill Ministerie van OCW E-doc Nr. De minister van Onderwijs, Datum Reg l-IQ-loo^ Cultuur en Wetenschap de heer dr. Ronald H.A. Plasterk Directie Postbus 16375 Ter behandeling aan: 2500 BJ DEN HAAG B'Advies aan/jildoening dmot bewindspersoon D Advies aan/afdoening door lid MT-OCW Datum Onderwerp D Afdoening op directieniveau 29 september 2009 Advies erkenningaanvragen G Ter kennisneming Uw kenmerk Ons kenmerk Col fcfttóSfilftpOoor; Doorkiesnummer 18895/2009014195 JariVoccolmon Boseh i 31 (005) 773 TT09 Geachte heer Plasterk, Voor de komende erkenningperiode, die loopt van september 2010 tot en met 31 december 2015, zijn de bestaande omroepverenigingen en nieuwe initiatieven in de gelegenheid gesteld een aanvraag in te dienen voor toekenning van een (voorlopige) erkenning. In de daarvoor aangewezen periode ontving het Commissariaat aanvragen van alle acht omroepverenigingen die nu al een definitieve erkenning hebben, van de twee aspirant omroepverenigingen LLiNK en MAX en van de twee nieuwe initiatieven PowNed en Wakker Nederland, dat momenteel onder de naam WNL opereert. Wij hebben alle aanvragen doorgeleid naar uw ministerie, naar de Raad voor Cultuur en naar de raad van bestuur van de publieke omroep, welke laatste twee daarover net als het Commissariaat advies zullen uitbrengen. Bij brief van 13 juli 2009 heeft u ons formeel om advies gevraagd. Bij deze adviesaanvraag hoorde een "handreiking bij de beoordeling van aanvragen voor erkenning als omroepvereniging". -

Framing of Corporate Crises in Dutch Newspaper Articles

Framing of corporate crises in Dutch newspaper articles A corpus study on crisis response strategies, quotation, and metaphorical frames T.J.A. Haak Radboud University Date of issue: 20 December 2019 Supervisor: Dr. W.G. Reijnierse Second Assessor: Dr. U. Nederstigt Program: MA International Business Communication Framing of corporate crises in Dutch media Abstract Research topic - The purpose of this study was to find answers to how corporate crises are framed in Dutch media. A journalist frames a crisis by making choices about information, quotation, and language. This thesis focusses on these aspects by analysing what crisis response strategies can be found, and how this information is reported by the journalist using quotation and metaphor. Hypotheses and research – It was expected that a company’s cultural background would influence the crisis response strategy that is reported in the newspapers. The hypotheses stated that companies originating from countries with an individualistic culture appear in newspapers more often with a diminish strategy and less often with a no response or rebuild strategy than companies originating from countries with a collectivistic culture. The denial strategy was expected to appear equally frequent. Furthermore, it was studied whether a link exists between these crisis response strategies and the occurrence of quotes and metaphors within Dutch newspaper articles. Method – These topics were studied using a combination of quantitative and qualitative research methods. A corpus of Dutch newspaper articles (N = 606) covering corporate crises was analysed. Findings – No significant relation was found between the reported crisis response strategies and companies’ cultural backgrounds (individualistic or collectivistic). A relationship was found between the reported crisis response strategy and (in)direct quotation of the company in crisis. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Passie of professie. Galeries en kunsthandel in Nederland Gubbels, T. Publication date 1999 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Gubbels, T. (1999). Passie of professie. Galeries en kunsthandel in Nederland. Uniepers. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:25 Sep 2021 Adrichem (1991) ASK als beleidsinstrument (1978) Bibliografie J. van Adrichem, Het Rotterdams ASK als beleidsinstrument. In: kunstklimaat: particulier initiatief en Informatiebulletin Raad voor de Kunst, Boeken, rapporten en tijdschrift overheidsbeleid. In: J.C Dagevos, P.C. 1978 (juni) nr. 6. artikelen van Druenen, P. Th. van der Laat (red.) Kunst-zaken: particulier initiatief en Beek (1988) Abbing(1998) overheidsbeleid in de wereld van de A. Beek, Le Canard: cultureel trefpunt H.