Entropy and Art: Essay on Disorder and Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Order and Disorder: Poetics of Exception

Order and disorder Página 1 de 19 Daniel Innerarity Order and disorder: Poetics of exception “While working, the mind proceeds from disorder to order. It is important that it maintain resources of disorder until the end, and that the order it has begun to impose on itself does not bind it so completely, does not become such a rigid master, that it cannot change it and make use of its initial liberty” (Paul Valéry 1960, 714). We live at a time when nothing is conquered with absolute security, neither knowledge nor skills. Newness, the ephemeral, the rapid turn-over of information, of products, of behavioral models, the need for frequent adaptations, the demand for flexibility, all give the impression that we live only in the present in a way that hinders stabilization. Imprinting something onto the long term seems less important that valuing the instant and the event. That being said, thought has always been connected to the task of organizing and classifying, with the goal of conferring stability on the disorganized multiplicity of the manifestations of reality. In order to continue making sense, this articulation of the disparate must understand the paradoxes of order and organization. That is what has been going on recently: there has been a greater awareness of disorder and irregularity at the level of concepts and models for action and in everything from science to the theory of organizations. This difficulty is as theoretical as it is practical; it demands that we reconsider disorder in all its manifestations, as disorganization, turbulence, chaos, complexity, or entropy. -

![Arxiv:1212.0736V1 [Cond-Mat.Str-El] 4 Dec 2012 Non-Degenerate Polarized Phase](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3308/arxiv-1212-0736v1-cond-mat-str-el-4-dec-2012-non-degenerate-polarized-phase-123308.webp)

Arxiv:1212.0736V1 [Cond-Mat.Str-El] 4 Dec 2012 Non-Degenerate Polarized Phase

Disorder by disorder and flat bands in the kagome transverse field Ising model M. Powalski,1 K. Coester,1 R. Moessner,2 and K. P. Schmidt1, ∗ 1Lehrstuhl f¨urTheoretische Physik 1, TU Dortmund, Germany 2Max Planck Institut f¨urkomplexe Systeme, D-01187 Dresden, Germany (Dated: August 10, 2018) We study the transverse field Ising model on a kagome and a triangular lattice using high-order series expansions about the high-field limit. For the triangular lattice our results confirm a second- order quantum phase transition in the 3d XY universality class. Our findings for the kagome lattice indicate a notable instance of a disorder by disorder scenario in two dimensions. The latter follows from a combined analysis of the elementary gap in the high- and low-field limit which is shown to stay finite for all fields h. Furthermore, the lowest one-particle dispersion for the kagome lattice is extremely flat acquiring a dispersion only from order eight in the 1=h limit. This behaviour can be traced back to the existence of local modes and their breakdown which is understood intuitively via the linked cluster expansion. PACS numbers: 75.10.Jm, 05.30.Rt, 05.50.+q,75.10.-b I. INTRODUCTION for arbitrary transverse fields providing a novel instance of disorder by disorder in which quantum fluctuations The interplay of geometric frustration and quantum select a quantum disordered state out of the classically fluctuations in magnetic systems provides a fascinating disordered ground-state manifold. There is no conclu- field of research. It gives rise to a multitude of quan- sive evidence excluding a possible ordering of the kagome tum phases manifesting novel phenomena of quantum transverse field Ising model (TFIM) and its global phase order and disorder, featuring prominent examples such diagram remains unsettled. -

Order and Disorder in Liquid-Crystalline Elastomers

Adv Polym Sci (2012) 250: 187–234 DOI: 10.1007/12_2010_105 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2011 Published online: 3 December 2010 Order and Disorder in Liquid-Crystalline Elastomers Wim H. de Jeu and Boris I. Ostrovskii Abstract Order and frustration play an important role in liquid-crystalline polymer networks (elastomers). The first part of this review is concerned with elastomers in the nematic state and starts with a discussion of nematic polymers, the properties of which are strongly determined by the anisotropy of the polymer backbone. Neutron scattering and X-ray measurements provide the basis for a description of their conformation and chain anisotropy. In nematic elastomers, the macroscopic shape is determined by the anisotropy of the polymer backbone in combination with the elastic response of elastomer network. The second part of the review concentrates on smectic liquid-crystalline systems that show quasi-long-range order of the smectic layers (positional correlations that decay algebraically). In smectic elasto- mers, the smectic layers cannot move easily across the crosslinking points where the polymer backbone is attached. Consequently, layer displacement fluctuations are suppressed, which effectively stabilizes the one-dimensional periodic layer structure and under certain circumstances can reinstate true long-range order. On the other hand, the crosslinks provide a random network of defects that could destroy the smectic order. Thus, in smectic elastomers there exist two opposing tendencies: the suppression of layer displacement fluctuations that enhances trans- lational order, and the effect of random disorder that leads to a highly frustrated equilibrium state. These effects can be investigated with high-resolution X-ray diffraction and are discussed in some detail for smectic elastomers of different topology. -

Calculating the Configurational Entropy of a Landscape Mosaic

Landscape Ecol (2016) 31:481–489 DOI 10.1007/s10980-015-0305-2 PERSPECTIVE Calculating the configurational entropy of a landscape mosaic Samuel A. Cushman Received: 15 August 2014 / Accepted: 29 October 2015 / Published online: 7 November 2015 Ó Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht (outside the USA) 2015 Abstract of classes and proportionality can be arranged (mi- Background Applications of entropy and the second crostates) that produce the observed amount of total law of thermodynamics in landscape ecology are rare edge (macrostate). and poorly developed. This is a fundamental limitation given the centrally important role the second law plays Keywords Entropy Á Landscape Á Configuration Á in all physical and biological processes. A critical first Composition Á Thermodynamics step to exploring the utility of thermodynamics in landscape ecology is to define the configurational entropy of a landscape mosaic. In this paper I attempt to link landscape ecology to the second law of Introduction thermodynamics and the entropy concept by showing how the configurational entropy of a landscape mosaic Entropy and the second law of thermodynamics are may be calculated. central organizing principles of nature, but are poorly Result I begin by drawing parallels between the developed and integrated in the landscape ecology configuration of a categorical landscape mosaic and literature (but see Li 2000, 2002; Vranken et al. 2014). the mixing of ideal gases. I propose that the idea of the Descriptions of landscape patterns, processes of thermodynamic microstate can be expressed as unique landscape change, and propagation of pattern-process configurations of a landscape mosaic, and posit that relationships across scale and through time are all the landscape metric Total Edge length is an effective governed and constrained by the second law of measure of configuration for purposes of calculating thermodynamics (Cushman 2015). -

Order and Disorder in Nature- G

DEVELOPMENT OF PHYSICS-Order And Disorder In Nature- G. Takeda ORDER AND DISORDER IN NATURE G. Takeda The University of Tokyo and Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan Keywords:order,disorder,entropy,fluctuation,phasetransition,latent heat, phase diagram, critical point, free energy, spontaneous symmetry breaking, open system, convection current, Bernard cell, crystalline solid, lattice structure, lattice vibration, phonon, magnetization, Curie point, ferro-paramagnetic transition, magnon, correlation function, correlation length, order parameter, critical exponent, renormalization group method, non-equilibrium process, Navier-Stokes equation, Reynold number, Rayleigh number, Prandtl number, turbulent flow, Lorentz model, laser. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Structure of Solids and Liquids 2.1.Crystalline Structure of Solids 2.2.Liquids 3. Phase Transitions and Spontaneous Broken Symmetry 3.1.Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking 3.2.Order Parameter 4. Non-equilibrium Processes Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical Skectch Summary Order-disorder problems are a rapidly developing subject not only in physics but also in all branches of science. Entropy is related to the degree of order in the structure of a system, and the second law of thermodynamics states that the system should change from a more ordered state to a less ordered one as long as the system is isolated from its surroundings.UNESCO – EOLSS Phase transitions of matter are the most well studied order-disorder transitions and occur at certain fixed values of dynamical variables such as temperature and pressure. In general, the degreeSAMPLE of order of the atomic orCHAPTERS molecular arrangement in matter will change by a phase transition and the phase at lower temperature than the transition temperature is more ordered than that at higher temperature. -

DMAAC – February 1973

LUNAR TOPOGRAPHIC ORTHOPHOTOMAP (LTO) AND LUNAR ORTHOPHOTMAP (LO) SERIES (Published by DMATC) Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Scale: 1:250,000 Projection: Transverse Mercator Sheet Size: 25.5”x 26.5” The Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Series are the first comprehensive and continuous mapping to be accomplished from Apollo Mission 15-17 mapping photographs. This series is also the first major effort to apply recent advances in orthophotography to lunar mapping. Presently developed maps of this series were designed to support initial lunar scientific investigations primarily employing results of Apollo Mission 15-17 data. Individual maps of this series cover 4 degrees of lunar latitude and 5 degrees of lunar longitude consisting of 1/16 of the area of a 1:1,000,000 scale Lunar Astronautical Chart (LAC) (Section 4.2.1). Their apha-numeric identification (example – LTO38B1) consists of the designator LTO for topographic orthophoto editions or LO for orthophoto editions followed by the LAC number in which they fall, followed by an A, B, C or D designator defining the pertinent LAC quadrant and a 1, 2, 3, or 4 designator defining the specific sub-quadrant actually covered. The following designation (250) identifies the sheets as being at 1:250,000 scale. The LTO editions display 100-meter contours, 50-meter supplemental contours and spot elevations in a red overprint to the base, which is lithographed in black and white. LO editions are identical except that all relief information is omitted and selenographic graticule is restricted to border ticks, presenting an umencumbered view of lunar features imaged by the photographic base. -

Equilibrium Phases of Dipolar Lattice Bosons in the Presence of Random Diagonal Disorder

Equilibrium phases of dipolar lattice bosons in the presence of random diagonal disorder C. Zhang,1 A. Safavi-Naini,2 and B. Capogrosso-Sansone3 1Homer L. Dodge Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma ,73019, USA 2JILA , NIST and Department of Physics, University of Colorado, 440 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309, USA 3Department of Physics, Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, 01610, USA Ultracold gases offer an unprecedented opportunity to engineer disorder and interactions in a controlled manner. In an effort to understand the interplay between disorder, dipolar interaction and quantum degeneracy, we study two-dimensional hard-core dipolar lattice bosons in the presence of on-site bound disorder. Our results are based on large-scale path-integral quantum Monte Carlo simulations by the Worm algorithm. We study the ground state phase diagram at fixed half-integer filling factor for which the clean system is either a superfluid at lower dipolar interaction strength or a checkerboard solid at larger dipolar interaction strength. We find that, even for weak dipolar interaction, superfluidity is destroyed in favor of a Bose glass at relatively low disorder strength. Interestingly, in the presence of disorder, superfluidity persists for values of dipolar interaction strength for which the clean system is a checkerboard solid. At fixed disorder strength, as the dipolar interaction is increased, superfluidity is destroyed in favor of a Bose glass. As the interaction is further increased, the system eventually develops extended checkerboard patterns in the density distribution. Due to the presence of disorder, though, grain boundaries and defects, responsible for a finite residual compressibility, are present in the density distribution. -

Entropy (Order and Disorder)

Entropy (order and disorder) Locally, the entropy can be lowered by external action. This applies to machines, such as a refrigerator, where the entropy in the cold chamber is being reduced, and to living organisms. This local decrease in entropy is, how- ever, only possible at the expense of an entropy increase in the surroundings. 1 History This “molecular ordering” entropy perspective traces its origins to molecular movement interpretations developed by Rudolf Clausius in the 1850s, particularly with his 1862 visual conception of molecular disgregation. Sim- ilarly, in 1859, after reading a paper on the diffusion of molecules by Clausius, Scottish physicist James Clerk Boltzmann’s molecules (1896) shown at a “rest position” in a solid Maxwell formulated the Maxwell distribution of molec- ular velocities, which gave the proportion of molecules having a certain velocity in a specific range. This was the In thermodynamics, entropy is commonly associated first-ever statistical law in physics.[3] with the amount of order, disorder, or chaos in a thermodynamic system. This stems from Rudolf Clau- In 1864, Ludwig Boltzmann, a young student in Vienna, sius' 1862 assertion that any thermodynamic process al- came across Maxwell’s paper and was so inspired by it ways “admits to being reduced to the alteration in some that he spent much of his long and distinguished life de- way or another of the arrangement of the constituent parts veloping the subject further. Later, Boltzmann, in efforts of the working body" and that internal work associated to develop a kinetic theory for the behavior of a gas, ap- with these alterations is quantified energetically by a mea- plied the laws of probability to Maxwell’s and Clausius’ sure of “entropy” change, according to the following dif- molecular interpretation of entropy so to begin to inter- ferential expression:[1] pret entropy in terms of order and disorder. -

REVIEW Theory of Displacive Phase Transitions in Minerals

American Mineralogist, Volume 82, pages 213±244, 1997 REVIEW Theory of displacive phase transitions in minerals MARTIN T. DOVE Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EQ, U.K. ABSTRACT A lattice-dynamical treatment of displacive phase transitions leads naturally to the soft- mode model, in which the phase-transition mechanism involves a phonon frequency that falls to zero at the transition temperature. The basic ideas of this approach are reviewed in relation to displacive phase transitions in silicates. A simple free-energy model is used to demonstrate that Landau theory gives a good approximation to the free energy of the transition, provided that the entropy is primarily produced by the phonons rather than any con®gurational disorder. The ``rigid unit mode'' model provides a physical link between the theory and the chemical bonds in silicates and this allows us to understand the origin of the transition temperature and also validates the application of the soft-mode model. The model is also used to reappraise the nature of the structures of high-temperature phases. Several issues that remain open, such as the origin of ®rst-order phase transitions and the thermodynamics of pressure-induced phase transitions, are discussed. INTRODUCTION represented in Figure 1. In each case, the phase transitions involve small translations and rotations of the (Si,Al)O The study of phase transitions extends back a century 4 tetrahedra. One of the most popular of the new devel- to the early work on quartz, ferromagnets, and liquid-gas opments in the theory of displacive phase transitions in phase equilibrium. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

Biochemical Thermodynamics

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CHAPTER 1 Biochemical Thermodynamics Learning Objectives 1. Defi ne and use correctly the terms system, closed, open, surroundings, state, energy, temperature, thermal energy, irreversible process, entropy, free energy, electromotive force (emf), Faraday constant, equilibrium constant, acid dissociation constant, standard state, and biochemical standard state. 2. State and appropriately use equations relating the free energy change of reactions, the standard-state free energy change, the equilibrium constant, and the concentrations of reactants and products. 3. Explain qualitatively and quantitatively how unfavorable reactions may occur at the expense of a favorable reaction. 4. Apply the concept of coupled reactions and the thermodynamic additivity of free energy changes to calculate overall free energy changes and shifts in the concentrations of reactants and products. 5. Construct balanced reduction–oxidation reactions, using half-reactions, and calculate the resulting changes in free energy and emf. 6. Explain differences between the standard-state convention used by chemists and that used by biochemists, and give reasons for the differences. 7. Recognize and apply correctly common biochemical conventions in writing biochemical reactions. Basic Quantities and Concepts Thermodynamics is a system of thinking about interconnections of heat, work, and matter in natural processes like heating and cooling materials, mixing and separation of materials, and— of particular interest here—chemical reactions. Thermodynamic concepts are freely used throughout biochemistry to explain or rationalize chains of chemical transformations, as well as their connections to physical and biological processes such as locomotion or reproduction, the generation of fever, the effects of starvation or malnutrition, and more. -

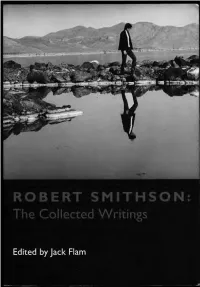

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) .