Subjective Narration in Comics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Algerian War of Independence in Algerian bande dessin�e Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2tk6g7bg Author Dean, Veronica Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Algerian War of Independence in Algerian bande dessinée A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies by Veronica Katherine Dean 2020 Copyright by Veronica Katherine Dean 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Algerian War of Independence in Algerian bande dessinée by Veronica Katherine Dean Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2020 Professor Lia N. Brozgal, Chair “The Algerian War of Independence in Algerian bande dessinée” is animated by the question of how bande dessinée from Algeria represent the nation’s struggle for independence from France. Although the war is represented extensively in bande dessinée from France and Algeria, French texts are more well-known than their Algerian counterparts among scholars and bédéphiles alike. Catalysts behind this project are the disproportionate awareness and study of French bande dessinée on the war and the fact that critical studies of Algerian bande dessinée are rare and often superficial. This project nevertheless builds upon existing scholarship by problematizing its assumptions and conclusions, including the generalization that Algerian bande dessinée that depict the war are in essence propagandistic in nature. Employing tools of comics analysis and inflecting my research with journalistic work coming out of Algeria, this project attempts to rectify the treatment of Algerian bande dessinée in critical scholarship by illustrating ii the rich tradition of historical representation in the medium. -

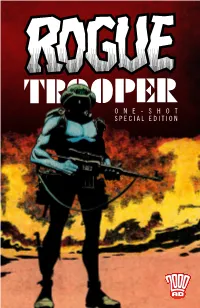

One-Shot Special Edition Script Gerry Finley-Day Guy Adams Art Dave Gibbons Darren Douglas Lee Carter Letters Simon Bowland Dave Gibbons

ONE-SHOT SPECIAL EDITION SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY GUY ADAMS ART DAVE GIBBONS DARREN DOUGLAS LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND DAVE GIBBONS REBELLION Creative Director and CEO Junior Graphic Novels Editor JASON KINGSLEY OLIVER BALL Chief Technical Officer Graphic Design CHRIS KINGSLEY SAM GRETTON, OZ OSBORNE & MAZ SMITH Head of Books & Comics Reprographics BEN SMITH JOSEPH MORGAN 2000 AD Editor in Chief PR & Marketing MATT SMITH MICHAEL MOLCHER Graphic Novels Editor Publishing Assistant KEITH RICHARDSON OWEN JOHNSON Rogue Trooper Published by Rebellion, Riverside House, Osney Mead, Oxford OX2 0ES. All contents © 1981, 2014, 2015, 2018 Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. All rights reserved. Rogue Trooper is a trademark of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. Reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form or by any means in whole or part without prior permission of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. is strictly forbidden. No similarity between any of the fictional names, characters, persons and/or institutions herein with those of any living or dead persons or institutions is intended (except for satirical purposes) and any such similarity is purely coincidental. ROGUE TROOPER SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY ART DAVE GIBBONS LETTERS DAVE GIBBONS ROGUE TROOPER DREGS OF WAR SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE FEAST SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE DEATH OF A DEMON SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND THE END ROGUE TROOPER GRAPHIC NOVELS FROM 2000 AD ROGUE TROOPER ROGUE -

Club Add 2 Page Designoct07.Pub

H M. ADVS. HULK V. 1 collects #1-4, $7 H M. ADVS FF V. 7 SILVER SURFER collects #25-28, $7 H IRR. ANT-MAN V. 2 DIGEST collects #7-12,, $10 H POWERS DEF. HC V. 2 H ULT FF V. 9 SILVER SURFER collects #12-24, $30 collects #42-46, $14 H C RIMINAL V. 2 LAWLESS H ULTIMATE VISON TP collects #6-10, $15 collects #0-5, $15 H SPIDEY FAMILY UNTOLD TALES H UNCLE X-MEN EXTREMISTS collects Spidey Family $5 collects #487-491, $14 Cut (Original Graphic Novel) H AVENGERS BIZARRE ADVS H X-MEN MARAUDERS TP The latest addition to the Dark Horse horror line is this chilling OGN from writer and collects Marvel Advs. Avengers, $5 collects #200-204, $15 Mike Richardson (The Secret). 20-something Meagan Walters regains consciousness H H NEW X-MEN v5 and finds herself locked in an empty room of an old house. She's bleeding from the IRON MAN HULK back of her head, and has no memory of where the wound came from-she'd been at a collects Marvel Advs.. Hulk & Tony , $5 collects #37-43, $18 club with some friends . left angrily . was she abducted? H SPIDEY BLACK COSTUME H NEW EXCALIBUR V. 3 ETERNITY collects Back in Black $5 collects #16-24, $25 (on-going) H The End League H X-MEN 1ST CLASS TOMORROW NOVA V. 1 ANNIHILATION A thematic merging of The Lord of the Rings and Watchmen, The End League follows collects #1-8, $5 collects #1-7, $18 a cast of the last remaining supermen and women as they embark on a desperate and H SPIDEY POWER PACK H HEROES FOR HIRE V. -

|||GET||| Superheroes and American Self Image 1St Edition

SUPERHEROES AND AMERICAN SELF IMAGE 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Michael Goodrum | 9781317048404 | | | | | Art Spiegelman: golden age superheroes were shaped by the rise of fascism International fascism again looms large how quickly we humans forget — study these golden age Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition hard, boys and girls! Retrieved June 20, Justice Society of America vol. Wonder Comics 1. One of the ways they showed their disdain was through mass comic burnings, which Hajdu discusses Alysia Yeoha supporting character created by writer Gail Simone for the Batgirl ongoing series published by DC Comics, received substantial media attention in for being the first major transgender character written in a contemporary context in a mainstream American comic book. These sound effects, on page and screen alike, are unmistakable: splash art of brightly-colored, enormous block letters that practically shout to the audience for attention. World's Fair Comics 1. For example, Black Panther, first introduced inspent years as a recurring hero in Fantastic Four Goodrum ; Howe Achilles Warkiller. The dark Skull Man manga would later get a television adaptation and underwent drastic changes. The Senate committee had comic writers panicking. Howe, Marvel Comics Kurt BusiekMark Bagley. During this era DC introduced the Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition of Batwoman inSupergirlMiss Arrowetteand Bat-Girl ; all female derivatives of established male superheroes. By format Comic books Comic strips Manga magazines Webcomics. The Greatest American Hero. Seme and uke. Len StrazewskiMike Parobeck. This era saw the debut of one of the earliest female superheroes, writer-artist Fletcher Hanks 's character Fantomahan ageless ancient Egyptian woman in the modern day who could transform into a skull-faced creature with superpowers to fight evil; she debuted in Fiction House 's Jungle Comic 2 Feb. -

Rohaidah Kamaruddin, Muhammad Nur Akmal Rosli, Minah Mohammed Salleh, Zuraini Seruji, Sharil Nizam Sha’Ri, Veeramohan Veeraputhran & Manimangai Mani

PJAEE, 17(9) (2020) Retorik Penceritaan Dalam HikayatMerong Mahawangsa Narrative Rhetorical in Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa Rohaidah Kamaruddin, Muhammad Nur Akmal Rosli, Minah Mohammed Salleh, Zuraini Seruji, Sharil Nizam Sha’ri, Veeramohan Veeraputhran & Manimangai Mani email: [email protected] Rohaidah Kamaruddin, Muhammad Nur Akmal Rosli, Minah Mohammed Salleh, Zuraini Seruji, Sharil Nizam Sha’ri, Veeramohan Veeraputhran & Manimangai Mani, Retorik Penceritaan Dalam HikayatMerong MahawangsaNarrative Rhetorical in Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa– Palarch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 17(9) (2020),ISSN 1567-214X. Keywords: Narrative rhetorical; rhetoric in hikayat; Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa Abstrack Retorik adalah seni pemakaian bahasa yang menarik, indah dan estetik. Selain itu, retorik juga merujuk kepada penggunaan bahasa yang berketerampilan, sopan dan berkesan dalam berkomunikasi. Penerapan retorik dalam sesuatu penulisan atau percakapan adalah untuk memujuk atau mempengaruhi khalayak. Dalam kajian ini, pengkaji ini mengkaji tentang penggunaan retorik dalam Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa. Objektif kajian ini adalah untuk membincangkan teknik retorik peceritaan dan kekerapan penggunaannya dalam Bab IV, Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa berdasarkan Teori Retorik Moden (1993). Kajian ini dilaksanakan berpandukan Teori Retorik Moden (1993) oleh Enos & Brown. Bahan kajian yang digunakan dalam kajian ini adalah sebuah buku hikayat Melayu yang diperkenalkan oleh Siti Hawa Haji Salleh (1998) iaitu Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa. Namun, kajian ini memfokuskan kepada satu bab sahaja dalam Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa iaitu Kisah Pengislaman Maharaja Derbar Raja II dan pengumpulan data bagi kajian ini adalah melalui kaedah analisis teks. Sehubungan dengan itu, keputusan kajian ini menunjukkan bahawa penulis Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa telah mengaplikasikan teknik retorik penceritaan seperti teknik situasi atau peristiwa, dialog, monolog, imbas kembali dan latar tempat dan masyarakat. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Bibliotherapy and Graphic Medicine

This is a preprint of a chapter accepted for publication by Facet Publishing. This extract has been taken from the author’s original manuscript and has not been edited. The definitive version of this piece may be found in Bibliotherapy, Facet, London, ISBN 9781783302410, which can be purchased from http://www.facetpublishing.co.uk/title.php?id=303410&category_code=37#.W0xzl4eoulI. The author agrees not to update the preprint or replace it with the published version of the chapter. Our titles have wide appeal across the UK and internationally and we are keen to see our authors content translated into foreign languages and welcome requests from publishers. World rights for translation are available for many of our titles. To date our books have been translated into over 25 languages. Bibliotherapy and graphic medicine Sarah McNicol, Manchester Metropolitan University 1. Introduction While most bibliotherapy activities focus on the use of written text, whether in the form of novels, poetry or self-help books, in recent years there has been a growing interest in the use of graphic novels and comics as a mode of bibliotherapy. The term ‘graphic narratives’ is used in this chapter to include both graphic novels and shorter comics in both print and digital formats. The chapter explores the ways in which graphic narratives of various types might be used as an effective form of bibliotherapy. It considers how the medium can be particularly effective in supporting important features of bibliotherapy such as providing reassurance; connection with others; alternative perspectives; and models of identity. It then draws on examples of bibliotherapy collections from different library settings to demonstrate some of the ways in which graphic narratives are currently used in bibliotherapy practice, or might have potential to be used in the future. -

Super Satan: Milton’S Devil in Contemporary Comics

Super Satan: Milton’s Devil in Contemporary Comics By Shereen Siwpersad A Thesis Submitted to Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MA English Literary Studies July, 2014, Leiden, the Netherlands First Reader: Dr. J.F.D. van Dijkhuizen Second Reader: Dr. E.J. van Leeuwen Date: 1 July 2014 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………... 1 - 5 1. Milton’s Satan as the modern superhero in comics ……………………………….. 6 1.1 The conventions of mission, powers and identity ………………………... 6 1.2 The history of the modern superhero ……………………………………... 7 1.3 Religion and the Miltonic Satan in comics ……………………………….. 8 1.4 Mission, powers and identity in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost …………. 8 - 12 1.5 Authority, defiance and the Miltonic Satan in comics …………………… 12 - 15 1.6 The human Satan in comics ……………………………………………… 15 - 17 2. Ambiguous representations of Milton’s Satan in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost ... 18 2.1 Visual representations of the heroic Satan ……………………………….. 18 - 20 2.2 Symbolic colors and black gutters ……………………………………….. 20 - 23 2.3 Orlando’s representation of the meteor simile …………………………… 23 2.4 Ambiguous linguistic representations of Satan …………………………... 24 - 25 2.5 Ambiguity and discrepancy between linguistic and visual codes ………... 25 - 26 3. Lucifer Morningstar: Obedience, authority and nihilism …………………………. 27 3.1 Lucifer’s rejection of authority ………………………..…………………. 27 - 32 3.2 The absence of a theodicy ………………………………………………... 32 - 35 3.3 Carey’s flawed and amoral God ………………………………………….. 35 - 36 3.4 The implications of existential and metaphysical nihilism ……………….. 36 - 41 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………. 42 - 46 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.1 ……………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.2 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.3 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.4 ………………………………………………………………………. -

STAR Writing 2018

STAR Writing Assessment Indicators Year 1 Emerging Developing Securing May discuss what their writing is (going to With support can say out loud what they are Can say out loud what they are going to be) about when prompted by an adult. going to write about. write about. With prompting, orally rehearses sentences Plan before writing. Orally rehearses sentences before writing. Begins to sequence sentences to form short Writes some recognisable words and Writes meaningful words, phrases and narratives for some different purposes, even phrases about their own experiences. statements about their own experiences. though the form may not always be maintained. Begins to sequence sentences into Writing can be read without requiring Writing may require some mediation. narratives, although occasionally mediation Draft mediation by the child. may be required in some writing. Uses some words, phrases and single-clause Uses mainly single and co-ordinating multi- Composition sentences. clause sentences. May use adjectives to describe the size or colour of an object. Can identify if writing makes sense when it is Reads their writing back to an adult, with Reads back their writing clearly to an adult reread by an adult, and with support and support and when prompted. or their peers. suggestions may make improvements. Can identify if writing makes sense, although Evaluate Can identify if writing makes sense and starts they may rely upon an adult to suggest to suggest improvements with prompting. improvements. Adds suffixes to verbs where no change is Uses regular plural noun suffixes –s, e.g. dog, Uses regular plural noun suffixes –s or –es, in needed to the root word (e.g. -

Comics Comics “Can Anybody Hear Me?” Tiitu Takalo: Memento Mori Comics

Comics Comics “Can anybody hear me?” Tiitu Takalo: Memento Mori Comics Mari Luoma Romeo and the Monsters First book in a brand new graphic novel series for middle grade readers.. Welcome to the Manor of Monsters! When Romeo Addison turns 12, he will be sent to a private school in a large handsome mansion, as per his great-great-great-granduncle’s last will and testament. The first young man from the Addison family to graduate with honours from the school shall inherit all of the uncle’s sizeable property. But the manor is a strange place, where the teaching staff includes zombies, a ghost and a werewolf. Luckily, Romeo’s clever cousin Jillian also goes to the same school. Together, the cousins begin to unravel the wild secrets of the family estate… Mari Luoma is an illustrator Romeo and the Monsters is a spine-tingling, hair- and comic artist. She mainly raising blend of adventure and comedy. illustrates children’s books Ages: 9+ | Colors: 4/4 | Size: 148 x 210 mm | Pages: 74 | Original and advertising materials language: Finnish | Rights sold: Finnish for her work and designs funny characters for various media. Katie Cook – Elli Puukangas Comics Dark Song A Soul Riders graphic novel Meet the Soul Riders in a standalone adventure gloriously brought to life by the distinguished comics writer Katie Cook and the brilliant upcoming artist Elli Puukangas! 150 pages of epic moments, old legends and wonderful artwork! When the Soul Riders are sent out on a mission to meet with their druid friends, they come to realise all is not well in the area. -

Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, Dc, and the Maturation of American Comic Books

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ScholarWorks @ UVM GROWING UP WITH VERTIGO: BRITISH WRITERS, DC, AND THE MATURATION OF AMERICAN COMIC BOOKS A Thesis Presented by Derek A. Salisbury to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History May, 2013 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, specializing in History. Thesis Examination Committee: ______________________________________ Advisor Abigail McGowan, Ph.D ______________________________________ Melanie Gustafson, Ph.D ______________________________________ Chairperson Elizabeth Fenton, Ph.D ______________________________________ Dean, Graduate College Domenico Grasso, Ph.D March 22, 2013 Abstract At just under thirty years the serious academic study of American comic books is relatively young. Over the course of three decades most historians familiar with the medium have recognized that American comics, since becoming a mass-cultural product in 1939, have matured beyond their humble beginnings as a monthly publication for children. However, historians are not yet in agreement as to when the medium became mature. This thesis proposes that the medium’s maturity was cemented between 1985 and 2000, a much later point in time than existing texts postulate. The project involves the analysis of how an American mass medium, in this case the comic book, matured in the last two decades of the twentieth century. The goal is to show the interconnected relationships and factors that facilitated the maturation of the American sequential art, specifically a focus on a group of British writers working at DC Comics and Vertigo, an alternative imprint under the financial control of DC. -

From Dialogue to Bakhtin's Dialogue

From Dialogue to Bakhtin’s Dialogue: A Critical Review in Learning Disability Research Waseem Mazher, M.A. Teachers College, Columbia University & Jong-Gu Kang, Ed.D. Daegu University Abstract: The purpose of this study was to understand the nature of dialogue used in peer- refereed research articles related to learning disabilities (LD) and instruction. We attempted to evaluate the quality of dialogue in these articles through a lens that Bakhtin and various disability studies scholars offer. In addition, we suggest that disability scholars’ concepts and uses of dialogue provided a way for us to frame our Bakhtinian critique in the broader context of theorizing the social model of disability. From a critical review of these articles, we identified various limitations in ways that dialogue is used to conduct the studies and also in the ways that dialogue is represented by the authors. The studies often minimized the voices of the students labeled as LD. We offer many suggestions for how to present their voices in research and how to improve teaching through conceptualizing learning in a different, more sensitive way as informed by Bakhtin’s notion of dialogue. Key Words: learning disability, dialogue, Bakhtinian Editor’s Note: This article was anonymously peer reviewed. Some authors in the field of special education, including Learning Disabilities (LD), have pointed out the need for researchers to engage in and report dialogue with students labeled as LD (Gallagher, Heshusius, Iano, & Skrtic, 2004; Reid, 1991; Reid & Button, 1995). Although there are several scholars who engage in dialogue with students labeled as LD, these students' voices are still hard to hear.