UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the Metaphor of the Divine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscape Tools

Know your Landscape Tools Long handled Round Point Shovel A very versatile gardening tool, blade is slightly cured for scooping round end has a point for digging. D Handled Round Point Shovel A versatile gardening tool, blade is slightly cured for scooping round end has a point for digging. Short D handle makes this an excellent choice where digging leverage is needed. Good for confined spaces. Square Shovel Used for scraping stubborn material off driveways and other hard surfaces. Good for moving small gravel, sand, and loose topsoil. Not a digging tool. Hard Rake Garden Rake This bow rake is a multi-purpose tool Good for loosening or breaking up compacted soil, spreading mulch or other material evenly and leveling areas before planting. It can also be used to collect hay, grass or other garden debris. Leaf rake Tines can be metal or plastic. It's ideal for fall leaf removal, thatching and removing lawn clippings or other garden debris. Tines have a spring to them, each moves individually. Scoop Shovel Grain Shovel Has a wide aluminum or plastic blade that is attached to a short hardwood handle with "D" top. This shovel has been designed to offer a lighter tool that does not damage the grain. Is a giant dust pan for landscapers. Edging spade Used in digging and removing earth. It is suited for garden trench work and transplanting shrubs. Generally a 28-inch ash handle with D-grip and open-back blade allows the user to dig effectively. Tends to be heavy but great for bed edging. -

Design of Post Hole Digger Machine

International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) ISSN: 2278-0181 Vol. 3 Issue 3, March - 2014 Design of Post Hole Digger Machine Asst. Prof. S. Rajkumar1 , Tibey V Samuel2, K. P. Arunkumar 3, Sanju Paul Kurian 4 1, 2,3,4. Department of Mechanical Jay Shriram Group of Institution Tirupur-638660 Abstract— Conventionally digging a deep holes or larger diameter holes requires more work and rime.so in order to reduce this losses we are planning to design a post hole digger machine for Kamco Tera-trac 4W tractor. Post hole digger machine is used to reduce the man work and time for digging holes. These holes can be used for fixing electric post and different plantation such as rubber plant, coconut, sugar cane etc. For rigid power and support, machine is attached to Kamco Tera-trac 4W tractor by means of PTO (power take off) shaft and three point linkage. PTO shaft of the tractor act as a basic power input and three point linkage provide a rigid support to the machine. Guarded shaft is used to transfer power from PTO shaft to the digger machine. Blades are provided at the end of the machine is used foe digging holes. Various type of holes can be created by using different diameter and length of blades. For designing Post hole digger machine, Creo parametric 1.0 software is used. Creo is 3D mechanical CAD software in which Drafting and assembly can be done easily. Kamco Tera-Trac 4W KOHLER LOMBARDINI Engine Keywords— PTO, tractor, Guarded shaft, blades. KDW 702 Diesel engine, water-cooled, I. -

English Adventures with Cambridge

` Contents Introduction 1 Game Walkthrough: Part I 3 Game Walkthrough: Part II 7 Game Walkthrough: Part III 16 Game Walkthrough: Part IV 24 Notes and practice 26 Answer Keys 27 Worksheet A: Explorer’s Guidebook 29 Worksheet B: The Book of Treasure 30 Worksheet C: The Book of Snow 31 Worksheet D: Explorer’s Guidebook, the end 32 We hope you enjoy English Adventures with Cambridge. Please visit https://www.cambridgeenglish.org/learning-english/games-social/english- adventures/feedback/ to let us know about your experience. Introduction Overview for parents This game was created to help students improve their English and for students to have fun too. These notes were created to help parents (and their children). You and your child do not need to be familiar with Minecraft to play this game. There are four parts (levels) to the game. To support the learning in each part of the game, there are four printable worksheets (A – D) that your child can follow while they’re playing. You can find them at the end of this pack. We recommend that each part is played separately, in this order: • The beginning: Worksheet A • The Book of Treasure: Worksheet B • The Book of Snow: Worksheet C • The end: Worksheet D Each part contains 30 to 40 minutes of play and learning time. Exploring the world In the game, your child will explore the world independently. At the start of the game, a non-player character called Gary tells your child to look around. At this point, you can give your child the Explorer’s Guidebook (Worksheet A). -

Specifications for Small Scale Island Based Contractors

SPECIFICATIONS FOR SMALL SCALE ISLAND BASED CONTRACTORS May 2017 A.1 Preliminaries and General Items Item No. / Name: A.1.1 Consult Communities within the Work Section Category: Labour Intensive Scope: Preliminaries & Unit: Lump Sum (LS) General Items Description: This activity involves consulting the communities in which the contractor will be working and chiefs to discuss work related issues with them and seek agreements to execute the contract successfully. Typical Crew: Typical Hand tools/Equipment: Contractor Hired Vehicle Supervisors Materials: Traditional consultation token for Chiefs in the road custom boundaries Work Specification: 1. Ask for and visit the chief of the custom boundary in which the work section passes through to book appointment to meet all community members and chiefs within the custom boundary 2. Arrange with the CPO to consult communities and conduct awareness education on work related issues focusing on labour recruitment and water sources and write down the names of interested community members willing to work on the road. At all sites, the public will be informed of forthcoming works through public meetings, notices, and installation of signage; 3. Make arrangements for a suitable site to erect a site camp, sources of construction materials, water sources and local skilled labour 4. Discuss, explain and sign Sub-Contract Agreements with the communities and chiefs to recruit interested community members directly or through the chiefs 5. Distribute copies of agreements signed with the communities and chiefs to PWD, the communities and Island Stakeholder Committee 6. Distribute leaflet with construction information, and Contractor contact details including contact phone numbers; 7. -

Land Preparation

U N I T 5 Land Preparation LEARNING / FACILITATING M A T E R I A L S CITRUS PRODUCTION NATIONAL CERTIFICATE I Introduction Welcome to the start of your career in land preparation in citrus production. A career in land preparation for citrus production has never been as popular as it is now; competition is strong and the standards are getting high. So you must aim higher, particularly if you see citrus industry as opportunity to build up your lifelong career. Many career options are also available within the land preparation for citrus production. This unit will look at land preparation, lining and pegging and farmland design. While training, you should make an effort on improving your personal habits, skill and knowledge to get along well with the working industry. All these aspects are essential to achieving success in the world of work. Congratulations for making the decision to study land preparation for citrus production. You have taken the first step towards a very interesting and satisfying career. This learning material covers all the Learning Outcomes for land preparation requirements for the Certificate I programme. LEARNING OUTCOME 1 Table of Contents Demonstrate understanding of land clearing CONTENT PAGE NO In this LO, you will learn to identify tools and equipment, demonstrate the various methods and apply safety measures in land clearing. LO 1Demonstrate understanding of land clearing 3 Before seedlings can be planted, the land must be cleared. Land clearing involves: • Removal of vegetation that may compete with the growth of young trees. a) Identify tools and equipment used for land clearing 3 • Access of machinery. -

EQUIPMENT LIST As of 5/20/2021

Round Rock Tool Lending Center EQUIPMENT LIST As of 5/20/2021 Quantity ITEM DESCRIPTION POWER LANDSCAPE TOOLS 5 GAS POWERED LAWN MOWER 8 GAS WEED TRIMMER 2 WORX ELECTRIC BLOWER 2 GAS BLOWER 6 ELECTRIC HEDGE TRIMMER 8 ELECTRIC POLE TREE SAW 6 1700 PSI PRESSURE WASHER 2 15 INCH SURFACE CLEANER ATTACHMENT 2 JAW SAW 2 ELECTRIC EDGER MANUAL LANDSCAPE TOOLS 12 ROCK RAKE 12 LAWN/LEAF RAKE 4 TRENCHING SHOVEL 8 HEAVY DUTY SQUARE SHOVEL 6 LONG HANDLE SPADE SHOVEL 4 GARDEN SQUARE SHOVEL (2 L & 2 S) 2 PICKAXE 8 MANUAL POLE TREE SAW 4 HEDGE SHEAR 6 SMALL PRUNING SHEAR 8 LONG HANDLED LOPPER 6 GARDEN HANDCLAW TOOL 1 SEED SPEADER (WALK-BEHIND) 2 2 GALLON SPRAYER 8 SCOOP SHOVEL 4 HULA HOE 6 UPRIGHT BROOM 4 PUSH BROOM 5 DUST PAN 6 WHEELBARROW 4 BOW SAW 1 MANUAL POSTHOLE DIGGER 1 POST DRIVER 1 MEASURING WHEEL 4 TOW STRAPS 1 2 SLEDGE HAMMER 10 100’ EXTENSION CORD 1 TAMPER 2 STEP LADDER 2 MANUAL GARDEN TILLER 1 3 TINE MANUAL CULTIVATOR 1 BORDER EDGER 4 WEEDER 4 PRYBARS (LONG & SHORT) 2 STEEL BRUSHES 1 FLOOR SCRAPER 4 DEAD BLOW/RUBBER MALLOT 1 13’ EXTENSION LADDER 10 CAULKING GUNS (28oz and 10oz) 5 5 GAL BUCKETS 1 20 GAL (GREY) TRASH CAN 3 32 GAL (GREY) TRASH CAN 2 3 YARD DUMPSTER BAGS TOOL BOX- HAMMERS, 3 SCREWDRIVERS, SOCKET SETS, SCREWS, NAILS, PLIERS, VICE GRIPS, WRENCHES, PIPE CUTTERS 1 SHOP VAC SUPPLIES & SAFETY EQUIP. 3 5 GAL GAS CAN 2 1 GAL GAS CAN (TRIMMER MIX) 1 WEED TRIMMER STRING 1 HEARING PROTECTION HEADSET 2 FIRST AID KIT 1 FIRE EXTINGUISHER 1 IGLOO WATER COOLER & HOLDER 1 HUSKY RECHAREABLE FLASHLIGHT 4 HEADLAMP 4 LED FLASHLIGHT 1 BUNGEE CORD SET 1 100‘ WATER HOSE W/SPRAY NOZZLE 10 TRAFFIC CONE 12 HARD HAT 12 SAFETY GOGGLES 19 SAFETY VEST 4 boxes WORK GLOVES 2 boxes EAR PLUGS-FOAM 100/BOX 2 boxes DUST MASK-CLOTH 50 COUNT 4 boxes LAWN & GARDEN TRASH BAGS 2 FOLDING TABLE 2 6 FOLDING CHAIR 1 10’ X 10’ TENT SHADE 1 STANLEY NAIL/SCREW ORGANIZER 40 TRASH GRABBER SAFETY MANUALS For more information please call the Neighborhood Services Coordinator at (512) 671-2778. -

Essential Garden Tools and Maintainence

ESSENTIAL GARDEN TOOLS ANDS THEIR MAINTAINENCE The key to easier and more successful garden work is having at hand and taking care of the correct tools. Below is a list of essential tools to meet most of your gardening needs, however, before begging, borrowing or buying tools you should find a proper storage space for them for maintenance and security purposes. TOOL PURPOSE OR USAGE Heavy wooden frame with wire screen for shifting debris Riddle from soil. Planting shovel For light work, small plantings. Crowbar Removing rocks and embedded debris. File Sharpening tools. Turning compost heap, digging holes, digging up plants or Spading fork or spade debris. Cultivator Loosening soil, removing weeds. Broom or fan rake Raking leaves or rubbish. Shears Pruning, clipping, trimming. Tamper Smoothing newly dug garden beds. Trowel, hand fork, cultivator-small holes, planting bulbs, Garden hand tools weeding loosening soil. Hose and spray nozzle hydrant adapter To attach hose to hydrant. Clippers Trimming and cutting. Wheelbarrow, hand truck and old kitchen knife Good for digging up the random weed. Watering and dabble For planting seeds and seedlings. Edger For trimming lawns, paths. Metal rake Smoothing soil after planting, removing debris. Hoes For turning soil, deep cultivation. Common hand tools Hammer, nails, screwdrivers, pliers, wire cutters. For cutting tall grasses, weed. Note* right hand scythe Steaks, ties, grass whip or scythe must be used only for night handers; lefties must purchase left handed scythe, grass whip or sickle Dolly Cart debris out, transport trees. Heavy duty shovel sticks and twine or planting For laying out rows. line Buckets and baskets For water, compost, tools and weeds. -

Lot # Name Description Seller Code 1 Bosch Dishwasher White

Lot # Name Description Seller Code 1 Bosch Dishwasher White Bosch Dishwasher 100 2 Magic Chef Microwave New in Box Magic Chef Microwave 900 Watt, Silver 100 3 Sharp Convection Microwave White Sharp Convection Microwave 100 4 Bosch Axxis Dryer White Axxis Bosch Electric Dryer 100 5 Bosch Axxis Washing Machine White Bosch Axxis Washing Machine 100 6 Roper Wall Oven Gas White Roper Wall Oven 100 1 Mr Coffee 10 Cup Coffee Maker, 1 Procter Silex 12 Cup Coffee Maker, 3 Coffee Mugs, Small Wooden Cutting Board, 2 Wire 7 2 Coffee Makers, 2 Wire Shelves, 1 Panasonic Toaster Oven Shelving Units, 1 with Contents, 1 Panasonic Toaster Oven 100 1 Metal Lamp, 1 Wooden Table with Built in Lamp, 1 Tall Floor 8 1 Metal Lamp, End Table with Built in Lamp, 1 Tall Floor Lamp Lamp 100 9 Eureka Vacuum Cleaner Red Eureka Vacuum Cleaner 100 Small Memorex CD/Radio, 1 Pair of Jvc Stereo Speakers, 1 Pair Small Memorex CD/Radio, 1 Pair of Jvc Stereo Speakers, 1 Pair of 10 of Sharp Stereo Speakers Sharp Stereo Speakers 100 11 1 Used Off White Toilet 1 Used Off White Toilet 100 12 White Double Sink with Faucet Possible Cast Iron White Double Sink with Faucet 100 13 White Bathroom Vanity Sink with Faucet White Bathroom Vanity Sink with Faucet 100 2 Stainless Steel Chafer Serving Trays with Lids and Handles, 4 2 Stainless Steel Chafer Serving Trays with Lids and Handles, 4 Full 14 Full Sterno Cans Sterno Cans 100 1 Single Stainless Steel Kitchen Sink with Faucet, Sprayer and 1 Single Stainless Steel Kitchen Sink with Faucet, Sprayer and Dish 15 Dish Dispenser Dispenser -

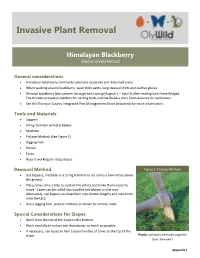

Invasive Plant Removal

Invasive Plant Removal Himalayan Blackberry (Rubus aremeniacus) General considerations Himalayan blackberry commonly colonizes roadsides and disturbed areas. When working around blackberry, wear thick pants, long sleeved shirts and leather gloves. Remove blackberry late summer through early spring (August 1 – April 1) after nesting birds have fledged. The thickets provide protection for nesting birds and the flowers are a food resource for pollinators. See the Thurston County Integrated Pest Management Sheet (attached) for more information. Tools and Materials Loppers String Trimmer w/metal blades Machete Pickaxe-Mattock (See Figure 1) Digging Fork Shovel Tarps Rope if working on steep slopes Removal Method Figure 1: Pickaxe-Mattock Use loppers, machete or a string trimmer to cut canes a few inches above the ground. Place canes onto a tarp to contain the plants and make them easier to move. Canes can be rolled into bundles and placed on the tarp. Alternately, use loppers to chop them into shorter lengths and rake them onto the tarp. Use a digging fork, pickaxe-mattock or shovel to remove roots. Special Considerations for Slopes Work from the top of the slope to the bottom. Work carefully to reduce soil disturbance as much as possible. If necessary, use ropes to haul tarped bundles of canes to the top of the slope. Photo: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ User: Stemonitis Appendix 1 Invasive Plant Removal—Himalayan Blackberry Disposal Blackberry must be disposed of in the landfill if taken off-site. Small amounts can be placed in the garbage. To compost on site, pile on tarps to keep them from rooting into the ground. -

Agricultural Guide to Controlling Windblown Sand and Dust

Agricultural Guide to Controlling Windblown Sand and Dust Information in this Guide applies to high elevation desert regions of Southern California. It is based on approximately 20 years of research conducted by the Dustbusters Research Group in the Antelope Valley of Northern Los Angeles County. Table of Contents Summary . 3 Overview of the Problem . 4 History . 4 Why Dust Blows . 5 Effective Dust Control Measures . 6 Cost-Sharing Programs and Conservation Technical Assistance . 6 Specific Practices . 8 Cover Crops in Field Cropping Systems . 8 Stripcropping . 10 Agronomic Practices for Planting Cover Crops . 10 Cover Crops in Perennial Tree and Vine Systems . 11 Long Term Native Plant Cover . 11 Exposed Desert . 11 Wind Breaks . 11 Solid Fences . 12 Porous Fences . 12 Straw Bales . 12 Soil Surface Modification . 12 Berms . 13 Large Trees and Shrubs . 13 Surface Coverings . 14 Acknowledgments . 15 Resources Guide . 16 Appendix: Irrigation Requirements . 18 Dustbusters Research Group . Back Cover Front Cover: Blowing dust in the Antelope Valley has led to reduced visibility and serious traffic accidents. A number of techniques suppress blowing dust, even in very sandy areas. Back Cover: California poppies, which are native vegetation, stabilize the soil. Dustbusters Research Group Agricultural Guide to Controlling Windblown Sand and Dust Page 2 – June 2011 Summary Growers in the high elevation Mojave Desert and other Southwestern U .S . locations encounter extended droughts, high winds, soil erosion, and other circumstances that result in blowing dust. Agricultural soils may be exposed briefly between crops, or as fields are fallowed for 1 to 3 years, grazed by sheep, or taken completely out of production . -

Farm Tools- Supplies

S/N Item Description UOM Quantity Unit price Total 1 Hoe piece Hoe handle Garden Hoe with 59 1/2 in Wood Handle, Origin 2 Mexico. piece Mattock with Handle(A mottock with a digger point an 3 wider cutter blade, made in china) piece 4 Pick axe (with handle) (Jidib) (Pickaxe with edge point, Local) piece 5 Axe piece 6 Axe handle piece 7 Kawawa piece 8 Shovel piece Spade with handle (Round mouth shovel with socket fitting to 9 hand, made up of all metal from China) piece 10 Garden trowel piece 11 Garden rake with 14 teeth, all made up of metal, made in china. piece 12 Metal watring can, 10L Local 13 Watering can, 10L Garden watering can made in china piece 14 diesel water pump piece 15 submissible water pump piece 16 Plastic water pipe (6m) piece 17 Metal water pipe (6m) piece 18 Drip irrigation irrigtion pipe (100m) roll 19 Welding machine piece 20 Sickle steel with long handle made in china piece 21 Saw piece 22 Plane piece 23 Builders Trowel piece Wheel Barrow (Wheelbarrow with a cpaicity of carrying trayer m(75- 90 litres), Total load must be 150 kg minimuim. The tyre 24 should be foam filled tires.made in Saudi Arabia) piece 25 Wire strainer piece 26 Total station (survey equipment) piece 27 Grinder unit Heavy Duty hand gloves 28 Grafting Knife unit 29 Heavy Duty hand gloves, Right gloves, size 1011 Pair Tape measure 5 meter 30 Tape measure 30 meter long YUHANG made in China piece 31 Tape measure 50 meter long YUHANG made in China piece 32 Tape measure 100 meter long YUHANG made in China piece Traditional Axe (Gudin) with Handle (Maca -

Sr-86-32 Equipment for Making Access Holes Through Arctic Sea

Special Report 86-32 US Army Corps November 1986 of Engineers Cold Regions Research & Engineering Laboratory Equipment for making access holes through arctic sea ice Malcolm Mellor Prepared for NAVAL CIVIL ENGINEERING LABORATORY Approved for public release; distribution Is unlimited. Unclassified SEC URITY CLASSIF ICATIO N OF THIS PAGE Form Approve d REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OM B No 0704·0 1BB ElIp Date Ju n ]O, 1986 , . REPORT SECUR ITY CLASSI FICATION 1b RESTR ICTIV E MARKINGS Unclassified 2 • . SEC URIT Y ClASSIFI(A nON A UTH ORITY 3 DISTR IBUTION I AVAILAB ILITY OF REPORT 2b. DECLASSIF ICATION / DOWNGRADING SCHED ULE Approved for public release; d istribution is unlimited. 4. PERFORMING ORGANIZATI ON REPOR T NUMBER(S ) S M ONITORING ORGAN IZA TI ON RE PORT NUMBER(S) Specia l Re po rt 86-32 6 • . NAM E OF PERFO RMING O RGAN IZATION 6b. OFFIC E SY MBOL 7. NAME OF MONITORING O RGANIZATION U.S. Army Cold Regions Researc h (If applicable) Naval Civil Enginee ring Laboratory and Engineering Laboratory C RREL 6c. ADDRESS (City, State, and ZIP Code) 7b ADDRESS (C;ty, State, and ZIP Code) 72 Lyme Road Port Hueneme, Califo rnia 93043-5003 Hanove r, New Hampsh ire 03755- 1290 8• . NAME OF FUNDING / SPONSORI NG 8b. OFFIC E SY MBOL 9. PROCUREMENT INSTR UMENT IDE NTIFICA TION NUMBER ORGANIZATION (I f appl;cable) N68305 86WR60128 8e. ADDRES S (City, State, and ZIP Code) 10. SOURCE O F FUNDING NUMBERS PROGRAM PROJ ECT TASK WO RK UNIT ELEMENT NO. NO NO ACCESS IO N NO 11 .