What Motivates Composers to Compose?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Eighteenth-Century Music in a Twenty-First Century Conservatory of Music Or Using Haydn to Make the Familiar Exciting by Mary

1 Morrow, Mary Sue. “Eighteenth-Century Music in a Twenty-First Century Conservatory of Music, or Using Haydn to Make the Familiar Exciting.” HAYDN: Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America 6.1 (Spring 2016), http://haydnjournal.org. © RIT Press and Haydn Society of North America, 2016. Duplication without the express permission of the author, RIT Press, and/or the Haydn Society of North America is prohibited. Eighteenth-Century Music in a Twenty-First Century Conservatory of Music or Using Haydn to Make the Familiar Exciting by Mary Sue Morrow University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music I. Introduction Teaching the history of eighteenth-century music in a conservatory can be challenging. Aside from the handful of music history and music theory students, your classes are populated mostly by performers, conductors, and composers who do not always find the study of music history interesting or even necessary. Moreover, when you step in front of a graduate-level class at the College-Conservatory of Music at the University of Cincinnati, everybody in the class is going to know all about the music of the eighteenth century: they’ve played Bach fugues and sung in Handel choruses; they’ve sung Mozart arias and played Haydn string quartets or early Beethoven sonatas. They have also been taught to revere these names as the century’s musical geniuses, but quite a number of them will admit that they are not very interested in eighteenth-century music, particularly the music from the late eighteenth-century: It is too ordinary and unexciting; it all sounds alike; it is mostly useful for teaching purposes (definitely the fate of Haydn’s keyboard sonatas and, to a degree, his string quartets). -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Program Notes When Mozart Wrote the Three Divertimentos, KV 136-8 at the Age of 16, He Had Already Spent More Than Two Years Away from His Hometown of Salzburg

Program Notes When Mozart wrote the three Divertimentos, KV 136-8 at the age of 16, he had already spent more than two years away from his hometown of Salzburg. He had lived in London and Paris and travelled throughout Austria, Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Italy. Besides giving concerts at court, he met many famous musicians of the time and had opportunities to hear and study their music. Mozart’s early compositions are therefore often case studies in the styles and traditions of where his travels had most recently taken him. The Divertimentos were written in the winter 1771/2, after the second of three extended trips to Italy. A third journey was already in the planning and the Italian influence on Mozart’s writing is evident. It is uncer- tain whether the pieces are meant for a specific occasion; the title ‘Divertimento’ was in fact even added by another hand, possibly that of his father Leopold. The three-movement structure follows the pattern of the early Italian Sinfonia type, but J. Haydn and J.C. Bach have strongly influenced his compositions as well. Young Mozart met the two composers in London and looked up to them mentors and friends. The scholar Alfred Einstein hypothesizes that Mozart wrote the three pieces anticipating the need for some new symphonies during his next Italian journey. If required on short notice, Mozart would simply have added winds at the last moment. Before the birth of his gifted children, Leopold Mozart had made a business of writing musical novelties. He was a violinist, conductor, and teacher, his book ‘Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule’ is alongside the textbooks by Quantz and C. -

SONGS DANCES Acknowledgments & Recorded at St

SONGS DANCES Acknowledgments & Recorded at St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, Jacksonville, Florida on June 13 and 14, 2018 Jeff Alford, Recording Engineer Gary Hedden, Mastering Engineer in THE SAN MARCO CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY collaboration THE LAWSON ENSEMBLE with WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1753 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2018 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. SanMarco_1753_book.indd 1-2 10/18/18 9:36 AM The Music a flute descant – commences. Five further variations ensue, each alternating characters and moods: a brisk second variation; a slow, sad, waltzing third; a short, enigmatic fourth; a sprawling fifth, this the Morning Elation for oboe and viola by Piotr Szewczyk (2010) emotional heart of the composition; and a contrapuntal sixth, which ends with a restatement of the theme Piotr Szewczyk was fairly new to Jacksonville when I asked him if he could compose an oboe/viola duo for now involving the flute. us in 2010, so I did not expect the enthusiasm and speed in which he composed “Morning Elation”! Two In all, it’s a complex, ambitious score, a glowing example of the American Romantic style of which days later he greeted me with the news that he had a burst of inspiration and composed our piece the day Beach, along with George Whitefield Chadwick, John Knowles Paine, and Arthur Foote, was such a wonder- before. -

IMAGO MUSICAE Edenda Curavit Björn R

International•Yearbook•of•Musical•Iconography Internationales•Jahrbuch•für•Musikikonographie Annuaire•International•d’Iconographie•Musicale XXIX Annuario•Internazionale•di•Iconografia•Musicale Anuario•Internacional•de•Iconografía•Musical Founded by the International Repertory of Musical Iconography (RIdIM) IMAGO MUSICAE Edenda curavit Björn R. Tammen cum Antonio Baldassarre, Cristina Bordas, Gabriela Currie, Nicoletta Guidobaldi atque Philippe Vendrix Founding editor 1984–2013 Tilman Seebass IMAGO MUSICAE XXIX INSTITUT FÜR KUNST- UND MUSIKHISTORISCHE FORSCHUNGEN Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften Wien CENTRE D’ÉTUDES SUPÉRIEURES DE LA RENAISSANCE ISSN • 0255-8831 Université François-Rabelais de Tours € 80.00 ISBN • 978-7096-897-2 LIM Libreria•Musicale•Italiana Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, UMR 7323 IMAGO MUSICAE International•Yearbook•of•Musical•Iconography Internationales•Jahrbuch•für•Musikikonographie Annuaire•International•d’Iconographie•Musicale Annuario•Internazionale•di•Iconografia•Musicale Anuario•Internacional•de•Iconografía•Musical Edenda curavit Björn R. Tammen cum Antonio Baldassarre, Cristina Bordas, Gabriela Currie, Nicoletta Guidobaldi atque Philippe Vendrix Founding editor 1984–2013 Tilman Seebass IMAGO MUSICAE XXIX Libreria•Musicale•Italiana Founded by the International Repertory of Musical Iconography (RIdIM) Graphic design and Layout: Vincent Besson, CNRS-CESR ISSN: 0255-8831 ISBN: 978-88-7096-897-2 © 2017, LIM Editrice, Lucca Via di Arsina 296/f – 55100 Lucca All rights reserved – Printed in -

Mozart's Scatological Disorder

loss in this study, previous work has been descriptive Our study shows that there is a potential for hearing in nature, presenting the numbers of cases of hearing damage in classical musicians and that some form of loss, presumed to have been noise induced orcomparing protection from excessive sound may occasionally be hearing levels with reference populations.'7-8 Both needed. these descriptive methods have shortcomings: the former depends on the definition of noise induced 1 Health and safety at work act 1974. London: HMSO, 1974. 2 Noise at work regulations 1989. London: HMSO, 1989. hearing loss, and the latter depends on identifying a 3 Sataloff RT. Hearing loss in musicians. AmJ Otol 1991;12:122-7. well matched reference population. Neither method of 4 Axelsson A, Lindgren F. Hearing in classical musicians. Acta Otolaryngol 1981; 377(suppl):3-74. presentation is amenable to the necessary statistical 5Burns W, Robinson DW. Audiometry in industry. J7 Soc Occup Med 1973;23: testing. We believe that our method is suitable for 86-91. estimating the risk ofhearing loss in classical musicians 6 Santucci M. Musicians can protect their hearing. Medical Problems ofPerforming Artists 1990;5:136-8. as it does not depend on identifying cases but uses 7 Rabinowitz J, Hausler R, Bristow G, Rey P. Study of the effects of very loud internal comparisons. Unfortunately, the numbers music on musicians in the Orchestra de la Suisse Romande. Medecine et Hygiene 1982;40:1-9. available limited the statistical power, but other 8 Royster JD. Sound exposures and hearing thresholds of symphony orchestra orchestras might be recruited to an extended study. -

Salzburg, Le 24 D'avril3 Ma Trés Chére Cousine!4 1780 You Answered My

0531.1 MOZART TO MARIA ANNA THEKLA MOZART,2 AUGSBURG Salzburg, le 24 d’avril3 Ma trés chére Cousine!4 1780 You answered my last letter5 so nicely that I do not know where to look for words with which to manifest adequately my statement of gratitude, [5] and at the same time to assure you anew of the extent to which I am, madam, Your most obedient servant and most sincere cousin [BD: ALMOST THE WHOLE PAGE IS LEFT BLANK UNTIL THE SIGNATURE COMES:] Wolfgang Amadé Mozart I would have liked to write more, but the space, as you see, [10] is too Adieu, adieu restricted. But now, in joking and earnest, you must surely forgive me this once for not answering your most treasured letter as it deserves, from one word to the next, [15] and allow me to write only what is most necessary; in the coming days I will try to improve my mistakes as much as possible – it is now 14 days since I replied6 to Msr. Böhm7 – my only concern is to know that my letter did not go astray, which I would greatly regret – for otherwise I know only too well that Msr. Böhm is only too busy every day [20] – be it as it may he be, I would be so glib, my dearest squib, as to ask you to convey a thousand compliments – and I wait only for his say-so, and the finished aria8 will be there. – I heard that Munschhauser9 is ill as well; is that true? – that would not be good for Msr. -

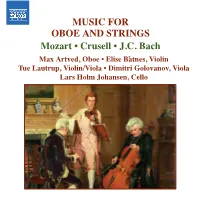

MUSIC for OBOE and STRINGS Mozart • Crusell • J.C. Bach

557361bk USA 26/8/04 7:30 pm Page 4 Max Artved The oboist Max Artved was born in 1965 and joined the Tivoli Boys’ Guard at the age of twelve. In 1980 he entered the Royal Danish Academy of Music, studying with Jørgen Hammergaard, and subsequently with Maurice Bourgue in Paris and Gordon Hunt in London. He made his solo MUSIC FOR début in 1990 and joined the Royal Danish Orchestra in 1991, later the same year becoming principal oboe with the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra. Awards include the Jacob Gade Scholarship, the Gladsaxe Music Prize and the Music Critics’ Artist Prize. His career has brought solo OBOE AND STRINGS engagements in Scandinavia and throughout Europe, and he has contributed to recordings released by dacapo and by Naxos Mozart • Crusell • J.C. Bach Elise Båtnes The violinist Elise Båtnes was appointed leader of the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra in 2002. She has appeared as a soloist, particularly throughout Scandinavia, and was leader of the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra. She has been a Max Artved, Oboe • Elise Båtnes, Violin member of the Vertavo Quartet, and has served as artistic director of the Bergen Chamber Ensemble. Tue Lautrup, Violin/Viola • Dimitri Golovanov, Viola Dimitri Golovanov Dimitri Golovanov is a native of St Petersburg, where he studied at the Conservatory, before emigrating from the Soviet Union. He has served as principal violist in the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra since 1994. Lars Holm Johansen, Cello Lars Holm Johansen Lars Holm Johansen was principal cellist in the Royal Danish Orchestra until August 2002, and is well known for his collaboration in chamber music and as a co-founder of the Copenhagen Trio. -

Download Booklet

Classics Contemporaries of Mozart Collection COMPACT DISC ONE Franz Krommer (1759–1831) Symphony in D major, Op. 40* 28:03 1 I Adagio – Allegro vivace 9:27 2 II Adagio 7:23 3 III Allegretto 4:46 4 IV Allegro 6:22 Symphony in C minor, Op. 102* 29:26 5 I Largo – Allegro vivace 5:28 6 II Adagio 7:10 7 III Allegretto 7:03 8 IV Allegro 6:32 TT 57:38 COMPACT DISC TWO Carl Philipp Stamitz (1745–1801) Symphony in F major, Op. 24 No. 3 (F 5) 14:47 1 I Grave – Allegro assai 6:16 2 II Andante moderato – 4:05 3 III Allegretto/Allegro assai 4:23 Matthias Bamert 3 Symphony in G major, Op. 68 (B 156) 24:19 Symphony in C major, Op. 13/16 No. 5 (C 5) 16:33 5 I Allegro vivace assai 7:02 4 I Grave – Allegro assai 5:49 6 II Adagio 7:24 5 II Andante grazioso 6:07 7 III Menuetto e Trio 3:43 6 III Allegro 4:31 8 IV Rondo. Allegro 6:03 Symphony in G major, Op. 13/16 No. 4 (G 5) 13:35 Symphony in D minor (B 147) 22:45 7 I Presto 4:16 9 I Maestoso – Allegro con spirito quasi presto 8:21 8 II Andantino 5:15 10 II Adagio 4:40 9 III Prestissimo 3:58 11 III Menuetto e Trio. Allegretto 5:21 12 IV Rondo. Allegro 4:18 Symphony in D major ‘La Chasse’ (D 10) 16:19 TT 70:27 10 I Grave – Allegro 4:05 11 II Andante 6:04 12 III Allegro moderato – Presto 6:04 COMPACT DISC FOUR TT 61:35 Leopold Kozeluch (1747 –1818) 18:08 COMPACT DISC THREE Symphony in D major 1 I Adagio – Allegro 5:13 Ignace Joseph Pleyel (1757 – 1831) 2 II Poco adagio 5:07 3 III Menuetto e Trio. -

Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart's View of the World

Between Aufklärung and Sturm und Drang: Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart’s View of the World by Thomas McPharlin Ford B. Arts (Hons.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy European Studies – School of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Adelaide July 2010 i Between Aufklärung and Sturm und Drang: Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart’s View of the World. Preface vii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Leopold Mozart, 1719–1756: The Making of an Enlightened Father 10 1.1: Leopold’s education. 11 1.2: Leopold’s model of education. 17 1.3: Leopold, Gellert, Gottsched and Günther. 24 1.4: Leopold and his Versuch. 32 Chapter 2: The Mozarts’ Taste: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s aesthetic perception of their world. 39 2.1: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s general aesthetic outlook. 40 2.2: Leopold and the aesthetics in his Versuch. 49 2.3: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s musical aesthetics. 53 2.4: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s opera aesthetics. 56 Chapter 3: Leopold and Wolfgang, 1756–1778: The education of a Wunderkind. 64 3.1: The Grand Tour. 65 3.2: Tour of Vienna. 82 3.3: Tour of Italy. 89 3.4: Leopold and Wolfgang on Wieland. 96 Chapter 4: Leopold and Wolfgang, 1778–1781: Sturm und Drang and the demise of the Mozarts’ relationship. 106 4.1: Wolfgang’s Paris journey without Leopold. 110 4.2: Maria Anna Mozart’s death. 122 4.3: Wolfgang’s relations with the Weber family. 129 4.4: Wolfgang’s break with Salzburg patronage. -

DMG · Leopold!

LEOPOLD! 300 Jahre Leopold Mozart · Jubiläumsmagazin der Deutschen Mozart-Gesellschaft HEIMAT AUGSBURG DER NETZWERKER SEINE MUSIK DIE VIOLINSCHULE LEOPOLD DURCH DIE BRILLE DER NACHWELT MIT KONZERT-TIPPS: JubiLeo! Deutsches Mozartfest 11. — 26. Mai 2019 EDITORIAL Liebe Mitglieder der DMG, liebe Augsburgerinnen und Augsburger, Anlässlich des 300. Geburtstags von Leopold Mozart Vieles in den Geschichten rund um Leopold führt hat es sich die Deutsche Mozart-Gesellschaft mit die- uns auch immer wieder zurück zu seinen Augsburger sem Jubiläumsmagazin zur Aufgabe gemacht, die viel- Wurzeln – dahin, wo er die geistigen Grundlagen sei- seitige Persönlichkeit des Augsburger Bürgersohnes nes späteren Wirkens erhalten haben muss. Angesichts neu zu beleuchten. Wie bei einem Kaleidoskop fokus- der Bedeutung, die nicht nur musikgeschichtlich, son- sieren die Autoren dabei aus einem jeweils anderen dern auch kulturgeschichtlich dem Augsburger Leopold Blickwinkel heraus den Menschen, Musiker, Erzieher, Mozart beizumessen ist, kommt seiner Würdigung mehr Komponisten, Reisenden und Schrift steller und es ent- als nur eine lokale Dimension zu. Das JubiLeo! bietet die steht das facetten reiche Bild eines Mannes, ohne des- Möglichkeit, seine in der Memoria der Stadt fest ver- sen Wirken die Musikgeschichte ein Stück weit anders ankerte Persönlichkeit nicht nur mit diesem Magazin, verlaufen wäre. sondern auch mit einer Reihe von hochkarätigen Ver- anstaltungen – vom Deutschen Mozartfest bis hin zum Bislang ist Leopold Mozart eher nur im Kontext der Internationalen Violinwettbewerb – in das Rampenlicht Wunderkindgeschichte um Wolfgang Amadé wahr- einer breiteren Öffentlichkeit zu stellen und einer Neu- genommen worden. Folgt man aber seinen Lebens- bewertung zu unterziehen. stationen, entsteht doch das Bild eines selbstbewussten Selfmademan und Allrounders, der selbst über eine Eine erhellende Lektüre wünscht Ihnen Ihr hohe Begabung in allen Wissensgebieten seiner Zeit verfügt haben muss. -

Mozart, Bäsle-Briefe

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 1756 - 1791 D i e B ä s l e - B r i e f e Mozarts Bäsle, Maria Anna Thekla Mozart, wurde 1759 als Tochter von Leopold Mozarts Bru- der Franz Aloys in Augsburg geboren. Die intime Freundschaft zwischen dem Vetter und der drei Jahre jüngeren Cousine begann mit dem Aufenthalt in Augsburg vom 11. bis 26. Oktober 1777. Im September war Mozart zusammen mit seiner Mutter aus Salzburg aufgebrochen, um zu versuchen, an einem Fürstenhof eine Anstellung zu finden. In München waren sie bereits erfolglos, als sie in Augsburg Station machten. Auch im weiteren Verlauf der Reise, die über Mannheim bis nach Paris führte, erfüllten sich die Hoffnungen nicht. Mozarts Mutter starb 1781 in Paris an Typhus und er mußte nach Salzburg zurückkehren. In den Bäsle-Briefen scheint von all diesen Schwierigkeiten und Kümmernissen nichts auf. Im letzten Brief Mozarts an die Cousine ist allerdings in dem völlig veränderten Ton die Entfremdung der beiden zu spüren. 1784 brachte Maria Anna Thekla eine un- eheliche Tochter zur Welt, wahrscheinlich von einem Augsburger Chorherrn. 1814 zog sie nach Bayreuth zu ihrer Tochter, wo sie 1841 starb. Ihre Briefe an Mozart sind nicht erhalten. Mozarts prüde Biographen und Herausgeber hatten lange Probleme mit der drastischen und derben Sprache der Briefe. Noch 1914 in der ersten kritischen Gesamtausgabe der Briefe wurden alle anstößigen Stellen eliminiert. ____________________________________________________________________________ 1. Brief [Mannheim, den 31. 10. 1777] Das ist curiös! ich soll etwas gescheutes schreiben und mir fällt nichts gescheides ein. Vergessen Sie nicht den Herrn Dechant zu ermahnen, damit er mir die Musicalien bald schickt.