Angelman Syndrome Clinical Management Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Report

RARERARE PEDIATRICPEDIATRIC DISEASESDISEASES SPECIAL REPORT SELECTED ARTICLES Rare Diseases Pose a Pressing Challenge: Are State-by-State Differences in Newborn 02 09 Get the Diagnostic Work Done Swiftly Screening an Impediment or Asset? Rare Epileptic Encephalopathies: Neurodevelopmental Concerns May Emerge 05 21 Update on Directions in Treatment Later in Zika-exposed Infants EDITOR’S NOTE housands of rare diseases have been identified, but only T 35 core conditions are on the federal Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP). But the majority of states don’t screen for all 35 conditions. Read on to learn about the pros and cons of state-by- state differences in newborn screening for rare disorders. But newborn Catherine Cooper screening is not the only way to learn about a child’s rare disease. There Nellist is genetic screening, and now it is more widely available than ever. But how to make sense of that information? Certified genetic counselors will help, but health care providers need education about what to do when a rare disease is diagnosed. In this Rare Pediatric Diseases Special Report, there are resources for you as health care providers and for your patients provided by the National Institutes of Health and by the National Organization for Rare Disorders. Explore a synopsis of existing and emerging treatments of three rare epileptic encephalopathies that occur in infancy and early childhood— West syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and Dravet syndrome. Learn about important advancements in the treatment of three rare pediatric neuromuscular disorders—spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), and X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM)—and how improved quality of life and survival will challenge current EDITOR systems of transition care. -

Looks Like Angelman Syndrome but Isn’T – What Is in the Differential?

R.C.P.U. NEWSLETTER Editor: Heather J. Stalker, M.Sc. Director: Roberto T. Zori, M.D. R.C. Philips Research and Education Unit Vol. XXII No. 1 A statewide commitment to the problems of mental retardation January 2011 R.C. Philips Unit ♦ Division of Pediatric Genetics, Box 100296 ♦ Gainesville, FL 32610 ♦ (352)294-5050 E Mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Website: http://www.peds.ufl.edu/divisions/genetics/newsletters.htm Looks like Angelman syndrome but isn’t – What is in the differential? Charles A. Williams, MD Division of Pediatric Genetics & Metabolism University of Florida Angelman syndrome Differential Diagnosis of Angelman syndrome (AS) Angelman syndrome is a neurobehavioral disorder characterized by Individuals with AS-like features often present with psychomotor delay and/or developmental delay, progressive microcephaly, ataxic gait, absence of seizures and the differential diagnosis can be broad, encompassing such speech, seizures and a characteristic behavioral phenotype which includes non-specific entities as cerebral palsy, static encephalopathy, autism and happy demeanor and spontaneous bouts of laughter. AS was originally mitochondrial encephalomyopathy. Tremulousness and jerky limb called the “Happy Puppet Syndrome” in its description by Harry Angelman in movements, seen in most individuals with AS may help distinguish it from 1965 in an attempt to describe the upheld hands, clumsy gait and happy these conditions (see table below for other helpful distinguishing features). demeanor of individuals with this condition. The incidence is estimated to be Specific syndromes that mimic AS are reviewed below. Table 1 provides a between 1 in 15,000 and 1 in 20,000 live births. -

HIGH RISK 1P36 This Pregnancy Is Classified As HIGH RISK by This Screen for a Deletion at 1P36, Which Is Associated with 1P36 Deletion Syndrome

Patient Report |FINAL Client: Example Client ABC123 Patient: Patient, Example 123 Test Drive Salt Lake City, UT 84108 DOB 4/3/1982 UNITED STATES Gender: Female Patient Identifiers: 01234567890ABCD, 012345 Physician: Doctor, Example Visit Number (FIN): 01234567890ABCD Collection Date: 01/01/2017 12:34 Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing for Fetal Aneuploidy with Microdeletions ARUP test code 2010232 Result Summary HIGH RISK 1p36 This pregnancy is classified as HIGH RISK by this screen for a deletion at 1p36, which is associated with 1p36 deletion syndrome. This result should be confirmed by a diagnostic test. Dependent on fetal fraction, 7 to 17% of pregnancies classified as HIGH RISK are found to have 1p36 deletion syndrome. TEST INFORMATION: Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing for Fetal Aneuploidy (Powered by Constellation) with or without Microdeletions METHODOLOGY: DNA isolated from the maternal blood, which contains placental DNA, is amplified at 13,300+ loci using a targeted PCR assay and sequenced using a high-throughput sequencer. Sequence data are analyzed using Natera's Constellation software to estimate the fetal copy number and identify whole chromosome abnormalities for chromosomes 13, 18, 21, X, and Y as well as fetal sex. Barring QC failures and fetal fractions below the performance limits of the algorithm, the minimum confidence threshold is 0.98 for a high risk call. For both low risk and high risk calls, the majority of specimens will have a confidence of >0.99 across all regions tested. If a sample fails to meet the quality threshold, no result will be reported for one or more chromosomes. Microdeletions: An additional 6,600+ loci are amplified to estimate the fetal copy numbers of chromosomal regions attributed to 22q11.2, Prader-Willi, Angelman, Cri-du-chat, and 1p36 deletion syndromes. -

Autism in Genetic Syndromes: Implications for Assessment and Intervention

© © Cerebra Cerebra 2012 2009 Autism in genetic syndromes: Implications for assessment and intervention. Introduction Dr. Jo Moss and Prof. Chris Oliver This briefing has been prepared to help parents and carers of children with genetic syndromes understand how and why autism spectrum disorder or Cerebra Centre for related characteristics might be seen in children with genetic syndromes and Neurodevelopmental what this might mean for assessment and intervention. This briefing provides Disorders (CNDD) a summary of information presented in a peer reviewed scientific article University of Birmingham published in 20091 and an academic book chapter published in 2011.2 1. What is Autism Spectrum Disorder? Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental disability that occurs in up to 1% of children and adults in the general population3 and up to 40% of individuals within the learning disability population.4 ASD is diagnosed on the basis of observable impairments and behaviours in three core areas (also known as the triad of impairments). These are: 1. impairments in communication and language, 2. impairments in social interaction and social relatedness and, 3. the presence of repetitive behaviours and restricted interests. In children with ASD, difficulties in these three areas are typically evident before the age of three years. ASD is a spectrum condition, which means that while all people with ASD share certain difficulties, there is a great deal of variability in the way in which these difficulties are seen and in their severity. 2. What is the cause of Autism Spectrum Disorder? The specific causes of ASD remain unknown but most studies indicate a biological or genetic cause.5 A high level of heritability (passing within families) of ASD characteristics in families and siblings of affected individuals has been reported.6 However, this is not always the case and there are many individuals with ASD in which there are no familial links to the condition.7 Registered Charity no. -

Chromosomal Disorders

Understanding Genetic Tests and How They Are Used David Flannery,MD Medical Director American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Starting Points • Genes are made of DNA and are carried on chromosomes • Genetic disorders are the result of alteration of genetic material • These changes may or may not be inherited Objectives • To explain what variety of genetic tests are now available • What these tests entail • What the different tests can detect • How to decide which test(s) is appropriate for a given clinical situation Types of Genetic Tests . Cytogenetic . (Chromosomes) . DNA . Metabolic . (Biochemical) Chromosome Test (Karyotype) How a Chromosome test is Performed Medicaldictionary.com Use of Karyotype http://medgen.genetics.utah.e du/photographs/diseases/high /peri001.jpg Karyotype Detects Various Chromosome Abnormalities • Aneuploidy- to many or to few chromosomes – Trisomy, Monosomy, etc. • Deletions – missing part of a chromosome – Partial monosomy • Duplications – extra parts of chromosomes – Partial trisomy • Translocations – Balanced or unbalanced Karyotyping has its Limits • Many deletions or duplications that are clinically significant are not visible on high-resolution karyotyping • These are called “microdeletions” or “microduplications” Microdeletions or microduplications are detected by FISH test • Fluorescence In situ Hybridization FISH fluorescent in situ hybridization: (FISH) A technique used to identify the presence of specific chromosomes or chromosomal regions through hybridization (attachment) of fluorescently-labeled DNA probes to denatured chromosomal DNA. Step 1. Preparation of probe. A probe is a fluorescently-labeled segment of DNA comlementary to a chromosomal region of interest. Step 2. Hybridization. Denatured chromosomes fixed on a microscope slide are exposed to the fluorescently-labeled probe. Hybridization (attachment) occurs between the probe and complementary (i.e., matching) chromosomal DNA. -

ORD Resources Report

Resources and their URL's 12/1/2013 Resource Name: Resource URL: 1 in 9: The Long Island Breast Cancer Action Coalition http://www.1in9.org 11q Research and Resource Group http://www.11qusa.org 1p36 Deletion Support & Awareness http://www.1p36dsa.org 22q11 Ireland http://www.22q11ireland.org 22qcentral.org http://22qcentral.org 2q23.org http://2q23.org/ 4p- Support Group http://www.4p-supportgroup.org/ 4th Angel Mentoring Program http://www.4thangel.org 5p- Society http://www.fivepminus.org A Foundation Building Strength http://www.buildingstrength.org A National Support group for Arthrogryposis Multiplex http://www.avenuesforamc.com Congenita (AVENUES) A Place to Remember http://www.aplacetoremember.com/ Aarons Ohtahara http://www.ohtahara.org/ About Special Kids http://www.aboutspecialkids.org/ AboutFace International http://aboutface.ca/ AboutFace USA http://www.aboutfaceusa.org Accelerate Brain Cancer Cure http://www.abc2.org Accelerated Cure Project for Multiple Sclerosis http://www.acceleratedcure.org Accord Alliance http://www.accordalliance.org/ Achalasia 101 http://achalasia.us/ Acid Maltase Deficiency Association (AMDA) http://www.amda-pompe.org Acoustic Neuroma Association http://anausa.org/ Addison's Disease Self Help Group http://www.addisons.org.uk/ Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma Organization International http://www.accoi.org/ Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma Research Foundation http://www.accrf.org/ Advocacy for Neuroacanthocytosis Patients http://www.naadvocacy.org Advocacy for Patients with Chronic Illness, Inc. http://www.advocacyforpatients.org -

Prader Willi and Angelman Syndrome PCR Tests

Prader Willi and Angelman Syndrome PCR Tests The UNC Hospitals Molecular Genetics Laboratory offers a PCR test for defects of the gene region on chromosome 15 associated with Prader Willi and Angelman syndromes. Molecular basis of the diseases: Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes involve an imprinted region on chromosome 15 where genes are differentially methylated and therefore differentially expressed depending on the parental origin of the chromosome. Besides an imprinting error, gene deletion or uniparental disomy are other mechanisms for loss of gene expression. Prader-Willi syndrome results from absence (or lack of expression) of genes that are normally expressed from the paternal allele, whereas Angelman syndrome is caused by absence (or lack of expression) of genes normally expressed from the maternal allele. These are referred to as “reciprocal syndromes”. Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a common syndromal cause of obesity. Incidence is estimated to be 1:20,000. In infancy PWS manifests with profound hypotonia, mild prenatal growth retardation, poor feeding and failure to thrive. Starting at about 12 to 18 months of age, patients exhibit uncontrolled overeating, and obesity becomes a major diagnostic feature and a major health problem. Other common clinical features include short stature, mild mental retardation, gross motor delay, characteristic facial features and behavioral problems. Deletions in the paternally inherited chromosome 15q11q13 account for approximately 70% of PWS cases. Maternal uniparental disomy (UPD) and imprinting defects in the 15q region are other causes of PWS that are detectable by the new PCR assay. Angelman syndrome (AS) is characterized by severe motor and intellectual retardation, ataxia, absence of speech, hyperactivity, hypotonia and frequent smiling with episodes of unprovoked laughter. -

Neurological Syndromes

Neurological Syndromes J. Gordon Millichap Neurological Syndromes A Clinical Guide to Symptoms and Diagnosis J. Gordon Millichap, MD., FRCP Professor Emeritus of Pediatrics and Neurology Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Chicago, IL, USA Pediatric Neurologist Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago Chicago , IL , USA ISBN 978-1-4614-7785-3 ISBN 978-1-4614-7786-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4614-7786-0 Springer New York Heidelberg Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2013943276 © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Permissions for use may be obtained through RightsLink at the Copyright Clearance Center. Violations are liable to prosecution under the respective Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. -

Angelman Syndrome

Angelman syndrome Description Angelman syndrome is a complex genetic disorder that primarily affects the nervous system. Characteristic features of this condition include delayed development, intellectual disability, severe speech impairment, and problems with movement and balance (ataxia). Most affected children also have recurrent seizures (epilepsy) and a small head size (microcephaly). Delayed development becomes noticeable by the age of 6 to 12 months, and other common signs and symptoms usually appear in early childhood. Children with Angelman syndrome typically have a happy, excitable demeanor with frequent smiling, laughter, and hand-flapping movements. Hyperactivity, a short attention span, and a fascination with water are common. Most affected children also have difficulty sleeping and need less sleep than usual. With age, people with Angelman syndrome become less excitable, and the sleeping problems tend to improve. However, affected individuals continue to have intellectual disability, severe speech impairment, and seizures throughout their lives. Adults with Angelman syndrome have distinctive facial features that may be described as "coarse." Other common features include unusually fair skin with light-colored hair and an abnormal side-to-side curvature of the spine (scoliosis). The life expectancy of people with this condition appears to be nearly normal. Frequency Angelman syndrome affects an estimated 1 in 12,000 to 20,000 people. Causes Many of the characteristic features of Angelman syndrome result from the loss of function of a gene called UBE3A. People normally inherit one copy of the UBE3A gene from each parent. Both copies of this gene are turned on (active) in many of the body's tissues. In certain areas of the brain, however, only the copy inherited from a person's mother (the maternal copy) is active. -

Aarskog Syndrome Parents Support Group

Aarskog Syndrome Parents Support Group http://www.familyvillage.wisc.edu/lib_aars.htm AboutFace USA (For people with facial differences) http://www.aboutfaceusa.org AboutFace International http://www.aboutfaceinternational.org ; http://aboutface.ca/ Abetalipoproteinemia (International) http://www.abetalipoproteinemia.org/ Accord Alliance (Disorders of Sexual Development) http://www.accordalliance.org/ Achalasia Support Groups http://achalasia.us/Support_Groups.html Acid Maltase Deficiency Association http://www.amda-pompe.org/ Acoustic Neuroma Association http://anausa.org/ Addison’s Disease Self Help Group UK http://www.addisons.org.uk/ Adinoid Cystic Carcinoma Organization International http://www.accoi.org/ Adinoid Cystic Carcinoma Research Foundation http://www.accrf.org/ Advocacy for Neuroacanthocytosis Patients http://www.naadvocacy.org/ AIS-DSD Support Group USA (Disorders of Sex Development) http://www.aisdsd.org Ais (Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome) Support Group http://www.aissg.org (UK based) AKU (Alkaptonuria) Society http://www.alkaptonuria.info/ Alagille Syndrome Alliance http://www.alagille.org/ ALS Association (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis) http://www.alsa.org Alopecia Support Group (ASG) http://www.alopeciasupport.org/ Alpha-1 Association (Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency) http://www.alpha1.org/ Alpha-1 Canada http://www.alpha1canada.ca/ Alpha-1 Foundation http://www.alpha-1foundation.org/ Alport Syndrome Foundation http://www.alportsyndrome.org Alstrom Syndrome International http://www.alstrom.org/ Alternating Hemiplegia -

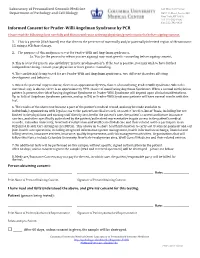

Informed Consent for Prader-Willi Angelman Syndrome By

Laboratory of Personalized Genomic Medicine 630 West 168th Street Department of Pathology and Cell Biology P&S 11th Floor, Room 453 New York, NY 10032 Tel: 212‐305‐9706 Fax: 212‐342‐0420 Informed Consent for Prader‐Willi Angelman Syndrome by PCR Please read the following form carefully and discuss with your ordering physician/genetic counselor before signing consent. 1. This is a genetic (DNA‐based) test that detects the presence of maternally and/or paternally inherited region of chromosome 15, using a PCR‐based assay. 2. The purpose of this analysis is to test for Prader‐Willi and Angelman syndromes. 2a. You (or the person for whom you are signing) may want genetic counseling before signing consent. 3. This is a test for genetic susceptibility (“genetic predisposition”). If the test is positive, you may wish to have further independent testing, consult your physician or have genetic counseling. 4. The condition(s) being tested for are Prader‐Willi and Angelman syndromes, two different disorders affecting development and behavior. 5. When the paternal copy is absent, there is an approximately 99% chance of manifesting Prader‐Willi Syndrome. When the maternal copy is absent, there is an approximately 99% chance of manifesting Angelman Syndrome. When a normal methylation pattern is present, the risk of having Angelman Syndrome or Prader‐Willi Syndrome will depend upon clinical manifestations. Up to 16% of Angelman Syndrome patients, and up to 5% or Prader‐Willi Syndrome patients will have normal results with this test. 6. The results of the above test become a part of the patient’s medical record, and may be made available to individuals/organizations with legal access to the patient’s medical record, on a strict “need‐to‐know” basis, including but not limited to the physicians and nursing staff directly involved in the patient’s care, the patient’s current and future insurance carriers, and other specifically authorized by the patient/authorized representative to gain access to the patient’s medical records. -

Angelman Syndrome Tip Sheet

Angelman Syndrome TIPS AND RESOURCES FOR FAMILIES outstretched. Recent research shows that about half of individuals with Angelman syndrome also will show signs of autism spectrum disorder. Outbursts of laughter are frequent among individuals with Angelman syndrome. Happiness seems to be a constant state, and social smiling may be prevalent. Many individuals are very social and have excellent memories for faces and places. Can Angelman syndrome be treated? Early diagnosis and early intervention is the best treatment. Most individuals with Angelman syndrome make steady developmental progress and do not regress. Those who experience seizures usually need medical care. Physical, occupational, speech, and behavioral therapies contribute What is Angelman syndrome? to improving the quality of life. Water play seems to be Angelman syndrome is a genetic disorder that causes especially appealing to most individuals with Angelman syn- developmental delay and neurological problems. Angelman drome, so swim therapy is often a favorite option. Another syndrome is thought to occur in about 1 in 15,000 births. option may be hippotherapy, a therapeutic approach that The United States and Canada have an estimated 5,000- uses horses instead of typical physical therapy equipment. 10,000 individuals living with Angelman syndrome. It is unlikely that individuals with Angelman syndrome What causes Angelman syndrome? will live independently, but encouraging independence as Individuals with Angelman syndrome usually are missing a much as possible is beneficial. Individuals with Angelman gene on the 15th chromosome called UBE3A. Sometimes syndrome learn best through repetition and structure. Plan UBE3A is present, but is functioning abnormally. well and make learning a game.