History of India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Puducherry from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Coordinates: 11.93°N 79.13°E Puducherry From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Puducherry, formerly known as Pondicherry /ˌpɒndɨˈtʃɛri/, is a Union Territory of Puducherry Union Territory of India formed out of four exclaves of former Pondicherry French India and named after Union Territory the largest Puducherry district. The Tamil name is (Puducherry), which means "New Town".[4] Historically known as Pondicherry (Pāṇṭiccēri), the territory changed its official name to Puducherry (Putuccēri) [5] on 20 September 2006. Seal of Puducherry Contents 1 Geography 1.1 Rivers 2 History 3 French influence 4 Official languages of government 5 Official symbols 6 Government and administration 6.1 Special administration status 7 In culture Location of Puducherry (marked in red) in India 8 Economy Coordinates: 11.93°N 79.13°E 8.1 Output Country India 8.2 Fisheries 8.3 Power Formation 7 Jan 1963 8.4 Tourism Capital and Pondicherry 9 Transport Largest city 9.1 Rail District(s) 4 9.2 Road Government 9.3 Air • Lieutenant A. K. Singh (additional 10 Education Governor charge) [1] 10.1 Pondicherry • Chief N. Rangaswamy (AINRC) University Minister 10.2 Colleges • Legislature (33*seats) 11 See also Unicameral 12 References Area 13 External links • Total 492 km2 (190 sq mi) Population • Total 1,244,464 Geography • Rank 2nd • Density 2,500/km2 (6,600/sq mi) The union territory of Demonym Puducherrian Puducherry consists of four small unconnected districts: Time zone IST (UTC+05:30) Pondicherry, Karaikal and Yanam ISO 3166 IN-PY code on the Bay of Bengal and Mahé on the Arabian Sea. -

Indians As French Citizens in Colonial Indochina, 1858-1940 Natasha Pairaudeau

Indians as French Citizens in Colonial Indochina, 1858-1940 by Natasha Pairaudeau A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of London School of Oriental and African Studies Department of History June 2009 ProQuest Number: 10672932 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672932 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This study demonstrates how Indians with French citizenship were able through their stay in Indochina to have some say in shaping their position within the French colonial empire, and how in turn they made then' mark on Indochina itself. Known as ‘renouncers’, they gained their citizenship by renoimcing their personal laws in order to to be judged by the French civil code. Mainly residing in Cochinchina, they served primarily as functionaries in the French colonial administration, and spent the early decades of their stay battling to secure recognition of their electoral and civil rights in the colony. Their presence in Indochina in turn had an important influence on the ways in which the peoples of Indochina experienced and assessed French colonialism. -

Abstract: the Legacy of the Estado Da India the Portuguese Arrived In

1 Abstract: The Legacy of the Estado da India The Portuguese arrived in India in 1498; yet there are few apparent traces of their presence today, „colonialism‟ being equated almost wholly with the English. Yet traces of Portugal linger ineradicably on the west coast; a possible basis for a cordial re-engagement between India and Portugal in a post-colonial world. Key words: Portuguese, India, colonial legacy, British Empire in India, Estado da India, Goa. Mourning an Empire? Looking at the legacy of the Estado da India. - Dr. Dhara Anjaria 19 December 2011 will mark the fiftieth anniversary of Operation Vijay, a forty-eight hour offensive that ended the Estado da India, that oldest and most reviled of Europe’s ‘Indian Empires.’ This piece remembers and commemorates the five hundred year long Portuguese presence in India that broke off into total estrangement half a hundred years ago, and has only latterly recovered into something close to a detached disengagement.i The colonial legacy informs many aspects of life in the Indian subcontinent, and is always understood to mean the British, the English, legacy. The subcontinent‟s encounter with the Portuguese does not permeate the consciousness of the average Indian on a daily basis. The British Empire is the medium through which the modern Indian navigates the world; he- or she- acknowledges an affiliation to the Commonwealth, assumes a familiarity with Australian mining towns, observes his access to a culturally remote North America made easy by a linguistic commonality, has family offering safe harbours (or increasingly, harbors) from Nairobi to Cape © 2011 The Middle Ground Journal Number 2, Spring 2011 2 Town, and probably watched the handover of Hong Kong with a proprietary feeling, just as though he had a stake in it; after all, it was also once a „British colony.‟ To a lesser extent, but with no lesser fervour, does the Indian acknowledge the Gallicization of parts of the subcontinent. -

The Corporate Evolution of the British East India Company, 1763-1813

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Imperial Venture: The Evolution of the British East India Company, 1763-1813 Matthew Williams Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IMPERIAL VENTURE: THE EVOLUTION OF THE BRITISH EAST INDIA COMPANY, 1763-1813 By MATTHEW WILLIAMS A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2011 Matthew Richard Williams defended this thesis on October 11, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Rafe Blaufarb Professor Directing Thesis Jonathan Grant Committee Member James P. Jones Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Rebecca iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my major professor, Dr. Rafe Blaufarb for his enthusiasm and guidance on this thesis, as well as agreeing to this topic. I must also thank Dr. Charles Cox, who first stoked my appreciation for history. I also thank Professors Jonathan Grant and James Jones for agreeing to participate on my committee. I would be remiss if I forgot to mention and thank Professors Neil Jumonville, Ron Doel, Darrin McMahon, and Will Hanley for their boundless encouragement, enthusiasm, and stimulating conversation. All of these professors taught me the craft of history. I have had many classes with each of these professors and enjoyed them all. -

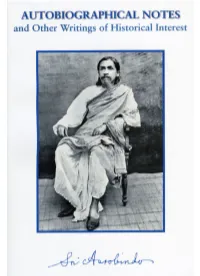

Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest

VOLUME36 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO ©SriAurobindoAshramTrust2006 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest Sri Aurobindo in Pondicherry, August 1911 Publisher’s Note This volume consists of (1) notes in which Sri Aurobindo cor- rected statements made by biographers and other writers about his life and (2) various sorts of material written by him that are of historical importance. The historical material includes per- sonal letters written before 1927 (as well as a few written after that date), public statements and letters on national and world events, and public statements about his ashram and system of yoga. Many of these writings appeared earlier in Sri Aurobindo on Himself and on the Mother (1953) and On Himself: Com- piledfromNotesandLetters(1972). These previously published writings, along with many others, appear here under the new title Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest. Sri Aurobindo alluded to his life and works not only in the notes included in this volume but also in some of the letters he wrote to disciples between 1927 and 1950. Such letters have been included in Letters on Himself and the Ashram, volume 35 of THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO. The autobiographical notes, letters and other writings in- cluded in the present volume have been arranged by the editors in four parts. The texts of the constituent materials have been checked against all relevant manuscripts and printed texts. The Note on the Texts at the end contains information on the people and historical events referred to in the texts. -

Advent of Europeans and Pre-1857 Wars

1498, Vasco Da Gama, Calicut Basic Info First factory @ Calicut by Pedro Alvarez Cabral Important trading centres: Calicut, Cannanore, Kochi 1st Portuguese governor Fransisco Almeida Blue Water Policy: To make Portuguese the master of Indian Ocean real founder of Portuguese power in India Governors Albererque abolition of Sati captured Goa from Sultan of Bijapur shifted capital from Cochin to Goa Nino da Cunha obtained Bassein from Bahadur Shah Portuguese (1498) Introduced Printing Press Contribution Spread Christianity in the Malabar area New Crops- Cashew Nuts, Tobacco, Lady's Finger To promote Christianity and persecute all Muslims Initially quite tolerant towards Hindus, later persecuted them Religious Policy as well Rodolfo Aquaviva and Antonio Monserrate - 1st Jesuit Mission in the court of Akbar No able leader after Alfonso Stiff competition from the Dutch Decline Hostility from natives Discovery of Brazil deviated their attention First factory @ Surat 1600- Elizabeth's Charter to EIC for trade monopoly with the east 1609- Willian Hawkins visited Jahangir's court but couldn't convince him to permit setting up a factory at Surat 1612- Battle of Swally; English forces u/d Thomas Best defeated Portuguese 1613= Jahangir permitted British to set up factory @ English Surat 1632- Golden Farman from Sultan of Golconda Magna Carta for the company exempted from additional customs duty except annual payments as settled 1717- Farrukh Siyar's Farman company could issue "dastaks" for duty free transportation of goods coins minted by company -

Nationalism in French India the Role Played by Pondicherry in The

Nationalism in French India The role played by Pondicherry in the freedom struggle of India does not find mention in the colossal documentation that speaks of the actual struggle on the road to freedom on mainstream India form the colonial yoke. To the credit of Pondicherry tough, writers like A. Ramasamy and others have taken pains to record the contribution of Pondicherrians inside and outside Pondicherry. What emerges is the fact that being in the immediate and convenient vicinity outside British India, Pondicherry developed an identity as an asylum/ safe haven for revolutionaries hunted out of British India, a spring-board for national sentiments of those who took abode therein, and a launching pad for the publication of magazines with nationalistic writings like the Tamil Weekly, India, under editorship of the famous post Subramnia Bharathi. Even the revolutionary Shri Aurobindo Ghosh originally arrived in Pondicherry from Bengal in 1910, to be out of reach of the British Government, Bharathi, Aurobindo Ghosh and V.V.S. Iyer, all three who were outsiders to Pondicherry combined together with some other locally, based patriots to form a society of intellectuals to discuss topics on the theme of ways and means to achieves Indian independence. Other revolutionary names like that of Neelakanta Brahamchari, the editor of vernacular paper Suryodayam, Subramani Siva, Vanchinathan, Madasamy, Deivasigamani Naicker, Bharathidasan, Saigon Chinnaiya, Jaganatha Giramani etc. among others, do find mention for their active sentiments towards the Indian freedom struggle. Others who contributed no less where people like the Gandhi of French India, Rangasamy Naicker and Joseph Xavery Pillai, both of Karaikal, who are also listed for their associations with the then congress leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, and their practice of the Gandhian principles, as also their participation in the Indian Freedom struggle. -

TH"; DUTCH EAS1' INDIA. COMP...Tni' ...Tno MI'sosi<;

TH"; DUTCH EAS1' INDIA. COMP...tNI' ...tNO MI'SOSI<; VERHANDELINGEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR TAAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE DEEL XXXI THE DUTCH E~ST INDIA. COMP~NY .tfND MYSORE 1762·1790 DY JAN VAN LOHUIZEN, Ph. D. 'S·GRAVENHAGE - MARTINUS NUHOFF -1961 CONTENTS Page NOTE ON ABBREVIATIONS, CURRENCY AND WEIGHTS • VI PREFACE • VII INTRODUCTION 1 I THE DUTCH AND HAIDAR AU, 1762-1766 22 IJ FROM ONE EMBASSY TO ANOTHER, 1766-1775 52 III YEARS OF GROWING ESTRANGEMENT AND HOSTILITIES,1775-1781 88 IV WAR WITH THE BRITISH, 1781-1783 • 115 V THE DUTCH AND TIPU SULTAN, 1784-1790 • 135 m~wu~ lM APPENDIX I: THE ORIGIN OF THE NAIR REBELLION OF 1766. 171 APPENDIX Il: THE CONQUEST OF COORG AND CAUCUT IN 1773-1774 177 APPENDIX 111 : THE MYSOREAN-DUTCH AGREEMENT OF 1781 • 180 BIBLIOGRAPHY 183 INDEX 202 MAPS NOTE ON ABBREVIATlONS, CURRENCY AND WEIGH'lS L.f.B. Letters from Batavia (Overgekomen brieven van Batavia) L.f.C. Letters from Ceylon (Overgekomen brieven van Ceylon) L.f.Cor. Letters from Coromande1 (Overgekomen brieven van Coromandel) L.f.M. Letters from Malahar (Overgekomen brieven van Malabar) Set. Dutch Records Madras Selections from the Records of the Madras Government, Dutch Records sJ. secret letter Although rupees and pagodas of different values were in use it will be sufficient for tbe purpose of this study to reckon as follows: 1 pagoda is approximately equivalent to 4 rupees or 8 shillings or 5 guilders. 1 lakh is 100.000. 1 candy is 500 Ibs Dutch or 550 Ibs avoirdupois approximately. PREFACE Only very few Dutch historians have been working in the field of the activities of the Dutch East India Company in India, and their main interest was of ten directed to the period in the 17th century during which Dutch settlements were founded in different parts of the subcontinent. -

Family and Empire Between Britain, British Columbia and India, 1858-1901

Relative Distances: Family and Empire between Britain, British Columbia and India, 1858-1901 Laura Mitsuyo Ishiguro UCL This thesis is submitted for the degree of PhD. I, Laura Mitsuyo Ishiguro, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 1 Abstract This thesis explores the entangled relationship between family and empire in the late-nineteenth-century British Empire. Using the correspondence of British families involved in British Columbia or India between 1858 and 1901, it argues that family letters worked to make imperial lives possible, sustainable and meaningful. This correspondence enabled Britons to come to terms with the personal separations that were necessary for the operation of empire; to negotiate the nature of shifting relationships across imperial distances; and to produce and transmit family forms of colonial knowledge. In these ways, Britons ‘at home’ and abroad used correspondence to navigate the meanings of empire through the prism of family, both in everyday separations and in moments of crisis. Overall, the thesis argues, letter-writing thus positioned the family as a key building block of empire that bound together distant and different places in deeply personal and widely experienced, if also tenuous and anxious, ways. The thesis follows a modular structure, with chapters that explore overlapping but distinct topics of correspondence: food, dress, death and letter- writing itself. Each of these offers a different lens onto the ways in which family correspondence linked Britain with India and British Columbia through intimate channels of affection, obligation, information and representation. -

Shankar Ias Academy Test 7 - Modern India - Ii - Explanation Answer Key

SHANKAR IAS ACADEMY TEST 7 - MODERN INDIA - II - EXPLANATION ANSWER KEY 1. Ans (d) 2. Ans (a) Explanation: Calcutta • Calcutta was home to 5 Nobel Laureates - the most in any Asian Mainland city (apart from Tokyo and Kyoto). Sir Ronald Ross, Rabindranath Tagore, Sir C V Raman, Amartya Sen and Mother Teresa. • Sir Ronald Ross was a British medical doctor who received the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1902 for his work on the transmission of malaria, becoming the first British Nobel laureate, and the first born outside of Europe. He worked in the Indian Medical Service for 25 years. It was during his service that he made the groundbreaking medical discovery. • It is the oldest of all the shipping ports of Indian coastline. Situated on the Hooghly River, it remained the capital for British Empire in India for a very long time. It was situated about 30 km from the coast. 3. Ans (a) Explanation: Indian rhinoceros • The Indian rhinoceros once ranged throughout the entire stretch of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, but excessive hunting and agricultural development reduced their range drastically to 11 sites in northern India and southern Nepal. Moreover, the extent and quality of the rhino's most important habitat, alluvial grassland and riverine forest, is considered to be in decline due to human and livestock encroachment. • The endangered species that live within the Sundarbans and extinct species that used to be include the royal Bengal tigers, estuarine crocodile, northern river terrapins (Batagur baska), olive ridley sea turtles, Gangetic dolphin, ground turtles, hawksbill sea turtles and king crabs (horse shoe). -

A Print Version of All the Papers of January 2010

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 10 : 1 January 2010 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. K. Karunakaran, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. Contents Linguistic Purism and Language Planning in a Multilingual Context L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. 1-95 The Problems of Teaching/Learning Tenses K. R. Vijaya, M.A., M. Phil. and Latha Viswanath, M.A., M.Phil., B.Ed. 96-101 Language and Literature: An Exposition - Papers Presented in the Karunya University National Seminar J. Sundarsingh, Ph.D. 102-106 Similes in Meghduta - The Absolute Craftsmanship in Language Amrita Sharma, Ph.D. 107-118 Culture of the Tamil Society as Portrayed in Ponniyin Selvan Prinkle Queensta. M., M.A., M.Phil. Candidate 119-130 Deconstructing Human Society: An Appreciation of Amitav Ghosh's Sea Of Poppies Ravi Bhushan, Ph.D. & Ms Daisy 131-142 Enabling Students to Interpret Literary Texts Independently by Enhancing their Vocabulary S. Jayalakshmi, M.A., M.Phil. 143-149 Coping with the Problems of Mixed Ability Students Archana Shrivastava, Ph.D. 150-159 Displaced Diasporic Identities - A Case Study of Mordecai Richler's The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz Language in India www.languageinindia.com i 10 : 1 January 2010 Contents List J. Samuel Kirubahar, M.A., M.Phil., B.Ed., Ph.D. and Ms. Beulah Mary Rosalene, M.A., B.Ed., M.Phil. 160-168 English Language Teaching in Developing Countries Error Analysis and Remedial Teaching Methods – An Overview K. -

University of California University of California Los Angeles

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title 19th Century Periodicals of Portuguese India: An Assessment of Documentary Evidence and Indo-Portuguese Identity. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9nm6x7j8 Author Pendse, Liladhar Ramchandra Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California University of California Los Angeles 19th Century Periodicals of Portuguese India: An Assessment of Documentary Evidence and Indo-Portuguese Identity. A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Information Studies by Liladhar Ramchandra Pendse 2012 © copyright by Liladhar Ramchandra Pendse ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION 19th Century Periodicals of Portuguese India: An Assessment of Documentary Evidence and Indo-Portuguese Identity. by Liladhar Ramchandra Pendse Doctor of Philosophy in Information Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Anne J. Gilliland, Chair Portuguese colonial periodicals of 19th century India represent a rich source of information that might be used by scholars in comparative literature, history, post-colonial studies, and other humanities and social sciences-related disciplines. These periodicals are markers of modalities of colonial dominance and the ensuing hybridities that led to formation of the complex Indo-Portuguese identity (-ies) in the 19th century Indian sub-continent. Although the majority of these collections remain in India and Portugal, these periodicals also form a part of extensive South Asia collections held in academic libraries in the United States. These periodicals have often been overlooked as a source of information on the colonial milieu of 19th century India because access to them has been problematic for several reasons.