Scars of Partition William F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding African Armies

REPORT Nº 27 — April 2016 Understanding African armies RAPPORTEURS David Chuter Florence Gaub WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM Taynja Abdel Baghy, Aline Leboeuf, José Luengo-Cabrera, Jérôme Spinoza Reports European Union Institute for Security Studies EU Institute for Security Studies 100, avenue de Suffren 75015 Paris http://www.iss.europa.eu Director: Antonio Missiroli © EU Institute for Security Studies, 2016. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. Print ISBN 978-92-9198-482-4 ISSN 1830-9747 doi:10.2815/97283 QN-AF-16-003-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-9198-483-1 ISSN 2363-264X doi:10.2815/088701 QN-AF-16-003-EN-N Published by the EU Institute for Security Studies and printed in France by Jouve. Graphic design by Metropolis, Lisbon. Maps: Léonie Schlosser; António Dias (Metropolis). Cover photograph: Kenyan army soldier Nicholas Munyanya. Credit: Ben Curtis/AP/SIPA CONTENTS Foreword 5 Antonio Missiroli I. Introduction: history and origins 9 II. The business of war: capacities and conflicts 15 III. The business of politics: coups and people 25 IV. Current and future challenges 37 V. Food for thought 41 Annexes 45 Tables 46 List of references 65 Abbreviations 69 Notes on the contributors 71 ISSReportNo.27 List of maps Figure 1: Peace missions in Africa 8 Figure 2: Independence of African States 11 Figure 3: Overview of countries and their armed forces 14 Figure 4: A history of external influences in Africa 17 Figure 5: Armed conflicts involving African armies 20 Figure 6: Global peace index 22 Figure -

Puducherry from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Coordinates: 11.93°N 79.13°E Puducherry From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Puducherry, formerly known as Pondicherry /ˌpɒndɨˈtʃɛri/, is a Union Territory of Puducherry Union Territory of India formed out of four exclaves of former Pondicherry French India and named after Union Territory the largest Puducherry district. The Tamil name is (Puducherry), which means "New Town".[4] Historically known as Pondicherry (Pāṇṭiccēri), the territory changed its official name to Puducherry (Putuccēri) [5] on 20 September 2006. Seal of Puducherry Contents 1 Geography 1.1 Rivers 2 History 3 French influence 4 Official languages of government 5 Official symbols 6 Government and administration 6.1 Special administration status 7 In culture Location of Puducherry (marked in red) in India 8 Economy Coordinates: 11.93°N 79.13°E 8.1 Output Country India 8.2 Fisheries 8.3 Power Formation 7 Jan 1963 8.4 Tourism Capital and Pondicherry 9 Transport Largest city 9.1 Rail District(s) 4 9.2 Road Government 9.3 Air • Lieutenant A. K. Singh (additional 10 Education Governor charge) [1] 10.1 Pondicherry • Chief N. Rangaswamy (AINRC) University Minister 10.2 Colleges • Legislature (33*seats) 11 See also Unicameral 12 References Area 13 External links • Total 492 km2 (190 sq mi) Population • Total 1,244,464 Geography • Rank 2nd • Density 2,500/km2 (6,600/sq mi) The union territory of Demonym Puducherrian Puducherry consists of four small unconnected districts: Time zone IST (UTC+05:30) Pondicherry, Karaikal and Yanam ISO 3166 IN-PY code on the Bay of Bengal and Mahé on the Arabian Sea. -

French Colonial Reading of Ethnographic Research the Case of the “Desertion” of the Abron King and Its Aftermath*

Ruth Ginio French Colonial Reading of Ethnographic Research The Case of the “Desertion” of the Abron King and its Aftermath* On the night of 17 January 1942, the Governor of Côte-d’Ivoire, Hubert Deschamps, had learned that a traitorous event had transpired—the King of the Abron people Kwadwo Agyeman, regarded by the French as one of their most loyal subjects, had crossed the border to the British-ruled Gold Coast and declared his wish to assist the British-Gaullist war effort. The act stunned the Vichy colonial administration, and it played into the hands of the Gaullists who used this British colony as a propaganda base. Other studies have analysed the causes of the event and its repercussions (Lawler 1997). The purpose of the present article is to use this incident as a case study of a much broader question—one that does not relate exclusively to the Vichy period in French West Africa (hereafter AOF)—namely, the relationship between ethnographic research and French colonial policy, in general, and policy toward the institution of African chiefs, in particular. Studies about the general relationship between anthropology and colo- nialism have used various metaphors and images to characterise it. Anthro- pology has been described as the child of imperialism or as an applied science at the service of colonial powers. The imperialism of the 19th century and the acquisitions of vast territories in different continents boosted the development of modern anthropology (Ben-Ari 1999: 384-385). Anthropological knowledge of Indian societies, for instance, finds some of its origins in the files of administrators, soldiers, policemen and magistrates who sought to control these societies according to the Imperial view of the basic and universal standards of civilisation (Dirks 1997: 185; Asad 1973; Cohn 1980; Coundouriotis 1999; Huggan 1994; Stocking 1991). -

General Agreement on 2K? Tariffs and Trade T£%Ûz'%£ Original: English

ACTION GENERAL AGREEMENT ON 2K? TARIFFS AND TRADE T£%ÛZ'%£ ORIGINAL: ENGLISH CONTRACTING PARTIES The Territorial Application of the General Agreement A PROVISIONAL LIST of Territories to which the Agreement is applied : ADDENDUM Document GATT/CP/l08 contains a comprehensive list of territories to which it is presumed the agreement is being applied by the contracting parties. The first addendum thereto contains corrected entries for Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Finland, Indonesia, Italy, Netherlands, Norway and Sweden. Since that addendum was issued the governments of the countries named below have also replied requesting that the entries concerning them should read as indicated. It will bo appreciated if other governments will notify the Secretariat of their approval of the relevant text - or submit alterations - in order that a revised list may be issued. PART A Territories in respect of which the application of the Agreement has been made effective AUSTRALIA (Customs Territory of Australia, that is the States of New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and Tasmania and the Northern Territory). BELGIUM-LUXEMBOURG (Including districts of Eupen and Malmédy). BELGIAN CONGO RUANDA-URTJimi (Trust Territory). FRANCE (Including Corsica and Islands off the French Coast, the Soar and the principality of Monaco). ALGERIA (Northern Algeria, viz: Alger, Oran Constantine, and the Southern Territories, viz: Ain Sefra, Ghardaia, Touggourt, Saharan Oases). CAMEROONS (Trust Territory). FRENCH EQUATORIAL AFRICA (Territories of Gabon, Middle-Congo, Ubangi»-Shari, Chad.). FRENCH GUIANA (Department of Guiana, including territory of Inini and islands: St. Joseph, Ile Roya, Ile du Diablo). FRENCH INDIA (Pondicherry, Karikal, Yanaon, Mahb.) GATT/CP/l08/Add.2 Pago 2 FRANCE (Cont'd) FRENCH SETTLEMENTS IN OCEANIA (Consisting of Society; Islands, Leeward Islands, Marquozas Archipelago, Tuamotu Archipelago, Gambler Archipelago, Tubuaî Archipelago, Rapa and Clipporton Islands. -

Indians As French Citizens in Colonial Indochina, 1858-1940 Natasha Pairaudeau

Indians as French Citizens in Colonial Indochina, 1858-1940 by Natasha Pairaudeau A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of London School of Oriental and African Studies Department of History June 2009 ProQuest Number: 10672932 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672932 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This study demonstrates how Indians with French citizenship were able through their stay in Indochina to have some say in shaping their position within the French colonial empire, and how in turn they made then' mark on Indochina itself. Known as ‘renouncers’, they gained their citizenship by renoimcing their personal laws in order to to be judged by the French civil code. Mainly residing in Cochinchina, they served primarily as functionaries in the French colonial administration, and spent the early decades of their stay battling to secure recognition of their electoral and civil rights in the colony. Their presence in Indochina in turn had an important influence on the ways in which the peoples of Indochina experienced and assessed French colonialism. -

Abstract: the Legacy of the Estado Da India the Portuguese Arrived In

1 Abstract: The Legacy of the Estado da India The Portuguese arrived in India in 1498; yet there are few apparent traces of their presence today, „colonialism‟ being equated almost wholly with the English. Yet traces of Portugal linger ineradicably on the west coast; a possible basis for a cordial re-engagement between India and Portugal in a post-colonial world. Key words: Portuguese, India, colonial legacy, British Empire in India, Estado da India, Goa. Mourning an Empire? Looking at the legacy of the Estado da India. - Dr. Dhara Anjaria 19 December 2011 will mark the fiftieth anniversary of Operation Vijay, a forty-eight hour offensive that ended the Estado da India, that oldest and most reviled of Europe’s ‘Indian Empires.’ This piece remembers and commemorates the five hundred year long Portuguese presence in India that broke off into total estrangement half a hundred years ago, and has only latterly recovered into something close to a detached disengagement.i The colonial legacy informs many aspects of life in the Indian subcontinent, and is always understood to mean the British, the English, legacy. The subcontinent‟s encounter with the Portuguese does not permeate the consciousness of the average Indian on a daily basis. The British Empire is the medium through which the modern Indian navigates the world; he- or she- acknowledges an affiliation to the Commonwealth, assumes a familiarity with Australian mining towns, observes his access to a culturally remote North America made easy by a linguistic commonality, has family offering safe harbours (or increasingly, harbors) from Nairobi to Cape © 2011 The Middle Ground Journal Number 2, Spring 2011 2 Town, and probably watched the handover of Hong Kong with a proprietary feeling, just as though he had a stake in it; after all, it was also once a „British colony.‟ To a lesser extent, but with no lesser fervour, does the Indian acknowledge the Gallicization of parts of the subcontinent. -

The Corporate Evolution of the British East India Company, 1763-1813

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Imperial Venture: The Evolution of the British East India Company, 1763-1813 Matthew Williams Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IMPERIAL VENTURE: THE EVOLUTION OF THE BRITISH EAST INDIA COMPANY, 1763-1813 By MATTHEW WILLIAMS A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2011 Matthew Richard Williams defended this thesis on October 11, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Rafe Blaufarb Professor Directing Thesis Jonathan Grant Committee Member James P. Jones Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Rebecca iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my major professor, Dr. Rafe Blaufarb for his enthusiasm and guidance on this thesis, as well as agreeing to this topic. I must also thank Dr. Charles Cox, who first stoked my appreciation for history. I also thank Professors Jonathan Grant and James Jones for agreeing to participate on my committee. I would be remiss if I forgot to mention and thank Professors Neil Jumonville, Ron Doel, Darrin McMahon, and Will Hanley for their boundless encouragement, enthusiasm, and stimulating conversation. All of these professors taught me the craft of history. I have had many classes with each of these professors and enjoyed them all. -

History of India

HISTORY OF INDIA VOLUME - 8 View from the Top of the Tiger Gate in Palitana History of India Edited by A. V. Williams Jackson, Ph.D., LL.D., Professor of Indo-Iranian Languages in Columbia University V olum e 8 – From the C lose ofthe S ev en teen th C en tury tothe P resen tTim e By Sir Alfred Comyn Lyall, P.C., K.C.B., D.C.L. 1907 Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar (2018) Introduction by the Editor A connected account of the principal events of Anglo-Indian history from the seventeenth century to the present time is given in this volume. The presentation, though concise, affords a broad view of the rise of British power in the East and makes clear the causes that led to England’ssupremacy. The first chapter reviews in a brief manner the main current of events in India’s development prior to the seventeenth century and forms a convenient supplement to the two preceding volumes, and the succeeding chapters trace the chief historical movements, era by era, down to the present time. The chronological sequence has been indicated throughout the work, but care has been taken not to overload the text with unnecessary dates. Lack of space compelled the author to forego treating several historic incidents, though important, because they have a less direct bearing upon the main theme – the expansion of British dominion in India. Considerations of space also forbade elaborating upon the details of certain well- known events, but room was gained in that way for the important chapter which brings the history down from the time of the Mutiny to the Durbar of King Edward, as well as for the concluding chapter on Britain’swider dominion in Asia. -

Issue 9.2 (2018)

9.2, Autumn 2018 ISSN 2044-4109 (Online) Bulletin of Francophone Postcolonial Studies A Biannual Publication Editor’s Note SARAH ARENS 2 Articles DAVID MURPHY, La Première Guerre Mondiale comme ‘massacre colonial’: 3 Lamine Senghor et les polémiques anticolonialistes dans les années 1920 CHRIS REYNOLDS, État présent: Mai 68 at 50: Beyond the doxa 10 Book Reviews Jean Beaman, Citizen Outsider: Children of North African Immigrants in France 17 ELLEN DAVIS-WALKER Patricia Caillé and Claude Forest (eds.), Regarder des films en Afriques 18 SHEILA PETTY Christopher M. Church, Paradise Destroyed: Catastrophe and Citizenship in the French Caribbean 19 SHANAAZ MOHAMMED Yasser Elhariry, Pacifist Invasions: Arabic, Translation, and the Postfrancophone Lyric 21 JANE HIDDLESTON Emmanuel Jean-François, Poétique de la violence et récits francophones contemporains 22 AUBREY GABEL Mathilde Kang, Francophonie en Orient. Aux Croisements France-Asie (1840-1940) 24 FAY WANRUG SUWANWATTANA David Marriott, Whither Fanon? Studies in the Blackness of Being 26 JANE HIDDLESTON Babacar M’Baye, Black Cosmopolitanism and Anticolonialism: Pivotal Moments 27 DAVID MURPHY Richard C. Parks, Medical Imperialism in French North Africa: Regenerating the Jewish Community of Colonial Tunis 29 REBEKAH VINCE Conference report BETHANY MASON AND ABDELBAQI GHORAB, SFPS PG Study Day 2018: 31 Negotiating Borders in the Francophone World, University of Birmingham Bulletin of Francophone Postcolonial Studies, 9.2 (Autumn 2018) Editor’s note Big shoes to fill. Those were my first thoughts when, at the AGM at the Society’s annual conference in 2017, I took over the editorship of the Bulletin from Kate Marsh. With big shoes come bigger footprints, and tracks, within Francophone Postcolonial Studies. -

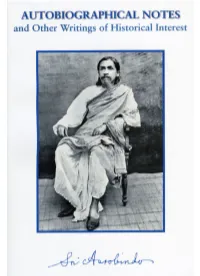

Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest

VOLUME36 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO ©SriAurobindoAshramTrust2006 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest Sri Aurobindo in Pondicherry, August 1911 Publisher’s Note This volume consists of (1) notes in which Sri Aurobindo cor- rected statements made by biographers and other writers about his life and (2) various sorts of material written by him that are of historical importance. The historical material includes per- sonal letters written before 1927 (as well as a few written after that date), public statements and letters on national and world events, and public statements about his ashram and system of yoga. Many of these writings appeared earlier in Sri Aurobindo on Himself and on the Mother (1953) and On Himself: Com- piledfromNotesandLetters(1972). These previously published writings, along with many others, appear here under the new title Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest. Sri Aurobindo alluded to his life and works not only in the notes included in this volume but also in some of the letters he wrote to disciples between 1927 and 1950. Such letters have been included in Letters on Himself and the Ashram, volume 35 of THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO. The autobiographical notes, letters and other writings in- cluded in the present volume have been arranged by the editors in four parts. The texts of the constituent materials have been checked against all relevant manuscripts and printed texts. The Note on the Texts at the end contains information on the people and historical events referred to in the texts. -

Advent of Europeans and Pre-1857 Wars

1498, Vasco Da Gama, Calicut Basic Info First factory @ Calicut by Pedro Alvarez Cabral Important trading centres: Calicut, Cannanore, Kochi 1st Portuguese governor Fransisco Almeida Blue Water Policy: To make Portuguese the master of Indian Ocean real founder of Portuguese power in India Governors Albererque abolition of Sati captured Goa from Sultan of Bijapur shifted capital from Cochin to Goa Nino da Cunha obtained Bassein from Bahadur Shah Portuguese (1498) Introduced Printing Press Contribution Spread Christianity in the Malabar area New Crops- Cashew Nuts, Tobacco, Lady's Finger To promote Christianity and persecute all Muslims Initially quite tolerant towards Hindus, later persecuted them Religious Policy as well Rodolfo Aquaviva and Antonio Monserrate - 1st Jesuit Mission in the court of Akbar No able leader after Alfonso Stiff competition from the Dutch Decline Hostility from natives Discovery of Brazil deviated their attention First factory @ Surat 1600- Elizabeth's Charter to EIC for trade monopoly with the east 1609- Willian Hawkins visited Jahangir's court but couldn't convince him to permit setting up a factory at Surat 1612- Battle of Swally; English forces u/d Thomas Best defeated Portuguese 1613= Jahangir permitted British to set up factory @ English Surat 1632- Golden Farman from Sultan of Golconda Magna Carta for the company exempted from additional customs duty except annual payments as settled 1717- Farrukh Siyar's Farman company could issue "dastaks" for duty free transportation of goods coins minted by company -

Nationalism in French India the Role Played by Pondicherry in The

Nationalism in French India The role played by Pondicherry in the freedom struggle of India does not find mention in the colossal documentation that speaks of the actual struggle on the road to freedom on mainstream India form the colonial yoke. To the credit of Pondicherry tough, writers like A. Ramasamy and others have taken pains to record the contribution of Pondicherrians inside and outside Pondicherry. What emerges is the fact that being in the immediate and convenient vicinity outside British India, Pondicherry developed an identity as an asylum/ safe haven for revolutionaries hunted out of British India, a spring-board for national sentiments of those who took abode therein, and a launching pad for the publication of magazines with nationalistic writings like the Tamil Weekly, India, under editorship of the famous post Subramnia Bharathi. Even the revolutionary Shri Aurobindo Ghosh originally arrived in Pondicherry from Bengal in 1910, to be out of reach of the British Government, Bharathi, Aurobindo Ghosh and V.V.S. Iyer, all three who were outsiders to Pondicherry combined together with some other locally, based patriots to form a society of intellectuals to discuss topics on the theme of ways and means to achieves Indian independence. Other revolutionary names like that of Neelakanta Brahamchari, the editor of vernacular paper Suryodayam, Subramani Siva, Vanchinathan, Madasamy, Deivasigamani Naicker, Bharathidasan, Saigon Chinnaiya, Jaganatha Giramani etc. among others, do find mention for their active sentiments towards the Indian freedom struggle. Others who contributed no less where people like the Gandhi of French India, Rangasamy Naicker and Joseph Xavery Pillai, both of Karaikal, who are also listed for their associations with the then congress leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, and their practice of the Gandhian principles, as also their participation in the Indian Freedom struggle.