Securing the Occupation in East Jerusalem It Increasingly Relies on the Application of Brute Force,5 and This Brute Force Fails to Discourage Palestinian Resistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel and the Middle East News Update

Israel and the Middle East News Update Friday, December 13 Headlines: • Israel Hayom Poll: Center-Left Bloc – 61, Right Wing Bloc - 51, Liberman - 8 • Liberman Backs Pardon for Netanyahu in Exchange for Exit from Politics • Poll: Israelis Prefer a Two State Solution to One State • UK Chief Rabbi: Election Is Over But Worries Over anti-Semitism Remain Commentary: • Ma’ariv: “Netanyahu’s Life’s Work” − By Ben Caspit • TOI: “Why Israel’s 3rd Election Might Not Be Such a Disaster, After All” − By David Horovitz, editor of the Times of Israel S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace 633 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, 5th Floor, Washington, DC 20004 The Hon. Robert Wexler, President ● Yoni Komorov, Editor ● Yehuda Greenfield-Gilat, Associate Editor News Excerpts December 13, 2019 Israel Hayom Poll: Center-Left Bloc – 61, Right Wing Bloc - 51, Liberman - 8 Q: If the Knesset election were held today and Binyamin Netanyahu were Likud chairman, for which party would you vote? Blue and White: 37 Likud: 31 Joint List: 14 Shas: 8 Yisrael Beiteinu: 8 United Torah Judaism: 7 Labor Party-Gesher: 6 New Right: 5 Democratic Union: 4 Q: Who do you think is primarily responsible for the failure to form a government? Binyamin Netanyahu: 43% Avigdor Liberman: 30% Yair Lapid: 6% Benny Gantz: 5% The Haredim: 2% Q: Will the fact that Israel is holding elections for the third time in the span of a year make you change or not change your vote compared with the previous elections? Yes: 13% No: 60% Perhaps: 27% Q: What are the odds that you will vote in the upcoming Knesset election, which will take place in approximately three months? Certain: 59% Good odds: 23% Moderate odds: 3% Poor odds: 15% See also, “Poll shows Gantz’s Blue and White opening 6-seat lead over Netanyahu’s Likud” (Times of Israel) Times of Israel Liberman Backs Pardon for Netanyahu in Exchange for Exit Yisrael Beytenu party leader Avigdor Liberman said Thursday he would back a deal in which Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is allowed to avoid jail in exchange for an agreement to retire from politics. -

Israel and Overseas: Israeli Election Primer 2015 (As Of, January 27, 2015) Elections • in Israel, Elections for the Knesset A

Israel and Overseas: Israeli Election Primer 2015 (As of, January 27, 2015) Elections In Israel, elections for the Knesset are held at least every four years. As is frequently the case, the outgoing government coalition collapsed due to disagreements between the parties. As a result, the Knesset fell significantly short of seeing out its full four year term. Knesset elections in Israel will now be held on March 17, 2015, slightly over two years since the last time that this occurred. The Basics of the Israeli Electoral System All Israeli citizens above the age of 18 and currently in the country are eligible to vote. Voters simply select one political party. Votes are tallied and each party is then basically awarded the same percentage of Knesset seats as the percentage of votes that it received. So a party that wins 10% of total votes, receives 10% of the seats in the Knesset (In other words, they would win 12, out of a total of 120 seats). To discourage small parties, the law was recently amended and now the votes of any party that does not win at least 3.25% of the total (probably around 130,000 votes) are completely discarded and that party will not receive any seats. (Until recently, the “electoral threshold,” as it is known, was only 2%). For the upcoming elections, by January 29, each party must submit a numbered list of its candidates, which cannot later be altered. So a party that receives 10 seats will send to the Knesset the top 10 people listed on its pre-submitted list. -

The Mixed Messages of a Diplomatic Lovefest with Full Talmud Translation

Jewish Federation of NEPA Non-profit Organization 601 Jefferson Ave. U.S. POSTAGE PAID The Scranton, PA 18510 Permit # 184 Watertown, NY Change Service Requested Published by the Jewish Federation of Northeastern Pennsylvania VOLUME X, NUMBER 4 FEBRUARY 23, 2017 Trump and Netanyahu: The mixed messages of a diplomatic lovefest Netanyahu said instead that others, in- ANALYSIS cluding former Vice President Joe Biden, BY RON KAMPEAS At right: Israeli Prime have cautioned him that a state deprived of WASHINGTON (JTA) – One state. Minister Benjamin security control is less than a state. Instead Flexibility. Two states. Hold back on Netanyahu, left, and of pushing back against the argument, he settlements. Stop Iran. President Donald Trump in said it was a legitimate interpretation, but When President Donald Trump met the Oval Office of the White not the only one. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu: House on February 15. That relieves pressure from Net- What a press conference! (Photo by Andrew Harrer/ anyahu’s right flank in Israel, which has But wait. Pool/Getty Images) pressed him to seize the transition from In the Age of Trump, every post-event the Obama administration – which insisted analysis requires a double take. Not so on two states and an end to settlement – much “did he mean what he said?” – he ONE STATE, TWO STATES predecessors have also said that the final to the Trump administration and expand appears to mean it, in real time – but “will At first blush, Trump appeared to headily status must be determined by the Israelis settlement. Now he can go home and say, he mean it next week? Tomorrow? In the embrace the prospect of one state – although and the Palestinians, but also have made truthfully, that he has removed “two states” wee hours, when he tweets?” it’s not clear what kind of single state he clear that the only workable outcome is from the vocabulary. -

The Twentieth Knesset

Unofficial Translation Internal Number: 578022 The Twentieth Knesset Initiators: Knesset Members David Bitan Uri Maklev Yoav Ben-Tzur Bezalel Smotrich Yoav Kish Eli Cohen Sharren Haskel Robert Ilatov Yair Lapid Nava Boker Nissan Slomiansky Avi Dichter Yaakov Peri Meir Cohen Makhlouf “Miki” Zohar Anat Berko Nurit Koren Mickey Levy Aliza Lavie ______________________________________________________ P/20/2808 Bill for the Entry into Israel Law (Amendment – Cancellation of Visa and Permanent Residence Permits of Terrorists and their Families after their Participation in Terrorist Activities) – 2016 [5776] Amendment of Article 11 1. In Article 11 of the Entry into Israel Law of 19521 [5712], the following should be stipulated after sub-section (b): 1 Statutes Book of the [Hebrew] year 5712 [extends from 1 October 1951 until 19 September 1952], Page 146. Unofficial Translation “(c) Without undermining what was mentioned in sub-section (a), the Minister of the Interior is entitled to cancel the visa and permanent residence permit of any person who commits a terrorist act (as defined by this law) against the State of Israel and its citizens; provided that he would not cancel any visa or permanent residence permit before giving the person the chance to plead and state his/her claims before him. (d) Without undermining what was mentioned in sub-section (a), the Minister of the Interior is entitled to cancel the visa or permanent residence permit of the relative of a person who performs a terrorist act or contributes to it (whether through an act or by knowledge) before, during or after the undertaking of that act; provided that the Minister would not cancel any visa or permanent residence permit before giving the terrorist’s relative the chance to plead and state his/her claims before him. -

Israel 2020 Human Rights Report

ISRAEL 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Israel is a multiparty parliamentary democracy. Although it has no constitution, its parliament, the unicameral 120-member Knesset, has enacted a series of “Basic Laws” that enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a “state of emergency,” which has been in effect since 1948. Under the Basic Laws, the Knesset has the power to dissolve itself and mandate elections. On March 2, Israel held its third general election within a year, which resulted in a coalition government. On December 23, following the government’s failure to pass a budget, the Knesset dissolved itself, which paved the way for new elections scheduled for March 23, 2021. Under the authority of the prime minister, the Israeli Security Agency combats terrorism and espionage in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. The national police, including the border police and the immigration police, are under the authority of the Ministry of Public Security. The Israeli Defense Forces are responsible for external security but also have some domestic security responsibilities and report to the Ministry of Defense. Israeli Security Agency forces operating in the West Bank fall under the Israeli Defense Forces for operations and operational debriefing. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security services. The Israeli military and civilian justice systems have on occasion found members of the security forces to have committed abuses. Significant human -

Israel: Background and U.S. Relations in Brief Name Redacted Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs

Israel: Background and U.S. Relations in Brief name redacted Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs February 12, 2018 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R44245 Israel: Background and U.S. Relations in Brief Contents U.S.-Israel Relations: Key Concerns ............................................................................................... 1 Israeli-Palestinian Issues ................................................................................................................. 3 Overview ................................................................................................................................... 3 Assessment ................................................................................................................................ 5 Jerusalem ................................................................................................................................... 6 New U.S. Stance ................................................................................................................. 6 Reactions and Policy Implications ...................................................................................... 7 Regional Security Issues.................................................................................................................. 9 Iran and Its Allies .............................................................................................................. 10 Lebanon-Syria Border Area and Hezbollah ..................................................................... -

Israeli Nonprofits: an Exploration of Challenges and Opportunities , Master’S Thesis, Regis University: 2005)

Israeli NGOs and American Jewish Donors: The Structures and Dynamics of Power Sharing in a New Philanthropic Era Volume I of II A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies S. Ilan Troen, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Eric J. Fleisch May 2014 The signed version of this form is on file in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. This dissertation, directed and approved by Eric J. Fleisch’s Committee, has been accepted and approved by the Faculty of Brandeis University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Malcolm Watson, Dean Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Dissertation Committee: S. Ilan Troen, Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Jonathan D. Sarna, Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Theodore Sasson, Department of International Studies, Middlebury College Copyright by Eric J. Fleisch 2014 Acknowledgements There are so many people I would like to thank for the valuable help and support they provided me during the process of writing my dissertation. I must first start with my incomparable wife, Rebecca, to whom I dedicate my dissertation. Rebecca, you have my deepest appreciation for your unending self-sacrifice and support at every turn in the process, your belief in me, your readiness to challenge me intellectually and otherwise, your flair for bringing unique perspectives to the table, and of course for your friendship and love. I would never have been able to do this without you. -

Are You Coming with a Bulldozer to Silwan?

BOOK REVIEW Abstract Are You Coming A review of two Palestinian guides to Jerusalem and its environs, as with a Bulldozer to well as sites in the West Bank, Gaza and historic Palestine: Wujood: The Silwan? Grassroots Guide to Jerusalem (2019) and Pilgrimage, Sciences and Sufism: Palestinian Guides Islamic Art in the West Bank and Gaza to Jerusalem and Its (2004). The review explores the fate of Palestinian guides to Jerusalem amid Environs the well-financed marketing campaigns Review by Penny Johnson of both the Israeli government and right-wing settler organizations like the Ir David Foundation. Keywords Jerusalem; tourism; travel guides; Silwan; Ir David Foundation; Mount of Olives; Islamic art; pilgrimage. “What should we see?” a diminutive American woman with a very pregnant daughter asked me as I waited at the Amsterdam airport for an Easy Jet flight to Tel Aviv. “Are you on a pilgrimage?” I asked, catching her Texas drawl and equating, perhaps stereotypically, that distinctive accent with Southern Baptist piety. “Oh, yes,” she replied happily, as Wujood: The Grassroots Guide to other members of her family group trailed Jerusalem. 433 pp. Grassroots Al-Quds, into the boarding area and her husband 2019. $40.00 paper. Digital version began handing out sandwiches from the available, see online airport’s McDonald’s. http://www.grassrootsalquds.net/campaigns- “Oh, I love bacon,” the mother projects/wujood-grassroots-guide-jerusalem-0 exclaimed, looking at me. I appreciated Pilgrimage, Sciences and Sufism: her capacity to find happiness even in Islamic Art in the West Bank and Gaza. the crowded boarding area but refrained 253 pp. -

Judging Jerusalem Funding Digs

NEWSFOCUS Hot pots. Shards from Eilat Mazar’s dig in Jerusalem are at the center of the heated debate. Hebrew University in Jerusalem, contends that the discovery bolsters the traditional view that a powerful Jewish king reigned from a substantial city around 1000 B.C.E. “The news is that this huge construction was not built by ancient Canaanites,” she says, referring to the people who lived in the region before the Jews. And she goes a step further, arguing that the site is probably that of David’s palace. Mazar says she will soon publish new radiocarbon dates to back up her claim. But other archaeologists are hes- itant to assign the building’s identity, and some question the dating. The city was “a typical highland village” until a century or so later, says Tel Aviv University archaeolo- gist Israel Finkelstein, whose critique of ancient Jerusalem’s influence has made him a target of scholarly ire (see sidebar, p. 591). That would make the biblical accounts wildly exaggerated, at best. Academic spats about the dating of Iron Age cooking pots are not uncommon, but on March 12, 2012 this one spills over into political and religious disputes as well. “You have similar situations throughout the ancient Near East, but they don’t create the same level of emotion,” says Lawson Younger, an epigrapher at Trinity International University in Deerfield, Illinois. Many nationalist Israelis and devout Chris- tians are eager to prove the accuracy of the www.sciencemag.org stories about David and Solomon, whereas some Palestinians suspect that Jewish- funded excavations aim at legitimizing Israeli control of a city that to Muslims is second only to Mecca. -

Members of Knesset Orly Levi-Abekasis David Amsalem

The 20th Knesset Originators: Members of Knesset Orly Levi-Abekasis David Amsalem David Bitan Ya'akov Margi Karin Elharar Ayelet Nahmias-Verbin Zehava Gal-On Oren Asaf Hazan Merav Michaeli Daniel Atar Ksenia Svetlova Nava Boker Michal Rozin Meirav Ben-Ari Mickey Levy Miki Zohar Meir Cohen Aliza Lavie Law Proposal for the Handling of Harmful Cults – 2015 (פ/proposal 1810/20) Definitions: 1. In this law – A "Harmful Cult" – a group of people, incorporated or not, coming together around an idea or person, in a way that exploitation of a relationship of dependence, authority or mental distress takes place of one or more of its members by the use of methods of control over thought processes and behavioral patterns, acting in an organized, systematic and ongoing fashion while committing felonies which are defined by the laws of the State of Israel as crimes or sexual offenses or severe violence as stated by the Law of the Rights of Victims of Felony – 2001. "The Minister" – The Minister of Welfare and Social Services Head of a Harmful Cult 2. The person who heads a Harmful Cult or a person who manages or organizes the activity in a Harmful Cult will be sentenced to 10 years in prison. Confiscation of Property 3. Should a person be convicted in a felony according to article 2, the court will order, unless it reaches a different conclusion out of special considerations which it will then specify, that in addition to any punishment any property related to the offense and held by said person, under his control or in his bank account, will be confiscated; Said confiscation will be done under the directions of chapters C and E through G as stated by the Law for the Fight against Criminal Organizations – 2003. -

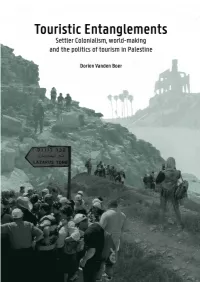

Touristic Entanglements

TOURISTIC ENTANGLEMENTS ii TOURISTIC ENTANGLEMENTS Settler colonialism, world-making and the politics of tourism in Palestine Dorien Vanden Boer Dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of Doctor in the Political and Social Sciences, option Political Sciences Ghent University July 2020 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Christopher Parker iv CONTENTS Summary .......................................................................................................... v List of figures.................................................................................................. vii List of Acronyms ............................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements........................................................................................... xi Preface ........................................................................................................... xv Part I: Routes into settler colonial fantasies ............................................. 1 Introduction: Making sense of tourism in Palestine ................................. 3 1.1. Setting the scene: a cable car for Jerusalem ................................... 3 1.2. Questions, concepts and approach ................................................ 10 1.2.1. Entanglements of tourism ..................................................... 10 1.2.2. Situating Critical Tourism Studies and tourism as a colonial practice ................................................................................. 13 1.2.3. -

Israel: Background and U.S

Israel: Background and U.S. Relations in Brief Jim Zanotti Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs December 22, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44245 Israel: Background and U.S. Relations in Brief Contents U.S.-Israel Relations: Current Status ............................................................................................... 1 Israeli-Palestinian Issues ................................................................................................................. 3 Jerusalem: New U.S. Stance and Implications .......................................................................... 4 Settlements ................................................................................................................................ 7 Regional Security Issues.................................................................................................................. 8 Iran and Its Allies ...................................................................................................................... 9 Lebanon-Syria Border Area and Hezbollah ............................................................................ 10 Palestinians ............................................................................................................................... 11 Domestic Israeli Developments ..................................................................................................... 12 Figures Figure 1. Israel: Map and Basic Facts ............................................................................................