Umi Microfilmed 1990 Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Right Arm Resource Update

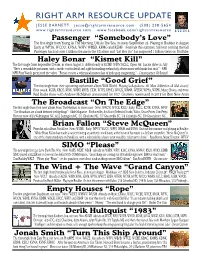

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 6/22/2016 Passenger “Somebody’s Love” The first single from Young As The Morning, Old As The Sea, in stores September 23 Playing in Boulder in August Early at WPYA, WCOO, KVNA, WFIV, WBSD, KFMG and KSMF Festivals this summer, full tour coming this fall Passenger has had over 1 billion streams in the US alone and “Let Her Go” has surpassed 1 billion views on YouTube Haley Bonar “Kismet Kill” The first single from Impossible Dream, in stores August 5 Added early at KCMP, WFIV, KCLC, Open Air Lucius dates in July “She’s a remarkable performer, with a terrific ear for detail and a gift for masking melancholy observations with hooks that stick.” - NPR NPR First Watch premiered the video “Bonar creates a whimsical masterclass of indie-pop songwriting.” - Consequence Of Sound Bastille “Good Grief” The first single from their upcoming sophomore album Wild World Playing Lollapalooza #1 Most Added on all AAA charts! First week: KGSR, KBCO, KINK, WXRV, KRVB, CIDR, WTTS, KPND, WNCS, WRNR, WZEW, WPYA, WXPK, Music Choice and more Red Rocks show with Andrew McMahon announced for 10/7 Grammy nominated in 2015 for Best New Artist The Broadcast “On The Edge” The first single from their new album From The Horizon, in stores now New: WNCW, WYCE, KSLU Early: KCLC, KDTR, KVNA, WFIV “The Broadcast are a band destined for big things” - Glide Magazine Produced by Jim Scott (Tedeschi Trucks, Wilco, Grace Potter, Tom Petty) On tour now: 6/23 Wilmington NC, 6/25 Lexington NC, 7/1 Charlotte NC, 7/7 Greenville SC, 7/8 Columbia SC, 7/9 Greensboro NC.. -

The Power of Heritage to the People

How history Make the ARTS your BUSINESS becomes heritage Milestones in the national heritage programme The power of heritage to the people New poetry by Keorapetse Kgositsile, Interview with Sonwabile Mancotywa Barbara Schreiner and Frank Meintjies The Work of Art in a Changing Light: focus on Pitika Ntuli Exclusive book excerpt from Robert Sobukwe, in a class of his own ARTivist Magazine by Thami ka Plaatjie Issue 1 Vol. 1 2013 ISSN 2307-6577 01 heritage edition 9 772307 657003 Vusithemba Ndima He lectured at UNISA and joined DACST in 1997. He soon rose to Chief Director of Heritage. He was appointed DDG of Heritage and Archives in 2013 at DAC (Department of editorial Arts and Culture). Adv. Sonwabile Mancotywa He studied Law at the University of Transkei elcome to the Artivist. An artivist according to and was a student activist, became the Wikipedia is a portmanteau word combining youngest MEC in Arts and Culture. He was “art” and “activist”. appointed the first CEO of the National W Heritage Council. In It’s Bigger Than Hip Hop by M.K. Asante. Jr Asante writes that the artivist “merges commitment to freedom and Thami Ka Plaatjie justice with the pen, the lens, the brush, the voice, the body He is a political activist and leader, an and the imagination. The artivist knows that to make an academic, a historian and a writer. He is a observation is to have an obligation.” former history lecturer and registrar at Vista University. He was deputy chairperson of the SABC Board. He heads the Pan African In the South African context this also means that we cannot Foundation. -

The Falcon, Volume 89, Issue 1 Sep. 27, 2106

theFalcon Volume 89, Issue 1 Quincy University Tuesday, September 27, 2016 CAMPUS PARKING QU’s David Jacob is in the minor leagues; read more about his success Beware the signs; park with caution DOMINIC MILES STAFF WRITER Students have been faced with a de- - page 12 cline of parking around Quincy Univer- sity’s campus. These no parking zones are on Chestnut, between the streets of 18th Soccer team travels to and 20th and Lind, between 20th and Germany; may be only 22nd street. trip many will take The “No QU Student Parking” signs went up in the middle of last school year, with the hope that students would abide by these signs. Both QU Security and the Quincy Police Department now enforce these signs and charge students $15 for being parked in a spot. Cars are parked along Chestnut Street between 18th and 20th Streets. Quincy aldermen complained on behalf of residents, as the school year Michael Nielson said. “It didn’t cross my unpaid parking tickets. If this continues started with too many students parking in mind that I could get a ticket from park- to happen, security will have to take even front of houses. ing alongside the curb just like everyone more measures than simply giving out “We’ve been working with our al- e l s e .” tickets. dermen to find a balance between being Nielson received a ticket for parking “Any car that continues to park in the - page 10 good neighbors and our own parking parallel on Lind facing east between 20th no parking zones without a QU sticker is needs,” Sam Lathrop, head of QU security, and 22nd. -

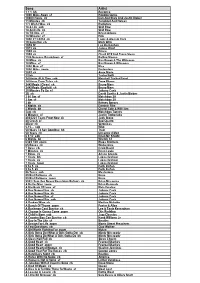

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Karaoke Version Song Book

Karaoke Version Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Hed) Planet Earth 50 Cent Blackout KVD-29484 In Da Club KVD-12410 Other Side KVD-29955 A Fine Frenzy £1 Fish Man Almost Lover KVD-19809 One Pound Fish KVD-42513 Ashes And Wine KVD-44399 10000 Maniacs Near To You KVD-38544 Because The Night KVD-11395 A$AP Rocky & Skrillex & Birdy Nam Nam (Duet) 10CC Wild For The Night (Explicit) KVD-43188 I'm Not In Love KVD-13798 Wild For The Night (Explicit) (R) KVD-43188 Things We Do For Love KVD-31793 AaRON 1930s Standards U-Turn (Lili) KVD-13097 Santa Claus Is Coming To Town KVD-41041 Aaron Goodvin 1940s Standards Lonely Drum KVD-53640 I'll Be Home For Christmas KVD-26862 Aaron Lewis Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow KVD-26867 That Ain't Country KVD-51936 Old Lamplighter KVD-32784 Aaron Watson 1950's Standard Outta Style KVD-55022 An Affair To Remember KVD-34148 That Look KVD-50535 1950s Standards ABBA Crawdad Song KVD-25657 Gimme Gimme Gimme KVD-09159 It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas KVD-24881 My Love, My Life KVD-39233 1950s Standards (Male) One Man, One Woman KVD-39228 I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus KVD-29934 Under Attack KVD-20693 1960s Standard (Female) Way Old Friends Do KVD-32498 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31474 When All Is Said And Done KVD-30097 1960s Standard (Male) When I Kissed The Teacher KVD-17525 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31475 ABBA (Duet) 1970s Standards He Is Your Brother KVD-20508 After You've Gone KVD-27684 ABC 2Pac & Digital Underground When Smokey Sings KVD-27958 I Get Around KVD-29046 AC-DC 2Pac & Dr. -

The Ecology of Puha: Identity, Orientation, and Shifting Perceptions Reflected Through Material Culture and Socioreligious Practice

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2021 THE ECOLOGY OF PUHA: IDENTITY, ORIENTATION, AND SHIFTING PERCEPTIONS REFLECTED THROUGH MATERIAL CULTURE AND SOCIORELIGIOUS PRACTICE Aaron Robert Atencio Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Atencio, Aaron Robert, "THE ECOLOGY OF PUHA: IDENTITY, ORIENTATION, AND SHIFTING PERCEPTIONS REFLECTED THROUGH MATERIAL CULTURE AND SOCIORELIGIOUS PRACTICE" (2021). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11734. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11734 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ECOLOGY OF PUHA: IDENTITY, ORIENTATION, AND SHIFTING PERCEPTIONS REFLECTED THROUGH MATERIAL CULTURE AND SOCIORELIGIOUS PRACTICE By AARON ROBERT ATENCIO Anthropology, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, U.S.A., 2021 Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Philosophy of Anthropology The University of Montana Missoula, MT Official Graduation Date (May 2021) Approved by: Scott Whittenburg, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate -

Karaoke List 2021.Xlsx

Song Artist 1 + 1 bh Beyonce 1000 Miles Away sf Hoodoo Gurus 10000 Hours ck Dan And Shay And Justin Bieber 11 Minutes ck Yungblud And Halsey 17 I Wish I Was ck Radiators 18 & Life sgb Skid Row 18 And Life cb Skid Row 18 Till I Die sf Bryan Adams 18 Wheeler sf Pink 1800 273 8255 ck Logic & Alessia Cara 19 Somethin cb Mark Wills 1959 Sf Lee Kernaghan 1973 cb James Blunt 1999 cb Prince 1999 ck Charli XCX And Troye Sivan 19th Nervous Breakdown sf Rolling Stones 20 Miles ck Ray Brown & The Whispers 20 Miles sf Ray Brown & Whispers 2000 Man sf Kiss 2000 Miles zoom Pretenders 2002 ck Anne Marie 22 bh Taylor Swift 24 Hours At A Time sgb Marshall Tucker Band 24 Hours From Tulsa ck Gene Pitney 24K Magic (Clean) ck Bruno Mars 24K Magic (Explicit) ck Bruno Mars 25 Minutes To Go sf Johnny Cash 2U ck David Guetta & Justin Bieber 3 00 Am sf Matchbox 20 3 Am sf Matchbox 20 3 bh Britney Spears 3 Nights ck Dominic Fike 3 Words bh Cheryl Cole & Will I Am 3am cb Matchbox Twenty 4 Minutes sf Justin Timberlake 4003221 Tears From Now ck Judy Stone 48 Crash sf Suzi Quatro 4Ever ck Veronicas 5.15… sgb Who 50 Ways To Say Goodbye bh Train 50 Years ck Uncanny X Men 6 8 12 sgb Brian Mc Knight 6 Words bh Wretch 32 6345 789 zoom Blues Brothers 65 Roses ck Wolverines 7 Days cb Craig David 7 Minutes ck Dean Lewis 7 Rings ck Ariana Grande 7 Years Bh Lukas Graham 7 Years ck Lukas Graham 7 Years zoom Lukas Graham 9 To 5 cb Dolly Parton 9 To 5 kh Dolly Parton 96 Tears sgb Mysterions 99 Red Balloons cb Nena 99 Red Balloons zoom Nena 999% Sure (Ive Never Been Here Before) cb -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Closer Say It Suicide Squad OST Nothing Has Changed: the Best of 1 the Chainsmokers Feat

05 September 2016 CHART #2050 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Closer Say It Suicide Squad OST Nothing Has Changed: The Best Of 1 The Chainsmokers feat. Halsey 21 Flume feat. Tove Lo 1 Various 21 David Bowie Last week 1 / 5 weeks Gold / Disruptor/SonyMusic Last week 18 / 19 weeks Platinum / FutureClassic/Univers... Last week 2 / 4 weeks Atlantic/Warner Last week 28 / 32 weeks Platinum / Parlophone/Warner Cold Water Ride 25 All Over The World: The Best Of 2 Major Lazer feat. Justin Bieber And... 22 Twenty One Pilots 2 Adele 22 ELO Last week 2 / 6 weeks Gold / Because/Warner Last week 20 / 16 weeks Gold / FueledByRamen/Warner Last week 3 / 41 weeks Platinum x7 / XL/Rhythm Last week 22 / 20 weeks Gold / SonyMusic Let Me Love You This Girl Blonde A/B 3 DJ Snake feat. Justin Bieber 23 Kungs And Cookin' On 3 Burners 3 Frank Ocean 23 Kaleo Last week 3 / 4 weeks Interscope/Universal Last week 23 / 9 weeks KungsMusic/Universal Last week 1 / 2 weeks BoysDon'tCry Last week 15 / 4 weeks Elektra/Warner Heathens Cheap Thrills Poi E: The Story Of Our Song Endless Highway 4 Twenty One Pilots 24 Sia 4 Various 24 Phil Doublet Last week 4 / 11 weeks Gold / Atlantic/Warner Last week 22 / 28 weeks Platinum x2 / Inertia/Rhythm Last week 6 / 4 weeks SonyMusic Last week - / 1 weeks PhilDoublet Sucker For Pain Final Song Encore: Movie Partners Sing Broadw... Revival 5 Lil Wayne, Wiz Khalifa And Imagine... 25 M0 5 Barbra Streisand 25 Selena Gomez Last week 7 / 4 weeks Atlantic/Warner Last week 21 / 7 weeks SonyMusic Last week - / 1 weeks Columbia/SonyMusic Last week 14 / 16 weeks Interscope/Universal Don't Worry Bout It Cool Girl Blurryface Beauty Behind The Madness 6 Kings 26 Tove Lo 6 Twenty One Pilots 26 The Weeknd Last week 5 / 8 weeks Gold / ArchAngel/Warner Last week 29 / 3 weeks Universal Last week 5 / 34 weeks Gold / FueledByRamen/Warner Last week 20 / 40 weeks Republic/Universal One Dance Needed Me Views Cloud Nine 7 Drake feat. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums I'm the One Good Life Divide So Good 1 DJ Khaled Feat

15 May 2017 CHART #2086 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums I'm The One Good Life Divide So Good 1 DJ Khaled feat. Justin Bieber, Quavo... 21 Kehlani And G-Eazy 1 Ed Sheeran 21 Zara Larsson Last week 2 / 2 weeks Epic/SonyMusic/DefJam Last week 23 / 4 weeks WEA/Warner Last week 1 / 10 weeks Platinum x3 / Asylum/Warner Last week 16 / 8 weeks Epic/SonyMusic HUMBLE. Scared To Be Lonely DAMN. Purpose 2 Kendrick Lamar 22 Martin Garrix And Dua Lipa 2 Kendrick Lamar 22 Justin Bieber Last week 1 / 6 weeks Gold / Aftermath/Interscope/Univ... Last week 22 / 14 weeks Gold / Epic/SonyMusic Last week 2 / 4 weeks Aftermath/Interscope/Universal Last week 17 / 78 weeks Platinum x2 / DefJam/Universal Shape Of You Green Light Left Turn At Midnite Morningside 3 Ed Sheeran 23 Lorde 3 Graham Brazier 23 Fazerdaze Last week 3 / 18 weeks Platinum x3 / Asylum/Warner Last week 21 / 10 weeks Platinum / Universal Last week 0 / 1 weeks RipeCoconut/Universal Last week 0 / 2 weeks FlyingNun/FlyingOut Despacito (Remix) Issues 24K Magic 21 4 Luis Fonsi And Daddy Yankee feat. J... 24 Julia Michaels 4 Bruno Mars 24 Adele Last week 6 / 3 weeks Universal Last week 20 / 15 weeks Gold / Republic/Universal Last week 9 / 25 weeks Platinum / Atlantic/Warner Last week 18 / 234 weeks Platinum x13 / XL/Rhythm Options LOYALTY. I Believe Six60 (2) 5 Pitbull feat. Stephen Marley 25 Kendrick Lamar feat. Rihanna 5 Dennis Marsh 25 Six60 Last week 4 / 8 weeks Gold / RCA/SonyMusic Last week 24 / 4 weeks Aftermath/Interscope/Universal Last week 0 / 1 weeks SonyMusic Last week 20 / 115 weeks Platinum / Massive/Universal That's What I Like Castle On The Hill 25 Stoney 6 Bruno Mars 26 Ed Sheeran 6 Adele 26 Post Malone Last week 5 / 13 weeks Platinum / Atlantic/Warner Last week 27 / 18 weeks Platinum / Asylum/Warner Last week 5 / 77 weeks Platinum x9 / XL/Rhythm Last week 21 / 19 weeks Republic/Universal Swalla All Time Low Vera Lynn 100 Starboy 7 Jason DeRulo feat. -

Triple J Hottest 100 of the Decade Voting List: AZ Artists

triple j Hottest 100 of the Decade voting list: A-Z artists ARTIST SONG 360 Just Got Started {Ft. Pez} 360 Boys Like You {Ft. Gossling} 360 Killer 360 Throw It Away {Ft. Josh Pyke} 360 Child 360 Run Alone 360 Live It Up {Ft. Pez} 360 Price Of Fame {Ft. Gossling} #1 Dads So Soldier {Ft. Ainslie Wills} #1 Dads Two Weeks {triple j Like A Version 2015} 6LACK That Far A Day To Remember Right Back At It Again A Day To Remember Paranoia A Day To Remember Degenerates A$AP Ferg Shabba {Ft. A$AP Rocky} (2013) A$AP Rocky F**kin' Problems {Ft. Drake, 2 Chainz & Kendrick Lamar} A$AP Rocky L$D A$AP Rocky Everyday {Ft. Rod Stewart, Miguel & Mark Ronson} A$AP Rocky A$AP Forever {Ft. Moby/T.I./Kid Cudi} A$AP Rocky Babushka Boi A.B. Original January 26 {Ft. Dan Sultan} Dumb Things {Ft. Paul Kelly & Dan Sultan} {triple j Like A Version A.B. Original 2016} A.B. Original 2 Black 2 Strong Abbe May Karmageddon Abbe May Pony {triple j Like A Version 2013} Action Bronson Baby Blue {Ft. Chance The Rapper} Action Bronson, Mark Ronson & Dan Auerbach Standing In The Rain Active Child Hanging On Adele Rolling In The Deep (2010) Adrian Eagle A.O.K. Adrian Lux Teenage Crime Afrojack & Steve Aoki No Beef {Ft. Miss Palmer} Airling Wasted Pilots Alabama Shakes Hold On Alabama Shakes Hang Loose Alabama Shakes Don't Wanna Fight Alex Lahey You Don't Think You Like People Like Me Alex Lahey I Haven't Been Taking Care Of Myself Alex Lahey Every Day's The Weekend Alex Lahey Welcome To The Black Parade {triple j Like A Version 2019} Alex Lahey Don't Be So Hard On Yourself Alex The Astronaut Not Worth Hiding Alex The Astronaut Rockstar City triple j Hottest 100 of the Decade voting list: A-Z artists Alex the Astronaut Waste Of Time Alex the Astronaut Happy Song (Shed Mix) Alex Turner Feels Like We Only Go Backwards {triple j Like A Version 2014} Alexander Ebert Truth Ali Barter Girlie Bits Ali Barter Cigarette Alice Ivy Chasing Stars {Ft. -

Songs by Artist

TOTALLY TWISTED KARAOKE Songs by Artist 37 SONGS ADDED IN SEP 2021 Title Title (HED) PLANET EARTH 2 CHAINZ, DRAKE & QUAVO (DUET) BARTENDER BIGGER THAN YOU (EXPLICIT) 10 YEARS 2 CHAINZ, KENDRICK LAMAR, A$AP, ROCKY & BEAUTIFUL DRAKE THROUGH THE IRIS FUCKIN PROBLEMS (EXPLICIT) WASTELAND 2 EVISA 10,000 MANIACS OH LA LA LA BECAUSE THE NIGHT 2 LIVE CREW CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS ME SO HORNY LIKE THE WEATHER WE WANT SOME PUSSY MORE THAN THIS 2 PAC THESE ARE THE DAYS CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) TROUBLE ME CHANGES 10CC DEAR MAMA DREADLOCK HOLIDAY HOW DO U WANT IT I'M NOT IN LOVE I GET AROUND RUBBER BULLETS SO MANY TEARS THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE UNTIL THE END OF TIME (RADIO VERSION) WALL STREET SHUFFLE 2 PAC & ELTON JOHN 112 GHETTO GOSPEL DANCE WITH ME (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & EMINEM PEACHES AND CREAM ONE DAY AT A TIME PEACHES AND CREAM (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS (DUET) 112 & LUDACRIS DO FOR LOVE HOT & WET 2 PAC, DR DRE & ROGER TROUTMAN (DUET) 12 GAUGE CALIFORNIA LOVE DUNKIE BUTT CALIFORNIA LOVE (REMIX) 12 STONES 2 PISTOLS & RAY J CRASH YOU KNOW ME FAR AWAY 2 UNLIMITED WAY I FEEL NO LIMITS WE ARE ONE 20 FINGERS 1910 FRUITGUM CO SHORT 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 21 SAVAGE, OFFSET, METRO BOOMIN & TRAVIS SIMON SAYS SCOTT (DUET) 1975, THE GHOSTFACE KILLERS (EXPLICIT) SOUND, THE 21ST CENTURY GIRLS TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME 21ST CENTURY GIRLS 1999 MAN UNITED SQUAD 220 KID X BILLEN TED REMIX LIFT IT HIGH (ALL ABOUT BELIEF) WELLERMAN (SEA SHANTY) 2 24KGOLDN & IANN DIOR (DUET) WHERE MY GIRLS AT MOOD (EXPLICIT) 2 BROTHERS ON 4TH 2AM CLUB COME TAKE MY HAND