Understanding Artist Development: How Do Producers Support the Development of Artists Through the Production Process?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Puma Kylie Rihanna 1

Buzz Queens Why Rihanna and Kylie Jenner are critical to Puma’s ambitious new women’s push. By Sheena Butler-Young GE CHINSEE R O E S: G R THE O L AL AND; R B F O Y S E T R U O C : BU AM J OCK; ST R SHUTTE X Behind S: LEPORE: RE the scenes ofO a recent FentyOT design meetingPH ver Easter weekend, why Puma is making the trendset- are nothing new, but the German Rihanna was relishing ting songstress a cornerstone of its footwear-and-apparel maker’s col- a rare few hours of business strategy. laborations with two of pop culture’s O downtime in New But the brand isn’t stopping there. most influential women are not of Last week, the highly anticipated the garden variety. from her Anti World Tour. Scores sneaker from Puma’s campaign with Rihanna, Puma’s women’s creative of paparazzi snapped flicks of the Kylie Jenner hit stores, fueling a new director since December 2014, and UMA P star as she ran errands in a black wave of buzz after the queen of social Kylie Jenner, the brand’s newest F O Vetements hoodie and fur slides media teased her partnership for the ambassador, represent a strategic Y S E T from her Fenty x Puma collection. past month on Instagram. R U O Make no mistake about it: Puma to the women’s market in an unprec- C S: Rihanna’s every fashion move is a is serious about girl power. edented way. O OT statement for the masses. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Financing Music Labels in the Digital Era of Music: Live Concerts and Streaming Platforms

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLS\7-1\HLS101.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-MAR-16 12:46 Financing Music Labels in the Digital Era of Music: Live Concerts and Streaming Platforms Loren Shokes* In the age of iPods, YouTube, Spotify, social media, and countless numbers of apps, anyone with a computer or smartphone readily has access to millions of hours of music. Despite the ever-increasing ease of delivering music to consumers, the recording industry has fallen victim to “the disease of free.”1 When digital music was first introduced in the late 1990s, indus- try experts and insiders postulated that it would parallel the introduction and eventual mainstream acceptance of the compact disc (CD). When CDs became publicly available in 1982,2 the music industry experienced an un- precedented boost in sales as consumers, en masse, traded in their vinyl records and cassette tapes for sleek new compact discs.3 However, the intro- duction of MP3 players and digital music files had the opposite effect and the recording industry has struggled to monetize and profit from the digital revolution.4 The birth of the file sharing website Napster5 in 1999 was the start of a sharp downhill turn for record labels and artists.6 Rather than pay * J.D. Candidate, Harvard Law School, Class of 2017. 1 See David Goldman, Music’s Lost Decade: Sales Cut in Half, CNN Money (Feb. 3, 2010), available at http://money.cnn.com/2010/02/02/news/companies/napster_ music_industry/. 2 See The Digital Era, Recording History: The History of Recording Technology, available at http://www.recording-history.org/HTML/musicbiz7.php (last visited July 28, 2015). -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS December 4, 1973 Port on S

39546 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS December 4, 1973 port on S. 1443, the foreign aid author ADJOURNMENT TO 11 A.M. Joseph J. Jova, of Florida, a Foreign Serv ization bill. ice officer of the class of career minister, to Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. Presi be Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipo There is a time limitaiton thereon. dent, if there be no further business to tentiary of the United States of America to There will be at least one yea-and-nay come before the Senate, I move, in ac Mexico. vote, I am sure, on the adoption of the cordance with the previous order, that Ralph J. McGuire, of the District of Colum. bia, a Foreign Service officer of class 1, to be conference report, and there may be the Senate stand in adjournment until Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipoten other votes. the hour of 11 o'clock a.m. tomorrow. t iary cf the United States of America to the On the disposition of the conference The motion was agreed to; and at 6: 45 Republic of Mali. report on the foreign aid authorization p.m., the Senate adjourned until tomor Anthony D. Marshall, of New York, to be row, Wednesday, December 5, 1973, at Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipoten bill, S. 1443, the Senate will take up tiary of the United States of America to the Calendar Order No. 567, S. 1283, the so lla.m. Republic of Kenya. called energy research and development Francis E. Meloy, Jr., of the District of bill. I am sure there will be yea and Columbia, a Foreign Service officer of the NOMINATIONS class of career minister, to be Amb1ssador nay votes on amendments thereto to Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the morrow. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Redalyc.School in the Era of the Internet

Educación y Educadores ISSN: 0123-1294 [email protected] Universidad de La Sabana Colombia Gofron, Beata School in the Era of the Internet Educación y Educadores, vol. 17, núm. 1, enero-abril, 2014, pp. 171-180 Universidad de La Sabana Cundinamarca, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=83430693009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative School in the Era of the Internet Beata Gofron Akademia Polonijna, Polonia [email protected] Introduction School systems are challenged by today’s quickly changing world with new and com- plicated problems. We live in an era marked by an explosion of information, as illustrated by the fact that the amount of information doubles every year. The cultural change of a revolutionary nature we are now observing, one element of which is development of the Internet towards the Web 3.0 model, is associated with depletion the culture of writing and the cognitive apparatus associated with it; that is, cause and eff ect thinking, linear understanding of time, and an objectivist understanding of the world. The omnipresent electronic media, which use an entire range of audio-visual means of communication, are main “production techniques” of culture, including the current visual culture. They consti- tute the context in which schools function and, at the same time, they pose a considerable risk to them. The computer is almost as common today as a wristwatch, and the owner has immediate access, at any time, to all contents and services in all forms that are available on the Internet. -

Christine Belden

An Interview with Christine Belden at The Historical Society of Missouri St. Louis Research Center, St. Louis, Missouri 29 December 2014 interviewed by Dr. Blanche M. Touhill transcribed by Valerie Leri and edited by Josephine Sporleder Oral History Program The State Historical Society of Missouri Collection S1207 Women as Change Agents DVD 94 © The State Historical Society of Missouri NOTICE 1) This material may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. Code). It may not be cited without acknowledgment to the Western Historical Manuscript Collection, a Joint Collection of the University of Missouri and the State Historical Society of Missouri Manuscripts, Columbia, Missouri. Citations should include: [Name of collection] Project, Collection Number C4020, [name of interviewee], [date of interview], Western Historical Manuscript Collection, Columbia, Missouri. 2) Reproductions of this transcript are available for reference use only and cannot be reproduced or published in any form (including digital formats) without written permission from the Western Historical Manuscript Collection. 3) Use of information or quotations from any [Name of collection] Collection transcript indicates agreement to indemnify and hold harmless the University of Missouri, the State Historical Society of Missouri, their officers, employees, and agents, and the interviewee from and against all claims and actions arising out of the use of this material. For further information, contact: The State Historical Society of Missouri, St. Louis Research Center, 222 Thomas Jefferson Library, One University Blvd., St. Louis, MO 63121 (314) 516-5119 © The State Historical Society of Missouri PREFACE The interview was taped on a placed on a tripod. There are periodic background sounds but the recording is of generally high quality. -

The Music Industry and the Fleecing of Consumer Culture

The Music Industry: Demarcating Rhyme from Reason and the Fleecing of Consumer Culture I. Introduction The recording industry has a long history rooted deep in technological achievement and social undercurrents. In place to support such an infrastructure, is a lengthy list of technological advancements, political connections, lobbying efforts, marketing campaigns, and lawsuits. Ever since the early 20th century, record labels have embarked on a perpetual campaign to strengthen their control over recording artists and those technologies and distribution channels that fuel the success of such artists. As evident through the current draconian recording contracts currently foisted on artists, this campaign has often resulted in success. However, the rise of MTV, peer-to-peer file sharing networks, and even radio itself also proves that the labels have suffered numerous defeats. Unfortunately, most music listeners in the world have remained oblivious to the business practices employed by the recording industry. As long as the appearance of artistic freedom exists, as reinforced through the media, most consumers have typically been content to let sleeping dogs lie. Such a relaxed viewpoint, however, has resulted in numerous policies that have boosted industry profits at the expense of consumer dollars. Only when blatant coercion has occurred, as evidenced through the payola scandals of the 1950s, does the general public react in opposition to such practices. Ironically though, such outbursts of conscience have only served to drive payola practices further underground—hidden behind co-operative advertising agreements and outside promotion consultants. The advent of the Internet in the last decade, however, has thrown the dynamics of the recording industry into a state of disarray. -

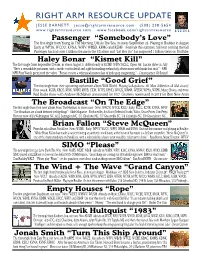

Right Arm Resource Update

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 6/22/2016 Passenger “Somebody’s Love” The first single from Young As The Morning, Old As The Sea, in stores September 23 Playing in Boulder in August Early at WPYA, WCOO, KVNA, WFIV, WBSD, KFMG and KSMF Festivals this summer, full tour coming this fall Passenger has had over 1 billion streams in the US alone and “Let Her Go” has surpassed 1 billion views on YouTube Haley Bonar “Kismet Kill” The first single from Impossible Dream, in stores August 5 Added early at KCMP, WFIV, KCLC, Open Air Lucius dates in July “She’s a remarkable performer, with a terrific ear for detail and a gift for masking melancholy observations with hooks that stick.” - NPR NPR First Watch premiered the video “Bonar creates a whimsical masterclass of indie-pop songwriting.” - Consequence Of Sound Bastille “Good Grief” The first single from their upcoming sophomore album Wild World Playing Lollapalooza #1 Most Added on all AAA charts! First week: KGSR, KBCO, KINK, WXRV, KRVB, CIDR, WTTS, KPND, WNCS, WRNR, WZEW, WPYA, WXPK, Music Choice and more Red Rocks show with Andrew McMahon announced for 10/7 Grammy nominated in 2015 for Best New Artist The Broadcast “On The Edge” The first single from their new album From The Horizon, in stores now New: WNCW, WYCE, KSLU Early: KCLC, KDTR, KVNA, WFIV “The Broadcast are a band destined for big things” - Glide Magazine Produced by Jim Scott (Tedeschi Trucks, Wilco, Grace Potter, Tom Petty) On tour now: 6/23 Wilmington NC, 6/25 Lexington NC, 7/1 Charlotte NC, 7/7 Greenville SC, 7/8 Columbia SC, 7/9 Greensboro NC.. -

The Power of Heritage to the People

How history Make the ARTS your BUSINESS becomes heritage Milestones in the national heritage programme The power of heritage to the people New poetry by Keorapetse Kgositsile, Interview with Sonwabile Mancotywa Barbara Schreiner and Frank Meintjies The Work of Art in a Changing Light: focus on Pitika Ntuli Exclusive book excerpt from Robert Sobukwe, in a class of his own ARTivist Magazine by Thami ka Plaatjie Issue 1 Vol. 1 2013 ISSN 2307-6577 01 heritage edition 9 772307 657003 Vusithemba Ndima He lectured at UNISA and joined DACST in 1997. He soon rose to Chief Director of Heritage. He was appointed DDG of Heritage and Archives in 2013 at DAC (Department of editorial Arts and Culture). Adv. Sonwabile Mancotywa He studied Law at the University of Transkei elcome to the Artivist. An artivist according to and was a student activist, became the Wikipedia is a portmanteau word combining youngest MEC in Arts and Culture. He was “art” and “activist”. appointed the first CEO of the National W Heritage Council. In It’s Bigger Than Hip Hop by M.K. Asante. Jr Asante writes that the artivist “merges commitment to freedom and Thami Ka Plaatjie justice with the pen, the lens, the brush, the voice, the body He is a political activist and leader, an and the imagination. The artivist knows that to make an academic, a historian and a writer. He is a observation is to have an obligation.” former history lecturer and registrar at Vista University. He was deputy chairperson of the SABC Board. He heads the Pan African In the South African context this also means that we cannot Foundation. -

Exhibit O-137-DP

Contents 03 Chairman’s statement 06 Operating and Financial Review 32 Social responsibility 36 Board of Directors 38 Directors’ report 40 Corporate governance 44 Remuneration report Group financial statements 57 Group auditor’s report 58 Group consolidated income statement 60 Group consolidated balance sheet 61 Group consolidated statement of recognised income and expense 62 Group consolidated cash flow statement and note 63 Group accounting policies 66 Notes to the Group financial statements Company financial statements 91 Company auditor’s report 92 Company accounting policies 93 Company balance sheet and Notes to the Company financial statements Additional information 99 Group five year summary 100 Investor information The cover of this report features some of the year’s most successful artists and songwriters from EMI Music and EMI Music Publishing. EMI Music EMI Music is the recorded music division of EMI, and has a diverse roster of artists from across the world as well as an outstanding catalogue of recordings covering all music genres. Below are EMI Music’s top-selling artists and albums of the year.* Coldplay Robbie Williams Gorillaz KT Tunstall Keith Urban X&Y Intensive Care Demon Days Eye To The Telescope Be Here 9.9m 6.2m 5.9m 2.6m 2.5m The Rolling Korn Depeche Mode Trace Adkins RBD Stones SeeYou On The Playing The Angel Songs About Me Rebelde A Bigger Bang Other Side 1.6m 1.5m 1.5m 2.4m 1.8m Paul McCartney Dierks Bentley Radja Raphael Kate Bush Chaos And Creation Modern Day Drifter Langkah Baru Caravane Aerial In The Backyard 1.3m 1.2m 1.1m 1.1m 1.3m * All sales figures shown are for the 12 months ended 31 March 2006. -

Eminem 1 Eminem

Eminem 1 Eminem Eminem Eminem performing live at the DJ Hero Party in Los Angeles, June 1, 2009 Background information Birth name Marshall Bruce Mathers III Born October 17, 1972 Saint Joseph, Missouri, U.S. Origin Warren, Michigan, U.S. Genres Hip hop Occupations Rapper Record producer Actor Songwriter Years active 1995–present Labels Interscope, Aftermath Associated acts Dr. Dre, D12, Royce da 5'9", 50 Cent, Obie Trice Website [www.eminem.com www.eminem.com] Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born October 17, 1972),[1] better known by his stage name Eminem, is an American rapper, record producer, and actor. Eminem quickly gained popularity in 1999 with his major-label debut album, The Slim Shady LP, which won a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. The following album, The Marshall Mathers LP, became the fastest-selling solo album in United States history.[2] It brought Eminem increased popularity, including his own record label, Shady Records, and brought his group project, D12, to mainstream recognition. The Marshall Mathers LP and his third album, The Eminem Show, also won Grammy Awards, making Eminem the first artist to win Best Rap Album for three consecutive LPs. He then won the award again in 2010 for his album Relapse and in 2011 for his album Recovery, giving him a total of 13 Grammys in his career. In 2003, he won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Lose Yourself" from the film, 8 Mile, in which he also played the lead. "Lose Yourself" would go on to become the longest running No. 1 hip hop single.[3] Eminem then went on hiatus after touring in 2005.