Tax Advisors and Conflicted Citizens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retail Industry Audit Technique Guide

Retail Industry Audit Technique Guide NOTE: This guide is current through the publication date. Since changes may have occurred after the publication date that would affect the accuracy of this document, no guarantees are made concerning the technical accuracy after the publication date. All references to code sections are to the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) unless otherwise specified. Publication Date: February 2009 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Description of the Retail Industry ................................................................................................ 5 Purpose for the Audit Technique Guide .................................................................................................... 5 Description of the Retailer ......................................................................................................................... 5 What Retailers Do ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Demographics of the Retail Industry ......................................................................................................... 5 Retail Entities ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Useful Retail Web Sites ............................................................................................................................. 6 Unique General Industry Terminology ...................................................................................................... -

The Legal Responsibilities of the Person Preparing Tax Returns and Furnishing Tax Advice and Reliance Upon Advice of Counsel Louis L

Marquette Law Review Volume 46 Article 3 Issue 3 Winter 1962-1963 The Legal Responsibilities of the Person Preparing Tax Returns and Furnishing Tax Advice and Reliance Upon Advice of Counsel Louis L. Meldman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Louis L. Meldman, The Legal Responsibilities of the Person Preparing Tax Returns and Furnishing Tax Advice and Reliance Upon Advice of Counsel, 46 Marq. L. Rev. 313 (1963). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol46/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LEGAL RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE PERSON PREPARING THE TAX RETURNS AND FURNISHING TAX ADVICE AND RELIANCE UPON ADVICE OF COUNSEL Louis L. MELDMAN** The preparation of income tax returns and the furnishing of tax ad- vice and assistance by the tax practitioner results in many responsibili- ties. The practitioner has a duty first, to his client, the taxpayer. Sec- ondly, he has a duty to the government, the treasury department. And, finally, he has a duty to society to aid in the administration of justice. All of his actions must, in the last analysis, be guided by his own con- science.' RESPONSIBILITY TO THE CLIENT, THE TAXPAYER The attorney, C.P.A., or the accountant has a responsibility to his client. -

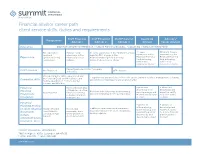

CAREER PATH Client Service Skills, Duties and Requirements

FINANCIAL ADVISOR CAREER PATH Client service skills, duties and requirements Staff Financial Staff Financial Staff Financial Associate Advisor / Paraplanner Advisor I Advisor II Advisor III Advisor Senior Advisor Education Bachelor’s Degree (preferably in Financial Planning, Business, Accounting, Finance or related field) 4+ years’ Minimum 5 years’ 3+ years’ experience in the Financial No experience At least 1 year experience in the experience in the Services industry OR 1–2 years in the required experience in the Financial Planning Financial Planning Experience Financial Planning field delivering advice (prefer internship Financial Services field delivering field delivering and services to clients OR any of the experience) industry advice and advice and following: CFA, CPA, JD services to clients services to clients Not Required Enrolled in CFP® program or licensee CFP® required CFP® License Strong computer skills, experienced and + experienced and proficient in portfolio management software (e.g. Portfolio Center), Computer skills proficient in Excel and Word, basic and contact management software (e.g. Salesforce, Junxure), and document management routine operation of portfolio, contact, software (e.g. Worldox) and document management software Financial + proficient + advanced describing client knowledge and Planning Basic understanding Financial Planning Proficient with data entry and reviewing report package and expertise, ability software and data entry process and understanding client report package Projections Monte Carlo analysis -

The Decline in Tax Adviser Professionalism in American Society

Fordham Law Review Volume 84 Issue 6 Article 14 2016 The Decline in Tax Adviser Professionalism in American Society John S. Dzienkowski University of Texas School of Law Robert J. Peroni University of Texas School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation John S. Dzienkowski and Robert J. Peroni, The Decline in Tax Adviser Professionalism in American Society, 84 Fordham L. Rev. 2721 (2016). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol84/iss6/14 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DECLINE IN TAX ADVISER PROFESSIONALISM IN AMERICAN SOCIETY John S. Dzienkowski* & Robert J. Peroni** INTRODUCTION The United States faces a tax-avoidance crisis that seriously undermines the integrity and effectiveness of the federal income tax system1 and creates a significant tax revenue gap.2 Some tax practitioners and some prominent law and accounting firms have participated in creating and intensifying this crisis.3 Yet, more than a century after the enactment of the modern federal income tax statute, academics, tax lawyers, and accountants continue to debate the appropriate role of the tax practitioner in the tax system. This vigorous discussion has involved many of the leading tax advisers and academic commentators of their time.4 Many of these advisers and * Dean John F. -

Tax Audits in Germany: a Primer and a Plan

Tax Audits in Germany: a Primer and a Plan ROSEMARIE A. RHINES, SCOTT M. BENNETT, AND SILKE BACHT* I. Introduction In Germany, as in most other countries, taxpayers become anxious the moment the rev- enue authority starts an audit. Regardless of whether the taxpayer is German or foreign, neither one looks forward to an audit. Foreign corporations face a bigger challenge, how- ever, because taxes, particularly international taxes, generally are managed by the parent company's tax department, very often with little involvement by the tax advisors of the various subsidiary companies other than the preparation of year-end financial statements and in dealings with the local tax authorities. Herein lies the dilemma: the tax department of the parent company must be "in charge," but it may not know or have experience with the foreign tax laws and regulations affecting the various subsidiaries, familiarity with foreign languages and mentalities, and all the other aspects that can be described as "insight" or "insider knowledge." This dilemma is worsened by tight budgets, shortages of qualified support staff, and the frictions that often arise between tax advisors and business people, who often see the work of the "tax guys" as interfering with their creativity and freedom. Establishing and balancing the roles of the local and non-local tax departments is the major challenge when it comes to dealing professionally with a foreign tax audit. Generally speaking, the in-house tax department can only lose. Even if a favorable tax settlement is reached, local management often feels inconvenienced by the presence of the parent com- pany's advisors and is only relieved when the audit is over because it means that the "tax guys" will finally go away and let the local company get back to business. -

Auditor Tax Advisory Services and Clients' Tax Avoidance

Auditor Tax Advisory Services and Clients’ Tax Avoidance: Do Auditors Draw a Line in the Sand for Tax Advisory Services? Wayne L. Nesbitt Broad College of Business Michigan State University [email protected] Anh Persson Broad College of Business Michigan State University [email protected] Joanna Shaw Broad College of Business Michigan State University [email protected] October 2018 Acknowledgments: We are thankful for the support and guidance of Edmund Outslay and helpful comments from James Anderson, Michelle Nessa, Preetika Joshi (discussant), Sarah Stuber, Dan Wangerin and workshop participants at Michigan State University, the 8th EIASM Conference on Current Research in Taxation, and the 2018 AAA Midwest Region Meeting. We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Eli Broad College of Business at Michigan State University. Joanna Shaw also acknowledges the generous support from the Grant Thornton Doctoral Fellowship. All errors are our own. Auditor Tax Advisory Services and Clients’ Tax Avoidance: Do Auditors Draw a Line in the Sand for Tax Advisory Services? Abstract We investigate whether current PCAOB regulations on the prohibition of the provision of aggressive tax strategies to publicly-listed clients, limits the association between auditor- provided tax services (APTS) and clients’ level of tax avoidance. A resurgence of consultancy services as well as incidents of audit firms’ involvement in clients’ tax aggressive activities have reignited concerns about the provision of non-audit services. Using non-linear and quartile regressions, we document a negative but declining association between tax fees paid and clients’ effective tax rates (ETR). Further, we find evidence that the association becomes positive for the most tax aggressive clients. -

Guide to Certifications for Accounting, Finance and Operations Management Table of Contents

Guide to Certifications For Accounting, Finance and Operations Management Table of Contents About the Guide . 1 The Value of Certifications . 2 Certification Descriptions . 3 Public Accounting . 3 Corporate Accounting . 4 Government . 5 Banking and Financial Services . 6 Personal Financial Management . 7 Audit, Fraud and Risk Management . 7 Operations Management . 9 Tax . .10 Information Technology . .11 Credit . 11 Payroll . .12 Certification Descriptions: Canada . 13 Directory of Accrediting Organizations . 15 Index of Certifications . 21 The Leading Resource . 23 About the Company . 24 ii Guide to Certifications Robert Half About the Guide The Guide to Certifications provides an overview of a wide range of professional designations in the fields of accounting, finance and operations management. Descriptions are based on publicly available information provided by professional associations and other accreditation groups. Contact information for these organizations is listed on Pages 15-20. The Guide to Certifications is published for informational purposes only and is provided without any warranty or guarantee. Certification requirements are changing continually. Certification seekers should always contact the sponsoring organization to verify requirements and obtain the most current information. Most certifications require application and examination fees. Continuing education is almost always necessary to maintain certifications, and fees may be charged to renew them. 1 Guide to Certifications Robert Half The Value of Certifications Corporate governance reforms, an increasingly global business environ- ment and rapidly changing technologies have heightened the demand for accounting and finance professionals who possess advanced skills and have demonstrated their expertise and commitment to ongoing education by earning professional designations. Maintaining industry-recognized accreditations can provide numerous benefits, including improved career prospects and enhanced earning power. -

Tax & Legal Services

Tax & Legal Services kpmg.sk KPMG in Slovakia 3 | Tax and Legal Services Clear, unique, innovative and committed to serve our clients. Tax & Legal Services of KPMG. Tax and Legal Services | 4 Tax & Legal Services The Slovak legislative environment adapts rapidly as the economy changes to adjust to current economic trends and EU requirements. In addition to new or amended legislation, there are significant changes in the interpretation of existing regulations. In these circumstances, effective advice and innovative planning can give your business the competitive advantage. Our tax and legal practice shares the same core KPMG values of clarity, excellence, innovation and, most of all, client service. We offer a range of domestic business and personal services designed to meet the needs of your business, regardless of its size. Because we know how complex tax and legal matters can be, we make it our business to stay abreast of new laws, policies, accounting and commercial principles, and international tax treaties. Our aim is to turn this knowledge into value for the benefit of our clients. Tax Legal Compliance Services +Services = 5 | Tax and Legal Services Tax Services Tax is a cost of doing business and a key part of the business environment. Companies need to adapt to the tax environment in which they operate, ensuring that they meet the requirements of the environment, and that they mitigate unnecessary costs and maximize planning opportunities. Slovak tax legislation and practice is in a state of continuous change and development. The changes are influenced by a variety of factors, including the desire to adapt to the current market environment, as well as to close tax loopholes and bring Slovak tax laws into line with more developed economies. -

Choosing a Tax Advisor There Are Two Main Characteristics You Look for In

Choosing a Tax Advisor There are two main characteristics you look for in a tax professional. I call them the two “Cs”: 1. Competence and 2. Communication. The accountant/client relationship is a symbiotic association, where the accountant has the knowledge, and is able to communicate the information that the client needs to take full advantage of that knowledge. There are three designations for tax professionals (other than attorney’s) that might affect your choice. The first is the C.P.A. (Certified Public Accountant). The CPA is an individual who has successfully completed the Uniform CPA Examination. This exam is a computer based exam given at various testing centers around the country, and consists of four sections: Auditing and Attestation, Regulation, Business Environment and Concepts, Financial Accounting and Reporting. The exam is not principally concerned with taxation; therefore the CPA designation, while important, does not necessarily guarantee competence in tax matters. The CPA is required to meet stringent standards of state licensing, ethics and educational requirements, and this should give the client some comfort that the CPA is honest and professional. The second designation is that of the E.A. (Enrolled Agent), and is bestowed directly by the Internal Revenue Service. They explain it this way: An enrolled agent is a person who has earned the privilege of practicing, that is, representing taxpayers, before the Internal Revenue Service. Enrolled agents, like attorneys and certified public accountants (CPAs), are generally unrestricted as to which taxpayers they can represent, what types of tax matters they can handle, and which IRS offices they can practice before. -

Cignex Datamatics Gmbh 18-19

CIGNEX Datamatics GmbH Darmstadt Annual Financial Statements as at 31 March 2019 wts TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Acceptance of the engagement 2 2. Attestation report 3 3. Enclosures 4 Balance Sheet as at 31 March 2019 5 Income Statement from 01 April 2018 to 31 March 2019 6 Balance Sheet accounts as at 31 March 2019 7 Income Statement accounts from 01 April 2018 to 31 March 2019 9 Notes as at 31 March 2019 11 General terms and conditions 14 -1 - 1. Acceptance of the engagement The management of CIGNEX Datamatics GmbH, Darmstadt - hereinafter also "company" - engaged us to prepare the annual financial statements as at 31 March 2019 on the basis of the ac¬ counting records that we prepared, as well as the additional vouchers and inventory records provided to us, which we have not audited in accordance with the terms of our engagement, taking into account the information provided to us in accordance with the statutory requirements and in accordance with the instructions by the client within this framework to exercise existing accounting options. We performed this engagement to prepare the annual financial statements with no assessments in April 2019 in our office in Munich. General Engagement Terms General terms and conditions for German tax advisors attached these financial statements, are decisive for the realization of the engagement and our responsibility, including those to third parties. Representation letter The company provided us in writing, as requested, with the standard professional representation let¬ ter in respect of the accounting records, vouchers and inventory records as well as the information provided to us, which we have stored in our files. -

Graham Glenday, Ph.D

Graham Glenday, Ph.D. Professor of the Practice in Public Policy Studies Duke Center for International Development (DCID) Sanford School of Public Policy, Duke University Durham, North Carolina, U.S. E-mail: [email protected] KEY QUALIFICATIONS Graham Glenday is a Professor of the Practice in Public Policy Studies in the Duke Center for International Development (DCID). He is also Co-Director of the International Taxation Program, PARM, and BUDGET Programs. He came to Duke in July 2001 from Harvard University where he was Director of the Public Finance Group in the Kennedy School of Government and earlier in the Harvard Institute for International Development. He has over 20 years of international professional experience in public finance, acting as an advisor in tax policy and administration reforms and other fiscal matters to some two dozen countries in Africa, Asia and elsewhere including co-ordination of the successful Tax Modernization Program in Kenya. Earlier he served as Assistant Director of Tax Policy Analysis in the Department of Finance in the Government of Canada. Dr. Glenday has also published research and taught graduate courses and executive workshops in taxation and project appraisal matters, including the Program in Investment Appraisal and Management from 1985 onwards. Graham was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University and has a Ph.D in Public Policy from Harvard University. EDUCATION 1983 Ph.D. in Public Policy, Harvard University Dissertation entitled: “Taxation Labor Adjustment and Trade, Liberalization: Costs and Policies in the Canadian Context,” Harvard University, December 1982; advisor: Glenn P. Jenkins 1976 M.P.P., Harvard University 1974 M.A., Oxford University 1971 B.Sc., Chemical Engineering, University of Cape Town WORK EXPERIENCE DUKE UNIVERSITY July 1, 2001 – present Professor of the Practice of Public Policy Studies, Sanford School of Public Policy: Professor of the Practice in Public Policy Studies; Co-Director of International Taxation Program; and member of Public Finance Group, Duke Center for International Development 1. -

Financial Advisor Career Path Client Service Skills, Duties and Requirements

Financial advisor career path client service skills, duties and requirements Staff Financial Staff Financial Staff Financial Associate Advisor / Paraplanner Advisor 1 Advisor 2 Advisor 3 Advisor Senior Advisor Education Bachelor’s Degree (preferably in Financial Planning, Business, Accounting, Finance or related field) No experience At least 1 year 3+ years experience in the Financial Services 4+ years Minimum 5 years required experience in the industry OR 1–2 years in the experience in the experience in the Experience (prefer internship Financial Services Financial Planning field delivering Financial Planning Financial Planning experience) industry advice and services to clients field delivering field delivering advice and advice and services to clients services to clients Currently enrolled in CFP program CFP License Not Required ® CFP licensee ® or licensee ® Strong computer skills, experienced and + experienced and proficient in Portfolio center, Junxure (contact management software), Computer skills proficient in Excel and Word, basic and routine operation of Portfolio Center, and Worldox (indexing of scanned documents) Junxure and Worldox Financial Basic understanding + proficient + advanced of Naviplan (or other describing client knowledge and Planning Proficient with data entry and reviewing Not Required Financial Planning report package and expertise, ability and understanding client report package Projections software) and data Monte Carlo analysis to deliver advice (Naviplan) entry process to client to client Financial Planning Review + proficient + advanced with analyzing, knowledge and + ability to understand and summarize of client financial Update IRA and Review and understanding and expertise, ability most information from client documents; Asset/Liability summarize basic summarizing client to deliver financial documents develop agenda summary; begin information from documents, and planning advice (estate, agenda client documents retirement plans, describing to client to client insurance, etc.) SUMMIT FINANCIAL STRATEGIES 7965 N.