Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizenship, Self-Determination and Political Action: the Forging of a Political Movement

Citizenship, self-determination and political action: the forging of a political movement Jenny Morris (Talk at Conference in Sydney, Australia on Citizenship and Disability: February 1998) I want to talk about all the three things mentioned in the title of this Conference - citizenship, self-determination and political action. In order to talk about citizenship, I have to explain why I use the term 'disabled people' rather than 'people with disabilities'. The British disabled people's movement has campaigned for people to adopt a social model, rather than a medical model, of disability. The social model of disability says that: • the quality of our lives, our life chances, are not inevitably determined by what our bodies can't do or look like or how our minds function. Like the women's movement, we say - biology is not destiny. If I could not get a job that would be because of discrimination, not because I can't walk or because I'm a woman • we therefore need to separate out 'impairment' - the characteristics of our bodies and minds - from the way other people and society generally react to impairment • prejudice, discrimination, services which disempower and segregate us, a failure to use resources to create accessible environments and technology to aid communication - these are the disabling barriers that we experience • people with physical, sensory, intellectual impairments, people with mental health difficulties are therefore disabled by the society in 1 which we live • and we use the term 'disabled people' to describe what is done to us This language politicises our experiences and it takes the focus away from our impairments being the problem and puts the responsibility onto the society in which we live This is why we don't use the term disability to mean impairment. -

Nothing About Us Without Us Exhibition Large Print Text 18Pt

Nothing About Us Without Us Exhibition Large Print Text 18pt 1 Contents Introduction…………………………………………….4 Timeline………………………………………………...5 Banners……………………………………………….22 Photographs and Posters………………………......24 Placards by Jo Ann Taylor.........…………………...27 T-shirt and Other Campaign Materials Case……...28 Leaflets, Badges and Campaign Materials Case…29 Cased T-Shirts………………………………………. 35 Protest Placards…………………………………….. 36 The Autistic Rights Movement…………………….. 37 No Excuses…………………………………………. 46 Pure Art Studio……………………………………… 48 One Voice…………………………………………… 50 Quiet Riot……………………………………………. 51 Music………………………………………………… 66 2 Nothing About Us Without Us Playlist……………. 67 Interviews……………………………………………. 68 3 Introduction panel This exhibition is the second stage in a long-term project that looks at the representation of disabled people. The museum is working with groups, campaigners and individuals to capture their stories and re-examine how the history of disabled people’s activism is presented. We encourage you to let us know if you have any comments, objects or stories you would like to share to help to continue to tell this story. If you are interested in sharing your object or story as part of this project, please speak to a member of staff or contact [email protected] 4 Timeline The timeline on the wall is split into five sections: Early Days, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s and 2010s. Each section has an introductory label followed by photographs and labels with further information. Beneath the timeline is a shelf with pencils and pieces of card on it that visitors can use to write their own additions to the timeline and leave them on the shelf for other visitors to see. The introduction to the timeline is as follows: Is anything missing? Add to the timeline using the cards and shelf. -

JAN 2019 NY.Indd

VOLUME 24 NUMBER 7 JANUARY 2019 ININ THISTHIS ISSUEISSUE ADAPT IS 40 ABLE Accounts DiNapoli Urges Advocacy Org. Celebrates 4 Decades Age Expansion PAGE 2 Feds May Limit PWD Proposal Could Make Immigration Harder PAGE 3 Court Refuses Lawsuit Against Lyft Still On-going PAGE 3 N.Y. Health Act City Council Listens to Testimony PAGE 6 Financial Aid Resources Available To Students With Disabilities PAGE 8 ADAPT members hear speakers at one of several Sports events throughout the day at the organization’s Race, WC Basketball, recent 40th anniversary celebration in Denver, Skiing, Golf & Paralympics Colo. PAGES 12 & 17 Chapter members from across the country also attended a rally at Civic Center Park in Colorado, where they listened to speeches from several orig- inal ADAPT founders, members, Colorado Lt. Gov.- a bus through the night to demand accessible pub- Elect Dianne Primavera (D) and State Sen. Jessie lic transportation in Denver, Colo. Since then, the Danielson (D-Dist. 20). advocacy group has continued to grow throughout Afterwards, a memorial dinner was held honor- the country, with members organizing demonstra- ing Babs Johnson, a beloved ADAPT leader who tions, sit ins, rallies and civil disobedience, incud- died this year which was followed by a screening ing occupying senators offices in Washington, D.C. of “Piss on Pity: The Story of ADAPT” a new film on In inset photo, ADAPT organizers enjoy the ral- VISIT the history of the organization. ly. Seen left to right, are Robbie Roppolo and Dawn ABLE’S ADAPT began four decades ago when 19 activists Russell of Colorado; Mike Oxford of Kansas and WEBSITE with disabilities, known as the Gang of 19, blocked Stephanie Thomas of Texas. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Disability Drive Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0bb4c3bv Author Mollow, Anna Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Disability Drive by Anna Mollow A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kent Puckett, Chair Professor Celeste G. Langan Professor Melinda Y. Chen Spring 2015 The Disability Drive © Anna Mollow, 2015. 1 Abstract The Disability Drive by Anna Mollow Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California Berkeley Professor Kent Puckett, Chair This dissertation argues that the psychic force that Freud named “the death drive” would more precisely be termed “the disability drive.” Freud‟s concept of the death drive emerged from his efforts to account for feelings, desires, and actions that seemed not to accord with rational self- interest or the desire for pleasure. Positing that human subjectivity was intrinsically divided against itself, Freud suggested that the ego‟s instincts for pleasure and survival were undermined by a competing component of mental life, which he called the death drive. But the death drive does not primarily refer to biological death, and the term has consequently provoked confusion. By distancing Freud‟s theory from physical death and highlighting its imbrication with disability, I revise this important psychoanalytic concept and reveal its utility to disability studies. While Freud envisaged a human subject that is drawn, despite itself, toward something like death, I propose that this “something” can productively be understood as disability. -

First Impressions This Issue Begins with Some First Impressions from Two of Our New Roxburgh Scholars

ColumnTHE ISSUE 9 2009 First Impressions This issue begins with some first impressions from two of our new Roxburgh Scholars. The Roxburgh Scholarship is awarded for all-round ability and leadership potential. Heloise joined Stowe in the 3rd Form from Ashdown House in Sussex and has been enjoying a busy first term in this issue: in Queen’s House. George moved from Magdalen College School in Brackley into the Lower 6th where he is • School News P2-7 enjoying the full range of facilities Stowe has to offer. Old Stoics P8-9 “I came to Stowe from The ‘jump’ between GCSEs and A-levels is vast, but I have • a small prep school felt well accommodated in this development. The teachers • Old Stoics News P10-13 in Sussex called are supportive in and out of lessons, and the email system is Ashdown House very helpful in acquiring extra help and organising your time with a Roxburgh with staff! • School Sport P14-15 Scholarship and a There is always an opportunity to discuss concerns with Music Exhibition. individual subject teachers, which is very helpful when trying End Piece P16 At my prep school to balance academic work, sport and music. For me, this • I was Head Girl and ability to balance studies, with the things I love – sport, music captain of athletics and competitions like the Coldstream Cup – was one of the in my last year. main reasons I wanted to join Stowe. There are so many great During the first few experiences to get involved in and with some careful weeks of term we were planning, clear focus and good guidance my first half-term kept really busy. -

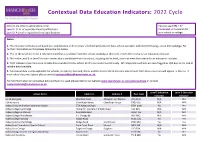

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

Wycombiensian

THE WYCOMBIENSIAN Vol. XIII No. 5 MAY, 1962 HUNT & NASH George H. Hunt. F.R.I.C.S. F.A.I. F. A. J. Nash, F.R.I.C.S., F.A.I. W. M. Creak, A.R.I.C.S. Chartered Surveyors, Valuers, Auctioneers and ESTATE AGENTS 15 Crendon Street High Wycombe Telephone: High Wycombe 884 (2 lines) and at 7 Mackenzie Street, Slough Tel.: 23295 & 6 VALUATIONS, SURVEYS TOWN PLANNING SPECIALISTS RATING AND COMPENSATION SURVEYORS Inventories, etc., Insurances effected R ents C ollected and E states M anaged DISTRICT OFFICE FOR WOOLWICH EQUITABLE BUILDING SOCIETY THE WYCOMBIENSIAN Vol. XIII No. 5 MAY, 1962 Printed by Freer & Hayter,3 Easton Street. High Wycombe BUCKINGHAMSHIRE’S DEPARTMENT STORE Tel : HIGH WYCOMBE 2424 MEET YOUR FRIENDS AT MURRAYS If you aim to start out on a career (not just ► PROSPECTS ARE EXCELLENT to take a job); if you like meeting people Promotion is based solely on merit (and, (all sorts of people); if you are interested moreover, on merit regularly, impartially in what goes on around you (and in the and widely assessed). Training is provided larger world outside) then there is much at every stage to prepare all who respond that will satisfy you in our service. to it for early responsibility and the For we provide an amazing variety of Bank's special scheme for Study Leave banking facilities through an organiza will be available to assist you in your tion of over 2,340 branches—large and studies for the Institute of Bankers small —in the cities, towns and villages of Examinations. -

Disabled People and Communication Systems in the Twenty First Century

Disabled People and Communication Systems in the Twenty First Century Alison Sheldon Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD The University of Leeds Department of Sociology and Social Policy June 2001 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge the financial support of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and British Telecom (BT). This thesis would not have been possible without the advice and support of countless others. Most importantly, I must thank all those people who participated in the fieldwork. Without your input there would have been no thesis. Thank you for giving up so much of your time, and for welcoming me into your lives. Special thanks must go to my supervisors Colin Barnes and Geof Mercer at Leeds University, and to Di Holm at BT. Thanks to Colin and Geof for giving me the opportunity in the first place, and for providing inspiration, support and friendship. Thanks to Di for her kindness, generosity and support. Thanks to my examiners, Malcolm Harrison and Michael Oliver for their helpful comments. Thanks to everyone at the Centre for Disability Research, and all those who have passed through during my time there. I have been truly fortunate to be part of such a vibrant, committed and supportive centre. Special mention must go to Hannah Morgan for her invaluable eleventh-hour assistance, and to Mark Priestley, without whom I would never have embarked on such a radical career change. -

The Wycombiensian, May 1970

G. H. HUNT, F.R.i.c.s., F.a .i. F. A. ]. NASH, f .r . i .c .s ., f .a . i . W. M. CREAK, f .r .i .c .s . Chartered Surveyors * Valuers * Auctioneers and ESTATE AGENTS Particulars of Properties in South Bucks and Herts 15 CRENDON STREET, HIGH WYCOMBE Telephone 24884 7 MACKENZIE STREET, SLOUGH Telephone 23295 81 M A RKET S T R E E T , W ATFORD Telephone 21222 D istrict Agents fo r THE WOOLWICH EQUITABLE BUILDING SO CIETY (Advances, Investments, Repayments) VALUATIONS, SURVEYS, TOWN PLANNING SCHEMES AND APPEALS COMPULSORY PURCHASE ORDERS RENTS COLLECTED AND ESTATES MANAGED INVENTORIES AND INSURANCES THE WYCOMBIENSIAN Vol. XV No. 9 MAY, 1970 Hull Loosley & Pearce Complete School Outfitters BLAZERS IN BARATHEA TROUSERS IN TERYLENE/WORSTED SCHOOL TIES IN TERYLENE PREFECTS' TIES AND COLOURS TIES IN TERYLENE RAINCOATS BY ROBERT HIRST SPORTS KITS BY BUKTA 6th FORM BLAZERS, BADGES AND SCARVES OLD BOYS' BLAZERS, BADGES AND TIES 29-30-31 OXFORD STREET HIGH WYCOMBE PHONE 33222 THE WYCOMBE BOOKSHOP LTD 63 CASTLE STREET HIGH WYCOMBE, BUCKS FOR BOOKS OF ALL DESCRIPTIONS Telephone : High Wycombe 28021 S. C. WILLOTT Fine Quality STUDENTS’ CASES - SATCHELS ATTACHE CASES - BRIEF CASES HANDBAGS - SUIT CASES SMALL LEATHER GOODS - TRUNKS UMBRELLAS 17/19 Crendon St., High Wycombe Telephone : 27439 For Your MEN’S and BOYS’ WEAR . G. A. WOOD . EVERY TIME ★ FOR THE BEST VALUE AT A REASONABLE PRICE ★ THE COMPLETE OUTFIT FOR YOUR SCHOOL MODERN STYLE CLOTHES FOR THE YOUNG MAN and M E N ’S W E A R For Work or Leisure FOR SELECTION — FOR STYLE — FOR VALUE — FOR PERSONAL SERVICE . -

Disability, Rights and Vulnerability in British Parliamentary Debate

DRAFT Disability, Rights and Vulnerability in British Parliamentary Debate Evan Odella aDisability Rights UK 14 East Bay Lane, Plexal, London E15 2GW ARTICLE HISTORY Compiled July 10, 2018 ABSTRACT This paper examines discussion of disability and disabled people by Members of Parlia- ment (MPs) in the UK House of Commons from 1979–2017. It examines general trends in the number of speeches mentioning disability, including the parties and MPs most likely to mention disability issues, and examines how disability is used in conjunction with two keywords: ‘rights’ and ‘vulnerable’. It uses these keywords to explore two conceptions of how the state should engage with disability and disabled people: a paternalistic concep- tion (which post-2010 has become more common) and a rights-based conception (which has been in decline since the 1990s). I conclude with a discussion about how this reflects the disability movement in the UK, and what it means for the future of disability politics, the welfare state and how disabled people themselves might view paternalistic government policies. Abbreviations: SNP: Scottish National Party DPAC: Disabled People Against the Cuts MP: Member of Parliament KWIC: Key Words in Context KEYWORDS Disability, Politics, Hansard, Political Discourse 1. Introduction The way politicians approach, discuss and debate an issue can reveal how that given issue is viewed, and the predict the policy responses to that issue. The tone of political rhetoric both informs and reflects popular conceptions, media coverage and public policies on a given issue or set of issues. Discourse, amongst politicians, mass media and the general public, has been a long-standing concern in the field of disability studies, particularly fo- cusing on popular descriptions of disability and how these can harm (or help) disabled people, or the language and arguments used by governments to ‘sell’ different policies. -

2019-Conference-Guide.Pdf

A Message from the Executive Director Dear Advocates and Friends, NCIL’s 2019 Annual Conference theme is IGNITE. The Independent Living Movement ignites action and empowerment. When there is work to be done, we do it. When bad policy threatens our independence and rights, we fight back. When we know we have a better way, we take action to influence policy and pass laws. We are organized, we are powerful, and we know what we want. We must share resources, strategize, and train new advocates if we want to succeed in our efforts to protect our programs and NOTES secure the independence of people with disabilities. Questions: Contact us at NCIL’s Annual Conference is the largest Independent Living event [email protected] of the year. NCIL regularly hosts over 1,000 people, including grassroots advocates, CIL and SILC leadership, members of Registration Congress, government officials, and representatives from other major organizations that work for justice and equity for people with You may register multiple disabilities. people in one transaction by using our online store. Visit Please join us in Washington this July to show our power, take to ncil.org for: the streets, and share our message. Together, our individual sparks will ignite a flame that cannot be ignored. online registration printable registration Your Partner in Disability Rights, forms personal assistant registration Contact [email protected] for Kelly Buckland sponsor registration. Executive Director Participants must register for the Conference before being eligible for a discounted rate Table of Contents at the hotels. A Message from the Executive Director: 2 See Pages 17-19 for complete registration details. -

Introduction: Global Disability Studies

ONE Introduction: Global Disability Studies ******************************************************* Introduction Disability studies understand their subject matter as social, cultural and political phenomena. In defining terms, describing positions and laying foundations, we will interrogate the literature in ways that encourage us to think about where we sit/stand in relation to pan-national and cross-disciplinary perspectives on disability that have the potential to support the self-empowerment of disabled people. This first chapter sets the theoretical tone. The global nature of disability The word ‘disability’ hints at something missing either fiscally, physically, mentally or legally (Davis, 1995: xiii). To be disabled evokes a marginalised place in society, culture, economics and politics. It is concentrated in some parts of the globe more than others, caused by armed conflict and violence, malnutrition, rising populations, child labour and poverty. Paradoxically, it is increasingly found to be everywhere, due to the expo- nential rise in the number of psychiatric, administrative and educational labels over the last few decades. Disability affects us all, transcending class, nation and wealth. The notion of the TAB – Temporarily Able Bodied – recognises that many people will at some point become disabled (Marks, 1999a: 18). Most impairments are acquired (97%) rather than congenital (born with) and world estimates suggest a figure of around 500–650 million disabled people, or one in ten of the population (Disabled-World. com, 2009), with this expected to rise to around 800 million by the year 2015 (Peters et al., 2008). Currently, 150 million of these are children (Grech, 2008) and it is esti- mated that 386 million of the world’s working-age population are disabled (Disabled- World.com, 2009).