Victor's Field – the Story of Chapman Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Altis Ludlam-Miami, LLC (CDMP20180006) Commission District 7 Community Council 12

Altis Ludlam-Miami, LLC (CDMP20180006) Commission District 7 Community Council 12 APPLICATION SUMMARY Applicant/Representative: Altis Ludlam–Miami, LLC/Juan J. Mayol, Jr., Esq., & Gloria M. Velazquez, Esq., & Hugo P. Arza, Esq., Holland and Knight, LLP Location: Southeast corner of SW 40 Street and SW 70 Court Total Acreage: ±3.48 gross acres/ ±2.73 net acres Current Land Use Plan Map Designation: “Business and Office” and “Industrial and Office” Requested Land Use Plan Map “Special District – Ludlam Trail Corridor District” Designation and other changes: Amendment Type: Small-scale Existing Zoning District/Site Condition: BU-2, BU-3, and IU-1 / Vacant RECOMMENDATIONS Staff: ADOPT AS A SMALL-SCALE AMENDMENT WITH ACCEPTANCE OF THE PROFFERED DECLARATION OF RESTRICTIONS (August 2018) Kendall Community Council (12): ADOPT, WITH THE CONDITION THAT THE HEIGHT OF STRUCTURES FRONTING SW 40 STREET (BIRD ROAD) BE LIMITED TO 6 STORIES AND TRANSITION TO NO MORE THAN 4 STORIES ON THE SOUTHERNMOST PORTION OF THE PROPERTY (September 4, 2018) Planning Advisory Board Acting as TO BE DETERMINED (September 24, 2018) the Local Planning Agency: Board of County Commissioners: TO BE DETERMINED (September 27, 2018) Expedited Application 1 Application No. CDMP20180006 Revised and Replaced September 4, 2018 Staff recommends to ADOPT AS A SMALL-SCALE AMENDMENT the proposed change to the Comprehensive Development Master Plan (CDMP) Adopted 2020 and 2030 Land Use Plan (LUP) map to redesignate the ±3.48-gross acre site from “Business and Office” and “Industrial and Office” to the “Special District – Ludlam Trail Corridor District” for the following reasons: Principal Reasons for Recommendation: 1. -

Five-Year Implementation Plan of the People’S Transportation Plan

Five-Year Implementation Plan of the People’s Transportation Plan Eighth Annual Update ∙ Covering Fiscal Years 2020–2025 CITIZENS’ INDEPENDENT TRANSPORTATION MOVINGMOVINGMOVING TRUST FORWARDFORWARDFORWARD PTP Five-Year Plan Update Five-Year Implementation Plan of the People’s Transportation Plan (PTP) Eighth Annual Update – Covering Fiscal Years 2020 to 2025 Citizens’ Independent Transportation Trust and Miami-Dade County Chairman’s Message As I embark on my new role as the Chairman of the Citizens’ Independent Transportation Trust (Transportation Trust), I’m reminded that Miami-Dade County is a great place to live, work and play. Public Transportation plays a vital role in both the economic and physical health of our residents and offers great benefits to the community. The Transportation Trust is dedicated to its core responsibilities-- to provide oversight of the People’s Transportation Plan (PTP) funds and develop proactive plans that meet the challenges of improving public transportation in our community. My fellow Trust Members and I remain committed in safeguarding the public’s money and we work diligently to maintain their confidence ensuring that the half-penny transportation Surtax funds are spent as intended. We are excited about the accomplishments made with the half-penny Surtax thus far and look forward to continuing to fulfill our remaining promises by implementing the Strategic Miami Area Rapid Transit (SMART) Plan. Miami-Dade County desires to provide a public transportation system that keeps pace with the needs of this growing population and their transportation needs. I serve on the Transportation Trust because I believe in the potential of this community and residents of Miami-Dade County deserve a first-class transportation system. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

US 1 from Kendall to I-95: Final Summary Report

STATE ROAD (SR) 5/US 1/DIXIE HIGHWAY FROM SR 94/SW 88 STREET/ KENDALL DRIVE TO SR 9/I-95 MIAMI-DADE COUNTY, FLORIDA FDOT FINANCIAL PROJECT ID: 434845-1-22-01 WWW.FDOTMIAMIDADE.COM/US1SOUTH March 2019 Final Summary Report ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to the many professionals and stakeholders who participated in and contributed to this study. From the communities along the corridor to the members of the Project Advisory Team, everyone played a crucial role in forming the results and conclusions contained in this study. 2 STATE ROAD (SR) 5/US 1/DIXIE HIGHWAY FROM SR 94/SW 88 STREET/KENDALL DRIVE TO SR 9/I-95 This report compiles the results of the State Road (SR) 5/US 1/ Dixie Highway from SR 94/SW 88 Street/Kendall Drive to SR 9/I-95 Corridor Study and includes: › Findings from the study › Recommendations for walking, bicycling, driving, and transit access needs along US 1 between Kendall Drive and I-95 › Next steps for implementing the recommendations This effort is the product of collaboration between the Florida Department of Transportation District Six and its regional and local partners. FDOT and its partners engaged the community at two critical stages of the study – during the identification of issues and during the development of recommendations. The community input helped inform the recommended strategies but the collaboration cannot stop here. Going from planning to implementation will take additional coordination and, in some instances, additional analysis. FDOT is able and ready to lead the effort but will continue seeking the support of community leaders, transportation and planning organizations, and the general public! To learn more, please read on and visit: www.fdotmiamidade.com/us1south WWW.FDOTMIAMIDADE.COM/US1SOUTH 3 CONTENTS 1. -

America's Last Hope?

Wars on Christians Not Hitler’s Pope Empire or Umpire? Food Rights Fight ANDREW DORAN JOHN RODDEN & JOHN ROSSI ANDREW J. BACEVICH MARK NUGENT JULY/AUGUST 2013 ì ì#ììeìì ì ì # America’s Last Hope? ììeì ì ìeì ì ìì #ì ìeì ìì ! $9.99 US/Canada theamericanconservative.com Visit alphapub.com for FREE eBooks and Natural-law Essays We read that researchers have used new technology to fi nd proof behind biblical stories such as the Parting of the Red Sea and the Burning Bush. Our writing uses a biblical story with a deadly result that is still happening today. This biblical event is the creator’s command to Adam: “Of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat or you “Just found your site. will surely die.” Adam and Eve did eat the fruit of that tree, and for I was quite impressed disobeying the creator, they suffered much trouble and fi nally died. and look forward to Experience tells us that people worldwide are still acting on hours of enjoyment their judgments of good and evil. Now, consider what happens to and learning. Thanks.” millions of them every day? They die! It would follow that those - Frank whose behavior is based on their defi nitions of good and evil be- come subject to the creator’s warning, “or you will surely die.” We know that when people conform to creation’s laws of physics, right action always results. Children learn to walk and run by con- forming to all applicable natural laws. -

Restoring Southern Florida's Native Plant Heritage

A publication of The Institute for Regional Conservation’s Restoring South Florida’s Native Plant Heritage program Copyright 2002 The Institute for Regional Conservation ISBN Number 0-9704997-0-5 Published by The Institute for Regional Conservation 22601 S.W. 152 Avenue Miami, Florida 33170 www.regionalconservation.org [email protected] Printed by River City Publishing a division of Titan Business Services 6277 Powers Avenue Jacksonville, Florida 32217 Cover photos by George D. Gann: Top: mahogany mistletoe (Phoradendron rubrum), a tropical species that grows only on Key Largo, and one of South Florida’s rarest species. Mahogany poachers and habitat loss in the 1970s brought this species to near extinction in South Florida. Bottom: fuzzywuzzy airplant (Tillandsia pruinosa), a tropical epiphyte that grows in several conservation areas in and around the Big Cypress Swamp. This and other rare epiphytes are threatened by poaching, hydrological change, and exotic pest plant invasions. Funding for Rare Plants of South Florida was provided by The Elizabeth Ordway Dunn Foundation, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and the Steve Arrowsmith Fund. Major funding for the Floristic Inventory of South Florida, the research program upon which this manual is based, was provided by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and the Steve Arrowsmith Fund. Nemastylis floridana Small Celestial Lily South Florida Status: Critically imperiled. One occurrence in five conservation areas (Dupuis Reserve, J.W. Corbett Wildlife Management Area, Loxahatchee Slough Natural Area, Royal Palm Beach Pines Natural Area, & Pal-Mar). Taxonomy: Monocotyledon; Iridaceae. Habit: Perennial terrestrial herb. Distribution: Endemic to Florida. Wunderlin (1998) reports it as occasional in Florida from Flagler County south to Broward County. -

If It's Summer, It Must Be Alexander Camp!

IF IT’S SUMMER, IT MUST BE ALEXANDER CAMP! 2020 PRE-CAMP FUN WEEK JUNE 8-12 SUMMER PROGRAMS JUNE 15-AUGUST 7 POST-CAMP FUN WEEK AUGUST 10-14 THERE’S NO CAMP QUITE LIKE ALEXANDER CAMP! IT’S ALL ABOUT FUN. IT’S ALL ABOUT FRIENDSHIP. Alexander Camp is also about fostering a sense enjoyment and engagement in your child. Through a variety of stimulating activities, your child is provided with the opportunity to discover teamwork and sportsmanship, a love of learning, and renewed self-confidence - all while having a blast! THERE’S SOMETHING FOR EVERYONE! ABOUT ALEXANDER Talk about kid-friendly . Designed for children from 3-12 years of age, Alexander Camp is conveniently MONTESSORI SCHOOL located, affordable, and offers a variety of different Founded in 1963, family-owned programs geared to your child’s age, stamina, and skill Alexander Montessori has taught level. Our campers also come from all over the world, children to love to learn for over so no two students are alike in personality, talent, or world half a century. We’ve earned a view. To meet the needs of every student, we alternate superior reputation as one of the the indoor and outdoor events, varying them in length nation’s leading “authentic” according to the activity and the age/interest of each group. Montessori schools, one And the environment is always supportive, respectful, and outstanding student at a time. designed to bring out the best in each child. JUST A SAMPLING OF ACTIVITIES INCLUDES: EXERCISE Team Sports Dance/Aerobics Tennis Daily Swimming RECREATION Archery Video Games Electric Go-Karts Jumbo Games Playground CREATIVITY ELEMENTARY ALL-AROUND CAMP ELEMENTARY Arts and Crafts Rock Band Drama FUN STUFF Cool Field Trips Mad Science Moonwalk (bounce house) Mini Golf Kites Scavenger Hunts Sky Ride (a ski-chair lift-like READY, cable that goes downhill) Summertime Treats SET. -

Chapman Field–The Evolution of a South Dade Army Airdrome

58 Chapman Field-The Evolution of a South Dade Army Airdrome Raymond G. McGuire Cobbled together to encompass more than 850 acres of pineland, scrub, marsh, and seashore, the army airfield that came to be named after the first U.S. flier killed in France during World War I saw active service for only two months before the war ended. Thereafter local horticulturists and aviation interests vied for control of the property as development crept around its perimeter. With much of the acreage remaining park- land or agricultural through the end of the twentieth century, Chapman Field has persisted as an identifiable entity in Miami-Dade County with a locally recognized name long after its airstrips have vanished.1 Powered flight had barely passed its first decade when the war in Europe erupted in 1914, but German, French, and English govern- ments quickly saw the strategic advantages to be gained from the air- plane over the battlefield. During the first years of the war the United States had a chance to watch from the sidelines, and it, too, discovered that air power was a potentially great new tactic. The U. S. Army had few pilots, however, and few bases for training more; in Florida, only the Naval Air Station in Pensacola was operational. America entered the war on April 6, 1917, and, in a wave of federal spending, $640 million was appropriated by Congress on July 24 of that year for military aeronautics. Many private schools of aviation were taken over by the military, such as Curtiss Field in Miami, and new airfields were estab- lished throughout the country. -

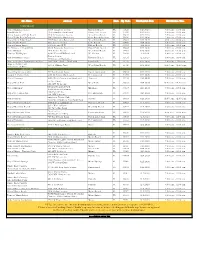

Distribution Dates 11.20.2020 PM

Site Name Address City State Zip Code Distribution Date Distribution Time PALM BEACH City of Boynton Beach 801 N Congress Avenue Boynton Beach FL 33426 11.21.2020 9:00 a.m. - 11:00 a.m. Royal Palm CF 9905 Southern Boulevard Royal Palm Beach FL 33411 11.21.2020 9:00 a.m. - 11:00 a.m. Urban League of Palm Beach 1700 N Australian Avenue West Palm Beach FL 33407 11.21.2020 9:00 a.m. - 11:00 a.m. City of Palm Beach Gardens 5343 Northlake Boulevard Palm Beach Gardens FL 33418 11.23.2020 9:00 a.m. - 11:00 a.m. City of West Palm Beach 1751 Palm Lakes Boulevard West Palm Beach FL 33401 11.23.2020 8:00 a.m. - 10:00 a.m. City of Lake Worth 1121 Lucerne Avenue Lake Worth FL 33460 11.24.2020 9:00 a.m. - 11:00 a.m. City of Riviera Beach 2409 Avenue H W Riviera Beach FL 33404 11.24.2020 9:00 a.m. - 11:00 a.m. The Villages at Royal Palm 11600 Poinciana Boulevard Royal Palm Beach FL 33441 11.25.2020 9:00 a.m. - 11:00 a.m. United Haitian 2015 Parker Avenue West Palm Beach FL 33401 11.25.2020 10:30 a.m. - 12:30 p.m. Town of Wellington 10300 Forest Hill Boulevard Wellington FL 33414 12.1.2020 8:00 a.m. - 11:00 a.m. Hester Center - City of Boynton Beach Boynton Beach FL 33435 12.3.2020 8:00 a.m. -

Local Mitigation Strategy Whole Community Hazard Mitigation

Local Mitigation Strategy Whole Community Hazard Mitigation Part 2: The Projects January 2017 The Miami-Dade Local Mitigation Strategy Part 2: The Projects This page left intentionally blank. January 2017 P2-ii The Miami-Dade Local Mitigation Strategy Part 2: The Projects TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................... 1 PROJECT SUBMITTAL AND TRACKING ................................................................................................. 1 PROJECT REQUIREMENTS .................................................................................................................. 1 UPDATES AND REPORTS .................................................................................................................... 3 PROJECT ADMINISTRATION AND IMPLEMENTATION .............................................................................. 4 LETTERS OF SUPPORT ....................................................................................................................... 4 PROJECT ARCHIVING ......................................................................................................................... 4 PROJECT DELETION ........................................................................................................................... 4 INACTIVE PROJECTS ......................................................................................................................... -

Miami-Dade Transportation Planning Organization Study Aims to Tie Bike, Walking Trails Into Mass Transit Plan

Miami-Dade Transportation Planning Organization study aims to tie bike, walking trails into mass transit plan Written by Jesse Scheckner on July 2, 2018 The Miami-Dade Transportation Planning Organization has ordered a budget to study a project to connect non-motorized bicycle and pedestrian paths with the Strategic Miami Area Rapid Transit (SMART) Plan. “We’re going to get all the trails united,” Commissioner Rebeca Sosa said after voting for the plan and asking to co-sponsor the resolution by City of Miami Mayor Francis Suarez. Several major public-private trail projects could be considered for a SMART Trails program, including the Underline, a 10-mile linear park and urban trail below the Metrorail running from the Miami River north of the Brickell Metrorail station to the Dadeland Metrorail station; the 6.2- mile multi-use Ludlam Trail running parallel to and west of Ludlam Road from near Northwest Seventh to Southwest 80th streets; and the Miami River Greenway, a public pathway running about 5.5 miles on both sides of the river west from Biscayne Bay toward Miami International Airport. Around 20 community members arrived to support the SMART Trails program, including Citizens’ Independent Transportation Trust Executive Director Javier Betancourt, Everglades Bicycle Club President Susan Kawalerski, Friends of the Underline founder Meg Daly and Swire Properties Development Manager of Community Outreach Jami Reyes. “As a daily bike commuter, my bike is like the horizontal elevator that takes me from my house to our transit system,” said town planner Victor Dover, who in November 2015 helped bring WHEELS, a four-day biking, walking and transit educational event, to South Miami. -

APPENDIX J: 2020‐21 CAPITAL BUDGET (Dollars in Thousands)

APPENDIX J: 2020‐21 CAPITAL BUDGET (dollars in thousands) ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐2020‐21‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Projected Strategic Area / Department Prior Years Bonds State Federal Gas Tax Other 20‐21 Total Future Total Cost Public Safety Corrections and Rehabilitation COMMUNICATIONS INFRASTRUCTURE EXPANSION 709 300 00010 300 291 ,300 INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENTS ‐ METRO WEST DETENTION CENTER ‐ 346 354 000 0 354 0 700 AIR HANDLERS INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENTS ‐ METRO WEST DETENTION CENTER ‐ 0 750 00010 750 750 ,500 ELEVATOR REFURBISHMENT INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENTS ‐ METRO WEST DETENTION CENTER ‐ 50 200 000 0 200 0 250 EXTERIOR MECHANICAL ROOM DOORS INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENTS ‐ METRO WEST DETENTION CENTER ‐ 1,750 800 00020 800 0 ,550 FACILITY ROOF REPLACEMENTS INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENTS ‐ METRO WEST DETENTION CENTER ‐ 924 76 00010760,000 GENERATORS INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENTS ‐ METRO WEST DETENTION CENTER ‐ 3,673 200 00040 200 382 ,255 INMATE HOUSING IMPROVEMENT INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENTS ‐ PRE‐TRIAL DETENTION CENTER ‐ 17,693 200 000 0 200 129 18,022 RENOVATION INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENTS ‐ TURNER GUILFORD KNIGHT 425 275 000 0 275 0 700 CORRECTIONAL FACILITY ‐ AIR HANDLERS INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENTS ‐ TURNER GUILFORD KNIGHT 3,751 200 00040 200 349 ,300 CORRECTIONAL FACILITY ‐ FACILITY ROOF REPLACEMENTS INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENTS ‐ TURNER GUILFORD KNIGHT 120 200 000 0 200 180 500 CORRECTIONAL FACILITY ‐ RECREATION YARD STORE FRONTS INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENTS ‐ CORRECTIONAL FACILITIES 0 556 000 0 556 78,331 78,887 SYSTEMWIDE TURNER