St Peter's Church Bywell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Sale – Residential Development Opportunity

For Sale – Residential Development Opportunity Shaw House Farm, Newton, Stocksfield, Northumberland, NE43 7UE • Residential Development Opportunity • Full Planning Permission Granted • Site Area: 0.5 hectares (1.24 acres) • Planning Reference: 18/03543/FUL Guide Price £950,000 • Rural Location • Freehold ALNWICK | DURHAMD U R H A| M GOSFORTH | N E W C A S | T LMORPETH E | SUNDERLAND | NEWCASTLE | LEEDS | SUNDERLAND D U R H A M | N E W C A S T L E | SUNDERLAND | LEEDS FOR SALE – Residential Development Opportunity Shaw House Farm, Newton, Stocksfield, Northumberland, NE43 7UE OPPORTUNITY Bradley Hall are delighted to offer this residential development opportunity for the conversion of traditional agricultural buildings to 7 residential units with associated access and parking with the demolition of modern agricultural buildings to the north. LOCATION & DESCRIPTION The site is located to the south of Newton, 1.5m to the north of Bywell and 1.9m to the north of Stocksfield which benefits from a train station and bus service links to Hexham. The A69 is located to the south of the farmstead providing access directly into Newcastle to the east and Corbridge/Hexham to the west. The site is located to the east of Shaw House Farmhouse and is bounded by the existing access road leading to Newton on the western boundary. To the southern boundary there is existing residential uses and to the northern and eastern boundaries is open agricultural land. The subject site, known as Shaw House Farm, comprises several agricultural buildings currently utilised for sheep farming. Buildings on site include large, modern steel portal framed barns across the northern portion of the site upon concrete pads; several connected agricultural buildings of sandstone and timber construction, located centrally; and a square shaped barn located to the south-west formed of three rectangular structures, two of sandstone and timber, and the middle of steel portal frame construction. -

Northeast England – a History of Flash Flooding

Northeast England – A history of flash flooding Introduction The main outcome of this review is a description of the extent of flooding during the major flash floods that have occurred over the period from the mid seventeenth century mainly from intense rainfall (many major storms with high totals but prolonged rainfall or thaw of melting snow have been omitted). This is presented as a flood chronicle with a summary description of each event. Sources of Information Descriptive information is contained in newspaper reports, diaries and further back in time, from Quarter Sessions bridge accounts and ecclesiastical records. The initial source for this study has been from Land of Singing Waters –Rivers and Great floods of Northumbria by the author of this chronology. This is supplemented by material from a card index set up during the research for Land of Singing Waters but which was not used in the book. The information in this book has in turn been taken from a variety of sources including newspaper accounts. A further search through newspaper records has been carried out using the British Newspaper Archive. This is a searchable archive with respect to key words where all occurrences of these words can be viewed. The search can be restricted by newspaper, by county, by region or for the whole of the UK. The search can also be restricted by decade, year and month. The full newspaper archive for northeast England has been searched year by year for occurrences of the words ‘flood’ and ‘thunder’. It was considered that occurrences of these words would identify any floods which might result from heavy rainfall. -

North East Inheritance

North East Inheritance Exhibition Catalogue 21 September – 16 October 2009 Palace Green Library 1 The North East Inheritance Project Durham University Library today holds some 150,000 probate records of 75,000 individuals from County Durham and Northumberland - the old Durham diocese - who lived between the early 16th century and the mid-19th century. With the support of the Heritage Lottery Fund, English Record Collections, Durham University and the Genealogical Society of Utah the North East Inheritance project has catalogued and digitally photographed the Durham diocese probate collection (1526- 1858). The collection will be made freely available online in 2010. Probate is the process of proving a will and of administering the estate of a deceased person. This process is today overseen nationally by the civil courts, but before 1858 probate business in England and Wales was administered in the main by ecclesiastical courts in a system of provincial, diocesan and special jurisdictions. In the natural course of several hundred years of this work substantial probate record collections have accumulated in various registries and archives. Making the Durham records available online and for free now offers to historians and genealogists an unsurpassed opportunity for study and discovery. This exhibition offers a selection of probate records from the Durham collection. These have been chosen to illustrate both the probate process and various typical document types, and also to illustrate a number of research topics for which probate records can provide important evidence. The plan of the exhibition topics is as follows. 1 Introduction p.3 2 Family History p.5 3 Local History p.9 4 Academic Use of Probate p.13 5 Death, Dying and Disposal p.17 6 Health and Medicine p.20 7 Plague p.23 8 The Wreck of the Palermo p.26 9 Trade and Industry p.28 10 Literacy and Education p.31 11 Enemies, Foreign and Domestic p.33 12 Northeasterners Abroad p.36 Will of Peter Trumbel of Gateshead, butcher. -

Tyne Crossings at Hexham up to 1795

X Tyne Crossings at Hexham up to 1795 Stafford M. Linsley INTRODUCTION explain why it was once a more important centre than Hexham. RIDGES are more or less taken for gran In June 1263, the Abbot of Holm Cultram Bted today, but at the middle of the 18th claimed free passage of carts and carriages century they were relatively rare in the rural "beyond the bridge of Hexham" as an ancient parts of north-east England; this was largely privilege, presumably implying a bridge over because no particular body was responsible for the Tyne. This bridge seems to have been building them. Subsequently many more brid destroyed subsequently for consideration was ges were built, a steady proliferation which given to the building of a bridge in 1294; in accelerated rapidly in the nineteenth century. 1307 the Archbishop was concerned about Surviving bridges are by definition the success funds for its repair and completion, and it ful ones, but this article includes a discussion of seems safe to assume that it was never built. two comprehensive bridge collapses at Hex Given such few indications of early bridges at ham in the eighteenth century. In 1986 the Hexham, it is clear that fords and ferries pro highest ever recorded flow rate for any river in vided the crossings over the Tyne for centuries the kingdom was measured on the Tyne at before a successful bridge was built. There is, Bywell, yet it is believed that in the great flood not surprisingly, very little documentation for of 1771, the flow rate at Hexham might have the fords; in Coastley, part of the West Quarter been two and a half times greater.1 Little of Hexham, the Order of the Watch in 1522, wonder, it might be thought, that some river stipulated that:4 bridges failed to withstand such an onslaught. -

XI the Great Inundation of 1771 and the Rebuilding of the North-East's

XI The Great Inundation of 1771 and the Rebuilding of the North-East’s Bridges R. W. Rennison n 1771 a major flood on the rivers of north- All but one of the bridges were of masonry – east England led to the destruction of many arched in form – and the majority of those Ibridges. As an entity, the programme of damaged or destroyed were the responsibility reconstruction has never before been recorded of the Counties’ Justices and administered and this paper has been prepared in an eVort to through Quarter Sessions; some bridges, how- rectify this omission. The majority of the bridges ever, were built under the aegis of private indi- were the property of the respective County viduals or bodies. Rebuilding work was the administrations and, in order to describe the responsibility of either the oYcers of the Coun- rebuilding, the Quarter Sessions records of the ties’ government or consultants. Brief bio- four counties aVected have been used extensively. graphical details of some of these are given in the Appendix – their names are followed by an asterisk (*) where they appear in the text. INTRODUCTION Bridge rebuilding took place at the time of the formation of a civil engineering profession – In the history of river crossings in the north the Society of Civil Engineers was founded in east of England, the major flood of 1771 – the 1771 – and it brought to the area two of its ‘Great Inundation’ – was a landmark, resulting earliest and most distinguished members, John as it did in the destruction of a score of bridges Smeaton and Robert Mylne, although they on the rivers Tyne, Wear and Tees. -

An Examination of Roman Stones Re-Uifed in an Anglo-Saxon Context

Durham E-Theses The appropriation of meaning: an examination of roman stones re-used in an Anglo-Saxon context Catling, Joanne Elizabeth How to cite: Catling, Joanne Elizabeth (1998) The appropriation of meaning: an examination of roman stones re-used in an Anglo-Saxon context, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4665/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 THE APPROPRIATION OF MEANING: an examination of Roman stones re-uifed in an Anglo-Saxon context Joanne Elizabeth Catling MJk. UNTVERSITY OF DURHAM Department of Archaeology The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be pubHshed without the written consent of the author an information derived from it should be acknowledged. 1998 2 THE APPROPRIATION OF MEANING: an examination of Roman stones re-used in an Anglo-Saxon contcj^t. -

![Bywell. [Northumberland.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2847/bywell-northumberland-5182847.webp)

Bywell. [Northumberland.]

DIRECTORY. ;3i BYWELL. [NORTHUMBERLAND.] .- . .. The population of the parish, in 18.)1, was 480; and the south-east from Corbridge. It is in the east division of acreage 3,512. 'l'he population of the township was 46. It Tindale ward, south division of the county, Hexham union, is situated on either sides of the river Tyne, and comprises COl'bridge deaner~T, ~orthumberland archdeaconry, and the townships of BEARL, BROOMHAUGH, BYWELL ST. Durham bishopric. 'l'he population, in 18.:11, was 134:, and A:SDREW, RIDING. STOCKSFIELD HALL, and STYFORD. the acreage is 800. It is situated on the southern shore of The Newcastle and Carlisle railway, and the turnpike road the river Tyne, amI on the road fi'om Hexham to New from Newcastle-on-Tyne to Hexham, run through the castle-on-Tyne. The church of St. James, a stone building parish. The church, dedicated to St. Andrew, is an ancient recently erected, is a beautiful structure, having a spire stone building, having nave and chancel, aisles, porch, tran- 60 feet high, and is capable of seating 160 people, besides septs, and tower containing 2 bells, an organ, font, and old school children; it is a chapel ofease to ByweIl St. Andrew. register. The living is a vicarage, value £159 yearly, with There is a National school for boys and girls, and also a residence, in the gift of 'Ventworth Blackett Beaumont, Baptist chapel, erected in 1842. Wentworth Blackett Beau Esq., M.P. The Rev. Joseph Jaques is the incumbent. mont, Esq., M.P., vVilliam Bacon Grey, and Jacob Wilson, 'Ventworth Blackett Beaumont, Esq., )LP., is lord of the Esqrs., executors of John Shields, Esq., are chieflandowners. -

Slaley Parish Council March 9Th 2020 Minutes

Minutes of Slaley Parish Council Monday March 9th 2020 at 7.30 p.m. in Slaley Commemoration Hall 1. Public Participation. None 2. Apologies. Councillor A.M. Livesey. County Councillor Colin Horncastle. Present: Councillor R.W.H. Hutchinson in the Chair. Councillors S. Carson, S. C. Douglas, J. Storey, D. J. Taylor & Clerk Mrs P. Wilson. 3.Declaration of Interests and Hospitality Record. None 4. Minutes of February 10th 2020 meeting (circulated pages 1426 – 1429). Appendix 1, page 1430, appendix 2, page 1431, appendix 3, page 1432 & appendix 4, page 1433. The Minutes were proposed as a true record by Cllr S. Carson and seconded by Cllr S. C. Douglas. The minutes were then signed and dated. 5.Matters Arising. a) 5a 10/2/20; 5a 13/1/20; 5b 9/12/19; 7g 11/11/19: Neighbourhood Planning – Reminder Jenny Ludman been invited to speak at Slaley PC on Monday April 6th about a NP. b) 5b 10/2/20; 5b 13/1/20; 5c 9/12/19; 14b 11/11/19: Footpath parking an email was sent to the owner of Clairemont asking if alternative arrangements for the Milburn coach could be made. Telephone call to Clerk from driver of coach asking why a complaint had been made. Clerk explained that parking opposite Slaley Community Shop during daylight hours was not acceptable. Larger vehicles stopping at the Shop and his mini van parked opposite was causing problems for other village traffic. PC Clerk suggested paying for parking in R&C or TR car park if none available at Claremont. -

{TEXTBOOK} Directory of British Tramways Volume Three : Northern England, Scotland and Isle of Man Ebook

DIRECTORY OF BRITISH TRAMWAYS VOLUME THREE : NORTHERN ENGLAND, SCOTLAND AND ISLE OF MAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Keith Turner | 224 pages | 05 Apr 2010 | The History Press Ltd | 9780752442396 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom Directory of British Tramways Volume Three : Northern England, Scotland and Isle of Man PDF Book He publicly used the arms of the Lawsons of Longhirst in Northumberland and doubtless belonged to a branch of that family. From the 12th century onwards, its history has been mostly rural, incorporating several farms and the parish church of St. He had already determined that the north had to be taught a military lesson. Finally, in , the Hundred Years War ends. He also purchased the Brayton Hall estate. Many of these families also had cross border links. Anthony by act of Parliament on death of his brother James and Henry. Iinspired by Joan of Arc's leadership and sacrifice the French continued to fight and ultimately push the English army out of France. The focal point of this rebellion was Ely Abbey which was a stone fortress that presented a formidable challenge to the attackers led by William and Ivo. An old Roman Road ran through the place extending on to Lincolnshire. For the first time since the Roman occupation , the Ministry of Transport took direct control of the core road network through the Trunk Roads Act Some historians mark this as the end of the Viking Age. Jone Lawson survived the dissolution of her house some seventeen years probably living in one of the convent buildings possibly a tenant of her brother. -

A-Z Index 1858-1878

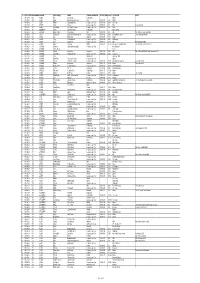

DATE PROVED PAGE NUMBER SURNAME FIRST NAME[S] ABODE TOWN/VILLAGE/PARISH DATE OF DEATH VALUE OCCUPATION NOTES 1863-09-07 308 ABBOT John Gateshead(Durham) 1863-07-18 £300,000 Iron Manufacturer 1867-02-22 90 ABBOT John George 4,Saville Place Newcastle upon Tyne 1867-02-05 £600,000 Iron/Brass Founder 1872-11-05 575 ABSALOM Robert Market St,Blyth Horton 1872-08-18 £200 (Rtd) Mariner (Merchant Service) 1865-03-09 135 ACASTER Hannah Maria 1,Milk Market,Sandgate Newcastle upon Tyne 1865-02-14 £450 Widow 1863-07-30 270 ACASTER Stephen Newcastle upon Tyne 1863-07-06 £450 Victualler 1877-06-20 346 ADAMS Charles Wallsend 1877-05-30 £450 House Agent 1876-04-26 267 ADAMS Robert Wallsend 1875-12-19 £200 Engineer's Clerk 1864-08-03 303 ADAMS Thomas Kirton Tce,Elswick Newcastle upon Tyne 1864-06-13 £100 Shoemaker 1867-10-17 493 ADAMSON Israel 76,Blenheim St Newcastle upon Tyne 1867-08-03 £200 Mason 1861-03-06 104 ADAMSON Thomas Spittalshields Hexham 1860-12-26 £800 Yeoman 1878-07-18 395 ADDERLEY George Lemington 1878-06-28 £200 River Tyne Commissioners Watchman Late of Blaydon,Durham. Died in a boat on River Tyne 1871-01-26 33 ADDISON Matthew 7,Brougham Place,Scotswood Rd Newcastle upon Tyne 1870-12-18 £20 Engineer 1874-10-08 555 ADDISON Matthew Hexham 1874-08-22 £800 Innkeeper (Rtd) 1874-05-23 295 ADLER Edward Warkworth 1874-03-29 £450 Master Mariner 1865-09-13 419 ADSHEAD Aaron Bedlington 1865-07-15 £35,000 Gentleman 1876-08-17 464 ADSHEAD Christiana North Shields 1876-07-09 £3,000 Widow Late of Tynemouth 1865-08-12 361 AFFLECK Margaret 1,St.Thomas Tce. -

Northumberland Wills Index 1879 – 1899

ID DATE PROVED PAGE NUMBER SURNAME FIRST NAME[S] ABODE TOWN/VILLAGE/PARISH DATE OF DEATH VALUE OCCUPATION NOTES 1 1898-12-06 693 ABBOT Ann 64,Churchway North Shields Widow 2 1893-08-25 470 ABBOT Sarah Ropery House,Albion Row Byker 1893-07-30 £74 Widow 3 1880-01-13 15 ABBOT William 31,Alexandra Place Newcastle upon Tyne 1879-06-06 £800 Gentleman 4 1892-10-03 814 ABBOTT Henry 33,Close Newcastle upon Tyne 1892-08-23 £31 Miller Amended to £293 5 1890-10-29 763 ABBOTT John William 34,Clayton Street West Newcastle upon Tyne 1889-03-23 £90 Waiter 6 1895-06-10 467 ABERNETHY James 39,Gardener Street North Shields Master Mariner 7 1891-06-10 393 ABSALOM Margaret Dixon Cowpen Quay Blyth 1891-04-30 £30 Wife Wife of Samuel George ABSALOM 8 1879-05-03 337 ADAM George Hall 11,Albert Tce,Westmoreland Rd Newcastle upon Tyne 1879-04-02 £300 Sewing Machine Agent Late of Birmingham,Warwick. 9 1882-09-26 612 ADAMS Ann High St West Wallsend 1882-06-26 £395 Widow 10 1889-07-19 458 ADAMS Henry 209,Westgate Rd Newcastle upon Tyne 1889-06-04 £145 Bar Manager 11 1889-02-16 115 ADAMS Jane 25,Oxford St Newcastle upon Tyne 1889-01-11 £457 Wife Wife of Andrew ADAMS 12 1883-10-18 656 ADAMS Robert 7,Percy Rd Whitley 1883-08-26 £1,189 Innkeeper/Wine/Spirit Merchant Late of 18,East Clayton St,Newcastle 13 1897-03-27 185 ADAMSON Catherine 10,Trinity Chare,Quayside Newcastle upon Tyne Married Woman 14 1895-01-02 001 ADAMSON Charles Murray - - Esquire 15 1892-04-26 401 ADAMSON Hannah Garden House Cullercoats 1891-12-26 £502 Wife Wife of William ADAMSON,Esquire.Amended to -

Ibuild WP 15: Summary of Survey Results for Ovingham Bridge Closure

iBUILD WP 15: Summary of survey results for Ovingham Bridge closure Arthur Affleck During November 2014 an online survey was opened asking about the impacts of the closure of Ovingham Bridge. There were 65 responses with 35 (53.8%) from Ovingham and 30 (46.2%) from Prudhoe. The results were from a small sample of residents, less than 3% of Ovingham residents and less than 0.3% of Prudhoe residents. Not every question was applicable to all respondents, which also reduced the number of responses. Therefore the figures will not be statistically significant, but will illustrate some impacts of the closure on these residents. The responses provide evidence to show the bridge closure had an impact on certain activities. In particular around a third of respondents had been affected a lot when travelling to work, buying groceries and visiting friends and relatives. Has the closure of Ovingham Bridge affected Not at all Slightly A lot how you: Travel to work 51.0% 16.3% 32.7% Carry out your business 48.8% 34.1% 17.1% Do the school run 71.0% 16.1% 12.9% Buy groceries 28.9% 36.5% 34.6% Buy fuel 49.0% 22.4% 28.6% Access health care (GP practice, health 51.0% 26.5% 22.5% centre, dental practice) Use leisure facilities (public library, 47.8% 30.4% 21.8% swimming pool etc.) Visit friends and family 23.7% 44.1% 32.2% When asked were they using the local shops and businesses more, less or the same around 29% (18 respondents) were using the local shops less and around 14% (9 respondents) more.