Abraham Bloemaert (Gorinchem 1566 – 1651 Utrecht)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan

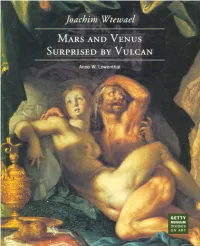

Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Anne W. Lowenthal GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Malibu, California Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Joachim Wtewael (Dutch, 1566-1638). Cynthia Newman Bohn, Editor Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan, Amy Armstrong, Production Coordinator circa 1606-1610 [detail]. Oil on copper, Jeffrey Cohen, Designer 20.25 x 15.5 cm (8 x 6/8 in.). Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum (83.PC.274). © 1995 The J. Paul Getty Museum 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Frontispiece: Malibu, California 90265-5799 Joachim Wtewael. Self-Portrait, 1601. Oil on panel, 98 x 74 cm (38^ x 29 in.). Utrecht, Mailing address: Centraal Museum (2264). P.O. Box 2112 Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs provided) courtesy of the owners unless otherwise Library of Congress indicated. Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lowenthal, Anne W. Typography by G & S Typesetting, Inc., Joachim Wtewael : Mars and Venus Austin, Texas surprised by Vulcan / Anne W. Lowenthal. Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., p. cm. Hong Kong (Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-89236-304-5 i. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638. Mars and Venus surprised by Vulcan. 2. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638 — Criticism and inter- pretation. 3. Mars (Roman deity)—Art. 4. Venus (Roman deity)—Art. 5. Vulcan (Roman deity)—Art. I. J. Paul Getty Museum. II. Title. III. Series. ND653. W77A72 1995 759-9492-DC20 94-17632 CIP CONTENTS Telling the Tale i The Historical Niche 26 Variations 47 Vicissitudes 66 Notes 74 Selected Bibliography 81 Acknowledgments 88 TELLING THE TALE The Sun's loves we will relate. -

The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 2Nd Ed

Abraham Bloemaert (Gorinchem 1566 – 1651 Utrecht) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Abraham Bloemaert” (2017). Revised by Piet Bakker (2019). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 2nd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. New York, 2017–20. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/abraham-bloemaert/ (archived June 2020). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. Abraham Bloemaert was born in Gorinchem on Christmas Eve, 1566. His parents were Cornelis Bloemaert (ca. 1540–93), a Catholic sculptor who had fled nearby Dordrecht, and Aeltgen Willems.[1] In 1567, the family moved to ’s-Hertogenbosch, where Cornelis worked on the restoration of the interior of the St. Janskerk, which had been badly damaged during the Iconoclastic Fury of 1566. Cornelis returned to Gorinchem around 1571, but not for long; in 1576, he was appointed city architect and engineer of Utrecht. Abraham’s mother had died some time earlier, and his father had taken a second wife, Marigen Goortsdr, innkeeper of het Schilt van Bourgongen. Bloemaert probably attended the Latin school in Utrecht. He received his initial art education from his father, drawing copies of the work of the Antwerp master Frans Floris (1519/20–70). According to Karel van Mander, who describes Bloemaert’s work at length in his Schilder-boek, his subsequent training was fairly erratic.[2] His first teacher was Gerrit Splinter, a “cladder,” or dauber, and a drunk. The young Bloemaert lasted barely two weeks with him.[3] His father then sent him to Joos de Beer (active 1575–91), a former pupil of Floris. -

Cornelis Cornelisz, Who Himself Added 'Van Haarlem' to His Name, Was One of the Leading Figures of Dutch Mannerism, Together

THOS. AGNEW & SONS LTD. 6 ST. JAMES’S PLACE, LONDON, SW1A 1NP Tel: +44 (0)20 7491 9219. www.agnewsgallery.com Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem (Haarlem 1562 – 1638) Venus, Cupid and Ceres Oil on canvas 38 x 43 in. (96.7 x 109.2 cm.) Signed with monogram and dated upper right: ‘CH. 1604’ Provenance Private collection, New York Cornelis Cornelisz, who himself added ‘van Haarlem’ to his name, was one of the leading figures of Dutch Mannerism, together with his townsman Hendrick Goltzius and Abraham Bloemaert from Utrecht. He was born in 1562 in a well-to-do Catholic family in Haarlem, where he first studied with Pieter Pietersz. At the age of seventeen he went to France, but at Rouen he had to turn back to avoid an outbreak of the plague and went instead to Antwerp, where he remained for a year with Gilles Coignet. The artist returned to Haarlem in 1581, and two years later, in 1583, he received his first important commission for a group portrait of a Haarlem militia company (now in the Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem). From roughly 1586 to 1591 Cornelis, together with Goltzius and Flemish émigré Karel van Mander formed a sort of “studio brotherhood” which became known as the ‘Haarlem Academy’. In the 1590’s he continued to receive many important commissions from the Municipality and other institutions. Before 1603, he married the daughter of a Haarlem burgomaster. In 1605, he inherited a third of his wealthy father-in-law’s estate; his wife died the following year. From an illicit union with Margriet Pouwelsdr, Cornelis had a daughter Maria in 1611. -

ARTIST Is in Caps and Min of 6 Spaces from the Top to Fit in Before

JOACHIM ANTHONISZ. WTEWAEL (1566 – Utrecht – 1638) Maternal Charity Signed and dated lower centre: Jo.wte.wael.fecit/Anno 1623 On panel, 22¾ x 31¼ ins. (57.8 x 79.3 cm) Provenance: (Possibly) Johan Pater and Antoinetta Pater-Wtewael, the artist’s daughter, Utrecht, until 1655 And by descent to (Possibly) Johan van Nellesteyn and Hillegonda van Nellesteyn- Pater, Utrecht, from 1655 Private collection, France, 2012 Literature: We are grateful to Anne W. Lowenthal for confirming the attribution of the painting on the basis of a colour transparency. She has also confirmed that the picture will be included in any future update of her 1986 publication, Joachim Wtewael and Dutch Mannerism. Note: This picture is being exhibited in a monographic exhibition at the Central Museum in Utrecht from February 21 – May 25 2015, the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC from June 28 – October 4, and at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, from November 1 2015 – January 31 2016. VP4581 In Christian theology charity is the most important of the three virtues. So states Saint Paul in the First Letter to the Corinthians: “And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three: but the greatest of these is charity” (I Corinthians 13:13). In practice, the word “charity” can be taken to mean “love” and in the eyes of the Church, it was both the love of God – amor dei – and love of one’s fellow-man – amor proximi. The subject of Charity had a long tradition in Christian art and by the seventeenth century it was generally represented by images of motherhood. -

Print Format

Joachim Anthonisz. Wtewael (Utrecht 1566 - Utrecht 1638) Caritas oil on panel 37 x 28 in (94 x 71.1 cm) In this painting Caritas, or Charity, is personified by the young woman in the centre of the painting, who sits breastfeeding the child in her lap. The infant, however, has turned away to look at the boy seated on the step who holds a pear which he has taken from the basket, overflowing with fruit. Both this boy, an older girl, and a grey cat are distracted by the child standing next to Caritas, who is holding a bird in his hand. Behind Caritas, peering over her shoulder, is a further figure who holds a shallow metal bowl and a spoon. Joachim Anthonisz. Wtewael has unified this multi-figured composition through the figures’ interest in each other and the bird. Despite the variety of contorted poses, a potentially fragmented scene is harmonised due to the figures’ nuanced facial expressions and reactions. In her 1986 catalogue raisonné of Wtewael’s work, Anne W. Lowenthal included the present work under ‘Problematical Attributions’ on the basis of ‘a poor photograph’.¹ However, she has since revised her opinion and, in a 1993 letter, writes ‘Having examined it after a recent cleaning, I am now confident of the 125 Kensington Church Street, London W8 7LP United Kingdom www.sphinxfineart.com Telephone +44(0)20 7313 8040 Fax: +44 (0)20 7229 3259 VAT registration no 926342623 Registered in England no 06308827 attribution to Joachim Wtewael’.² Lowenthal has dated the present work to the late 1610s or early 1620s, as the composition of an isolated figure group against a dark background was one that Wtewael used repeatedly during this period. -

Prints, and Paintings, Ed

Lot and His Daughters 1624 oil on canvas Abraham Bloemaert 167 x 232.4 cm (Gorinchem 1566 – 1651 Utrecht) signed and dated in dark paint, lower right corner: “A. Bloemaert fe. 1624” AB-100 © 2021 The Leiden Collection Lot and His Daughters Page 2 of 13 How to cite Van Tuinen, Ilona. “Lot and His Daughters” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artwork/lot- and-his-daughters/ (accessed September 26, 2021). A PDF of every version of this entry is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Lot and His Daughters Page 3 of 13 The prospect of human extinction can drive people to desperate measures. Comparative Figures The morally charged story of Lot and his daughters, recounted in Genesis 19, demonstrates just how far people will go to ensure the continuance of their lineage. The old, righteous Lot, one of Abraham’s nephews, lived in the doomed city of Sodom among its immoral citizenry. As a reward for his virtue, God spared Lot, along with his wife and two daughters, from Sodom’s destruction. During their flight, however, Lot’s wife defied God’s command and looked back. As punishment, she was turned into a pillar of salt. Lot Fig 1. Lucas van Leyden, Lot and His Daughters, 1530, engraving, eventually settled inside a cave with his daughters. -

Pleasure and Piety: the Art of Joachim Wtewael

Pleasure and Piety Te Art of Joachim Wtewael (1566 – 1638) National Gallery of Art, June 28 – October 4, 2015 Joachim Wtewael led a life as exceptional and diverse as his art. A master ful storyteller who infused his narrative paintings with emotion and wit, Wtewael was as adept at interpreting sacred stories from the Bible as he was at illustrating erotic tales from Greco- Roman mythology. He executed complex compositions with bril- liant color and fne detail on both monumental canvases and small copperplates. He could paint from imagination and from life, creating striking portraits of family members and introducing naturalistic still lifes into his genre and narrative scenes. In his self-portrait of 1601 (fg. 1), Wtewael appears as a con- fdent, well-to-do gentleman artist, clothed handsomely, with pearl and gold rings adorning his pinky fnger. At age thirty-four he was already a distinguished citizen of Utrecht, one of the oldest cities in the Nether lands, and commanded high prices from collectors eager for his work. He went on to become a founding member of the local artists’ guild and an active participant in local politics. An ardent Cal- vinist, he served on the city council during a time of religious turmoil and held various charitable positions. He was in addition a successful fax merchant 8 perhaps too successful in the eyes of one contempo- rary observer, the writer Karel van Mander, who deemed Wtewael one of the outstanding painters of his generation but lamented that he spent more time on his business than his pictures. -

Stephen Ongpin Fine Art

STEPHEN ONGPIN FINE ART ABRAHAM BLOEMAERT Gorinchem (Gorcum) 1566-1651 Utrecht Studies of the Head of a Young Woman, Legs and Hands and the Bust of a Woman Red chalk and black chalk, heightened with touches of white chalk, with framing lines in brown ink. Laid down. Numbered 125 in brown ink at the upper right. 178 x 158 mm. (7 x 6 1/4 in.) Provenance Part of an album of drawings by Bloemaert belonging to the artist André Giroux, Paris Probably the posthumous vente Giroux, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 18-19 April 1904, part of lot 175 (‘Etudes de personnages, de paysages et d’animaux. Cent trente-six dessins, la plupart exécutés à la sanguine, un certain nombre avec d’autres croquis au verso’), the album thence broken up and the drawings dispersed Private collection. Abraham Bloemaert received his artistic training in Utrecht and Paris but, unlike many of his contemporaries, never travelled to Italy. Indeed, apart from two years in Amsterdam in the early 1590s, he worked in Utrecht from 1583 until his death. Almost nothing is known of his work before 1590, however, and it is only after his brief stay in Amsterdam that he began to establish a reputation as an artist of note. Together with Cornelis van Haarlem and Joachim Wtewael, Bloemaert came to be one of the last major exponents of the Northern Mannerist tradition. Among his most important religious works are the altarpieces of God with Christ and the Virgin of 1615 in the Sint Janskerk in ’s- Hertogenbosch and an Adoration of the Magi painted in 1624 for the Jesuit church in Brussels and now in Grenoble. -

Pleasure and Piety: the Art of Joachim Wtewael (1566-1638) June 28, 2015 - October 4, 2015

Updated Wednesday, May 27, 2015 | 12:31:33 PM Last updated Wednesday, May 27, 2015 Updated Wednesday, May 27, 2015 | 12:31:33 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Pleasure and Piety: The Art of Joachim Wtewael (1566-1638) June 28, 2015 - October 4, 2015 To order publicity images: Publicity images are available only for those objects accompanied by a thumbnail image below. Please email [email protected] or fax (202) 789-3044 and designate your desired images, using the “File Name” on this list. Please include your name and contact information, press affiliation, deadline for receiving images, the date of publication, and a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned. Links to download the digital image files will be sent via e-mail. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. Joachim Anthonisz Wtewael Portrait of Steven de Witt, 1604-1610 parchment on panel 20.2 × 15.4 cm (7 15/16 × 6 1/16 in.) framed: 33 × 27 cm (13 × 10 5/8 in.) Collection Centraal Museum Utrecht, Purchase 1948 Cat. No. 1 / File Name: 3809-006.jpg Joachim Anthonisz Wtewael Self-Portrait, 1601 oil on panel 98 × 73.6 cm (38 1/2 × 29 in.) framed: 116 × 92 cm (45 11/16 × 36 1/4 in.) Collection Centraal Museum Utrecht, Purchase 1918 Cat. -

DISSOLUTE SELF-PORTRAITS in SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY DUTCH and FLEMISH ART In

ABSTRACT Title of Document: HOE SCHILDER HOE WILDER: DISSOLUTE SELF-PORTRAITS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY DUTCH AND FLEMISH ART Ingrid A. Cartwright, Ph.D., 2007 Directed By: Professor Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., Department of Art History and Archaeology In the seventeenth century, Dutch and Flemish artists presented a strange new face to the public in their self-portraits. Rather than assuming the traditional guise of the learned gentleman artist that was fostered by Renaissance topoi , many painters presented themselves in a more unseemly light. Dropping the noble robes of the pictor doctus, they smoked, drank, and chased women. Dutch and Flemish artists explored a new mode of self-expression in dissolute self-portraits, embracing the many behaviors that art theorists and the culture at large disparaged. Dissolute self-portraits stand apart from what was expected of a conventional self-portrait, yet they were nonetheless appreciated and valued in Dutch culture and in the art market. This dissertation explores the ways in which these untraditional self- portraits functioned in art and culture in the seventeenth century. Specifically, this study focuses on how these unruly expressions were ultimately positive statements concerning theories of artistic talent and natural inclination. Dissolute self-portraits also reflect and respond to a larger trend regarding artistic identity in the seventeenth century, notably, the stereotype “ hoe schilder hoe wilder ” that posited Dutch and Flemish artists as intrinsically unruly characters prone to prodigality and dissolution. Artists embraced this special identity, which in turn granted them certain freedoms from social norms and a license to misbehave. In self- portraits, artists emphasized their dissolute nature by associating themselves with themes like the Five Senses and the Prodigal Son in the tavern. -

The Spanish Style and the Art of Devotion

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Bryn Mawr College Dissertations and Theses 2009 Velázquez: The pS anish Style and the Art of Devotion Lawrence L. Saporta Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/dissertations Custom Citation Saporta, Lawrence L. "Velázquez: The pS anish Style and the Art of Devotion." Ph.D. diss., Bryn Mawr College, 2009. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/dissertations/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Velázquez: The Spanish Style and the Art of Devotion. A Dissertation submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. Department of the History of Art Bryn Mawr College Submitted by Lawrence L. Saporta Advisor: Professor Gridley McKim-Smith © Copyright by Lawrence L. Saporta, 2009 All Rights Reserved Dissertation on Diego Velázquez Saporta Contents. Abstract Acknowledgements i Image Resources iii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Jesuit Art Patronage and Devotional Practice 13 Chapter 2. Devotion, Meditation, and the Apparent Awkwardness of Velázquez’ Supper at Emmaus 31 Chapter 3. Velázquez’ Library: “an indefinite and perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries” 86 Chapter 4 Technique, Style, and the Nature of the Image 127 Chapter 5 The Formalist Chapter 172 Chapter 6 Velázquez, Titian, and the pittoresco of Boschini 226 Synthesis 258 Conclusion 267 Works Cited 271 Velázquez: The Spanish Style and the Art of Devotion. Lawrence L. Saporta, Ph.D. Bryn Mawr College, 2009 Supervisor: Gridley McKim-Smith This dissertation offers an account of counter-reformation mystical texts and praxis with art historical applicability to Spanish painting of the Seventeenth Century— particularly the work of Diego Velázquez. -

Art of the Netherlands: Painting in the Netherlands

Art of The Netherlands: Painting in the Netherlands Author Rosie Mitchell Faculty of Arts, University of Cumbria, UK Introduction As in most European countries, the first paintings in the Netherlands can be seen on the walls of religious buildings. These were largely in the form of frescoes and religious texts such as illuminated manuscripts. It was not until the 15th century, when the region gained wealth from its sea trades, that painting in the Netherlands came into its own, producing some of the most recognised and influential painters of the period. The earliest form of this painting is in the work of the Early Netherlandish painters, working through the 15th century. This work demonstrated decisive differences from Renaissance works produced in Italy at the time. The Italian influence and the Renaissance gradually affected these artworks via the Mannerist painters of Antwerp, and blossomed into the Baroque with the work of Rubens. This golden age of painting saw further distinctions in Flemish artworks with the introduction of new subjects of painting including, landscapes, still life and genre painting. The golden age of painting in the Netherlands was aided by the wealth of the region at this time as well as the presence of King Philip and the Burgundian court, which allowed court artists to flourish. The influence of art of the Netherlands on the European scene grew significantly at this point, with many of its masters gaining the respect and following of numerous Italian artists. The growth of the status of ‘artist’ in the Netherlands is demonstrated by an increase in artists who sign their name and paint self-portraits.