508 Final COMMISSION STAFF WORKING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pais Vasco 2018

The País Vasco Maribel’s Guide to the Spanish Basque Country © Maribel’s Guides for the Sophisticated Traveler ™ August 2018 [email protected] Maribel’s Guides © Page !1 INDEX Planning Your Trip - Page 3 Navarra-Navarre - Page 77 Must Sees in the País Vasco - Page 6 • Dining in Navarra • Wine Touring in Navarra Lodging in the País Vasco - Page 7 The Urdaibai Biosphere Reserve - Page 84 Festivals in the País Vasco - Page 9 • Staying in the Urdaibai Visiting a Txakoli Vineyard - Page 12 • Festivals in the Urdaibai Basque Cider Country - Page 15 Gernika-Lomo - Page 93 San Sebastián-Donostia - Page 17 • Dining in Gernika • Exploring Donostia on your own • Excursions from Gernika • City Tours • The Eastern Coastal Drive • San Sebastián’s Beaches • Inland from Lekeitio • Cooking Schools and Classes • Your Western Coastal Excursion • Donostia’s Markets Bilbao - Page 108 • Sociedad Gastronómica • Sightseeing • Performing Arts • Pintxos Hopping • Doing The “Txikiteo” or “Poteo” • Dining In Bilbao • Dining in San Sebastián • Dining Outside Of Bilbao • Dining on Mondays in Donostia • Shopping Lodging in San Sebastián - Page 51 • Staying in Bilbao • On La Concha Beach • Staying outside Bilbao • Near La Concha Beach Excursions from Bilbao - Page 132 • In the Parte Vieja • A pretty drive inland to Elorrio & Axpe-Atxondo • In the heart of Donostia • Dining in the countryside • Near Zurriola Beach • To the beach • Near Ondarreta Beach • The Switzerland of the País Vasco • Renting an apartment in San Sebastián Vitoria-Gasteiz - Page 135 Coastal -

Spain's Rapid Transition: a Case Study of Late

SPAIN’S RAPID TRANSITION: A CASE STUDY OF LATE MODERNIZATION © 2018 By Sydney Elizabeth Brown A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to begin by thanking Dr. Miguel Centellas, my advisor, who was very understanding and helpful throughout this process. Although I asked many questions, Dr. Centellas answered all of them promptly and agreed to meet with me weekly to ensure that I was on track, always encouraging me when I showed up to our meetings frantic and stressed. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr. Holly Reynolds and Dr. Will Schenck for serving as additional readers on my thesis. I am grateful for all the time my readers put in, especially because my thesis was quite lengthy. I would also like to thank Dr. Holly Reynolds for lending me some of her personal books to use in my research. Additionally, I would like to thank my family and friends for their support and encouragement throughout this whole process. Thank you all for dealing with my stress and helping to remind me not to forget to do the things I enjoy throughout this process. Finally, I would like to thank the Croft Institute and the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College for providing me with so many opportunities over the past four years. Thank you for providing me with challenging courses and making a large campus feel a lot smaller. -

Table of Contents

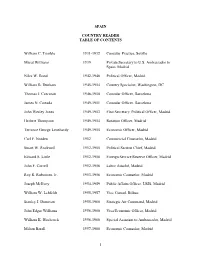

SPAIN COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS William C. Trimble 1931-1932 Consular Practice, Seville Murat Williams 1939 Private Secretary to U.S. Ambassador to Spain, Madrid Niles W. Bond 1942-1946 Political Officer, Madrid William B. Dunham 1945-1954 Country Specialist, Washington, DC Thomas J. Corcoran 1948-1950 Consular Officer, Barcelona James N. Cortada 1949-1951 Consular Officer, Barcelona John Wesley Jones 1949-1953 First Secretary, Political Officer, Madrid Herbert Thompson 1949-1954 Rotation Officer, Madrid Terrence George Leonhardy 1949-1955 Economic Officer, Madrid Carl F. Norden 1952 Commercial Counselor, Madrid Stuart W. Rockwell 1952-1955 Political Section Chief, Madrid Edward S. Little 1952-1956 Foreign Service Reserve Officer, Madrid John F. Correll 1952-1956 Labor Attaché, Madrid Roy R. Rubottom, Jr. 1953-1956 Economic Counselor, Madrid Joseph McEvoy 1954-1959 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Madrid William W. Lehfeldt 1955-1957 Vice Consul, Bilbao Stanley J. Donovan 1955-1960 Strategic Air Command, Madrid John Edgar Williams 1956-1960 Visa/Economic Officer, Madrid William K. Hitchcock 1956-1960 Special Assistant to Ambassador, Madrid Milton Barall 1957-1960 Economic Counselor, Madrid 1 Harry Haven Kendall 1957-1961 Information Officer, USIS, Madrid Charles W. Grover 1958-1960 Vice Consul, Valencia Selwa Roosevelt 1958-1961 Spouse of Archie Roosevelt, Station Chief, Madrid Phillip W. Pillsbury, Jr. 1959-1960 Junior Officer Trainee, USIS, Madrid Frederick H. Sacksteder 1959-1961 Aide to Ambassador, Madrid Elinor Constable 1959-1961 Spouse of Peter Constable, Vice Consul, Vigo Peter Constable 1959-1961 Vice Consul, Vigo Allen C. Hansen 1959-1962 Assistant Cultural Affairs Officer, USIS, Madrid Frank Oram 1959-1962 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Madrid A. -

Country Report for Spain Country-Report-Spain-2017

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 27.2.2019 SWD(2019) 1008 final COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT Country Report Spain 2019 Including an In-Depth Review on the prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances Accompanying the document COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK AND THE EUROGROUP 2019 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011 {COM(2019) 150 final} EN EN CONTENTS Executive summary 4 1. Economic situation and outlook 8 2. Progress with country-specific recommendations 15 3. Summary of the main findings from the MIP in-depth review 19 4. Reform priorities 28 4.1. Public finances and taxation 28 4.2. Financial sector 34 4.3. Labour market, education and social policies 43 4.4. Competitiveness, reforms, and investment 57 Annex A: Overview table 74 Annex B: Commission Debt Sustainability Analysis and fiscal risks 80 Annex C: Standard tables 81 Annex D: Investment guidance on cohesion policy funding 2021-2027 for Spain 87 References 94 LIST OF TABLES Table 1.1: Key economic and financial indicators - Spain 14 Table 2.1: Overall assessment of progress with 2018 CSRs 18 Table 3.1: Outward spill-over heat map for Spain 20 Table 3.2: Current account balance and net international investment position sensitivity analysis 22 Table 3.3: MIP matrix 26 Table 4.2.1: Financial soundness indicators, all banks in Spain -

Non-Iberian Spanish Nationalism Examined

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) Spring 4-30-2020 Nationalism Beyond a Nation: Non-Iberian Spanish Nationalism Examined George Ruggiero IV Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Economics Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Other Political Science Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Ruggiero IV, George, "Nationalism Beyond a Nation: Non-Iberian Spanish Nationalism Examined" (2020). Honors Theses. 1578. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1578 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nationalism Beyond a Nation: Non-Spanish Iberian Nationalism Examined ©2020 By George Ruggiero IV A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2020 Approved: Advisor: Dr. Miguel Centellas Reader: Dr. Douglass Sullivan-Gonzalez Reader: Dr. Oliver Dinius 1 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 3 Research Question and Rationale 4 Theoretical Framework 5 Research Design 6 1. Case Selection 6 2. Data 9 3. Method 10 Literature Review 11 Historical Review 11 1. Basque Country 11 2. Navarre 14 3. Catalonia 16 4. Galicia 19 Theoretical Framework 22 Data and Analysis 29 Conclusions 37 Bibliography 39 2 Abstract In this thesis, I explore differences between certain non-Spanish nationalist movements within Spain. -

Validation of Diagnostic Codes and Epidemiologic Trends of Huntington

Vicente et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis (2021) 16:77 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-01699-3 RESEARCH Open Access Validation of diagnostic codes and epidemiologic trends of Huntington disease: a population-based study in Navarre, Spain Esther Vicente1,2*† , Ainara Ruiz de Sabando2,3,4† , Fermín García3 , Itziar Gastón5, Eva Ardanaz1,6 and María A. Ramos‑Arroyo2,3 Abstract Background: There is great heterogeneity on geographic and temporary Huntington disease (HD) epidemiological estimates. Most research studies of rare diseases, including HD, use health information systems (HIS) as data sources. This study investigates the validity and accuracy of national and international diagnostic codes for HD in multiple HIS and analyses the epidemiologic trends of HD in the Autonomous Community of Navarre (Spain). Methods: HD cases were ascertained by the Rare Diseases Registry and the reference Medical Genetics Centre of Navarre. Positive predictive values (PPV) and sensitivity with 95% confdence intervals (95% CI) were estimated. Overall and 9‑year periods (1991–2017) HD prevalence, incidence and mortality rates were calculated, and trends were assessed by Joinpoint regression. Results: Overall PPV and sensitivity of combined HIS were 71.8% (95% CI: 59.7, 81.6) and 82.2% (95% CI: 70.1, 90.4), respectively. Primary care data was a more valuable resource for HD ascertainment than hospital discharge records, with 66% versus 50% sensitivity, respectively. It also had the highest number of “unique to source” cases. Thirty‑fve per cent of HD patients were identifed by a single database and only 4% by all explored sources. Point prevalence was 4.94 (95% CI: 3.23, 6.65) per 100,000 in December 2017, and showed an annual 6.1% increase from 1991 to 1999. -

Renewable Energy Systems

December 2019 Flexibility Solutions for High- Renewable Energy Systems Spain Flexibility Solutions for High- Renewable Energy Systems December 2019 Foreword Climate change effects are arising at a much faster pace than the scientific community had anticipated, increasing the need for an urgent, unprecedented and systemic change, in which we cannot allow caution. The good news is that the world is already electrifying at a record speed, driven by the competitiveness of wind and solar. Today, renewable energies are the lowest-cost and most technologically mature option to lead the transition from a polluting and obsolete energy system to a new and fully decarbonized one. Therefore, the question is no longer whether clean technologies are going to be the cornerstone of the future energy system, but rather which flexibility options will back them, and how to address the operational and market challenges that will arise. To accelerate renewable market expansion, flexibility solutions have to be harnessed. In Spain, the focus of this report and ACCIONA’s home market, these challenges are especially important. It is a market with huge renewables potential, and also less interconnected than other European countries. In all the flexibility scenarios analyzed, the study has demonstrated the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of a high-renewable system, with renewables achieving over 80% of the electricity mix by 2030, and at least 90% by 2050. The fact that wind and solar will dominate the future energy mix has special relevance in a country that currently spends €131 million per day on fossil fuel imports. With the ambitious renewable targets recently proposed, and clear paths for phased closure of coal (2020-30) and nuclear power plants (2035), Spain has become a lead country and can take advantage of the great opportunity for economic transformation that this transition represents. -

Law and Judicial Dialogue on the Return of Irregular Migrants from the European Union

LAW AND JUDICIAL DIALOGUE ON THE RETURN OF IRREGULAR MIGRANTS FROM THE EUROPEAN UNION Th is volume examines the implementation of the Return Directive from the perspective of judicial dialogue. While the role of judges has been widely addressed in European asylum law and EU law more generally, their role in EU return policy has hitherto remained underexplored. Th is volume addresses the interaction and dialogue between domestic judiciaries and European courts in the implementa- tion of European return policy. Th e book brings together leading authors from various backgrounds, including legal scholars, judges and practitioners. Th is allows the collection to off er theoretical and practical perspectives on important questions regarding the regulation of irregular migration in Europe, such as: what constitutes inadequate implementation of the Directive and under which condi- tions can judicial dialogue solve it? How can judges ensure that the right balance is struck between eff ective return procedures and fundamental rights? Why do we see diff erent patterns of judicial dialogue in the Member States when it comes to particular questions of return policy, for example regarding the use of detention? Th ese questions are more timely than ever given the shift ing public discourse on immigration and the growing political backlash against immigration courts. Th is book will be essential reading for all scholars and practitioners in the fi elds of immigration law and policy, EU law and public law. Volume 99 in the Series Modern Studies in European -

From the Library of Ian Robertson

SPAIN AND PORTUGAL: FROM THE LIBRARY OF IAN ROBERTSON BERNARD QUARITCH LTD BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 BEDFORD ROW,LONDON, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] / [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 Front cover image from no. 169 - Vivian Inside covers from no. 119 - López Title-page vignette from no. 14 - Batty Recent lists: 2021/8 The Classical Tradition 2021/7 Eccentrics, Cranks, Ousiders, Obsessives 2021/6 Women 2021/5 Art & Architecture 2021/4 Hippology - The Billmyer-Conant Collection II 2021/3 The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman part III, 1800 to 1950 2021/2 California Virtual Book Fair 2021 Recent catalogues: 1443 English Books & Manuscripts 1442 The English & Anglo-French Novel 1740-1840 1441 The Billmyer–Conant Collection — Hippology 1440 English Books & Manuscripts © Bernard Quaritch 2021 CATALOGUE 1444 SPAIN AND PORTUGAL: FROM THE LIBRARY OF IAN ROBERTSON BERNARD QUARITCH LTD MMXXI In memory of Ian Robertson (1928–2020) who sadly died as this catalogue was nearing completion SPAIN AND PORTUGAL: FROM THE LIBRARY OF IAN ROBERTSON At first sight this catalogue, of a large part of a collection mostly of travel andmilitary books concerning Spain and Portugal, may reflect diverse interests, and perhaps it should be explained in outline how and why they were accumulated and their apparent disunity.