Sina Weibo and Its Political Implications : a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trapped in a Virtual Cage: Chinese State Repression of Uyghurs Online

Trapped in a Virtual Cage: Chinese State Repression of Uyghurs Online Table of Contents I. Executive Summary..................................................................................................................... 2 II. Methodology .............................................................................................................................. 5 III. Background............................................................................................................................... 6 IV. Legislation .............................................................................................................................. 17 V. Ten Month Shutdown............................................................................................................... 33 VI. Detentions............................................................................................................................... 44 VII. Online Freedom for Uyghurs Before and After the Shutdown ............................................ 61 VIII. Recommendations................................................................................................................ 84 IX. Acknowledgements................................................................................................................. 88 Cover image: Composite of 9 Uyghurs imprisoned for their online activity assembled by the Uyghur Human Rights Project. Image credits: Top left: Memetjan Abdullah, courtesy of Radio Free Asia Top center: Mehbube Ablesh, courtesy of -

Xi Jinping's War on Corruption

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2015 The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption Harriet E. Fisher University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Harriet E., "The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption" (2015). Honors Theses. 375. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/375 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping’s War on Corruption By Harriet E. Fisher A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute for International Studies and the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2015 Approved by: ______________________________ Advisor: Dr. Gang Guo ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Peter K. Frost i © 2015 Harriet E. Fisher ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii For Mom and Pop, who taught me to learn, and Helen, who taught me to teach. iii Acknowledgements I am indebted to a great many people for the completion of this thesis. First, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Gang Guo, for all his guidance during the thesis- writing process. His expertise in China and its endemic political corruption were invaluable, and without him, I would not have had a topic, much less been able to complete a thesis. -

China Turns up Heat on Ex-Security Chief with Crash Probe

CHINA PRIME TARGET: Zhou Yongkang was head of domestic security and a member of the Communist Party Standing Politburo Committee, making him one of the most powerful people in China, until he stepped down in 2012. REUTERS/STRINGER Authorities have begun investigating a crash in 2000 that killed the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, the prime target in China’s biggest corruption scandal, Reuters source says. China turns up heat on ex-security chief with crash probe BY BENJAMIN KANG LIM, CHARLIE ZHU AND DAVID LAGUE SPECIAL REPORT 1 CHINA’S POWER STRUGGLE BEIJING/HONG KONG, SEPTEMBER 12, 2014 ittle is known about the exact circum- stances in which Wang Shuhua was Lkilled. What has been reported, in the Chinese media, is that she died in a road ac- cident sometime in 2000, shortly after she was divorced from her husband. And that at least one vehicle with a military license plate may have been involved in the crash. Fourteen years later, investigators are looking into her death. Their sudden inter- est has nothing to do with Wang herself. It has to do with the identity of her ex-hus- band – once one of China’s most powerful men and now the prime target in President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign. Investigators are probing the death of the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, China’s HUNTING TIGERS: President Xi Jinping has launched the biggest corruption crackdown since the retired security czar, a source with di- communists came to power in 1949, going after “tigers” or high-ranking officials as well as “flies”. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

WIC Template 13/9/16 11:52 Am Page IFC1

In a little over 35 years China’s economy has been transformed Week in China from an inefficient backwater to the second largest in the world. If you want to understand how that happened, you need to understand the people who helped reshape the Chinese business landscape. china’s tycoons China’s Tycoons is a book about highly successful Chinese profiles of entrepreneurs. In 150 easy-to- digest profiles, we tell their stories: where they came from, how they started, the big break that earned them their first millions, and why they came to dominate their industries and make billions. These are tales of entrepreneurship, risk-taking and hard work that differ greatly from anything you’ll top business have read before. 150 leaders fourth Edition Week in China “THIS IS STILL THE ASIAN CENTURY AND CHINA IS STILL THE KEY PLAYER.” Peter Wong – Deputy Chairman and Chief Executive, Asia-Pacific, HSBC Does your bank really understand China Growth? With over 150 years of on-the-ground experience, HSBC has the depth of knowledge and expertise to help your business realise the opportunity. Tap into China’s potential at www.hsbc.com/rmb Issued by HSBC Holdings plc. Cyan 611469_6006571 HSBC 280.00 x 170.00 mm Magenta Yellow HSBC RMB Press Ads 280.00 x 170.00 mm Black xpath_unresolved Tom Fryer 16/06/2016 18:41 [email protected] ${Market} ${Revision Number} 0 Title Page.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 6:36 pm Page 1 china’s tycoons profiles of 150top business leaders fourth Edition Week in China 0 Welcome Note.FIN.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 3:10 pm Page 2 Week in China China’s Tycoons Foreword By Stuart Gulliver, Group Chief Executive, HSBC Holdings alking around the streets of Chengdu on a balmy evening in the mid-1980s, it quickly became apparent that the people of this city had an energy and drive Wthat jarred with the West’s perception of work and life in China. -

Sopa-Scoopzhoutarget

Friday, August 30, 2013 A3 Beam me up LEADING THE NEWS K-pop stars are embracing hologram COMMERCE Oil giants technology to reach a wider audience > L I F E C 7 banned Unwelcome guest Create your dream home Health headache from new Aquino cancels visit to China: Chic, stylish furniture Migraines can cause INVESTMENT TEAMS TO BE REINED IN Beijing says he was never and accessories for permanent brain damage projects invited in the first place discerning buyers and raise risk of strokes Commerce Ministry targets extravagance by delegations sent Foreign direct investment is a Previously, investment jun- key economic indicator used to kets were believed to be immune > LEA D ING T HE N EWS A 3 > 20-PAG E SPE CIA L REP O R T > WORLD A15 to Hong Kong and Macau to seek investment for their regions gauge officials’ performance, and from the campaign against offi- Beijing makes state ................................................ dozens of delegations from local cial extravagance. overstated the number of partici- His remarks followed the flag- governments flock to Hong Kong The The People’s Daily said busi- energy companies pay Daniel Ren pants and the value of deals ship newspaper’s harsh criticism every year to seek such invest- ness delegations stayed in five- [email protected] phenomenon the price for failing to signed during their promotional on Monday of investment dele- ments. star hotels and invited business- activities. gations travelling to Hong Kong. Yao admitted that the delega- reflects a severe men to expensive restaurants, meet pollution targets The Ministry of Commerce has “They were desperate to get This was the first time that a tions played a positive role in level of spending as much as 1,000 yuan pledged to rein in extravagance abig number of foreign business- Communist Party mouthpiece spurring the nation’s economic (HK$1,260) per head for a break- ............................................... -

Weibo's Role in Shaping Public Opinion and Political

Blekinge Institute of Technology School of Computing Department of Technology and Aesthetics WEIBO’S ROLE IN SHAPING PUBLIC OPINION AND POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN CHINA Shajin Chen 2014 BACHELOR THESIS B.S. in Digital Culture Supervisor: Maria Engberg Chen 1 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................2 2. INTERNET AND MICROBLOGGING IN CHINA ......................................................5 2.1 INTERNET, MEDIA AND POLITICAL LANDSCAPE IN CHINA: AN OVERVIEW .......................... 5 2.2 MICROBLOGGING AND CHINESE WEIBO .........................................................................7 2.3 SINA WEIBO: THE KING OF MICROBLOGGING IN CHINA ................................................... 8 3. DOMINANT FEATURES OF WEIBO IN SHAPING PUBLIC OPINION AND POLITICAL SPHERE ........................................................................................................10 3.1 INFORMATION DIFFUSION ............................................................................................11 3.2 OPINION LEADERS AND VERIFIED IDENTITY ..................................................................12 3.3 PLATFORM FOR FREE SPEECH, COLLECTIVE VOICE AND EXPOSURE ................................. 14 3.4 PARTICIPATION OF MASS MEDIA AND GOVERNMENT ......................................................15 4. CASE STUDIES ..............................................................................................................18 4.1 -

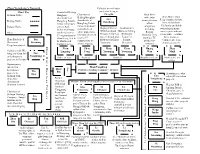

Zhou Yongkang's Network

Zhou Yongkang’s Network Colluded on real estate Chart Key Controlled Beijing project w/ Feng in Sichuan Native Honghan; Chairman of Chengdu Zhou Bin’s Zhan Minli, Zhou shareholder of Beijing Honghan; wife, who Sun Feng’s mother-in-law, Beijing Native Hongfeng Potash shareholder of managed many Jiancheng lives in Southern mines in Sichuan, Hongfeng Potash of his California and holds Jiangsu Native owned Audi mines in Sichuan; companies, ` Deputy Chief of Established A dealer in Jiangsu; controlled real including ownership in many— Wuxi Land and Business Selling Other involved in over estate projects in Beijing some reports indicate Resources Bureau; Wuliangye at least nine—of Zhou 37 corporations w/ Chengdu involved Zhongxu; Also travelled back and Liquor in Bin’s business Zhou Feng; tied to in over 37 started a TV Zhou Bin helped Dai forth to visit Zhou Jiangsu; ventures; she is an Li Hualin and corporations w/ production Dai secure Xiaoming Yonakang Deceased American citizen Kunlun Energy Zhou Lingying company Pengzhou project Zhou Bin’s Business Partners Business Bin’s Zhou Zhou Zhou Zhou Zhou Huang Zhan Colluded with Wu Lingying Feng Yuanqing Yuanxing Wan Minli Guo Bing and Zhou Bin Yongxiang on hydropower Sister-in-Law Nephew Brothers Daughter-in-Law Mother-in-Law projects in Sichuan of Son Businessman, invested in Son Zhou Yongkang hydropower Zhou Politburo Standing Committee Member Wu Bin projects in Bing A soothsayer, who Cao Sichuan with advised Li on urban Zhou Bin; Former Yongzheng projects; chairman of Chairman Major Zhou Surrogates/Secretaries in Sichuan Zhongxu Limited of Beijing Head of PSB in Zhongxu Guo Li Li Wu Jinjiang District, Yangguang Yongxiang Chongxi Chuncheng Tao Chengdu, gave Li Chairman of Petroleum Sichuan Hanlong illegal passports Liu and Natural Former Vice- Former Deputy Mayor of Chengdu; Company. -

Communist Party Controls the Gun in China: Retelling Political Control Over the PLA

Communist Party Controls the Gun in China: Retelling Political Control Over the PLA Monika Chansoria n perhaps the largest military reforms being executed in many decades Iof the recorded history of China’s military modernisation, three new military branches were created on 31 December 2015. The Chinese President Xi Jinping, who is also the Chairman of the most powerful military body, the Central Military Commission (CMC), founded and conferred military flags to the three newly constituted wings, namely, General Command of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)Rocket Force, and Strategic Support Force. Xi simultaneously named the commanders and respective political commissars for all the three branches. The reforms have specifically been directed at the military leadership and command system. The PLA’s four traditional ‘general departments’ that formerly served as both the headquarters of the PLA (PLA), and as a joint staff for the entire military, stand dismantled and have been replaced by 15 new CMC functional departments. Simultaneously, the seven military regions (MRs) (军 区) have ceased to exist and paved way for five theatre commands Dr Monika Chansoria is a Tokyo-based Resident Visiting Fellow at The Japan Institute of International Affairs (JIIA). She is also a Senior Fellow and Head of the China-study Programme, Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi. 2 • Monika Chansoria (战 区) instead. More importantly, according to the guideline released by the CMC, it has become in-charge of the overall administration of the PLA, People’s Armed Police, militia, and reserves. While the freshly constituted joint theatre commands focus on combat preparedness, the services continue to remain in-charge of overall development. -

Chinese Politics in the Xi Jingping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership

CHAPTER 1 Governance Collective Leadership Revisited Th ings don’t have to be or look identical in order to be balanced or equal. ڄ Maya Lin — his book examines how the structure and dynamics of the leadership of Tthe Chinese Communist Party (CCP) have evolved in response to the chal- lenges the party has confronted since the late 1990s. Th is study pays special attention to the issue of leadership se lection and composition, which is a per- petual concern in Chinese politics. Using both quantitative and qualitative analyses, this volume assesses the changing nature of elite recruitment, the generational attributes of the leadership, the checks and balances between competing po liti cal co ali tions or factions, the behavioral patterns and insti- tutional constraints of heavyweight politicians in the collective leadership, and the interplay between elite politics and broad changes in Chinese society. Th is study also links new trends in elite politics to emerging currents within the Chinese intellectual discourse on the tension between strongman politics and collective leadership and its implications for po liti cal reforms. A systematic analy sis of these developments— and some seeming contradictions— will help shed valuable light on how the world’s most populous country will be governed in the remaining years of the Xi Jinping era and beyond. Th is study argues that the survival of the CCP regime in the wake of major po liti cal crises such as the Bo Xilai episode and rampant offi cial cor- ruption is not due to “authoritarian resilience”— the capacity of the Chinese communist system to resist po liti cal and institutional changes—as some foreign China analysts have theorized. -

Chapter 3 China: Xi Jinping's Administration— Proactive Policies

Chapter 3 China: Xi Jinping’s Administration— Proactive Policies at Home and Abroad or China, 2014 was a year when initiatives of the Xi Jinping administration Fcame to the forefront. In domestic politics, it was a year of important changes, as the anti-corruption campaign continued to make itself felt, resulting, for example, in Zhou Yongkang, a former member of the Politburo Standing Committee, and Xu Caihou, former vice chairman of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Military Commission (CMC), being expelled from the party. Xi Jinping, who was already president as well as general secretary of the party, took the position of chairman of the new National Security Commission and created a number of small leading groups, part of his efforts to strengthen his structural authority. Meanwhile elements of instability grew as well, such as the number of bombings that took place in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, and the CPC is cracking down vigorously. President Xi has assertively engaged in foreign policy, leading at times to strong unilateral positions such as China’s location of oil drilling equipment in the South China Sea. China is seeking to form “a new type of major-power relations” with the United States, but China’s actions in the South China Sea and the confrontation over cyber spying make it unclear whether China will be able to achieve the kind of US-China relations it desires. President Xi is also engaging in periphery diplomacy, seeking to ensure China’s peaceful development by reinforcing its economic relations with its neighbors and calling for an Asian New Security Concept, while strengthening its criticism of the system of alliances centered on the United States. -

Cleaning the Security Apparatus Before the Two Meetings

ASIA PROGRAMME CLEANING THE SECURITY APPARATUS BEFORE THE TWO MEETINGS BY ALEX PAYETTE PH.D, CEO CERCIUS GROUP ADJUNCT PROFESSOR, GLENDON COLLEGE MAY 2020 ASIA FOCUS #139 l’IRIS ASIA FOCUS #139 – ASIA PROGRAMME / May 2020 n April 19 2020, Sun Lijun 孙力军 was put under investigation. Sun is the mishu of Meng Jianzhu 孟建柱, Party secretary of the Central Political and Legal Affairs o Commission [zhengfa] from 2012 to 2017, and a close ally of Politburo member Han Zheng 韩正, who is also a full member of Jiang Zemin’s 江泽民 Shanghai Gang 上海帮 . His arrest, which happened only one day after 15 pro-democracy activists were arrested in Hong Kong1, almost coincided with his return from Wuhan – as part of the Covid-19 containment steering group 中央赴湖北指导组. To this effect, it is evident that Sun’s investigation and arrest have been in motion for quite a while now. With Sun out of play, the former public security “tsar” Zhou Yongkang 周永康 has effectively lost most of his tentacles on the public security system. That said, Sun’s arrest might not even be the most important news shaking up the public security apparatus ahead of the upcoming “Two Meetings” 两会. CUTTING THE ROOTS As it is customary with Cadres working for public security, State security and national Defence, Sun Lijun’s public profile is quite limited. Sun, who studied in Australia, majored in public health and urban management, a very interesting choice especially considering the current pandemic. Sun was primarily active in Shanghai, and held a number of notable posts in his career including: • Director of the Hong Kong affairs office of the Ministry of Public Security from 2016 until his arrest; • Deputy director of the infamous “610” unit 中央610办公室– also known as the Central Leading Group on Preventing and Dealing with Heretical Religions 中央防范 和处理邪教问题领导小组2; • Director of the No.