Urban Water Supply: Contestations and Sustainability Issues in Greater Bangalore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangalore for the Visitor

Bangalore For the Visitor PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 12 Dec 2011 08:58:04 UTC Contents Articles The City 11 BBaannggaalloorree 11 HHiissttoorryoofBB aann ggaalloorree 1188 KKaarrnnaattaakkaa 2233 KKaarrnnaattaakkaGGoovv eerrnnmmeenntt 4466 Geography 5151 LLaakkeesiinBB aanngg aalloorree 5511 HHeebbbbaalllaakkee 6611 SSaannkkeeyttaannkk 6644 MMaaddiiwwaallaLLaakkee 6677 Key Landmarks 6868 BBaannggaalloorreCCaann ttoonnmmeenntt 6688 BBaannggaalloorreFFoorrtt 7700 CCuubbbboonPPaarrkk 7711 LLaalBBaagghh 7777 Transportation 8282 BBaannggaalloorreMM eettrrooppoolliittaanTT rraannssppoorrtCC oorrppoorraattiioonn 8822 BBeennggaalluurruIInn tteerrnnaattiioonnaalAA iirrppoorrtt 8866 Culture 9595 Economy 9696 Notable people 9797 LLiisstoof ppee oopplleffrroo mBBaa nnggaalloorree 9977 Bangalore Brands 101 KKiinnggffiisshheerAAiirrll iinneess 110011 References AArrttiicclleSSoo uurrcceesaann dCC oonnttrriibbuuttoorrss 111155 IImmaaggeSS oouurrcceess,LL iicceennsseesaa nndCC oonnttrriibbuuttoorrss 111188 Article Licenses LLiicceennssee 112211 11 The City Bangalore Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) Bangalore — — metropolitan city — — Clockwise from top: UB City, Infosys, Glass house at Lal Bagh, Vidhana Soudha, Shiva statue, Bagmane Tech Park Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) Location of Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) in Karnataka and India Coordinates 12°58′′00″″N 77°34′′00″″EE Country India Region Bayaluseeme Bangalore 22 State Karnataka District(s) Bangalore Urban [1][1] Mayor Sharadamma [2][2] Commissioner Shankarlinge Gowda [3][3] Population 8425970 (3rd) (2011) •• Density •• 11371 /km22 (29451 /sq mi) [4][4] •• Metro •• 8499399 (5th) (2011) Time zone IST (UTC+05:30) [5][5] Area 741.0 square kilometres (286.1 sq mi) •• Elevation •• 920 metres (3020 ft) [6][6] Website Bengaluru ? Bangalore English pronunciation: / / ˈˈbæŋɡəɡəllɔəɔər, bæŋɡəˈllɔəɔər/, also called Bengaluru (Kannada: ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು,, Bengaḷūru [[ˈˈbeŋɡəɭ uuːːru]ru] (( listen)) is the capital of the Indian state of Karnataka. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 31282-IN PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF US$216 MILLION TO THE REPUBLIC OF INDIA FOR THE KARNATAKA MUNICIPAL REFORM PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized FEBRUARY 14,2006 Infrastructure and Energy Sector Unit India Country Management Unit South Asia Region This document as a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective February 1,2006) Currency Unit = Indian Rupee (INR) Rs.44.0 = US$l US$1.510 = SDRl FISCAL YEAR April 1 - March 31 Comptroller and Auditor General C&AG of India CAO Chief Accounts Officer CAS Country Assistance Strategy CBO Community Based Organization Capacity Enhancement Needs cc City Corporation CENA Assessment CIP Catital Investment Plans CMC Citv MuniciDal Councils GIS Geographical Information System GO Government Order Go1 Government of India GoK Government of Karnataka ~ International Bank for IBRD Reconstruction and Development ICB International Competitive Bidding International Development IDA Association IEC Information Education Communication IFA Initial Financial Assessment IRR Internal Rate of Return Integrated Development of Small IDSMT and Medium Towns IT Information Technology Japanese Bank for International JBIC Cooperation KHB Karnataka Housing Board KMA Karnataka Municipalities Act KMCA Karnataka Municipal Corporation Act Karnataka Municipal Reform KMRP Project KSAD Karnataka State Accounts Department Karnataka Town & Country Planning KSCB Karnataka Slum Clearance Board KTCP Act Karnataka State Remote Sensing Karnataka Urban Infrastructure KSRSAC Applications Centre KUIDFC Development Finance Corp. -

Wetlands: Treasure of Bangalore

WETLANDS: TREASURE OF BANGALORE [ABUSED, POLLUTED, ENCROACHED & VANISHING] Ramachandra T.V. Asulabha K. S. Sincy V. Sudarshan P Bhat Bharath H. Aithal POLLUTED: 90% ENCROACHED: 98% Extent as per BBMP-11.7 acres VIJNANAPURA LAKE Encroachment- 5.00acres (polygon with red represents encroachments) ENVIS Technical Report: 101 January 2016 Energy & Wetlands Research Group, CES TE 15 Environmental Information System [ENVIS] Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore - 560012, INDIA Web: http://ces.iisc.ernet.in/energy/, http://ces.iisc.ernet.in/biodiversity Email: [email protected], [email protected] ETR 101, Energy & Wetlands Research Group, CES, IISc WETLANDS: TREASURE OF BANGALORE [ABUSED, POLLUTED, ENCROACHED & VANISHING] Ramachandra T.V. Asulabha K. S. Sincy V. Sudarshan P Bhat Bharath H. Aithal © Energy & Wetlands Research Group, CES TE15 Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science Bangalore 560012, India Citation: Ramachandra T V, Asulabha K S, Sincy V, Sudarshan Bhat and Bharath H.Aithal, 2015. Wetlands: Treasure of Bangalore, ENVIS Technical Report 101, Energy & Wetlands Research Group, CES, IISc, Bangalore, India ENVIS Technical Report 101 January 2016 Energy & Wetlands Research Group, Centre for Ecological Sciences, TE 15 New Bioscience Building, Third Floor, E Wing Indian Institute of Science Bangalore 560012, India http://ces.iisc.ernet.in/energy, http://ces.iisc.ernet.in/biodiversity Email: [email protected], [email protected] Note: The views expressed in the publication [ETR 101] are of the authors and not necessarily reflect the views of either the publisher, funding agencies or of the employer (Copyright Act, 1957; Copyright Rules, 1958, The Government of India). -

Urban Planning in Vernacular Governance

The London School of Economics and Political Science Urban Planning in Vernacular Governance --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Land use planning and violations in Bangalore Jayaraj Sundaresan A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography and Environment of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, December 2013 1 of 3 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 102,973 words. I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Amit Desai and Dieter Kursietis at various stages. 2 of 3 Abstract Using a relational state-society framework, this research examines the relationship between land use violations and the urban planning process. This thesis seeks to answer how and why land use violations in the non-poor neighbourhoods of Bangalore are produced, sustained and contested in spite of the elaborate planning, implementation and enforcement mechanisms present in Bangalore. -

Lost Heritage of Fort Settlement

LOST HERITAGE OF FORT SETTLEMENT -A CASE STUDY ON DEVANAHALLI FORT, BANGALORE, KARNATAKA, INDIA. -INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON SUSTAINABILITY IN BUILT ENVIRONMENT -3 RD & 4 TH JANUARY 2020, ORGANISED BY AURORA GROUP OF ARCHITECTURE COLLEGES, HYDERABAD. Authors - Samaa Hasan, Arshia Meiraj, Saman Khuba K,3rd yr Students of Aditya Academy of Architecture and Design, Co Authors - Guided by Subanitha R, Anupadma R, Assistant Professor, Aditya Academy of Architecture and Design, Mentored by Dr. K N Ganesh Babu Principal, Aditya Academy of Architecture and Design, Yelahanka, Bangalore. Samaa Hasan, Arshia Meiraj, Saman Khuba K, Authors – Students of Aditya Academy of Architecture and Design, Yelahanka, Bangalore. Co Authors - Guided by Subanitha R, Anupadma R, Assistant Professor, Aditya Academy of Architecture and Design, Mentored by Dr. K N Ganesh Babu Principal, Aditya Academy of Architecture and Design, Yelahanka, Bangalore. LOST HERITAGE OF FORT SETTLEMENT - A CASE STUDY ON DEVANAHALLI FORT, INTRODUCTION: With rapid growth in population, urbanization seems to wrap its arms around the heritage fabric, assimilating within it all its cultural charm, its traditions and its very existence. Intense vandalization of rural fabric with replacement of modern era buildings seems to supersede the cultural techniques and the sense of tradition in the settings. In the expansive demand for jobs, opportunities, and buildings to accommodate all of it, the places which symbolize the local history and its significance becomes miniscule and nullified by the ferocious wave of urbanization. This paper is an effort to study and exhibit the potential of a victim of urbanization, Devanahalli fort and to forward few guidelines to save and retain its originality to supply it for the knowledge of future generation to understand the local history. -

Bangalore Travel Guide PDF Download | Map, Tourist Places

Created Date: 25 October 2014 Best of Bangalore Recommended by Indian travellers Busy journey Bangalore visit was a good and it was an official visit. As Prathee there was a quiet good stay. p Travelling by Shatabdi from Chennai is the best fastest... 421 travel stories about Bangalore by Indian travellers Guide includes:About destination | Top things to do | Best accommodations | Travelling tips | Best time to visit About Bangalore Bangalore or Bengaluru, popularly known as the Silicon Valley of India, is the capital city of the South Indian state of Karnataka. Situated on the Deccan Plateau, in the south-eastern part of the state, the city experiences a moderate climate. History of Bangalore From the 50s, this beautiful city of gardens, also known as the Garden City, with its temperate climate, lovely bungalows, tree-lined broad avenues and laid back ambience was a pensioner's paradise. Bengaluru derives its name from the Kannada words ‘benda kalluru’, which means the land of boiled beans. According to legend, Veera Ballara, the Hoysala king, once lost his way during a hunting expedition. Wandering around, he met an old lady who gave him boiled beans to eat. In order to show his gratitude, he named the place, Benda Kalluru. Some historians believe that the name was derived from the ‘benga’ or ‘ven kai’ tree. Page 1/16 Bangalore, as we know it today, was formed by Kempe Gowda. Formerly, Bangalore was ruled by a number of rulers and dynasties, including the Vijayanagara Empire and Tipu Sultan. A number of temples and monuments, which were built in the earlier days, are still a part of the city’s landscape. -

(Lakes) in Urban Areas- a Case Study on Bellandur Lake of Bangalore Metropolitan City

IOSR Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering (IOSR-JMCE) e-ISSN: 2278-1684,p-ISSN: 2320-334X, Volume 7, Issue 3 (Jul. - Aug. 2013), PP 06-14 www.iosrjournals.org Scenario of Water Bodies (Lakes) In Urban Areas- A case study on Bellandur Lake of Bangalore Metropolitan city Ramesh. N 1, Krishnaiah. S2 1(Department of Civil Engineering, Government Engineering College, K.R.Pet-571 426, Karnataka) 2(Department of Civil Engineering, JNTUA College of Engineering, Anantapur -515 002, Andra pradesh) Abstract: Environment is made up of natural factors like air, water and land. Each and every human activities supports directly/indirectly by natural factors. India is facing a problem of natural resource scarcity, especially of water in view of population growth and economic development. Due to growth of Population, advancement in agriculture, urbanization and industrialization has made surface water pollution a great problem and decreased the availability of drinking water. Many parts of the world face such a scarcity of water. Lakes are important feature of the Earth’s landscape which are not only the source of precious water, but provide valuable habitats to plants and animals, moderate hydrological cycles, influence microclimate, enhance the aesthetic beauty of the landscape and extend many recreational opportunities to humankind .For issues, perspectives on pollution, restoration and management of Bellandur Lake Falls under Bangalore Metropolitan city is very essential to know their status but so far, there was no systematic environmental study carried out. Hence now the following studies are essential namely Characteristics, Status, Effects (on surrounding Groundwater, Soil, Humans health, Vegetables, Animals etc.,), resolving the issues of degradation, preparation of conceptual design for restoration and management. -

Metro Cities Atm List City Address

METRO CITIES ATM LIST CITY ADDRESS BANGALORE AEGIS LIMITED RELIANCE JIO PVT LTD C/O MIND COMP TECH PARK ROAD NO 7 EPIP AREA WHITEFIELD BEHIND L&T INFOTECH BENGALURU KT IN 560066 FINANCE AND BUSINESS OPERATIONS TEAM INCTURE TECHNOLOGIES PVT LTD 3RD FLOOR, BLOCK A, SALARPURIA AURA KADUBEESANAHALLI OUTER RING ROAD BANGALORE ‘SILVER PALMS’, #3, PALMGROVE ROAD, VICTORIA LAYOUT, BENGALURU - 560047 NO.73/1-1, GROUND FLOOR, KRISHNA INFANTRY ROAD, BENGALURU-560001 AXIS BANK LTD MAIN BRANCH NO 9 M G ROAD BLOCK A BANGALORE 560 001 AXIS BANK LTD MAIN BRANCH NO 9 M G ROAD BLOCK A BANGALORE 560 001 AXIS BANK ATM VALTECH 30/A GROUND FLOOR J P NAGAR SARAKKI 3RD PHASE 1ST MAIN ROAD 3RD STAGE INDUSTRIAL SUBURB BANGALORE AXIS BANK ATM ANAGHA NO4 DEVASANDRA NEW BEL RD NEXT TO COFFEE DAY ANJANYA TEMPLE STREET BANGALORE 560012 AXIS BANK ATM ANAGHA NO4 DEVASANDRA NEW BEL RD NEXT TO COFFEE DAY ANJANYA TEMPLE STREET BANGALORE 560012 AXIS BANK ATM ASC CENTER & COLLEGE REGIMENTAL SHOPPING COMPLEX ( SOUTH) ASC CENTER & COLLEGE AGRAM BANGALORE 560 007 AXIS BANK ATM ASC CENTER & COLLEGE REGIMENTAL SHOPPING COMPLEX ASC CENTER & COLLEGE AGRAM BANGALORE 560 007 AXIS BANK ATM ASC CENTER & COLLEGE REGIMENTAL SHOPPING COMPLEX ASC CENTER & COLLEGE AGRAM BANGALORE 560 007 AXIS BANK ATM SENA POLICE CORPS KENDRA AUR SCHOOL (CMP CENTER & SCHOOL) BANGALORE 560025 AXIS BANK ATM TATA ELEXSI LTD ITPL ROAD WHITEFIELD BANGALORE 560 048 AXIS BANK ATM GOLFLINKS SOFTWARE PARK 24/7 CUSTOMER GOLFLINKS SOFTWARE PARK PVT LTD 2/13 AND 5/1 CHALLAGHATTA VILLAGE VARTHUR HOBLI BANGALORE 560 071 -

Large-Scale Urban Development in India - Past and Present

Large-Scale Urban Development in India - Past and Present Sagar S. Gandhi Working Paper #35 November 2007 | Collaboratory for Research on Global Projects The Collaboratory for Research on Global Projects at Stanford University is a multidisciplinary cen- ter that supports research, education and industry outreach to improve the sustainability of large in- frastructure investment projects that involve participants from multiple institutional backgrounds. Its studies have examined public-private partnerships, infrastructure investment funds, stakeholder mapping and engagement strategies, comparative forms of project governance, and social, political, and institutional risk management. The Collaboratory, established in September 2002, also supports a global network of schol- ars and practitioners—based on five continents—with expertise in a broad range of academic disci- plines and in the power, transportation, water, telecommunications and natural resource sectors. Collaboratory for Research on Global Projects Yang & Yamazaki Energy & Environment (Y2E2) Bldg 473 Via Ortega, Suite 242 Stanford, CA 94305-4020 http://crgp.stanford.edu 2 About the Author Sagar Gandhi1 is a Building Information Modeling expert working with DPR Construction Inc. He is interested in implementation of BIM tools in practice for large scale developments. He has an ex- perience in Indian Construction industry for past 5 years and has been a successful partner at Gan- dhi Construction. He worked closely with Dr. Orr on understanding the urban development in India. Mr. Gandhi holds a Masters in Construction Engineering and Management from Stanford Univer- sity and B.E. in Civil Engineering from Maharashtra Institute of Technology, Pune University.. 1 [email protected] 3 Index 1. Acknowledgement 3 2. Abstract 4 3. -

Kent1195648204.Pdf (8.4

HIGH TECHNOLOGY AND INTRA-URBAN TRANSFORMATIONS: A CASE STUDY OF BENGALURU, INDIA A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Rajrani Kalra December, 2007 Dissertation Written by Rajrani Kalra B.A., University of Delhi, 1993 M.A., University of Delhi, 1995 B.Ed., University of Delhi, 1998 M.Phil. University of Delhi, 1999 M.A., The University of Akron, 2003 Ph. D., Kent State University, 2007 Approved by ________________________________Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Prof David H Kaplan _____________________________ Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Prof Emeritus S.M.Bhardwaj _________________________________ Dr Shawn Banasick _________________________________ Prof David McKee Accepted by __________________________________, Chair, Department of Geography Prof Jay Lee __________________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Dean Jerry Feezel ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES vi LIST OF TABLES x ACKNOWLEDGEMENT xii DEDICATION xvi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 INTRODUCTION 1 BENGALURU: The STUDY AREA 5 WHY BENGALURU IS MY STUDY AREA? 10 BACKROUND OF THE STUDY 10 RESEARCH QUESTIONS 13 RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY 14 OUTLINE OF DISSERTATION 22 CHAPTER 2: HIGH-TECHNOLOGY IN INDIAN CONTEXT 24 INTRODUCTION 24 WHAT IS HIGH- TECHNOLOGY? 26 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK OF HIGH-TECHNOLOGY. 28 HIGH-TECHNOLOGY AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 34 HIGH –TECHNOLOGY AND DEVELOPING COUNTRIES 36 HIGH –TECHNOLOGY AND REGIONAL DISPARITIES IN INDIA39 iii -

Public Space and Life in an Indian City: the Politics of Space in Bangalore

Public Space and Life in an Indian City: The Politics of Space in Bangalore by Salila P.Vanka A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Urban and Regional Planning) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Gavin M. Shatkin, Co-Chair Associate Professor Scott D. Campbell, Co-Chair Associate Professor William Glover Associate Professor David E. Thacher For Siddharth & Arnav ii Acknowledgements Thanks to Gavin for his invaluable guidance, unwavering support and compassion through the dissertation process. Scott, whose own work inspired me to explore the world of planning theory. Will and David, whose motivated teaching illuminated the path of my work. Susan, for setting me on the path of planning research, first in UT-Austin and later in doctoral studies. Barjor, for my first job as an urban researcher in CEPT. Shrawan, for his enthusiasm and encouragement. To my mother and father, for making all this possible. Siddharth and Arnav, who taught me to celebrate life at all times. Sai, for his help through my studies. Lalitha attayya, for rooting for me all along. Sushama, Ragini, Sapna and Alpa – my strong companions for life. Becky, Sabrina and Sahana, who reflect the best in their mothers. Pranav, for keeping me focused in the crucial last lap to the finish line. Sweta, who inspires me by example. Parul and Chathurani, my friends and cheerleaders. Nandini, Neha, Nina, Prabhakar, Hamsini, Prasad, Bill, Dhananjay and Cathy for their kind help. To Deirdra and Doug, for the most enjoyable exam preparation (and food) sessions. -

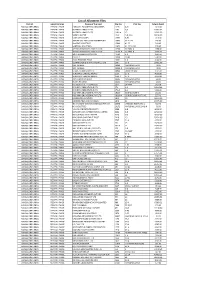

List of Allotment Files District Industrial Area Name of the Unit File No

List of Allotment Files District Industrial Area Name of the Unit File No. Plot No. Extent (Sqm) BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE CARNATIC ENGINEERING INDUSTRIES 11271 6-F1 1012.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE INGERSOLL-RAND P LTD 1161 7,8 42864.04 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE INGERSOLL-RAND P LTD 1161-A 12 16262.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE WIPRO LIMITED 1243 9-B,10-A 38240.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE VIVEK ASSOCIATES 12670 6-F2 1012.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE AARVEE CNC PRECISION ENGINEERING 13658 SY.41-P4 208.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE JAYATHE INDUSTRIES 13666 41-P3 240.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE SANTOSH INDUSTRIES 13673 41-P2 SY.NO 278.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE APPOLO POWER SYSTEMS PVT LTD 13708 28-PART A 1768.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE APPOLO POWER SYSTEMS PVT LTD 13708-A 28-PART B 2596.04 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE AOTS ALUMNI ASSOCIATION 13748 6-G 3501.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE K S R T C 13830 20-A1 5702.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE GOVT PRINTING PRESS 13831 6-E 2722.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE GEMINI DYEING & PRINTING MILLS LTD 1397 16-B 18466.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE SMT.KAMALA 14949 MARGINAL LAND 70.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE SMT.KAMALA 14949-A MARGINAL LAND 70.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE LT.COL. SHASHIDHAR V S 14952 Under HT Line 3717.47 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE SUNDAR CHEMICALS WORKS 1530 27-B 4030.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE SUNDAR CHEMICALS WORKS 1530-A 27-A 4355.00 BANGALORE URBAN PEENYA I PHASE AJAY KUMAR BHOTIKA 16215