World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Between 1. Sri N Shankarappa S/O Late Narasimaiah, Aged

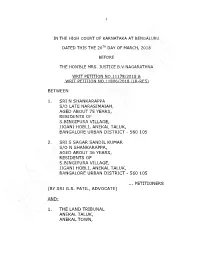

1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA AT BENGALURU DATED THIS THE 20 TH DAY OF MARCH, 2018 BEFORE THE HON'BLE MRS. JUSTICE B.V.NAGARATHNA WRIT PETITION NO.11178/2018 & WRIT PETITION NO.11806/2018 (LR-RES) BETWEEN 1. SRI N SHANKARAPPA S/O LATE NARASIMAIAH, AGED ABOUT 75 YEARS, RESIDENTS OF S.BINGIPURA VILLAGE, JIGANI HOBLI, ANEKAL TALUK, BANGALORE URBAN DISTRICT - 560 105 2. SRI S SAGAR SANDIL KUMAR S/O N SHANKARAPPA, AGED ABOUT 36 YEARS, RESIDENTS OF S.BINGIPURA VILLAGE, JIGANI HOBLI, ANEKAL TALUK, BANGALORE URBAN DISTRICT - 560 105 ... PETITIONERS (BY SRI G.S. PATIL, ADVOCATE) AND: 1. THE LAND TRIBUNAL ANEKAL TALUK, ANEKAL TOWN, 2 BENGALURU URBAN DISTRICT, REPRESENTED BY ITS CHAIRMAN - 562 106. 2. SRI SYED AZIM SAHIB SINCE DEAD BY HIS LRS 2(a) SMT. ATHIYA MUBEEN W/O LATE SYED MEHBOOB AGED ABOUT 55 YEARS, R/AT NO. 50/1, RANOJIRAO ROAD, MOHAMMADAN BLOCK, BASAVANAGUDI, BENGALURU - 560 004. 2(b) SRI SYED ATHARULLA @ NAWAB JAAN S/O LATE SYED AZIM SAHIB AGED ABOUT 72 YEARS, R/AT NO. 1674, 1ST CROSS, SHAHEED NAGAR, KOLAR TOWN - 563 101. 2(c) SRI ZIYAULLA @ JAANI BASHA S/O LATE SYED AZIM SAHIB, AGED ABOUT 70 YEARS, R/AT NO. 50/1, RANOJIRAO ROAD, MOHAMMADAN BLOCK, BASAVANAGUDI, BENGALURU - 560 004. 2(d) SRI MOHAMMED SANAULLA H/O LATE MEHRUNBI AGED ABOUT 70 YEARS, R/AT NO. 14/19C, 9TH A MAIN, 3RD CROSS, BTM I STAGE, BTM LAYOUT, BENGALURU - 560 029. 3 2(e) SRI MOHAMMED INAYATHULLA S/O LATE MEHRUNBI AGED ABOUT 40 YEARS, R/AT NO. -

Prabhavathi Elegant

https://www.propertywala.com/prabhavathi-elegant-bangalore Prabhavathi Elegant - Whitefield, Bangalore Apartment for sale in White field 1, 2, 3 BHK near ashram road Prabhavathi Elegant is luxurious project of Prabhavathi Developers, offering you 1/2/3 BHK Residential apartments and located at Whitefield, Bangalore. Project ID : J781190017 Builder: Prabhavathi Properties: Apartments / Flats, Independent Houses Location: Prabhavathi Elegant,Kadugodi, Whitefield, Bangalore - 560037 (Karnataka) Completion Date: Jan, 2015 Status: Started Description Prabhavathi Elegant is available on peaceful, posh, and pollution free surrounding of Whitefield, Bangalore. It offers you 1/2/3 BHK Residential apartments with all aspect modern amenities features like well-equipped gym, covered car parking, automatic lift, swimming pool etc. The project having 60% of the total land as open space, this open space will provide you fresher air to the residents. Many significant area and prime location is very close to from the project where you can easily access the city for your daily needs. Type - 1/2/3 BHK Apartments Sizes - 970 - 1200 Sq. Ft. Price - On Request Amenities Automatic Lift Swimming Pool Party Hall Covered Car Parking Well Equipped Gym Prabhavathi Builders and Developers Pvt. Ltd. made its debut in 2007 under the leadership of Mr. BE Praveen Kumar, who is founder of Managing director. I have proud in announcing that we are today one of the fastest growing realtors in Bangalore with our primary focused being on Residential apartments. We have been credited with over 25 completed projects in Bangalore, Prabhavathi Bliss I, Prabhavathi Plasma, Prabhavathi Rishab, Prabhavathi Woods, Prabhavathi Meridian are a few names which are now given possession to its buyer. -

Venue Details 12Th Step Corporation

Venue Details Venue Details Venue Details 12th Step - BEL Group - Ever Growing - Corporation Sports Club 95352 67966, 080 22340444 BEL Fine Arts Complex 90352 15403, 99800 50798 SFS School, Near Vimalaya Hospital 99452 63934, 99869 78686 4th Square - Jalahalli Eng, Kan, Tam Hosur Main Road - Austin Town Sun 10.00 am, Mon 10.00 am Bangalore 560 013 Mon 7.00 pm, Tue 7.00 pm, Thu Huskar Gate Stop Tue 7.00 pm, Fri 7.00 pm Acceptance - 7.00 pm, Fri 7.00 pm, Sun 11:00 Electronic City Nammura Sarkari Madari Pratamika Shale 90367 33061, 90352 15403 am Evergreen Prabhakar Jalahalli Village - Bembala - Taluk Office Compound 9344865860 Bangalore 560 013 Sat 7.00 pm Dr.Ambedkar Sena Samithi 70933 63621, 98863 70082 Hosur Kan, Tam Action - Near K.R.Puram Railway Station - Mon 7.00 pm CSI Church, CSI Colony, Kothnur Post 81974 88144, 78997 04143 Vijinapura Tue 7.00 pm, Sat 7.00 pm First Step - Kothnur - Carmel Convent Elumalai St Francis School, Opp. Krupanidhi 99869 78686, 080 22340444 Bangalore 560077 Thu 7.00 pm, Sat 11.00 am Near Sagar Apollo Hospital 81236 18438 College Eng Adaikalam - Tilak Nagar Kan, Tam Sarjapur Road Fri 7.00 pm Government School 95352 67966, 080 22340444 Jayanagar Mon, Fri, Sat 7.00pm Koramangala Near Anjaneya Temple And Passport - Chandrodaya - Fourth Dimension - Office Mon 7.00 pm, Wed 7.00 p.m, Fri Chandra High School 82962 88230, 080 2234 0444 Jyothi School 89044 17280, 080 22340444 Koramangala 7.00 pm, Sat 7.00 pm Prakash Nagar Kan, Tam Hennur Bagalur Main Road - Anbillam - Rajajinagar Mon 7.00 pm, Sat 7.00 pm, Sun Lingarajapuram Mon 6.30 pm, Wed 6.30 pm, Gospel Street 89044 17280, 88615 73981 7.00 pm Thu 6.30 pm, Sat 6.30 pm, Sun Old Bagalur Layout Kan, Tam Chetana - 6.30 pm Lingarajpuram Mon 7.00 pm, Thu 7.00 pm St. -

CLIMATRANS Case City Report Bengaluru

CLIMATRANS Case City Presentation Bengaluru Dr. Ashish Verma Assistant Professor Transportation Engineering Dept. of Civil Engg. and CiSTUP Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bangalore, India [email protected] 1 PARTNERS : 2 Key Insights 7th most urbanized State Bangalore is the Capital 5th largest metropolitan city in India in terms of population ‘ Silicon Valley ’ of India District Population: 96, 21,551 District area: 2196 sq. km Density: 6,851 persons/Sq.km City added about 2 million people in just last decade Most urbanized district with 90.94% in Urban areas Figure.1: Bangalore Map Mobility: 4 Long travel times Peak hour travel speed in the city is 17 km/hr Poor road safety, inadequate infrastructure and environmental pollution Over 0.4million new vehicles were registered between 2013 and 2014 Public transport in suburban areas has not developed in pace with urban expansion. Fig.2: Peak hour traffic at Commercial Street Household Growth Households 2377056 5 2500000 2000000 1500000 1278333 859188 1000000 549627 500000 0 1981 1991 2001 2011 Households Area 7 City 1 Town Karnataka State Municipal Municipal Government Notification, Council’s Council January 2007 100 wards of Bangalore 111 villages Mahanagara Around City Palike Bruhat Bangalore Mahanagara Palike 7 Total Metropolitan Urban Surface Area Urban Surface Area (sq.km) 1400 700 1241 741 0 2007 2011 Urban Expansion 8 Figure.4: Map showing urban expansion of Bangalore Economy 9 Initially driven by Public Sector Undertakings and the textile industry. Shifted to high-technology service industries in the last decade. Bangalore Urban District contributes 33.8% to GSDP at Current Prices. -

An Empirical Study of Urban Infrastructure in Bengaluru

International Journal of Applied Research 2016; 2(7): 559-562 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 5.2 An empirical study of urban infrastructure in IJAR 2016; 2(7): 559-562 www.allresearchjournal.com Bengaluru Received: 01-05-2016 Accepted: 19-06-2016 Mallikarjun Chanmal and Uma TG. Mallikarjun Chanmal Associate Professor and HOD of Commerce, HKES’s Sree Abstract Veerendra Patil Degree There is a strong positive link between national levels of human development and urbanization levels, College, Sadashiva Nagar, while cities spearhead their countries’ economic development, transforming society through Bengaluru-560 080 extraordinary growth in the productivity of labour and promising to liberate the masses from poverty, hunger, disease and premature death. However, the implications of rapid urban growth include Uma TG. increasing unemployment, lack of urban services, overburdening of existing infrastructure and lack of Assistant Professor, access to land, finance and adequate shelter, increasing violent crime and sexually transmitted diseases, Department of Commerce and and environmental degradation. Even as national output is rising, a decline in the quality of life for a Management, Maharani majority of population that offsets the benefit of national economic growth is often witnessed. Women’s Arts, Commerce and Urbanization thus imposes significant burden to sustainable development. Management College, Seshadri Road, Bengaluru-560 001 Keywords: Urban infrastructure, Health, Economic Growth, Waste Collection, Urbanization -

Urban Water Supply: Contestations and Sustainability Issues in Greater Bangalore

Journal of Politics & Governance, Vol. 3, No. 4, October-December 2014 Urban Water Supply: Contestations and Sustainability Issues in Greater Bangalore Srihari Hulikal Muralidhar Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Chennai Abstract The move towards privatization of public utilities such as water sector in India, particularly in the metropolitan areas, has gone hand in hand with the growing gap between demand and supply of water. With fiscal discipline being the key mantra of successive governments, cost recovery as a policy goal is prioritized over access to water and sanitation. This paper is a critical assessment of Greater Bangalore Water and Sanitation Project (GBWASP), which aims to provide piped water to more than twenty lakh residents in Greater Bangalore. The implementation of the Karnataka Groundwater Act, 2011, and the debates around it are also examined in detail. The four main arguments are: huge gap between rhetoric and ground realities when it comes to the implementation of GBWASP and the Groundwater Act; the contestations between the elected representatives and bureaucrats have implications for urban governance; the axes of dispute between the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board and citizens have changed over time; the politics of negotiating access to water also bring questions of sustainability to the fore. Keywords: Borewell, Privatization, Water [This paper was presented at the 2nd National Conference on Politics & Governance, NCPG 2014 held at India International Centre Annexe, New Delhi on 3 August 2014] Introduction The Greater Bangalore Water and Sanitation Project (GBWASP) was launched in 2003 in Bangalore and is implemented by the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB). -

Registered Office Address: Mindtree Ltd, Global Village, RVCE Post, Mysore Road, Bengaluru-560059, Karnataka, India

Registered Office Address: Mindtree Ltd, Global Village, RVCE Post, Mysore Road, Bengaluru-560059, Karnataka, India. CIN: L72200KA1999PLC025564 E-mail: [email protected] Ref: MT/STAT/CS/20-21/02 April 14, 2020 BSE Limited National Stock Exchange of India Limited Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers, Exchange Plaza, Bandra Kurla Complex, Dalal Street, Mumbai 400 001 Bandra East, Mumbai 400 051 BSE: fax : 022 2272 3121/2041/ 61 NSE : fax: 022 2659 8237 / 38 Phone: 022-22721233/4 Phone: (022) 2659 8235 / 36 email: [email protected] email : [email protected] Dear Sirs, Sub: Reconciliation of Share Capital Audit Report for the quarter ended March 31, 2020 Kindly find enclosed the Reconciliation of Share Capital Audit Certificate for the quarter ended March 31, 2020 issued by Practicing Company Secretary under Regulation 76 of the SEBI (Depositories and Participants) Regulations, 2018. Please take the above intimation on records. Thanking you, Yours sincerely, for Mindtree Limited Vedavalli S Company Secretary Mindtree Ltd Global Village RVCE Post, Mysore Road Bengaluru – 560059 T +9180 6706 4000 F +9180 6706 4100 W: www.mindtree.com · G.SHANKER PRASAD ACS ACMA PRACTISING COMPANY SECRETARY # 10, AG’s Colony, Anandnagar, Bangalore-560 024, Tel: 42146796 e-mail: [email protected] RECONCILIATION OF SHARE CAPITAL AUDIT REPORT (As per Regulation 76 of SEBI (Depositories & Participants) Regulations, 2018) 1 For the Quarter Ended March 31, 2020 2 ISIN INE018I01017 3 Face Value per Share Rs.10/- 4 Name of the Company MINDTREE LIMITED 5 Registered Office Address Global Village, RVCE Post, Mysore Road, Bengaluru – 560 059. 6 Correspondence Address Global Village, RVCE Post, Mysore Road, Bengaluru – 560 059. -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR6645 Implementation Status & Results India Karnataka Municipal Reform Project (P079675) Operation Name: Karnataka Municipal Reform Project (P079675) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 14 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 17-Dec-2011 Country: India Approval FY: 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: SOUTH ASIA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Karnataka Urban Infrastructure Development Finance Corporation Key Dates Board Approval Date 14-Mar-2006 Original Closing Date 30-Apr-2012 Planned Mid Term Review Date 23-Feb-2009 Last Archived ISR Date 17-Dec-2011 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 30-Jun-2006 Revised Closing Date 31-Mar-2014 Actual Mid Term Review Date 15-Apr-2009 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The project objective is to help improve the delivery of urban services through enhancing the quality of urban infrastrucuture, and strengthening the institutional and financial frameworks for urban services at the ULB and state levels. Key objectives include: - Strengthen institutional and financial frameworks in urban service delivery at ULB and state. - Improve the qhality of infrastructure and mobilize financial resources in participating ULBs - Improve roads system in Bangalore and the sanitary conditions of the population in eight ULBs surrounding Bangalore city, while ensuring financial viability and sustainability Has the Project Development Objective been changed since -

Alumni Association of MS Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences

Alumni Association of M.S. Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences (SAMPARK), Bangalore M.S. Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences Department of Automotive & Aeronautical Engineering Program Year of Name Contact Address Photograph E-mail & Mobile Sl NO Completed Admiss ion # 25 Biligiri, 13th cross, 10th A Main, 2nd M T Layout, [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive 574 2013 Pramod M Malleshwaram, Bangalore- 9916040325 Engineering) 560003 S/o L. Srinivas Rao, Sai [email protected] Dham, D-No -B-43, Near M. Sc. (Automotive m 573 2013 Lanka Vinay Rao Torwapool, Bilaspur (C.G)- Engineering) 9424148279 495001 9406114609 3-17-16, Ravikunj, Parwana Nagar, [email protected] Upendra M. Sc. (Automotive Khandeshwari road, Bank m 572 2013 Padmakar Engineering) colony, 7411330707 Kulkarni Dist - BEED, State – 8149705281 Maharastra No.33, 9th Cross street, Dr. Radha Krishna Nagar, [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Venkata Krishna Teachers colony, 571 2013 0413-2292660 Engineering) S Moolakulam, Puducherry-605010 # 134, 1st Main, Ist A cross central Excise Layout [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Bhoopasandra RMV Iind 570 2013 Anudeep K N om Engineering) stage, 9686183918 Bengaluru-560094 58/F, 60/2,Municipal BLDG, G. D> Ambekar RD. Parel [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Tekavde Nitin 569 2013 Bhoiwada Mumbai, om Engineering) Shivaji Maharashtra-400012 9821184489 Thiyyakkandiyil (H), [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Nanminda (P.O), Kozhikode / 568 2013 Sreedeep T K m Engineering) Kerala – 673613 4952855366 #108/1, 9th Cross, themightyone.lohith@ M. Sc. (Automotive Lakshmipuram, Halasuru, 567 2013 Lohith N gmail.com Engineering) Bangalore-560008 9008022712 / 23712 5-8-128, K P Reddy Estates,Flat No.A4, indu.vanamala@gmail. -

MAP:Bengaluru Rural and Urban Districts

77°10'0"E 77°20'0"E 77°30'0"E 77°40'0"E 77°50'0"E 78°0'0"E ra Alipu BENGALURU RURAL AND URBAN DISTRICTS GEOGRAPHICAL AREA wards 13°30'0"N To i (KARNATAKA) av eb d n o T s d 4 r 9 a w H CHIKKABALLAPURA o S T KEY MAP CHIKKABALLAPURA CA-02 CA-03 r TUMKUR u p ± a l CA-01 l a b a CA-04 KOLAR i k CA-06 k d i n h a C s CA-05 s N d r d r a a w w o CA-07 o T T S e H T ger CA-08 o Urdi 9 w ds RAMANAGARA a ar r w d To NH-07 s K ¤£ KRISHNAGIRI CA-02 13°20'0"N o r a 13°20'0"N 4 ta H 7 g S er KODIHALLI LAKE u Total Population within the Geographical Area as per Census 2011 e r VIJAYAPURA POND u T k 106.12 Lacs (Approx.) o VIJAYAPURA (TMC) e a DARGAJOGIHALLI (CT) et z wa p i ¤£ sa NH- DOD BALLAPUR .! Ho r ds r Va d .! wa Total Geographical Area (Sq KMs) No. of Charge Areas s T 20 /" 7 To 0 S s 2 a 7 t - H t d u a r 4395 8 NH 1 m £ 0 96 gh a ¤ 4 k SH la w u id o r S T 7 0 s CA-03 2 d - r Charge Area Identification Taluka Name H a N £¤ DEVANAHALLI w /" To CA-01 Nelamangala -04 H ¤£N N H - CA-02 Dod Ballapur £¤ 2 0 3 7 9 TUMKUR H H S S CA-03 Devanahalli CA-04 Hosakote MADHURE KERE LAKE 07 CA-05 Bangalore East -2 THYAMAGONDLU H *# N£¤ CA-06 Bangalore North CA-07 Bangalore South SULIBELE S ¤£N H *# H - CA-08 Anekal alli 7 0 Areh 4 7 ards Tow CA-01 KADIGENAHALLI (CT) 13°10'0"N HESSARGHATTA LAKE S .! H 7 LEGEND 13°10'0"N 4 4 HUNASAMARANAHALLI (CT) *# BUDIGERE NH-0£¤ .! BAGALUR *# HESARAGHATTA r LANDMARKS *# rds Kola SH 104 owa 2 T 8 H 5 S 07 3 NH-2 H /" TALUKA HEAD QUARTER YELAHANKA (CMC) £¤ S NELAMANGALA .! ¤£N H SH - 74 SH 0 .! MAJOR TOWNS /" 4 3 CA-04 9 -

Bommanahalli, 1352 I LARGE GREEN G-96 Wire Drawing C1 NA NA NA Both NA NA NA NA CLOSED NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA Yes NA NA NA AEO-1 South Urban Bangalore - 560068

F-REGISTER For the Period upto 31.03.2021- Regional Office-Bommanhalli AIR POLLUTION CONTROL STATUS Closed by the Board Consent/ WATER POLLUTION CONTROL STATUS (INDICATE Categor Applicability of Acts (A/W/B) (INDICATE AS "Y" IN THE RELEVANT under authorisation AS "Y" IN THE RELEVANT COLUMN) y COLUMN) Year of Type of Activity as Manufacturing Operationa validty period Sl Capital EIS/No BWM ETP APC APC APC UIN PCB ID Esatblis Name & Address of the Organizations Organizati Size Color per Board Activity /Waste l status HWM Plastic e-waste MSW Remarks ETP/STP No Investment n UNDER ETP UNDER CONNEC SYSTEM SYSTEM SYSTEM hment on Notification Disposal O/Y/C HWM UNDER DEFAU EIA/17 WA AA EPA Consent BMW PLASTIC E-Waste MSW Consent CONST PLANNING TED TO UNDER UNDER UNDER OPERATI Defaulters LTERS Cat RUCTI STAGE UGD OPERATI CONSTR PLANNI ON ON ON UCTION NG 3M India Limited, No.48-51, Electronic City, Bangalore Bangalore 1 0304016209 10781 50490 I LARGE RED 1182 R&D O NA NA NA Both Y Y NA Y 30.06.2021 30.06.2022 Life Time NA 30.06.17 NA NA NA Yes NA Yes NA NA NA AEO-2 Hosur Road, Bangalore-100. South Urban S.K.F. Technologies India Pvt Ltd., No.13/5, Bangalore Bangalore 2 0304016210 Singasnadra, 13th KM, Hosur Road, 4017 I LARGE RED R-83 Elastomeric Seals C1 NA NA NA Both Y NA NA NA CLOSED NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA AEO-2 South Urban Bangalore-68. -

Central Administrative Tribunal Bangalore Bench, Bangalore

1 RA.No.119/2016/CAT/Bangalore Bench CENTRAL ADMINISTRATIVE TRIBUNAL BANGALORE BENCH, BANGALORE REVIEW APPLICATION NO. 170/00119/2016 IN OA. NO. 170/00126 TO 00153/2016 DATED THIS THE 26TH DAY OF JULY, 2017 HON'BLE DR. K.B. SURESH, MEMBER(J) HON'BLE SHRI P.K. PRADHAN, MEMBER(A) 1.Sri Suresh K.D., S/o Sri Late Damodharan K.G., Aged about 55 years, R/a No. D-203, K.K.R-A.M.R. Apartment, H.M.T. Factory Main Road, Jalahalli, Bangalore-560 013. 2.Smt Mary Kumari Louis, D/o Sri Kannan.C, Aged about 54 years, R/a “Shalom”, #59, 6th Cross Verma Layout, Bhuvaneshwari Nagar, Hebbal Kempapna, Bangalore-560 024. 3.Smt Nirmala.R., D/o Sri Rajendran V.T., Aged about 47 years, R/at No.168, 2nd 'B' Main, Talakaveri Layout, Amruthahalli, Bangalore-560 092. 4.Sri Vijayakumar.K., S/o Sri Balakrishnan Nair P.V., Aged about 52 years, R/a #933, 4th Cross, 7th Main, 5th Block, BEL Layout, Bangalore-560 097. 5.Smt Vijaya Sunanda.M., D/o Sri Sharma M.R., Aged about 51 years, R/a #4, 2nd Main, 1st Cross, J.P. Nagar, 3rd Phase, 9th Block Eastend, Bangalore-560 078. 2 RA.No.119/2016/CAT/Bangalore Bench 6.Smt Sheetal Chaya S., D/o Sri Satyadev Rao K.S., Aged about 46, R/a #17, 1st Floor, “Nikhil” SBI Colony II Phase, Devarachikkanahalli, Bangalore-560 076. 7.Smt Gayathri Devi P.R., D/o Sri Ramanna P., Aged about 49 years, R/a 1393, 9th 'E' Cross, J.P.