The Puzzle of the Ice Age Americans (Adapted from the 2002 Submarine Ring of Fire Expedition)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution of Freshwater Midges in Relation to Air Temperature and Lake Depth

J Paleolimnol (2006) 36:295-314 DOl 1O.1007/s10933-006-0014-6 A northwest North American training set: distribution of freshwater midges in relation to air temperature and lake depth Erin M. Barley' Ian R. Walker' Joshua Kurek, Les C. Cwynar' Rolf W. Mathewes • Konrad Gajewski' Bruce P. Finney Received: 20 July 2005 I Accepted: 5 March 2006/Published online: 26 August 2006 © Springer Science+Business Media B.Y. 2006 Abstract Freshwater midges, consisting of Chiro- organic carbon, lichen woodland vegetation and sur- nomidae, Chaoboridae and Ceratopogonidae, were face area contributed significantly to explaining assessed as a biological proxy for palaeoclimate in midge distribution. Weighted averaging partial least eastern Beringia. The northwest North American squares (WA-PLS) was used to develop midge training set consists of midge assemblages and data inference models for mean July air temperature 2 for 17 environmental variables collected from 145 (R boot = 0.818, RMSEP = 1.46°C), and transformed 2 lakes in Alaska, British Columbia, Yukon, Northwest depth (1n (x+ l); R boot = 0.38, and RMSEP = 0.58). Territories, and the Canadian Arctic Islands. Canon- ical correspondence analyses (CCA) revealed that Key words Chironomidae : Transfer function . mean July air temperature, lake depth, arctic tundra Beringia' Air temperature . Lake depth' Canonical vegetation, alpine tundra vegetation, pH, dissolved correspondence analysis . Paleoclimate E. M. Barley· R. W. Mathewes Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada V5A IS6 Introduction I. R. Walker Departments of Biology, and Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of British Columbia Okanagan, Palaeoecologists seeking to quantify past environ- Kelowna, BC, Canada VIV IV7 mental changes rely increasingly on transfer func- e-mail: [email protected] tions that make use of biological proxies (Battarbee J. -

Post-Glacial Flooding of the Bering Land Bridge Dated to 11 Cal Ka BP Based on New Geophysical and Sediment Records

Clim. Past, 13, 991–1005, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-13-991-2017 © Author(s) 2017. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Post-glacial flooding of the Bering Land Bridge dated to 11 cal ka BP based on new geophysical and sediment records Martin Jakobsson1, Christof Pearce1,2, Thomas M. Cronin3, Jan Backman1, Leif G. Anderson4, Natalia Barrientos1, Göran Björk4, Helen Coxall1, Agatha de Boer1, Larry A. Mayer5, Carl-Magnus Mörth1, Johan Nilsson6, Jayne E. Rattray1, Christian Stranne1,5, Igor Semiletov7,8, and Matt O’Regan1 1Department of Geological Sciences and Bolin Centre for Climate Research, Stockholm University, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden 2Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark 3US Geological Survey MS926A, Reston, Virginia 20192, USA 4Department of Marine Sciences, University of Gothenburg, 412 96 Gothenburg, Sweden 5Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire 03824, USA 6Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 7Pacific Oceanological Institute, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 690041 Vladivostok, Russia 8Tomsk Polytechnic University, Tomsk, Russia Correspondence to: Martin Jakobsson ([email protected]) Received: 26 January 2017 – Discussion started: 13 February 2017 Accepted: 1 July 2017 – Published: 1 August 2017 Abstract. The Bering Strait connects the Arctic and Pacific Strait and the submergence of the large Bering Land Bridge. oceans and separates the North American and Asian land- Although the precise rates of sea level rise cannot be quanti- masses. The presently shallow ( ∼ 53 m) strait was exposed fied, our new results suggest that the late deglacial sea level during the sea level lowstand of the last glacial period, which rise was rapid and occurred after the end of the Younger permitted human migration across a land bridge today re- Dryas stadial. -

The Archaeology of Beringia

The Archaeology ofBeringia FREDERICK HADLEIGH WEST Columbia University 'Press New York, 1981 ARLIS Alaska Resources Library & Information Services Library Building, Suite 111 .3211 Providence Drive Anchorage, AK 99508·4614 This document is copyrighted material. Alaska Resources Library and Information Services (ARLIS) is providing this excerpt in an attempt to identify and post all documents from the Susitna Hydroelectric Project. This book is identified as APA no. 2316 in the Susitna Hydroelectric Project Document Index (1988), compiled by the Alaska Power Authority. It is unable to be posted online in its entirety. Selected pages are displayed here to identify the published work. The book is available at call number F951.W5 1981 in the ARLIS Susitna collection. Contents Figures Vll Tables IX Preface Xl Acknowledgments XVll Introduction 1 l. Northeastern Siberia and Alaska: The Remnants of Beringia as They Exist Today 5 2. Reconstructing the Environment of Late Pleistocene Beringia 31 3. Archaeology: The Beringians 75 4. Origin and Relationships of the Eastern Branch of the Beringian Tradition 155 5. The Beringian Tradition and the Origin of New World Cultures 183 6. Epilogue: The Beringians and Beyond 211 References 233 Author Index 255 Subject Index 259 Figures Frontispiece Beringia at Wiirm maximum. 1. Climates of northeast Asia and northwest America. 13 2. Vegetation associations, northeast Asia and northwest America. 15 3. Native languages, northeast Asia and northwest America. 30 4. Local vegetational successions in the late Quaternary summarized from pollen studies. 36 5. Generalized regional vegetational successions in western Beringia. 47 6. Summarized vegetation successions at archaeological localities in western Beringia. -

Archaeology Resources

Archaeology Resources Page Intentionally Left Blank Archaeological Resources Background Archaeological Resources are defined as “any prehistoric or historic district, site, building, structure, or object [including shipwrecks]…Such term includes artifacts, records, and remains which are related to such a district, site, building, structure, or object” (National Historic Preservation Act, Sec. 301 (5) as amended, 16 USC 470w(5)). Archaeological resources are either historic or prehistoric and generally include properties that are 50 years old or older and are any of the following: • Associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history • Associated with the lives of persons significant in the past • Embody the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction • Represent the work of a master • Possess high artistic values • Present a significant and distinguishable entity whose components may lack individual distinction • Have yielded, or may be likely to yield, information important in history These resources represent the material culture of past generations of a region’s prehistoric and historic inhabitants, and are basic to our understanding of the knowledge, beliefs, art, customs, property systems, and other aspects of the nonmaterial culture. Further, they are subject to National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) review if they are historic properties, meaning those that are on, or eligible for placement on, the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). These sites are referred to as historic properties. Section 106 requires agencies to make a reasonable and good faith efforts to identify historic properties. Archaeological resources may be found in the Proposed Project Area both offshore and onshore. -

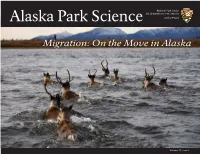

Migration: on the Move in Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Migration: On the Move in Alaska Volume 17, Issue 1 Alaska Park Science Volume 17, Issue 1 June 2018 Editorial Board: Leigh Welling Jim Lawler Jason J. Taylor Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Guest Editor: Laura Phillips Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Contributing Editor: Stacia Backensto Design: Nina Chambers Contact Alaska Park Science at: [email protected] Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Migration: On the Move in Alaska ...............1 Future Challenges for Salmon and the Statewide Movements of Non-territorial Freshwater Ecosystems of Southeast Alaska Golden Eagles in Alaska During the A Survey of Human Migration in Alaska's .......................................................................41 Breeding Season: Information for National Parks through Time .......................5 Developing Effective Conservation Plans ..65 History, Purpose, and Status of Caribou Duck-billed Dinosaurs (Hadrosauridae), Movements in Northwest -

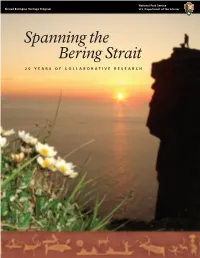

Spanning the Bering Strait

National Park service shared beringian heritage Program U.s. Department of the interior Spanning the Bering Strait 20 years of collaborative research s U b s i s t e N c e h UN t e r i N c h UK o t K a , r U s s i a i N t r o DU c t i o N cean Arctic O N O R T H E L A Chu a e S T kchi Se n R A LASKA a SIBERIA er U C h v u B R i k R S otk S a e i a P v I A en r e m in i n USA r y s M l u l g o a a S K S ew la c ard Peninsu r k t e e r Riv n a n z uko i i Y e t R i v e r ering Sea la B u s n i CANADA n e P la u a ns k ni t Pe a ka N h las c A lf of Alaska m u a G K W E 0 250 500 Pacific Ocean miles S USA The Shared Beringian Heritage Program has been fortunate enough to have had a sustained source of funds to support 3 community based projects and research since its creation in 1991. Presidents George H.W. Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev expanded their cooperation in the field of environmental protection and the study of global change to create the Shared Beringian Heritage Program. -

Radar Observations of Arctic Bird Migration in the Beringia Region A

ARCTIC VOL. 62, NO. 1 (MARCH 2009) P. 25–37 Radar Observations of Arctic Bird Migration in the Beringia Region A. HEDENSTRÖM,1 T. ALERSTam,2 J. BÄCKmaN,2 G.A. GUDMUNDSSON,3 S. HENNINGSSON,2 H. KarLSSON,2 M. ROSÉN2 and R. STraNDBErg2 (Received 17 August 2007; accepted in revised form 17 April 2008) ABSTRACT. Bird migration was recorded by tracking radar and visual observations in the Beringia region. The data were subdivided into seven areas extending from north of Wrangel Island southeastward toward the Bering Strait and then northwestward off the coast of Alaska to Point Barrow. The studies, which took place during a ship-based expedition between 30 July and 19 August 2005, recorded a total of 557 tracks (average duration 120 seconds) of bird flocks or individuals on post-breeding migration. The dominant eastward-flying flocks were likely composed of shorebirds on their way from breeding areas in central or eastern Siberia to intermediate stopovers and final destinations inN orth and South America. The courses were more southerly into the Bering Strait, possibly because of topographical influence. At two areas, the Chukchi Sea and Koluch- inskaya Bay, there was also a westward component of migrants. At the Chukchi Sea these were almost certainly passerine birds migrating from Alaska to wintering areas in Asia and Africa, while at Koluchinskaya Bay, king eiders on molt migration could represent an important part of the westward component. The overall mean altitude of flights was 1157 m, and flight altitude was positively correlated with latitude. The mean ground speed was 15.9 m/s and the mean airspeed was 14.1 m/s, indicating that on average the birds were experiencing a small tail wind component. -

Historical Timeline for Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge

Historical Timeline Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge Much of the refuge has been protected as a national wildlife refuge for over a century, and we recognize that refuge lands are the ancestral homelands of Alaska Native people. Development of sophisticated tools and the abundance of coastal and marine wildlife have made it possible for people to thrive here for thousands of years. So many facets of Alaska’s history happened on the lands and waters of the Alaska Maritime Refuge that the Refuge seems like a time-capsule story of the state and the conservation of island wildlife: • Pre 1800s – The first people come to the islands, the Russian voyages of discovery, the beginnings of the fur trade, first rats and fox introduced to islands, Steller sea cow goes extinct. • 1800s – Whaling, America buys Alaska, growth of the fox fur industry, beginnings of the refuge. • 1900 to 1945 – Wildlife Refuge System is born and more land put in the refuge, wildlife protection increases through treaties and legislation, World War II rolls over the refuge, rats and foxes spread to more islands. The Aleutian Islands WWII National Monument designation recognizes some of these significant events and places. • 1945 to the present – Cold War bases built on refuge, nuclear bombs on Amchitka, refuge expands and protections increase, Aleutian goose brought back from near extinction, marine mammals in trouble. Refuge History - Pre - 1800 A World without People Volcanoes push up from the sea. Ocean levels fluctuate. Animals arrive and adapt to dynamic marine conditions as they find niches along the forming continent’s miles of coastline. -

Human Dispersal from Siberia to Beringia: Assessing a Beringian Standstill in Light of the Archaeological Evidence

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarWorks at Central Washington University Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Faculty Scholarship for the College of the Sciences College of the Sciences 12-2017 Human Dispersal from Siberia to Beringia: Assessing a Beringian Standstill in Light of the Archaeological Evidence Kelly E. Graf Ian Buvit Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/cotsfac Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, and the Genetics Commons Current Anthropology Volume 58, Supplement 17, December 2017 S583 Human Dispersal from Siberia to Beringia Assessing a Beringian Standstill in Light of the Archaeological Evidence by Kelly E. Graf and Ian Buvit With genetic studies showing unquestionable Asian origins of the first Americans, the Siberian and Beringian ar- chaeological records are absolutely critical for understanding the initial dispersal of modern humans in the Western Hemisphere. The genetics-based Beringian Standstill Model posits a three-stage dispersal process and necessitates several expectations of the archaeological record of northeastern Asia. Here we present an overview of the Siberian and Beringian Upper Paleolithic records and discuss them in the context of a Beringian Standstill. We report that not every expectation of the model is met with archaeological data at hand. The paleoanthropology of northeastern Asia and Alaska is and arid conditions during the LGM (e.g., Kuzmina and Sher paramount to understanding initial human dispersal in the 2006; Szpak et al. 2010). Here we consider the archaeological Western Hemisphere because of their Late Pleistocene con- records of Siberia and Beringia in the context of the Beringian nection by the Bering Land Bridge, the now submerged con- Standstill Model (BSM), a hypothesis proposed by geneticists tinental shelf below the Bering Strait between far northeastern to explain late Pleistocene dispersal of modern humans from Russia and western Alaska. -

Beringia Vocabulary

Beringia Vocabulary 1) artifact--an object made by humans, such as a tool The term Beringia refers to the 1,000-mile long landmass th2a) t acrocnhnaecotloegdy A--sthiae astnudd yN oofr thhis Atomrice raicnad 1pr0e,h0i0s0to-r2ic5 ,000 years ago. Duringp tehoisp lteime, glaciers up to two miles thick covered large parts of North America, Europe and Asia. T3h)e ppaelerioondt owloagsy -c-athllee dst uthdey Pofl eeiasrtloyc leifen eb yIc loeo Akigneg. aSt ome very dry areas weforess iiclse-free during this time. Much of the Earth's water was locked up in the glaciers. Because of th4i)s psereah ilsetvoerilc d--rao pppeeridod s oigfn timficea bnetlfyo, ruep w troit t3e0n0 o fre et! Some areas that are now urencdoerrd weda theisr tboerycame dry land. The result was an intermittent land bridge stretching between 5) fossil--the remains, impression, imprint or bone of the two cao nlivtiinge nthtsin ugnder the present day Bering and Chukchi Seas. Scientists believe that Beringia was at its w6id) e esxtt ipnoctin--ta a sbpoeuctie 1s5 t,h0a0t 0h ayse adriesd a oguot., Anolt hloonuggehr icna lled a "bridge," the leaxnisdt ewnacse really a broad, grassy plain, which many animals stopped to feed on. 7) Pleistocene-- 2 million to 10,000 years ago Beringia The term Beringia refers to the 1,000-mile long landmass 1t0h,a0t0 c0o tnon 2e5c,t0e0d0 A yseiar asn adg No,o drtuhr inAgm teheri cpae r1io0d,0 k0n0o-w2n5 ,a0s0 0th e Pyleeaisrtso caegnoe. IDceu rAingge ,t hgilsa ctiiemrse ,u gpl atoc itewros mupile tso tthwicok mcoilveesr ethdi clakr ge pcaorvtse oref dN olartrhg eA mpaerrtisc ao, fE Nuorortphe ,A amned rAicsaia, Eaundro mpeu cahn odf Athseia e.a rth's wTahter pwearsio ldo cwkaeds ucpa lilne dth teh eg laPcleieirsst.o Tcheen es eIcae le Avegle d. -

The Bering Land Bridge: a Moisture Barrier to the Dispersal of Steppe–Tundra Biota?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Quaternary Science Reviews 27 (2008) 2473–2483 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev The Bering Land Bridge: a moisture barrier to the dispersal of steppe–tundra biota? Scott A. Elias*, Barnaby Crocker Geography Department, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK article info abstract Article history: The Bering Land Bridge (BLB) connected the two principal arctic biological refugia, Western and Eastern Received 14 April 2008 Beringia, during intervals of lowered sea level in the Pleistocene. Fossil evidence from lowland BLB Received in revised form 9 September 2008 organic deposits dating to the Last Glaciation indicates that this broad region was dominated by shrub Accepted 11 September 2008 tundra vegetation, and had a mesic climate. The dominant ecosystem in Western Beringia and the interior regions of Eastern Beringia was steppe–tundra, with herbaceous plant communities and arid climate. Although Western and Eastern Beringia shared many species in common during the Late Pleistocene, there were a number of species that were restricted to only one side of the BLB. Among the vertebrate fauna, the woolly rhinoceros was found only to the west of the BLB, North American camels, bonnet-horned musk-oxen and some horse species were found only to the east of the land bridge. These were all steppe–tundra inhabitants, adapted to grazing. The same phenomenon can be seen in the insect faunas of the Western and Eastern Beringia. -

Rare Vascular Plants of the North Slope a Review of the Taxonomy, Distribution, and Ecology of 31 Rare Plant Taxa That Occur in Alaska’S North Slope Region

BLM U. S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management BLM Alaska Technical Report 58 BLM/AK/GI-10/002+6518+F030 December 2009 Rare Vascular Plants of the North Slope A Review of the Taxonomy, Distribution, and Ecology of 31 Rare Plant Taxa That Occur in Alaska’s North Slope Region Helen Cortés-Burns, Matthew L. Carlson, Robert Lipkin, Lindsey Flagstad, and David Yokel Alaska The BLM Mission The Bureau of Land Management sustains the health, diversity and productivity of the Nation’s public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations. Cover Photo Drummond’s bluebells (Mertensii drummondii). © Jo Overholt. This and all other copyrighted material in this report used with permission. Author Helen Cortés-Burns is a botanist at the Alaska Natural Heritage Program (AKNHP) in Anchorage, Alaska. Matthew Carlson is the program botanist at AKNHP and an assistant professor in the Biological Sciences Department, University of Alaska Anchorage. Robert Lipkin worked as a botanist at AKNHP until 2009 and oversaw the botanical information in Alaska’s rare plant database (Biotics). Lindsey Flagstad is a research biologist at AKNHP. David Yokel is a wildlife biologist at the Bureau of Land Management’s Arctic Field Office in Fairbanks. Disclaimer The mention of trade names or commercial products in this report does not constitute endorsement or rec- ommendation for use by the federal government. Technical Reports Technical Reports issued by BLM-Alaska present results of research, studies, investigations, literature searches, testing, or similar endeavors on a variety of scientific and technical subjects. The results pre- sented are final, or a summation and analysis of data at an intermediate point in a long-term research project, and have received objective review by peers in the author’s field.