Lithic Technologies, Functional Variability, and Settlement Systems in Late Pleistocene Beringia – New Perspectives on a Colonization Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution of Freshwater Midges in Relation to Air Temperature and Lake Depth

J Paleolimnol (2006) 36:295-314 DOl 1O.1007/s10933-006-0014-6 A northwest North American training set: distribution of freshwater midges in relation to air temperature and lake depth Erin M. Barley' Ian R. Walker' Joshua Kurek, Les C. Cwynar' Rolf W. Mathewes • Konrad Gajewski' Bruce P. Finney Received: 20 July 2005 I Accepted: 5 March 2006/Published online: 26 August 2006 © Springer Science+Business Media B.Y. 2006 Abstract Freshwater midges, consisting of Chiro- organic carbon, lichen woodland vegetation and sur- nomidae, Chaoboridae and Ceratopogonidae, were face area contributed significantly to explaining assessed as a biological proxy for palaeoclimate in midge distribution. Weighted averaging partial least eastern Beringia. The northwest North American squares (WA-PLS) was used to develop midge training set consists of midge assemblages and data inference models for mean July air temperature 2 for 17 environmental variables collected from 145 (R boot = 0.818, RMSEP = 1.46°C), and transformed 2 lakes in Alaska, British Columbia, Yukon, Northwest depth (1n (x+ l); R boot = 0.38, and RMSEP = 0.58). Territories, and the Canadian Arctic Islands. Canon- ical correspondence analyses (CCA) revealed that Key words Chironomidae : Transfer function . mean July air temperature, lake depth, arctic tundra Beringia' Air temperature . Lake depth' Canonical vegetation, alpine tundra vegetation, pH, dissolved correspondence analysis . Paleoclimate E. M. Barley· R. W. Mathewes Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada V5A IS6 Introduction I. R. Walker Departments of Biology, and Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of British Columbia Okanagan, Palaeoecologists seeking to quantify past environ- Kelowna, BC, Canada VIV IV7 mental changes rely increasingly on transfer func- e-mail: [email protected] tions that make use of biological proxies (Battarbee J. -

Post-Glacial Flooding of the Bering Land Bridge Dated to 11 Cal Ka BP Based on New Geophysical and Sediment Records

Clim. Past, 13, 991–1005, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-13-991-2017 © Author(s) 2017. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Post-glacial flooding of the Bering Land Bridge dated to 11 cal ka BP based on new geophysical and sediment records Martin Jakobsson1, Christof Pearce1,2, Thomas M. Cronin3, Jan Backman1, Leif G. Anderson4, Natalia Barrientos1, Göran Björk4, Helen Coxall1, Agatha de Boer1, Larry A. Mayer5, Carl-Magnus Mörth1, Johan Nilsson6, Jayne E. Rattray1, Christian Stranne1,5, Igor Semiletov7,8, and Matt O’Regan1 1Department of Geological Sciences and Bolin Centre for Climate Research, Stockholm University, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden 2Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark 3US Geological Survey MS926A, Reston, Virginia 20192, USA 4Department of Marine Sciences, University of Gothenburg, 412 96 Gothenburg, Sweden 5Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire 03824, USA 6Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 7Pacific Oceanological Institute, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 690041 Vladivostok, Russia 8Tomsk Polytechnic University, Tomsk, Russia Correspondence to: Martin Jakobsson ([email protected]) Received: 26 January 2017 – Discussion started: 13 February 2017 Accepted: 1 July 2017 – Published: 1 August 2017 Abstract. The Bering Strait connects the Arctic and Pacific Strait and the submergence of the large Bering Land Bridge. oceans and separates the North American and Asian land- Although the precise rates of sea level rise cannot be quanti- masses. The presently shallow ( ∼ 53 m) strait was exposed fied, our new results suggest that the late deglacial sea level during the sea level lowstand of the last glacial period, which rise was rapid and occurred after the end of the Younger permitted human migration across a land bridge today re- Dryas stadial. -

UC Berkeley International Association of Obsidian Studies Bulletin

UC Berkeley International Association of Obsidian Studies Bulletin Title IAOS Bulletin 59 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3r35f908 Author Dillian, Carolyn D., [email protected] Publication Date 2018-06-15 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California IAOS International Association for Obsidian Studies Bulletin ISSN: 2310-5097 Number 59 Summer 2018 CONTENTS International Association for Obsidian Studies News and Information ………………………… 1 President Kyle Freund Notes from the President……....……….………. 2 Past President Rob Tykot MatLab for OHD Calculations…………………..9 Secretary-Treasurer Matt Boulanger Obsidian Macro-Core from Belize…………..…19 Bulletin Editor Carolyn Dillian Poverty Point’s Obsidian……………………….28 Webmaster Craig Skinner Instructions for Authors …..……………………42 About the IAOS………………………………...43 Web Site: http://members.peak.org/~obsidian/ Membership Application ………………………44 NEWS AND INFORMATION CONSIDER PUBLISHING IN THE NEWS AND NOTES IAOS BULLETIN Have news or announcements to share? The Bulletin is a twice-yearly publication that reaches Send them to [email protected] for a wide audience in the obsidian community. Please the next issue of the IAOS Bulletin. review your research notes and consider submitting an article, research update, news, or lab report for publication in the IAOS Bulletin. Articles and inquiries can be sent to [email protected] Thank you for your help and support! CALL FOR NOMINATIONS Kyle Freund has just begun his responsibilities as IAOS President, and Rob Tykot has stepped into the position of Past President for the coming year. That means that it’s now time for nominations for our next IAOS President. Elections will be held this winter and the winner announced at the 2019 IAOS meeting at the SAAs in Albuquerque. -

The Archaeology of Beringia

The Archaeology ofBeringia FREDERICK HADLEIGH WEST Columbia University 'Press New York, 1981 ARLIS Alaska Resources Library & Information Services Library Building, Suite 111 .3211 Providence Drive Anchorage, AK 99508·4614 This document is copyrighted material. Alaska Resources Library and Information Services (ARLIS) is providing this excerpt in an attempt to identify and post all documents from the Susitna Hydroelectric Project. This book is identified as APA no. 2316 in the Susitna Hydroelectric Project Document Index (1988), compiled by the Alaska Power Authority. It is unable to be posted online in its entirety. Selected pages are displayed here to identify the published work. The book is available at call number F951.W5 1981 in the ARLIS Susitna collection. Contents Figures Vll Tables IX Preface Xl Acknowledgments XVll Introduction 1 l. Northeastern Siberia and Alaska: The Remnants of Beringia as They Exist Today 5 2. Reconstructing the Environment of Late Pleistocene Beringia 31 3. Archaeology: The Beringians 75 4. Origin and Relationships of the Eastern Branch of the Beringian Tradition 155 5. The Beringian Tradition and the Origin of New World Cultures 183 6. Epilogue: The Beringians and Beyond 211 References 233 Author Index 255 Subject Index 259 Figures Frontispiece Beringia at Wiirm maximum. 1. Climates of northeast Asia and northwest America. 13 2. Vegetation associations, northeast Asia and northwest America. 15 3. Native languages, northeast Asia and northwest America. 30 4. Local vegetational successions in the late Quaternary summarized from pollen studies. 36 5. Generalized regional vegetational successions in western Beringia. 47 6. Summarized vegetation successions at archaeological localities in western Beringia. -

Oxford School of Archaeology: Annual Report 2012

OXFORD School of Archaeology Annual Report 2012–2013 THE SCHOOL OF ARCHAEOLOGY The School of Archaeology is one of the premier departments in the world for the study and teaching of the human past. Comprised primarily of the Institute of Archaeology and the Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, the School hosts a dynamic faculty, nearly one hundred undergraduates, and a large cohort of outstanding graduate students each year. It is one of the few places in the world where the many facets of archaeology come together to explore themes such as human origins and early hunter-gatherers, the ancient environment, classical and historical archaeology, and chronology. School of Archaeology 36 Beaumont Street, Oxford OX1 2PG www.arch.ox.ac.uk Reception +44(0)1865 278240 Helena Hamerow (Head of School) [email protected] Lidia Lozano (Administrator) [email protected] Barbara Morris (Graduate Administrator) [email protected] Lynda Smithson (Academic Secretary) [email protected] Jeremy Worth (ICT Manager) [email protected] Stephen Hick (Finance Officer) [email protected] Institute of Archaeology 36 Beaumont Street, Oxford OX1 2PG www.arch.ox.ac.uk/institute Reception +44(0)1865 278240 Chris Gosden (Director) [email protected] Lidia Lozano (Administrator) [email protected] Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art Dyson Perrins Building, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3QY www.rlaha.ox.ac.uk Reception +44(0)1865 285222 Mark Pollard (Director) [email protected] Diane Baker (Administrator) [email protected] Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit Dyson Perrins Building, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3QY http://c14.arch.ox.ac.uk Reception +44(0)1865 285229 Christopher Ramsey (Director) [email protected] Cover photo: A hand axe found close to Dar es-Soltan, Rabat, Morocco, photographed using RTI imaging for the Morocco Caves Project: http://www.arch.ox.ac.uk/MCP.html Ian R. -

Archaeology Resources

Archaeology Resources Page Intentionally Left Blank Archaeological Resources Background Archaeological Resources are defined as “any prehistoric or historic district, site, building, structure, or object [including shipwrecks]…Such term includes artifacts, records, and remains which are related to such a district, site, building, structure, or object” (National Historic Preservation Act, Sec. 301 (5) as amended, 16 USC 470w(5)). Archaeological resources are either historic or prehistoric and generally include properties that are 50 years old or older and are any of the following: • Associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history • Associated with the lives of persons significant in the past • Embody the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction • Represent the work of a master • Possess high artistic values • Present a significant and distinguishable entity whose components may lack individual distinction • Have yielded, or may be likely to yield, information important in history These resources represent the material culture of past generations of a region’s prehistoric and historic inhabitants, and are basic to our understanding of the knowledge, beliefs, art, customs, property systems, and other aspects of the nonmaterial culture. Further, they are subject to National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) review if they are historic properties, meaning those that are on, or eligible for placement on, the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). These sites are referred to as historic properties. Section 106 requires agencies to make a reasonable and good faith efforts to identify historic properties. Archaeological resources may be found in the Proposed Project Area both offshore and onshore. -

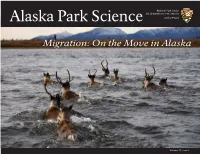

Migration: on the Move in Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Migration: On the Move in Alaska Volume 17, Issue 1 Alaska Park Science Volume 17, Issue 1 June 2018 Editorial Board: Leigh Welling Jim Lawler Jason J. Taylor Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Guest Editor: Laura Phillips Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Contributing Editor: Stacia Backensto Design: Nina Chambers Contact Alaska Park Science at: [email protected] Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Migration: On the Move in Alaska ...............1 Future Challenges for Salmon and the Statewide Movements of Non-territorial Freshwater Ecosystems of Southeast Alaska Golden Eagles in Alaska During the A Survey of Human Migration in Alaska's .......................................................................41 Breeding Season: Information for National Parks through Time .......................5 Developing Effective Conservation Plans ..65 History, Purpose, and Status of Caribou Duck-billed Dinosaurs (Hadrosauridae), Movements in Northwest -

The Global History of Paleopathology

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/31/12, NEWGEN TH E GLOBA L H ISTORY OF PALEOPATHOLOGY 000_JaneBuikstra_FM.indd0_JaneBuikstra_FM.indd i 11/31/2012/31/2012 44:03:58:03:58 PPMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/31/12, NEWGEN 000_JaneBuikstra_FM.indd0_JaneBuikstra_FM.indd iiii 11/31/2012/31/2012 44:03:59:03:59 PPMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/31/12, NEWGEN TH E GLOBA L H ISTORY OF PALEOPATHOLOGY Pioneers and Prospects EDITED BY JANE E. BUIKSTRA AND CHARLOTTE A. ROBERTS 3 000_JaneBuikstra_FM.indd0_JaneBuikstra_FM.indd iiiiii 11/31/2012/31/2012 44:03:59:03:59 PPMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/31/12, NEWGEN 1 Oxford University Press Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With o! ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland " ailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © #$%# by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. %&' Madison Avenue, New York, New York %$$%( www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. CIP to come ISBN-%): ISBN $–%&- % ) * + & ' ( , # Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 000_JaneBuikstra_FM.indd0_JaneBuikstra_FM.indd iivv 11/31/2012/31/2012 44:03:59:03:59 PPMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/31/12, NEWGEN To J. -

Lithic Technological Organization, Mobility, and Landscape Use from Jakes Valley, Nevada

University of Nevada, Reno Paleoindian Occupations in the Great Basin: A Comparative Study of Lithic Technological Organization, Mobility, and Landscape Use from Jakes Valley, Nevada A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Mark B. Estes Dr. Gary Haynes/Thesis Advisor May, 2009 Copyright by Mark B. Estes 2009 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by MARK B. ESTES entitled Paleoindian Occupations In The Great Basin: A Comparative Study Of Lithic Technological Organization, Mobility, And Landscape Use From Jakes Valley, Nevada be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Gary Haynes, Ph.D., Advisor Michael R. Bever, Ph.D., Committee Member Ted Goebel, Ph.D., Committee Member P. Kyle House, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Associate Dean, Graduate School May, 2009 i Abstract Previous research on Paleoindian occupations in the Great Basin has provided many more questions than answers. Central to understanding this early period is the relationship between its Western Fluted and Western Stemmed Tradition occupants. Little is known of the temporal, cultural, and technological behaviors of Western Fluted peoples, while the Western Stemmed Tradition inhabitants are only slightly better understood. This thesis presents the results of intensive technological studies that focused on determining raw material provisioning strategies, lithic conveyance zones, and landscape use to identify mobility and settlement patterns. Lithic assemblages from 19 Paleoindian era occupations, encompassing several environmental zones within Jakes Valley in eastern Nevada, provide data on the technological organization and movement patterns of early humans in the Great Basin, and reveal previously unknown behaviors that help differentiate the early hunter-gatherer groups who made Fluted and Stemmed projectile points. -

Vol. 86 Friday, No. 13 January 22, 2021 Pages 6553–6824

Vol. 86 Friday, No. 13 January 22, 2021 Pages 6553–6824 OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL REGISTER VerDate Sep 11 2014 22:05 Jan 21, 2021 Jkt 253001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\22JAWS.LOC 22JAWS jbell on DSKJLSW7X2PROD with FR_WS II Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 13 / Friday, January 22, 2021 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office PUBLIC of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, under the Federal Register Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) Subscriptions: and the regulations of the Administrative Committee of the Federal Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Government Publishing Office, is the exclusive distributor of the official edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general (Toll-Free) applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published FEDERAL AGENCIES by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public Subscriptions: interest. Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions: Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the Email [email protected] issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

The Alaskan Caver

THE ALASKAN CAVER NSS Convention '82 BEND, OREGON ~AnnoJ~~ntumorLlrN.tr~l-~ CONWMToW CHAIlWUH mCuAmMM4 UNY. Dm 8106 5 E Cdlllrn S'.M 52' Wm Sn*ll b~anoOr-m 97706 -- Mnn ¶m8yli- NSS rrt (XU! 114 773 Canma vw u 6nva~ron [6%1352-'Wx htw: June 27th to July 3r4. 1982 lh 1982 Oonwntion staff is putting out a call for mrsfur th sasaions to k hald In Bend, 0-n Qlrlw 1982. Pleaom sham yew Info*mation and -rim- at one of the 808810~t8. Papers on all typas of cadw subjects are an-&. If you am willing to qiw a mr, plsaao cantad eitbr your section chiman or the Prqr- Chima for the Convention. Wstracto of 300 worda or laan are nuby &ah l6t. 'Ybsr are to k pmtdin the FTiOXAH of the Convention and in a spscial M BULGgTII. You will, am the nm an$ nddrssa of the psraon to sand your abstract to in the W m. Wa will hold all of thm earsessions, m.g. Biow, Wloqg, Vertical, Social Sclenca, Wmmn'~, ere. as Wll as s- mmcial wssions such an: A Safety & TwWquen maimwith mrnim asmaion of pwra and an aft*mn seasfon in n cave. Wrman, Joe Facklsr, 2404 bntend St., hiss, fD 85702. 10s and his Idaho Rescum Group bw - mt im! Vnlcanosp.lwlomr -8iwn. Bill fhllldhg ia ergani~~this one1 Bill's address ix 1117 36th Avo. E, Seattle, 'dA 98112. kdhPrsst Dfrsrsfe @mpoaium. In cue ym Wnk d1 caves in tb Wad ars formed af basalt (i.s., lava), Phil Ntfbald 3a pmto ahou you th wide diversity of caves! Rfchard Hall has already wluntwrd to tell as about mCavas & Cave Potmttial In Alaska." You will hear abut other qrwt caving areau that you may n& know adst in the West! Special Progrm on Ht. -

Chapter 13 Chipped Stone Bifaces As Cultural, Behavioural, And

Chapter 13 Chipped Stone Bifaces as Cultural, Behavioural, and Temporal Indices on the Central Canadian Plateau Mike K. Rousseau Antiquus Archaeological Consultants Ltd., Maple Ridge B.C. V4R 0A8 • Email: [email protected] Over the last three and a half decades, archaeo- to successfully extract and utilize resources within logical investigations on the Canadian Plateau have a wide range of local environmental niches, and to resulted in definition of several ubiquitous and cope with significant environmental and climatic distinctive chipped stone formed bifacial projectile changes spanning many millennia. Chipped stone point and knife types. Many have been successfully bifaces were an important and integral aspect of employed as temporal horizon markers for relative these cultural and technological systems, and with dating, others for interpreting and reconstructing the proper reconstruction and understanding of past human behaviour, and a few have been used for their role(s) and significance, a great deal of behav- developing models of cultural/ethnic group origins, ioral and ethnic information can be inferred from identity, and inter-regional group interaction. This them. chapter provides general and detailed descriptions The Early Prehistoric (pre-contact) Period from of recognized “diagnostic” biface types found on the ca. 11,000 to 7000 BP is still very poorly understood, central aspect of Canadian Plateau (Figure 1) over nevertheless, both solid and tenuous data have been the last 11,000 years. It also summarizes what is gathered. Rousseau (1993) and Stryd and Rousseau currently known about initial appearance and ter- (1996:179−185) have summarized what is currently mination dates for various bifacial implement forms known, and additional information is presented and their persistence through time; suspected and/or herein.