The Nuclear Education of Donald J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

His Majesty Conferred with Top Russian Honour by Demonstrations Against Manama Corruption and the Coun- Prof Naumkin Lauded HM the Tries Political Leaders

TWITTER CELEBS @newsofbahrain OP-ED 8 The US political system is about to be tested in an extraordinary way INSTAGRAM Rachel Weisz /nobmedia 30 to play Elizabeth LINKEDIN WEDNESDAY newsofbahrain OCTOBER 2019 Taylor in biopic 210 FILS WHATSAPP ISSUE NO. 8280 Rachel Weisz is set 38444692 to star as Elizabeth FACEBOOK Taylor in “A Special /nobmedia Relationship”, exploring MAIL Taylors journey from [email protected] actress to activist. WEBSITE P14 newsofbahrain.com Brave CF lands in Romania to start ‘something special’, says Mohammed Shahid 16 SPORTS WORLD 5 Nawaz Sharif fighting for life: doctor Hariri resigns Beirut ebanon’s Prime Minister LSaad Hariri submitted his resignation on Tuesday in response to widespread protests against the coun- try’s leaders. In a TV address to the nation Hariri said he had reached a “dead end,” and that he would submit his resignation to President Michel Aoun. Lebanon has been rocked His Majesty conferred with top Russian honour by demonstrations against Manama corruption and the coun- Prof Naumkin lauded HM the tries political leaders. is Majesty King Hamad King’s wise policy to strengthen On Monday violence bin Isa Al Khalifa yester- political, economic and social erupted when a mob loy- Hday received, at Al Sakhir relations between the Kingdom al to Hezbollah and Amal Palace, Professor Vitaliy Naum- of Bahrain and the Russian Fed- attacked and destroyed a kin, President of the Institute of eration, on the basis of mutual protest camp set up by an- Oriental Studies of the Russian respect and common interests. ti-government demonstra- Academy of Sciences, marking his The board of trustees of the tors in Beirut. -

PDF (Interactive)

Contents 21ST-CENTURY FASCISM & RESISTANCE Study for Struggle: Weaponizing Theory for the Fights Ahead 1 Rachel Herzing & Isaac Ontiveros Trumpism, 21st-Century Fascism, and the Dictatorship of the Transnational Capitalist Class 5 William I. Robinson ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY Social Justice, Environmental Destruction, and the Trump Presidency: A Criminological View 8 Michael J. Lynch, Paul B. Stretesky, Michael A. Long & Kimberly L. Barrett Orange is the New Green: The Environmental Justice Implications of Trump’s EPA 13 Jordan E. Mazurek HEALTH CARE Trump’s Health Care Agenda 18 Thomas Bodenheimer IMMIGRATION Donald Trump and Immigration: A Few Predictions 22 Ray Michalowski The “Immigrant Problem”: A Historical Review and the New Impacts under Trump 26 Marla A. Ramírez INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Some Aspects of the Trump Administration’s Foreign Policy 30 Gregory Shank Latin America vs. Trump 35 Clifford Welch LABOR & CLASS Meet the New Boss, Same as the Old Boss: Bracing for Trump’s Anti-Worker, Corporate Agenda 39 Colin Jenkins LGBTQ POLITICS A Queer Exemption? What Trump’s Presidency Means for LGBTQ Politics 43 Clare Sears PENAL POLITICS Punishment and Policing in the Trump Era 47 Michelle Brown Neoliberal Authoritarianism: Notes on Penal Politics in Trump’s America 51 Alessandro De Giorgi RACE & RACISM Donald Trump and Race 55 Jason Williams WELFARE POLICY The End Of Welfare? 59 Gwendolyn Mink Death by a Thousand Budget Cuts: The Need for a New Fight for Poor People’s Rights 62 Tina Sacks WOMEN’S ISSUES AND REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS Gender and Trump 65 Carol C. Mukhopadhyay Statement of the SJ Editorial Board on the Election of Donald Trump 69 About SJ Social Justice: A Journal of Crime, Conflict & World Order (ISSN: 1043–1578) is a peer-reviewed quarterly journal that offers analyses of the wide array of issues that shape our critical understanding of the present and inform current struggles for social justice—crime and social control, human rights, borders and migrations, labor and capital, environmental justice, education, race, gender, and sexuality. -

Populist Conservatism Or Conservative Populism? the Republican Party, the New Conservative Revolution and the Political Education of Donald Trump

Populist conservatism or conservative populism? The Republican Party, the new Conservative Revolution and the political education of Donald Trump Introduction The American experience with populism – both empirical and theoret- ical – is very dissimilar to the European or even Latin American ones. The partisan framework of the nascent American democracy, its staunchly liberal intellectual foundations, but also the inbuilt racial and social tensions at the heart of the system, shaped along the 19th and 20th century a peculiar understanding of the main political categories of polity, politics and policy. These elastic labels make a pertinent in- ternational analysis of the content of the pop- ulist – or for that matter of the conservative – Alexis CHAPELAN label a difficult and challenging endeavor. Our paper will strive to map out the intellec- PhD student, Ecole des Hautes Etudes tual roots and the ideological expressions of en Sciences Sociales an uniquely American form of populism, in [email protected] the context of a federal republic whose expe- rience of democracy and liberalism, both at national and state level, is fundamentally dif- ferent from that of other Western developed countries. After briefly en- gaging in a theoretical exploration of the two main labels used in this study – namely populism and conservatism -, we aim to further ques- tion the nature of the trumpian breed of anti-establishment politics and the intricate relationship it developed with on the one hand the “main- stream” Republican conservative, and on the other hand with the far- right nebulae crystallizing in the murky no-man’s-land at the right of the Grand Old Party. -

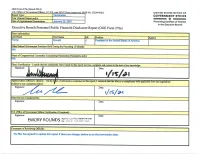

Financial Disclosure Report (OGE Form 278E)

OGE Form 278e (March 2014) U.S. Office of Government Ethics· 5 C.F.R. art 2634 Form A roved: 0MB No. (3209-0001) UNIT£0 STATES O FflCE O F R rt T Tennination GOVERNM ENT ETHICS Date of Appointment/Termination: January 20, 2021 Preventing Confli* cts of lntere,t in the Execu:ive Bran<:h Executive Branch Personnel Public Financial Disclosure Report (OGE Form 278e) Filer's Information •L . Last Name First Name MI Position Agency Trump Donald J President of the United States of America Other Federal Government Positions Held During the Preceding 12 Months: N/A Name of Congressional Committee Considering Nomination (Nominees only): N/A Filer's Certification - I certify that the statements I have made in this report are true, complete and correct to the best of my knowledge: Signature: Date: JJMi •/•'r/- • Agency Ethics Otticial's upwon - Ori the i1.1s of mtormation contained m llllS report, I conclude that the filer 1s in compliance with applicable laws and regulations (subject to any comments be]ow) - Signature: Date: ~ 1/ ,s/ ;;-c Other Review Conducted By: Signature: Date: U.S. Office ofGovernment Ethics Certification (if required): Signature: Date: Comments of Reviewing Officials: The filer has agreed to update this report if there are changes before or on the termination date. OGE Form 278e (March 2014) Instructions for Part 1 Note: This is a public form. Do not include account numbers, street addresses, or family member names. See instructions for required information. Filer's Name Page Number Donald J. Trump 2 of 37 Part 1: Filer's Positions Held Outside United States Government # Organization Name City/State Organization Type Position Held From To 1. -

AMERICA in the TIME of TRUMP Special Edition

AMERICA IN THE TIME OF TRUMP Special Edition May 2018 Dear readers, It’s been over a year since Donald Trump’s inauguration as 45th President of the United States of America. The repercussions of this election have been felt across the globe and here in France we have decided to turn our attention to the home of the brave and its controversial President in order to take stock of the situation. We are embarking on a journey which will take you from Trump’s childhood, the tale of which is told by Gabrielle Colas in her tremendous bedtime story, to the case of an ordinary French boy swept up in the American far-right from the perspective of one of his friends, Rayan Dequin. On the way we will explore Trump’s relationship with religion with Solène Garnier de Boisgrollier and Antoine Larcher, from the President’s recent stance on his “heavenly Jerusalem” to the massive support he has received from the American Evangelical population. We will also try to make sense of Trump’s stance on gun control with Manon Fossemale. If Trump’s policies are sometimes hard to understand, it may be due to his infamous style of speech but Milena Kerner is here to help you make sense of it all with an analysis of his use of language. We will also look to certain groups who have felt attacked and subsequently retaliated against Trump, with Tatiana Wegner’s piece on feminism and Charlyze Anguiley’s article on politically engaged hip-hop. Have a good trip. -

Donald Trump November 3, 2015

2016 Presidential White Paper SERIES Paper #11 donald trump November 3, 2015 INTRODUCTION of New York7 and planned to challenge Pat Buchanan for the Reform Party presiden- Donald Trump is a career businessman tial nomination, but eventually withdrew and real estate developer whose personal calling the party a “total mess.”8 fortune from real estate and television has been valued by Forbes at $4.5 billion1, Trump registered as a Democrat in 2001, however Trump says his worth should and remained a Democrat for the next be valued in excess of $10 billion2, while eight years. He also was an outspoken Photo credit: Gage Skidmore Bloomberg’s analysis pegged it at $2.9 bil- critic of President George W. Bush – even lion.3 Forbes gives Trump a score of 5 out urging Nancy Pelosi to impeach him9 – loopholes” that he claims would be reduced of 10 on its Self-Made Score, an indica- before rejoining the Republican Party in or eliminated.12 In addition, the Trump tion that at least some of his wealth was 2009.10 However, he took another leave tax proposal includes a one-time 10% inherited.4 Trump’s father was a New York of absence from the GOP in 2011 before repatriation tax on “…corporate cash held real estate developer who, according to the returning in April 2012.11 In both 2008 and overseas… followed by an end to the defer- Washington Post, “…built an empire of some 2012 Trump hinted at possible presidential ral of taxes on corporate income earned 27,000 residential units… and was worth runs, but ultimately set his sights on the abroad.”13 Conservatives have generally nearly $300 million at his death in 1999.”5 2016 Republican presidential nomination. -

THE LEVERA GE PARADO X

The Leverage Paradox: Pakistan and the United States Hathaway ASIA PROGRAM ASIA PROGRAM Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org ISBN: 978-1-938027-74-1 Copyright 2017, All Rights Reserved Cover illustration by Joshua Spooner Give me a lever and a place to stand, and I will move the earth. Archimedes The strong do what they can, while the weak suffer what they must. Thucydides When you owe the bank a hundred dollars, you have a problem; but when you owe the bank $100 million, the bank has a problem. J. Paul Getty Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Preface, by Hon. Lee H. Hamilton 7 Acknowledgments 11 Introduction 15 I Roller Coaster Partnership 33 II Alliance Restored 55 III Alliance Stalemate 81 IV Deflecting Pressure, Maximizing Leverage 115 Afterword: Donald Trump and Leverage 143 Chart: U.S. Overt Aid to Pakistan, 1948 - 2016 157 About the Author 161 PAKISTAN Administrative Divisions UZBEKISTAN DUSHANBE TAJIKISTAN TURKMENISTAN CHINA GILGIT- Gilgit BALTISTAN KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA 72 Line l 19 of Contro KABUL Muzaffarābād Pesha¯war AZAD AFGHANISTAN KASHMIR ISLAMABAD FEDERALLY ISLAMABAD ADMINISTERED CAPITAL TRIBAL TERRITORY** AREAS* Lahore PUNJAB Quetta NEW DELHI BALOCHISTA¯N IRAN INDIA SINDH International boundary Province-level boundary Karachi National capital Province-level capital Pakistan has four provinces, one territory*, and one capital territory**. The Pakistani-administered portion of the disputed Jammu and Kashmir region consists of two administrative entities: Arabian Sea Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan. Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan are not constitutionally part of Pakistan. -

Pengantar APRIL 2014

TERAKREDITASI NO 2/E/KPT/2015 JURNAL HUBUNGAN INTERNASIONAL | VOL. 5 | NO. 2| OKTOBER 2016 - MARET 2017 P-ISSN 1829-5088 E-ISSN 2503-3883 Ketua Penyunting Ade Marup Wirasenjaya Sekretaris Penyunting Sidiq Ahmadi Dewan Penyunting Tulus Warsito Ali Muhammad Ali Maksum Takdir Ali Mukti Ratih Herningtyas Sugito JURNAL HUBUNGAN INTERNASIONAL Sugeng Riyanto adalah jurnal ilmiah berkala yang diterbitkan oleh Omi Ongge Masyithoh Annisa Ramadhani Jurusan Ilmu Hubungan Internasional, Fakultas Faris Alfadhat Ilmu Sosial dan Politik, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta. Terbit dua kali Staf Penyunting setahun pada bulan April-Oktober dan Novem- Wilda Fatma Apsari ber-Maret. Redaksi menerima naskah artikel hasil Kesekretariatan penelitian dan artikel gagasan dalam selingkung Nurbiyanto ilmu hubungan internasional. Panjang naskah 15 sampai 25 halaman kwarto (A4) dengan spasi 1,5. Alamat Redaksi Naskah dilengkapi dengan biodata penulis. Gedung Ki Bagus Hadi Kusumo, E4 Lantai 1, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik, Kampus Terpadu Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta Ringroad Tamantirto, Kasihan, Bantul, Yogyakarta, Tel. 0274-387656 Email: [email protected] website: journal.umy.ac.id/index.php/jhi JURNAL HUBUNGAN INTERNASIONAL II VOL. 5 EDISI 2 / OKTOBER 2016-MARET 2017 Daftar isi VOL. 5 - NO. 2, OKTOBER 2016 - MARET 2017 113 - 123 Pendekatan Konstruktivis dalam Kajian Diplomasi Publik Indonesia IVA RACHMAWATI; Prodi Ilmu Hubungan Internasional, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Politik Universitas Pembangunan Nasional “Veteran” Yogyakarta 124 - 136 Turkish -

How to Get Rich

▼How to Get Rich ◄ 2 ► ▼How to Get Rich Contents Title Page Dedication Introduction Five Billion Reasons Why You Should Read This Book PART I The Donald J. Trump School of Business and Management PART II Your Personal Apprenticeship (Career Advice from The Donald) PART III Money, Money, Money, Money PART IV The Secrets of Negotiation PART V The Trump Lifestyle ◄ 3 ► ▼How to Get Rich PART VI Inside The Apprentice Acknowledgments Appendix Behind the Scenes at the Trump Organization About the Author Also by Donald J. Trump Copyright ◄ 4 ► ▼How to Get Rich To my parents, Mary and Fred Trump ◄ 5 ► ▼How to Get Rich The Mother of All Advice Trust in God and be true to yourself. —Mary Trump, my mother When I look back, that was great advice, concise and wise at once. I didn’t really get it at first, but because it sounded good, I stuck to it. Later I realized how comprehensive this is—how to keep your bases covered while thinking about the big picture. It’s good advice no matter what your business or lifestyle. —DJT ◄ 6 ► ▼How to Get Rich TRUMP How to Get Rich ◄ 7 ► ▼How to Get Rich Introduction Five Billion Reasons Why You Should Read This Book A lot has happened to us all since 1987. That’s the year The Art of the Deal was published and became the bestselling business book of the decade, with over three million copies in print. (Business Rule #1: If you don’t tell people about your success, they probably won’t know about it.) A few months ago, I picked up The Art of the Deal, skimmed a bit, and then read the first and last paragraphs. -

Shelf Order for Holdings Code UHS Library Biography (UHSBIO)

Shelf Order for Holdings Code UHS Library Biography (UHSBIO) Call Call Call Call Number Cutter Sorted Call Number Author Title Number Number Number Type Prefix Class X B 50 CENT B 50 CENT Marcovitz, Hal. 50 Cent X B 50 CENT B 50 CENT Uschan, Michael 50 Cent V., 1948- X B AARON B AARON Aaron, Hank, I had a hammer : the Hank Aaron story 1934- X B AARON B AARON Poolos, Jamie Hank Aaron X B ABDUL-JABBAR B ABDUL-JABBAR Abdul-Jabbar, Giant steps Kareem, 1947- X B ABDUL-JABBAR B ABDUL-JABBAR Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem Kareem, 1947- X B ABIRACHED B ABIRACHED Abirached, Zeina, I remember Beirut 1981- X B Ada B Ada Bober, Natalie. Abigail Adams : witness to a revolution X B ADAMS B ADAMS Bowen, John Adams and the American Catherine Revolution. Drinker, 1897-1973. X B ADAMS B ADAMS Clarke, Fred G John Quincy Adams. X B ADAMS B ADAMS Gelles, Edith Abigail Adams : a writing life Belle. X B ADAMS B ADAMS McCullough, John Adams David G. X B ADAMS B ADAMS Nagel, Paul C. John Quincy Adams : a public life, a private life X B ADAMS B ADAMS Remini, Robert John Quincy Adams Vincent, 1921- X B ADAMS B ADAMS Strangis, Joel Ansel Adams : American artist with a camera X B ADDAMS B ADDAMS Fishwick, Illustrtious Americans: Jane Addams, Marshall William X B ADDAMS B ADDAMS Fradin, Judith Jane Addams : champion of democracy Bloom X B ADDAMS B ADDAMS Hovde, Jane. Jane Addams X B ADDAMS B ADDAMS Kittredge, Mary, Jane Addams 1949- X B ADDAMS B ADDAMS Knight, Louise W. -

Trump Revealed

NOTES PROLOGUE: “PRESIDENTIAL” 1 “can’t out-top Abraham Lincoln”: Trump interview with Robert Costa and Bob Woodward, Washington Post, April 1, 2016. 3 “I’m the Lone Ranger”: Ibid. 4 “your guard up”: Filmed interview with Errol Morris, 2002, https://www.youtube .com/watch?v=upC8pX3RY0A. 4 “making the country better”: Trump interview with Marc Fisher and Michael Kra- nish, April 21, 2016. 5 they should be allowed: “Donald Trump: ‘Be Careful!,’ ” Chicago Sun-Times, March 23, 2015. 5 noisy jets roaring: “Decade-Old Plan to Extend Palm Beach Airport Runway Revived,” Associated Press, March 23, 2015. 5 reversed course: Brian Swanson, Scottish Express, March 22, 2015, 31. 5 “celebrity video cameo”: “Radio City: Excitement Continues to Build around New York Spring Spectacular,” Globe Newswire, March 23, 2015. 5 “marketing genius”: Hardball, MSNBC, March 23, 2015. 5 “fictional presidential campaigns”: Jeffrey Toobin on The Situation Room, CNN, March 23, 2015. 5 “growing swarm”: Philip Rucker and Robert Costa, “With Cruz In, Race for GOP Right Heats Up,” Washington Post, March 23, 2015. 5 “entire year’s salary”: Up with Steve Kornacki, MSNBC, March 21, 2015. 5 oddsmakers were betting: “Odds of Ted Cruz Winning White House Sit at 33–1,” Chicago Sun-Times, March 23, 2015. 6 “tired of glib talk”: Joe McQuaid, “Publisher’s Notebook,” New Hampshire Union Leader, March 23, 2015, 1A. 6 “just a tease”: Trump, on The Kelly File, Fox News Channel, March 23, 2015. 10 “germs on your hands”: Trump interview with Fisher and Kranish. 12 “The part that”: Paul Manafort, quoted in “Trump Is Playing a Part and Can Transform for Victory,” Washington Post, April 21, 2016. -

CIGS Jeffrey Steinberg Seminar

CIGS Jeffrey Steinberg Seminar The Trump Presidency after 18 Months (Summary of speech) Date: 11 July, 2018 Venue: CIGS Meeting Room, Tokyo, Japan CopyrightⒸ2018 CIGS. All rights reserved. Jeffrey Steinberg, Executive Vice President, Pacific Tech Bridge (PTB): I assume that during the autumn of 2016, many of you heard that it was 100% certain that Hillary Clinton would be the next President of the United States. That is obviously not what happened and there were many factors that were ignored by the traditional Washington D.C. political establishment. They were so invested in the wrong outcome that to this day they refuse to accept the reality, and instead are looking for all kinds of excuses. The mood in the United States was one of deep frustration with continuity of establishment policies, specifically the continuation of wars without end, the bailout of Wall Street, disinvestment in the real economy of the United States, and the continuing collapse of very basic infrastructure. There was a mandate to pull a circuit breaker on the direction of policy. Now, unfortunately there was no candidate for either party who really represented a positive alternative. The net effect was that you got Donald Trump, who reflected the mood inside the country. In 2000, Trump wrote a book, called The America We Deserve. The major theme of the book is Trump announcing that he’s planning to run for president, 16 years before he ran. He wrote that we may be facing an economic crash like we've never seen before, and we have to anticipate it and know how to rebound.