Challenging Nostalgia and Performance Metrics in Baseball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again?

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again? INTRODUCrION "Baseball is everybody's business."' We have just witnessed the conclusion of perhaps the greatest baseball season in the history of the game. Not one, but two men broke the "unbreakable" record of sixty-one home-runs set by New York Yankee great Roger Maris in 1961;2 four men hit over fifty home-runs, a number that had only been surpassed fifteen times in the past fifty-six years,3 while thirty-three players hit over thirty home runs;4 Barry Bonds became the only player to record 400 home-runs and 400 stolen bases in a career;5 and Alex Rodriguez, a twenty-three-year-old shortstop, joined Bonds and Jose Canseco as one of only three men to have recorded forty home-runs and forty stolen bases in a 6 single season. This was not only an offensive explosion either. A twenty- year-old struck out twenty batters in a game, the record for a nine inning 7 game; a perfect game was pitched;' and Roger Clemens of the Toronto Blue Jays won his unprecedented fifth Cy Young award.9 Also, the Yankees won 1. Flood v. Kuhn, 309 F. Supp. 793, 797 (S.D.N.Y. 1970). 2. Mark McGwire hit 70 home runs and Sammy Sosa hit 66. Frederick C. Klein, There Was More to the Baseball Season Than McGwire, WALL ST. J., Oct. 2, 1998, at W8. 3. McGwire, Sosa, Ken Griffey Jr., and Greg Vaughn did this for the St. -

Visit the Hall of Stats at Hallofstats.Com. Follow the Hall of Stats on Twitter at @Hallofstats

The Hall of Stats is populated by a formula called Hall Rating. A player needs a Hall Rating of 100 to gain induction, so Alan Trammell and his 143 Hall Rating sit comfortably in the Hall of Stats. In fact, Trammell’s Hall Rating is better than 70% of Hall of Famers. For a complete explanation of the Hall Rating formula, similarity scores, and much more, visit: hallofstats.com/about The Hall of Stats The Hall of Stats ranks An alternate Hall of Fame populated by a mathematical formula. every player in history—all 17,941 of them. There are also rankings by position Research and design by Adam Darowski ([email protected]) and by franchise. Built by Adam Darowski, Jeffrey Chupp, and Michael Berkowitz (hallofstats.com) Each player’s value is broken down by franchise. Rather than raw career The Hall of Stats was conceived because the Hall of Fame voting process has statistics, the Hall of Stats become a political nightmare. A massive backlog of worthy candidates is piling displays WAR and WAA up—some because of association with PEDs (or simply suspicion), but some because (before and after voters just don’t realize how good they were. There seems to be a false perception of adjustments). what the Hall of Fame actually is. It’s not all Babe Ruth, Christy Mathewson, Ty Cobb, Each player’s WAR and Honus Wagner. For every Walter Johnson in the Hall of Fame there’s a Jesse components (batting, Haines. For every Hank Aaron there’s a Tommy McCarthy. basrunning, avoiding the double play, fielding, and Should each player better than Haines and McCarthy get in? No. -

By Kimberly Parkhurst Thesis

America’s Pastime: How Baseball Went from Hoboken to the World Series An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Kimberly Parkhurst Thesis Advisor Dr. Bruce Geelhoed Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April 2020 Expected Date of Graduation July 2020 Abstract Baseball is known as “America’s Pastime.” Any sports aficionado can spout off facts about the National or American League based on who they support. It is much more difficult to talk about the early days of baseball. Baseball is one of the oldest sports in America, and the 1800s were especially crucial in creating and developing modern baseball. This paper looks at the first sixty years of baseball history, focusing especially on how the World Series came about in 1903 and was set as an annual event by 1905. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Carlos Rodriguez, a good personal friend, for loaning me his copy of Ken Burns’ Baseball documentary, which got me interested in this early period of baseball history. I would like to thank Dr. Bruce Geelhoed for being my advisor in this process. His work, enthusiasm, and advice has been helpful throughout this entire process. I would also like to thank Dr. Geri Strecker for providing me a strong list of sources that served as a starting point for my research. Her knowledge and guidance were immeasurably helpful. I would next like to thank my friends for encouraging the work I do and supporting me. They listen when I share things that excite me about the topic and encourage me to work better. Finally, I would like to thank my family for pushing me to do my best in everything I do, whether academic or extracurricular. -

A Whole New Ball Game: Sports Stadiums and Urban Renewal in Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and St

A Whole New Ball Game: Sports Stadiums and Urban Renewal in Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis, 1950-1970 AARON COWAN n the latter years of the 1960s, a strange phenomenon occurred in the cities of Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis. Massive white round Iobjects, dozens of acres in size, began appearing in these cities' down- towns, generating a flurry of excitement and anticipation among their residents. According to one expert, these unfamiliar structures resembled transport ships for "a Martian army [that] decided to invade Earth."1 The gigantic objects were not, of course, flying saucers but sports stadiums. They were the work not of alien invaders, but of the cities' own leaders, who hoped these unusual and futuristic-looking structures would be the key to bringing their struggling cities back to life. At the end of the Second World War, government and business leaders in the cities of Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and St. Louis recognized that their cities, once proud icons of America's industrial and commercial might, were dying. Shrouded in a haze of sulphureous smoke, their riparian transportation advantages long obsolete, each city was losing population by the thou- sands while crime rates skyrocketed. Extensive flooding, ever the curse of river cities, had wreaked havoc on all three cities' property values during 1936 and 1937, compounding economic difficulties ushered in with the Riverfront Stadium in Great Depression. While the industrial mobilization of World War II had Cincinnati. Cincinnati brought some relief, these cities' leaders felt less than sanguine about the Museum Center, Cincinnati Historical Society Library postwar future.2 In 1944, the Wall Street Journal rated Pittsburgh a "Class D" city with a bleak future and little promise for economic growth. -

Clips for 7-12-10

MEDIA CLIPS – May 8, 2018 Inbox: When will Tapia rejoin Rockies in bigs? Beat reporter Thomas Harding answers fans' questions Thomas Harding / MLB.com | May 7, 2018ng_at_mlb DENVER -- The Rockies have won five straight because of standout starting pitching, but the offense, which hasn't found its groove, generates questions for this week's Inbox. Let's take a look at some of your questions: Thomas Harding @harding_at_mlb Let's try this again. Send me your #Rockies questions and I will answer in a story before tosay's series finale with #Cubs Adam Arias @Adi2zz6le How come we have not seen tapia up yet ? And is there a chance we trade Desmond, cargo and parra? We could clear room to resign DJ Raimel Tapia homered four times in the first seven games with Triple-A Albuquerque this season, but he was struggling with strikeouts -- 15 in his first 11 games. He has been far better over his past 18 games -- .346 with 18 runs scored, one homer, seven doubles and two triples. Now it's just simply a matter of finding a place for him. He's in that tough position of having to force the organization's hand, or at least stay hot until an injury occurs. 1 Despite the shouting about the slow starts of Ian Desmond and Carlos Gonzalez (Gerardo Parra has been respectable with a .263 average and a .327 on-base percentage), teams don't drop veterans they've invested in after a bad month. And with Desmond, who's owed a good chunk of money in the second year of a five-year contract, and Gonzalez struggling, it's not like there is huge grade value. -

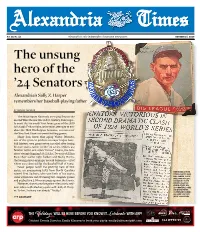

OCTOBER 24, 2019 the Unsung Hero of the ’24 Senators Alexandria’S Sally Z

Alexandria Times Vol. 15, No. 43 Alexandria’s only independent hometown newspaper. OCTOBER 24, 2019 The unsung hero of the ’24 Senators Alexandria’s Sally Z. Harper remembers her baseball-playing father BY DENISE DUNBAR The Washington Nationals are vying for just the second World Series title in D.C. history. Fans eager- ly await the Nationals’ first home game of the 2019 fall classic Friday night as the team attempts to em- ulate the 1924 Washington Senators, winners over the New York Giants in seven thrilling games. Many fans know that aging Walter Johnson, one of the greatest pitchers in major league base- ball history, won game seven in relief after losing his two starts earlier in the ‘24 series. Others are familiar with Leon Allen “Goose” Goslin, the Sen- ators’ young slugging left fielder; 34-year-old Sam Rice, their stellar right fielder; and Bucky Harris, the young player-manager second baseman – all of whom were destined for the Baseball Hall of Fame. Fewer people recall the pitching hero of that series, an unassuming lefty from North Carolina MEMORABILIA FROM named Tom Zachary, who won both of his starts, TOM ZACHARY'S BASE- came within one out of tossing two complete games BALL CAREER, CLOCK- WISE FROM TOP LEFT: and pitched to a 2.04 run average against the Giants. HIS WATCH FOB FOR However, there’s one longtime Alexandria resi- WINNING THE 1924 WORLD SERIES, HIS dent who recalls Zachary quite well: Sally Z. Harp- 1933 BASEBALL CARD er. To her, Zachary was simply “Daddy.” AND A NEWSPAPER CLIPPING DESCRIBING HIS GAME 2 VICTORY SEE ZACHARY | 6 IN THE 1924 SERIES. -

Ou Know What Iremember About Seattle? Every Time Igot up to Bat When It's Aclear Day, I'd See Mount Rainier

2 Rain Check: Baseball in the Pacific Northwest Front cover: Tony Conigliaro 'The great things that took place waits in the on deck circle as on all those green fields, through Carl Yastrzemski swings at a Gene Brabender pitch all those long-ago summers' during an afternoon Seattle magine spending a summer's day in brand-new . Pilots/Boston Sick's Stadium in 1938 watching Fred Hutchinson Red Sox game on pitch for the Rainiers, or seeing Stan Coveleski July 14, 1969, at throw spitballs at Vaughn Street Park in 1915, or Sick's Stadium. sitting in Cheney Stadium in 1960 while the young Juan Marichal kicked his leg to the heavens. Back cover: Posing in 1913 at In this book, you will revisit all of the classic ballparks, Athletic Park in see the great heroes return to the field and meet the men During aJune 19, 1949, game at Sick's Stadium, Seattle Vancouver, B.C., who organized and ran these teams - John Barnes, W.H. Rainiers infielder Tony York barely misses beating the are All Stars for Lucas, Dan Dugdale, W.W. and W.H. McCredie, Bob throw to San Francisco Seals first baseman Mickey Rocco. the Northwestern Brown and Emil Sick. And you will meet veterans such as League such as . Eddie Basinski and Edo Vanni, still telling stories 60 years (back row, first, after they lived them. wrote many of the photo captions. Ken Eskenazi also lent invaluable design expertise for the cover. second, third, The major leagues arrived in Seattle briefly in 1969, and sixth and eighth more permanently in 1977, but organized baseball has been Finally, I thank the writers whose words grace these from l~ft) William played in the area for more than a century. -

Rockville Cemetery Association DECEMBER 2014

Rockville Cemetery Association DECEMBER 2014 President’s Message Rockville Cemetery continues to pros- McGuckian as secretary; Tim Mertz etery. Fred installs commemorative per as 2014 comes to a close. Gravesite continues as our treasurer. As our only fl ags on all known veteran graves for sales were steady; nearly twenty buri- professional cemeterian, Tom Claxton Memorial and Veterans Day. Let us als occurred this year. Both upper and continues to lend his expertise to the know if there is a veteran who is not lower columbaria had inurnments. board’s decisions. We welcomed a new on our list, which will be added to the Gravestone conservation remains a board member, Ellen Buckingham. website this winter. key priority; our contractor Robert Ellen is already contributing with lead- A big thanks to the Rockville Mosko performed dozens of repairs in ership on the website upgrade project, Rotary Club Foundation for another 2014. Solar Gardens continued their an important priority going forward. generous grant of $5,000, slated for steady quality work maintaining the Check www.rockvillecemeterymd.org additional interior road repairs in the grounds in tidy and attractive condi- to follow our progress. upper section. Th e biggest project on tion. Several large trees in the upper Another board priority, converting our list, the opening of a new section cemetery are in poor condition, re- RCA’s voluminous records to digital for graves on the north side of the up- quiring trimming or removal. A series format continues under the guidance per cemetery, remains on hold pend- of repairs to the 1889 house have kept of volunteer Michael Grant. -

Challenging Nostalgia and Performance Metrics in Baseball

Challenging nostalgia and performance metrics in baseball Daniel J. Eck October 29, 2018 Abstract We show that the great baseball players that started their careers before 1950 are overrepresented among rankings of baseball’s all time greatest players. The year 1950 coincides with the decennial US Census that is closest to when Major League Baseball (MLB) was integrated in 1947. We also show that performance metrics used to compare players have substantial era biases that favor players who started their careers before 1950. In showing that the these players are overrepresented, no individual statistics or era adjusted metrics are used. Instead, we argue that the eras in which players played are fundamentally different and are not comparable. In particular, there were significantly fewer eligible MLB players available at and before 1950. As a consequence of this and other differences across eras, we argue that popular opinion, performance metrics, and expert opinion over include players that started their careers before 1950 in their rankings of baseball’s all time greatest players. 1 Introduction It is easy to be blown away by the accomplishments of great old time baseball players when you look at their raw or advanced baseball statistics. These players produced mind-boggling numbers. For example, see Babe Ruth’s batting average and pitching numbers, Honus Wagner’s 1900 season, Ty Cobb’s 1911 season, Walter Johnson’s 1913 season, Tris Speaker’s 1916 season, Rogers Hornsby’s 1925 season, Lou Gehrig’s 1931 season, and many others. The statistical feats achieved by these players (and others) far surpass what the statistics that recent and current players produce. -

“ Ice Box Bandits” Were Seen by Many

NET PRESS RUN' AVERAGE DAILY CIRCULATION for the month of August, 1028 Fair and cooler tonight; - Satnr*: day increasii^ clc|Qdinefis 'and" 5 , 1 2 5 su b tly warmcir.- .> Member of the Audit Bureau of tonn. State Library . CIrvnIntiona__________ _ PRICBJ THRE^ CENTS . VOL. XLU., NO. 296. (Classified Advertising on Page 16) MAI^CHESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, 1928. (EIGHTEEN PAGES) “ ICE BOX BANDITS” The Hoovers Gr€0t the Returning Coolidges WERE SEEN BY MANY Green Death Car Traced G.O.P. LEADERS From Springfield to Place I ^ y e s TraO of Death, De* IN CONFERENCE Police vastation and Sitfering in Where It Was Found a Wake— Properly Loss Set Wrecked. ONNEWPLANS Albany to I t At Three Millions— Thou Willimantic, Sept. 14.— The trial Poughkeepsie, N. Y., Sept. 14.— Dr. Chester A. Roig, Pough- ^ of the “ Ice Box Bandits” as Spring- Hoover^ Curtis and . Work Denying cnarges that he is guilty of keepsie veterinarian, examined sands Homeless as Whole cruelty in allowing his German field calls Albert J. Raymond and “ LucKy” last night and issued a Talk About New England police dog “ Lucky” to essay a 153- statement that the canine was 1% Roland G. Lalone, the Worcester, mile swim from Albany to New normal physical condition after Villages are Wiped Out— Mass., youths charged with mur YorK, John Schweighart, of 3425 covering 59-nauticai miles from Al dering State Policeman Irving H. States— Roraback Named Bayebester avenue, New YorK, de bany to Poughkeepsie in the ex Coasts S tr ^ n W i t h clared this morning that he expect Nelson, of Now Haven, at Pomfret ceptionally fast time of 23 hours Chairman of Committee. -

Senators Win Title, 4–3

The Library of America • Story of the Week From The Great American Sports Page: A Century of Classic Columns (Library of America, 2019), pages 15–21. Originally published in The New York Herald Tribune (October 11, 1924). GRANTLAND RICE Even if Grantland Rice’s name means nothing to you, it’s entirely pos- sible you have heard someone utter something about the four horse- men of a football apocalypse “outlined against a blue-gray October sky.” They are arguably the most famous and certainly the most quoted words in sportswriting history. Rice (1880–1954) wrote them as he piled on adjectives and imagery to describe Notre Dame’s backfield running amok against poor Army in 1924. The unofficial leader of the press box’s Gee-Whiz contingent, he seemed to see every event he covered as the equivalent of the Trojan War. Some contemporaries mocked him and subsequent generations of sportswriters were even harsher. But Rice, the star of the New York Herald Tribune’s sports page and a nationally syndicated columnist during the Roaring Twenties and the Depression, never stopped striving to paint word pictures for audiences in the age before TV. He was best when he took some of the purple out of his prose the way he did in the following story about a once-dominant pitcher recapturing greatness in the ’24 World Series. Rice remained true to his vision of sports until the end. When he died, he did it the only place he could—at his typewriter. HHH Senators Win Title, 4–3 ESTINY, WAITING for the final curtain, stepped from the wings today D and handed the king his crown. -

1962 Minnesota Twins Media Guide

MINNESOTA TWINS METROPOLITAN STADIUM - BLOOMINGTON, MINNESOTA /eepreieniin the AMERICAN LEAGUE __flfl I/ic Upper l?ic/we1 The Name... The name of this baseball club is Minnesota Twins. It is unique, as the only major league baseball team named after a state instead of a city. The reason unlike all other teams, this one represents more than one city. It, in fact, represents a state and a region, Minnesota and the Upper Midwest, in the American League. A survey last year drama- tized the vastness of the Minnesota Twins market with the revelation that up to 47 per cent of the fans at weekend games came from beyond the metropolitan area surrounding the stadium. The nickname, Twins, is in honor of the two largest cities in the Upper Midwest, the Twin Cities of Minne- apolis and St. Paul. The Place... The home stadium of the Twins is Metropolitan Stadium, located in Bloomington, the fourth largest city in the state of Minnesota. Bloomington's popu- lation is in excess of 50,000. Bloomington is in Hen- nepin County and the stadium is approximately 10 miles from the hearts of Minneapolis (Hennepin County) and St. Paul (Ramsey County). Bloomington has no common boundary with either of the Twin Cities. Club Records Because of the transfer of the old Washington Senators to Minnesota in October, 1960, and the creation of a completely new franchise in the Na- tion's Capital, there has been some confusion over the listing of All-Time Club records. In this booklet, All-Time Club records include those of the Wash- ington American League Baseball Club from 1901 through 1960, and those of the 1961 Minnesota Twins, a continuation of the Washington American League Baseball Club.