View Preprint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cone Collector N°23

THE CONE COLLECTOR #23 October 2013 THE Note from CONE the Editor COLLECTOR Dear friends, Editor The Cone scene is moving fast, with new papers being pub- António Monteiro lished on a regular basis, many of them containing descrip- tions of new species or studies of complex groups of species that Layout have baffled us for many years. A couple of books are also in André Poremski the making and they should prove of great interest to anyone Contributors interested in Cones. David P. Berschauer Pierre Escoubas Our bulletin aims at keeping everybody informed of the latest William J. Fenzan developments in the area, keeping a record of newly published R. Michael Filmer taxa and presenting our readers a wide range of articles with Michel Jolivet much and often exciting information. As always, I thank our Bernardino Monteiro many friends who contribute with texts, photos, information, Leo G. Ros comments, etc., helping us to make each new number so inter- Benito José Muñoz Sánchez David Touitou esting and valuable. Allan Vargas Jordy Wendriks The 3rd International Cone Meeting is also on the move. Do Alessandro Zanzi remember to mark it in your diaries for September 2014 (defi- nite date still to be announced) and to plan your trip to Ma- drid. This new event will undoubtedly be a huge success, just like the two former meetings in Stuttgart and La Rochelle. You will enjoy it and of course your presence is indispensable! For now, enjoy the new issue of TCC and be sure to let us have your opinions, views, comments, criticism… and even praise, if you feel so inclined. -

BAST1986050004005.Pdf

BASTERIA, 50: 93-150, 1986 Alphabetical revision of the (sub)species in recent Conidae. 9. ebraeus to extraordinarius with the description of Conus elegans ramalhoi, nov. subspecies H.E. Coomans R.G. Moolenbeek& E. Wils Institute of Taxonomic Zoology (Zoological Museum) University of Amsterdam INTRODUCTION In this ninth part of the revision all names of recent Conus taxa beginning with the letter e are discussed. Amongst these are several nominal species of tent-cones with a C.of close-set lines, the shell a darker pattern consisting very giving appearance (e.g. C. C. The elisae, euetrios, eumitus). phenomenon was also mentioned for C. castaneo- fasciatus, C. cholmondeleyi and C. dactylosus in former issues. This occurs in populations where with normal also that consider them specimens a tent-pattern are found, so we as colour formae. The effect is known shells in which of white opposite too, areas are present, leaving 'islands' with the tent-pattern (e.g. C. bitleri, C. castrensis, C. concatenatus and C. episco- These colour formae. patus). are also art. Because of a change in the rules of the ICZN (3rd edition, 1985: 73-74), there has risen a disagreement about the concept of the "type series". In cases where a museum type-lot consists of more than one specimen, although the original author(s) did not indicate that more than one shell was used for the description, we will designate the single originally mentioned and/or figured specimen as the "lectotype". Never- theless a number of taxonomists will consider that "lectotype" as the holotype, and disregard the remaining shells in the lot as type material. -

22 April 2013 the Note from CONE the Editor COLLECTOR Dear Friends

THE CONE COLLECTOR #22 April 2013 THE Note from CONE the Editor COLLECTOR Dear friends, Editor The project “The Cone Collector” is still under seven years old António Monteiro and yet when I look at all we have achieved so far I cannot help thinking that we have probably exceeded expectations. Layout André Poremski We started modestly – as becomes any serious project – back in Contributors October 2006, with our newsletter aimed at all those who are Carlos Afonso interested in studying or collecting Cones, from professional Jim Cootes biologists to amateur collectors. Today we can proudly display Remy Devorsine a total of twenty-four numbers of TCC, two hugely successful Sébastien Dutertre international meetings and a website that brings together an Günther Herndl unparalleled wealth of information on Cones. Joaquin M. Inchaustegui Bruce Livett As a matter of fact, after the uploading in our website (at www. Philippe Quiquandon Christopher Roux theconecollector.com ) of the important and vastly updated Manuel Jiménez Tenorio and augmented work by Mike Filmer’s involving taxonomy and Will van Damme nomenclature, we now have at the same address Paul Kersten’s Alessandro Zanzi extremely useful and well-known Checklist, enriched with new images and much more detailed information than before. This is the work of a team – the names of Manuel Jimenez Tenorio, Bill Fenzan, John Tucker, Gavin Malcolm, Mike Filmer, Paul Kersten and André Poremski readily come to my mind as front row collaborators of TCC, but all others who have contributed with articles, photos, opinions, suggestions and unfailing support deserve equal credit! The project belongs to all and can only survive with the continued support of all. -

The Hawaiian Species of Conus (Mollusca: Gastropoda)1

The Hawaiian Species of Conus (Mollusca: Gastropoda) 1 ALAN J. KOHN2 IN THECOURSE OF a comparative ecological currents are factors which could plausibly study of gastropod mollus ks of the genus effect the isolation necessary for geographic Conus in Hawaii (Ko hn, 1959), some 2,400 speciation . specimens of 25 species were examined. Un Of the 33 species of Conus considered in certainty ofthe correct names to be applied to this paper to be valid constituents of the some of these species prompted the taxo Hawaiian fauna, about 20 occur in shallow nomic study reported here. Many workers water on marine benches and coral reefs and have contributed to the systematics of the in bays. Of these, only one species, C. ab genus Conus; nevertheless, both nomencla breviatusReeve, is considered to be endemic to torial and biological questions have persisted the Hawaiian archipelago . Less is known of concerning the correct names of a number of the species more characteristic of deeper water species that occur in the Hawaiian archi habitats. Some, known at present only from pelago, here considered to extend from Kure dredging? about the Hawaiian Islands, may (Ocean) Island (28.25° N. , 178.26° W.) to the in the future prove to occur elsewhere as island of Hawaii (20.00° N. , 155.30° W.). well, when adequate sampling methods are extended to other parts of the Indo-West FAUNAL AFFINITY Pacific region. As is characteristic of the marine fauna of ECOLOGY the Hawaiian Islands, the affinities of Conus are with the Indo-Pacific center of distribu Since the ecology of Conus has been dis tion . -

Biogeography of Coral Reef Shore Gastropods in the Philippines

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274311543 Biogeography of Coral Reef Shore Gastropods in the Philippines Thesis · April 2004 CITATIONS READS 0 100 1 author: Benjamin Vallejo University of the Philippines Diliman 28 PUBLICATIONS 88 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: History of Philippine Science in the colonial period View project Available from: Benjamin Vallejo Retrieved on: 10 November 2016 Biogeography of Coral Reef Shore Gastropods in the Philippines Thesis submitted by Benjamin VALLEJO, JR, B.Sc (UPV, Philippines), M.Sc. (UPD, Philippines) in September 2003 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Marine Biology within the School of Marine Biology and Aquaculture James Cook University ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to describe the distribution of coral reef and shore gastropods in the Philippines, using the species rich taxa, Nerita, Clypeomorus, Muricidae, Littorinidae, Conus and Oliva. These taxa represent the major gastropod groups in the intertidal and shallow water ecosystems of the Philippines. This distribution is described with reference to the McManus (1985) basin isolation hypothesis of species diversity in Southeast Asia. I examine species-area relationships, range sizes and shapes, major ecological factors that may affect these relationships and ranges, and a phylogeny of one taxon. Range shape and orientation is largely determined by geography. Large ranges are typical of mid-intertidal herbivorous species. Triangualar shaped or narrow ranges are typical of carnivorous taxa. Narrow, overlapping distributions are more common in the central Philippines. The frequency of range sizesin the Philippines has the right skew typical of tropical high diversity systems. -

THE LISTING of PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T

August 2017 Guido T. Poppe A LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS - V1.00 THE LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T. Poppe INTRODUCTION The publication of Philippine Marine Mollusks, Volumes 1 to 4 has been a revelation to the conchological community. Apart from being the delight of collectors, the PMM started a new way of layout and publishing - followed today by many authors. Internet technology has allowed more than 50 experts worldwide to work on the collection that forms the base of the 4 PMM books. This expertise, together with modern means of identification has allowed a quality in determinations which is unique in books covering a geographical area. Our Volume 1 was published only 9 years ago: in 2008. Since that time “a lot” has changed. Finally, after almost two decades, the digital world has been embraced by the scientific community, and a new generation of young scientists appeared, well acquainted with text processors, internet communication and digital photographic skills. Museums all over the planet start putting the holotypes online – a still ongoing process – which saves taxonomists from huge confusion and “guessing” about how animals look like. Initiatives as Biodiversity Heritage Library made accessible huge libraries to many thousands of biologists who, without that, were not able to publish properly. The process of all these technological revolutions is ongoing and improves taxonomy and nomenclature in a way which is unprecedented. All this caused an acceleration in the nomenclatural field: both in quantity and in quality of expertise and fieldwork. The above changes are not without huge problematics. Many studies are carried out on the wide diversity of these problems and even books are written on the subject. -

CONE SHELLS - CONIDAE MNHN Koumac 2018

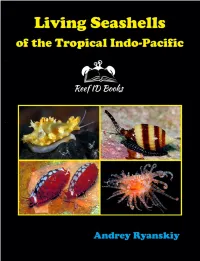

Living Seashells of the Tropical Indo-Pacific Photographic guide with 1500+ species covered Andrey Ryanskiy INTRODUCTION, COPYRIGHT, ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INTRODUCTION Seashell or sea shells are the hard exoskeleton of mollusks such as snails, clams, chitons. For most people, acquaintance with mollusks began with empty shells. These shells often delight the eye with a variety of shapes and colors. Conchology studies the mollusk shells and this science dates back to the 17th century. However, modern science - malacology is the study of mollusks as whole organisms. Today more and more people are interacting with ocean - divers, snorkelers, beach goers - all of them often find in the seas not empty shells, but live mollusks - living shells, whose appearance is significantly different from museum specimens. This book serves as a tool for identifying such animals. The book covers the region from the Red Sea to Hawaii, Marshall Islands and Guam. Inside the book: • Photographs of 1500+ species, including one hundred cowries (Cypraeidae) and more than one hundred twenty allied cowries (Ovulidae) of the region; • Live photo of hundreds of species have never before appeared in field guides or popular books; • Convenient pictorial guide at the beginning and index at the end of the book ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The significant part of photographs in this book were made by Jeanette Johnson and Scott Johnson during the decades of diving and exploring the beautiful reefs of Indo-Pacific from Indonesia and Philippines to Hawaii and Solomons. They provided to readers not only the great photos but also in-depth knowledge of the fascinating world of living seashells. Sincere thanks to Philippe Bouchet, National Museum of Natural History (Paris), for inviting the author to participate in the La Planete Revisitee expedition program and permission to use some of the NMNH photos. -

Some Economically Important Bivalves and Gastropods Found in the Island of Hadji Panglima Tahil, in the Province of Sulu, Philippines

International Research Journal of Biological Sciences ___________________________________ ISSN 2278-3202 Vol. 2(7), 30-36, July (2013) Int. Res. J. Biological Sci. Some Economically Important Bivalves and Gastropods found in the Island of Hadji Panglima Tahil, in the province of Sulu, Philippines Sharon Rose M. Tabugo 1, Jocelyn O. Pattuinan 1, Nathanie Joy J. Sespene 1 and Aldren J. Jamasali 2 1Department of Biological Sciences,College of Science and Mathematics, MSU-Iligan Institute of Technology, Iligan City 2Mindanao State University- Jolo, SULU Available online at: www.isca.in Received 17th April 2013, revised 26 th April 2013, accepted 4th May 2013 Abstract The Philippines is a haven of a rich diversity of marine organisms. Unraveling this diversity had posed a tremendous challenge. The existing security threat in some areas of the archipelago had led to a dearth of information with regard to the diversity of organisms especially the islands located in the province of Sulu. Marine mollusc studies are still among those that are overseen by many researchers. To date, there is still a lack of basic information such as diversity and species checklist that make it impossible to assess the rate of population lost among existing marine molluscs. There is no published information on the actual number of marine shelled molluscan species in the area. This work assessed, described and identified some economically important molluscs in the island of Hadji Panglima Tahil, in the province of Sulu, Philippines. There were a total of 18 molluscs (marine bivalves & gastropods) species found and identified in the island. The molluscs served as food, ornaments and as source of livelihood by residents in the area, which is separated by sea from Jolo, the capital municipality of the province. -

Radular Morphology of Conus (Gastropoda: Caenogastropoda: Conidae) from India

Molluscan Research 27(3): 111–122 ISSN 1323-5818 http://www.mapress.com/mr/ Magnolia Press Radular morphology of Conus (Gastropoda: Caenogastropoda: Conidae) from India J. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, 1, 3 S. ANTONY FERNANDO, 1 B. A. CHALKE, 2 K. S. KRISHNAN. 2, 3* 1.Centre of Advanced Study in Marine Biology, Annamalai University, Parangipettai-608 502, Cuddalore, Tamilnadu, India. 2.Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Homi Bhabha Road, Colaba, Mumbai-400 005, India. 3.National Centre for Biological Sciences, TIFR, Old Bellary Road, Bangalore-560 065, India.* Corresponding author E-mail: (K. S. Krishnan): [email protected]. Abstract Radular morphologies of 22 species of the genus Conus from Indian coastal waters were analyzed by optical and scanning elec- tron microscopy. Although the majority of species in the present study are vermivorous, all three feeding modes known to occur in the genus are represented. Specific radular-tooth structures consistently define feeding modes. Species showing simi- lar feeding modes also show fine differences in radular structures. We propose that these structures will be of value in species identification in cases of ambiguity in other characteristics. Examination of eight discrete radular-tooth components has allowed us to classify the studied species of Conus into three groups. We see much greater inter-specific differences amongst vermivorous than amongst molluscivorous and piscivorous species. We have used these differences to provide a formula for species identification. The radular teeth of Conus araneosus, C. augur, C. bayani, C. biliosus, C. hyaena, C. lentiginosus, C. loroisii, and C. malacanus are illustrated for the first time. In a few cases our study has also enabled the correction of some erroneous descriptions in the literature. -

12 - October 2009 the Note from CONE the Editor

THE CONE COLLECTOR #12 - October 2009 THE Note from CONE the editor COLLECTOR It is always a renewed pleasure to put together another issue of Th e Cone Collector. Th anks to many contributors, we have managed so far to stick to the set schedule – André’s eff orts are greatly to be Editor praised, because he really does a great graphic job from the raw ma- António Monteiro terial I send him – and, I hope, to present in each issue a wide array of articles that may interest our many readers. Remember we aim Layout to present something for everybody, from beginners in the ways of André Poremski Cone collecting to advanced collectors and even professional mala- cologists! Contributors Randy Allamand In the following pages you will fi nd the most recent news concern- Kathleen Cecala ing new publications, new taxa, rare species, interesting or outstand- Ashley Chadwick ing fi ndings, and many other articles on every aspect of the study Paul Kersten and collection of Cones (and their relationship to Mankind), as well Gavin Malcolm as the ever popular section “Who’s Who in Cones” that helps to get Baldomero Olivera Toto Olivera to know one another better! Alexander Medvedev Donald Moody You will also fi nd a number of comments, additions and corrections Philippe Quiquandon to our previous issue. Keep them coming! Th ese comments are al- Jon Singleton ways extremely useful to everybody. Don’t forget that Th e Cone Col- lector is a good place to ask any questions you may have concerning the identifi cation of any doubtful specimens in your collections, as everybody is always willing to express an opinion. -

Benthic Habitats and Biodiversity of Dampier and Montebello Marine

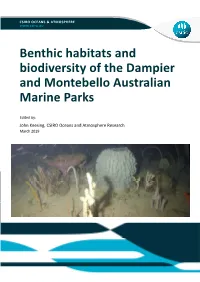

CSIRO OCEANS & ATMOSPHERE Benthic habitats and biodiversity of the Dampier and Montebello Australian Marine Parks Edited by: John Keesing, CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere Research March 2019 ISBN 978-1-4863-1225-2 Print 978-1-4863-1226-9 On-line Contributors The following people contributed to this study. Affiliation is CSIRO unless otherwise stated. WAM = Western Australia Museum, MV = Museum of Victoria, DPIRD = Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Study design and operational execution: John Keesing, Nick Mortimer, Stephen Newman (DPIRD), Roland Pitcher, Keith Sainsbury (SainsSolutions), Joanna Strzelecki, Corey Wakefield (DPIRD), John Wakeford (Fishing Untangled), Alan Williams Field work: Belinda Alvarez, Dion Boddington (DPIRD), Monika Bryce, Susan Cheers, Brett Chrisafulli (DPIRD), Frances Cooke, Frank Coman, Christopher Dowling (DPIRD), Gary Fry, Cristiano Giordani (Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia), Alastair Graham, Mark Green, Qingxi Han (Ningbo University, China), John Keesing, Peter Karuso (Macquarie University), Matt Lansdell, Maylene Loo, Hector Lozano‐Montes, Huabin Mao (Chinese Academy of Sciences), Margaret Miller, Nick Mortimer, James McLaughlin, Amy Nau, Kate Naughton (MV), Tracee Nguyen, Camilla Novaglio, John Pogonoski, Keith Sainsbury (SainsSolutions), Craig Skepper (DPIRD), Joanna Strzelecki, Tonya Van Der Velde, Alan Williams Taxonomy and contributions to Chapter 4: Belinda Alvarez, Sharon Appleyard, Monika Bryce, Alastair Graham, Qingxi Han (Ningbo University, China), Glad Hansen (WAM), -

(Gastropods and Bivalves) and Notes on Environmental Conditions of Two

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2014; 2 (5): 72-90 ISSN 2320-7078 The molluscan fauna (gastropods and bivalves) JEZS 2014; 2 (5): 72-90 © 2014 JEZS and notes on environmental conditions of two Received: 24-08-2014 Accepted: 19-09-2014 adjoining protected bays in Puerto Princesa City, Rafael M. Picardal Palawan, Philippines College of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, Western Philippines University Rafael M. Picardal and Roger G. Dolorosa Roger G. Dolorosa Abstract College of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, Western Philippines With the rising pressure of urbanization to biodiversity, this study aimed to obtain baseline information University on species richness of gastropods and bivalves in two protected bays (Turtle and Binunsalian) in Puerto Princesa City, Philippines before the establishment of the proposed mega resort facilities. A total of 108 species were recorded, (19 bivalves and 89 gastropods). The list includes two rare miters, seven recently described species and first record of Timoclea imbricata (Veneridae) in Palawan. Threatened species were not encountered during the survey suggesting that both bays had been overfished. Turtle Bay had very low visibility, low coral cover, substantial signs of ecosystem disturbances and shift from coral to algal communities. Although Binunsalian Bay had clearer waters and relatively high coral cover, associated fish and macrobenthic invertebrates were of low or no commercial values. Upon the establishment and operations of the resort facilities, follow-up species inventories and habitat assessment are suggested to evaluate the importance of private resorts in biodiversity restoration. Keywords: Binunsalian Bay, bivalves, gastropods, Palawan, species inventory, Turtle Bay 1. Introduction Gastropods and bivalves are among the most fascinating groups of molluscs that for centuries have attracted hobbyists, businessmen, ecologists and scientists among others from around the globe.