Kwir Megi En Aye Bimoko

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Foreign Policy Determined by Sitting Presidents: a Case

T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI ANKARA, 2019 T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI SUPERVISOR Prof. Dr. Çınar ÖZEN ANKARA, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ i ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... iv FIGURES ................................................................................................................... vi PHOTOS ................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE UGANDA’S JOURNEY TO AUTONOMY AND CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM I. A COLONIAL BACKGROUND OF UGANDA ............................................... 23 A. Colonial-Background of Uganda ...................................................................... 23 B. British Colonial Interests .................................................................................. 32 a. British Economic Interests ......................................................................... -

Conclusion: an End to Conflict

Conclusion: an end to conflict Looking back on their daily lives over the last 40 years or so, the majority of Uganda's citizens will reflect on the turbulence of the times they have lived through. In some respects, there has been little change in the patterns of daily life for millions of Ugandans. People continue to cultivate the land by hand, or to herd their animals in ways that have barely altered since Uganda was created a hundred years ago. They continue to provide for their own subsistence, with relatively little contact with external markets. This sense of continuity was captured by Lorochom, the Karimojong elder, who explained, 'Governments change and the weather changes... but we continue herding our animals.' There have been some positive changes, however. The mismanagement of Uganda's economy under the regimes of Idi Amin and Obote II left Uganda amongst the poorest countries in the world. Improved management of the national economy has been one of the great achievements of the NRM and, provided that • Margaret Muhindo in her aid flows do not significantly diminish, Ugandans can kitchen garden. In a good reasonably look forward to continued economic growth, better public year, she will be able to sell surplus vegetables for cash. services, and further investments in essential infrastructure. In a bad year, she and her Nonetheless, turbulence has been the defining feature of the age, family will scrape by on the and it is in the political realm that turbulence has been profoundly food they grow. destructive. Instead of protecting the lives and property of its citizens, the state in one form or other has been responsible for the murder, torture, harassment, displacement, and impoverishment of its people. -

Amin: His Seizure and Rule in Uganda. James Francis Hanlon University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1974 Amin: his seizure and rule in Uganda. James Francis Hanlon University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Hanlon, James Francis, "Amin: his seizure and rule in Uganda." (1974). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2464. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2464 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMIN: HIS SEIZURE AND RULE IN UGANDA A Thesis Presented By James Francis Hanlon Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS July 1974 Major Subject — Political Science AMIN: HIS SEIZURE AND RULE IN UGANDA A Thesis Presented By James Francis Hanlon Approved as to style and content by: Pro i . Edward E. Feit. Chairman of Committee Prof. Michael Ford, member ^ Prof. Ferenc Vali, Member /£ S J \ Dr. Glen Gordon, Chairman, Department of Political Science July 1974 CONTENTS Introduction I. Uganda: Physical History II. Ethnic Groups III. Society: Its Constituent Parts IV. Bureaucrats With Weapons A. Police B . Army V. Search For Unity A. Buganda vs, Ohote B. Ideology and Force vi. ArmPiglti^edhyithe-.Jiiternet Archive VII. Politics Without lil3 r 2Qj 5 (1970-72) VIII. Politics and Foreign Affairs IX. Politics of Amin: 1973-74 C one ius i on https://archive.org/details/aminhisseizureruOOhanl , INTRODUCTION The following is an exposition of Edward. -

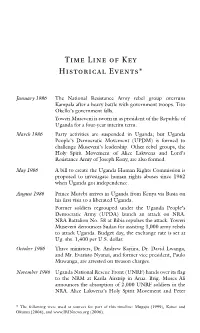

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006). -

Uganda: No Resolution to Growing Tensions

UGANDA: NO RESOLUTION TO GROWING TENSIONS Africa Report N°187 – 5 April 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. UNRESOLVED ISSUES OF NATIONAL INTEGRATION ....................................... 2 A. THE PERSISTENCE OF ETHNIC, REGIONAL AND RELIGIOUS DIVISIONS .......................................... 2 B. POST-INDEPENDENCE POLICIES .................................................................................................... 3 1. Obote and the UPC ...................................................................................................................... 3 2. Amin and military rule ................................................................................................................. 4 3. The interim period ........................................................................................................................ 5 4. Obote and the UPC again ............................................................................................................. 5 III. LEGACIES OF THE NRA INSURGENCY ................................................................... 6 A. NO-PARTY RULE ......................................................................................................................... 6 B. THE SHIFT TO PATRONAGE AND PERSONAL RULE ....................................................................... -

Crisis of Legitimacy and Political Violence in Uganda, 1890 to 1979

AFRICAN HISTORIES AND MODERNITIES CRISIS OF LEGITIMACY AND POLITICAL VIOLENCE IN UGANDA, 1890 TO 1979 Ogenga Otunnu African Histories and Modernities Series Editors Toyin Falola The University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas, USA Matthew M. Heaton Virginia Tech Blacksburg, USA This book series serves as a scholarly forum on African contributions to and negotiations of diverse modernities over time and space, with a partic- ular emphasis on historical developments. Specifically, it aims to refute the hegemonic conception of a singular modernity, Western in origin, spread- ing out to encompass the globe over the last several decades. Indeed, rather than reinforcing conceptual boundaries or parameters, the series instead looks to receive and respond to changing perspectives on an important but inherently nebulous idea, deliberately creating a space in which multiple modernities can interact, overlap, and conflict. While privileging works that emphasize historical change over time, the series will also feature scholar- ship that blurs the lines between the historical and the contemporary, rec- ognizing the ways in which our changing understandings of modernity in the present have the capacity to affect the way we think about African and global histories. Editorial Board Aderonke Adesanya, Art History, James Madison University Kwabena Akurang-Parry, History, Shippensburg University Samuel O. Oloruntoba, History, University of North Carolina, Wilmington Tyler Fleming, History, University of Louisville Barbara Harlow, English and Comparative -

A Historical Analysis of the Impact of the 1966 Ugandan Constitutional Crisis on Buganda’S Monarchy

A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF THE IMPACT OF THE 1966 UGANDAN CONSTITUTIONAL CRISIS ON BUGANDA’S MONARCHY by Fred Musisi Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Philosophiae Doctor in The Faculty of Arts at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Promoter: Dr R.O. Herbst (NMMU) Co- Promoter: Professor P. Cunningham (NMMU) 2017 DECLARATION NAME: Fred Musisi STUDENT NUMBER: 211062847 QUALIFICATION: Philosophiae Doctor TITLE OF PROJECT: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF THE IMPACT OF THE 1966 UGANDAN CONSTITUTIONAL CRISIS ON BUGANDA’S MONARCHY In accordance with Rule G4.6.3, I hereby declare that the above-mentioned thesis is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. ……………………………………….. SIGNATURE DATE: 2017 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this thesis is owed to the insightful help and direction of various people who provided encouragement and love. I am greatly indebted to Dr. R. O. Herbst, my Promoter for his professional guidance, motivation and dedication in pursing this study and eventual writing of the thesis. I would like in a special way thank my Co-Promoter Professor P. Cunningham whose continuous encouragement gave me immeasurable impetus to complete this study. Without the steadfast support of my Promoters this research would not have materialised. This thesis therefore represents almost as much the culmination of their hard work and energy as well as mine. I also wish to thank my family: My wife, Allen Musisi and children; Matovu Nathan, Sserugga Elijah and Namatovu Nicole who for the purpose of pursuing the Ph.D. -

Taylor.Edgar-2015 Word Copy

Asians and Africans in Ugandan Urban Life, 1959-1972 by Edgar Curtis Taylor A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor Derek R. Peterson, Co-Chair Professor Nancy Rose Hunt, Co-Chair Professor Kelly M. Askew Professor Nakanyike B. Musisi, University of Toronto Professor Mrinalini Sinha © Edgar Curtis Taylor 2016 Dedication For Harold and Addie ii Acknowledgements There are few greater lessons in human generosity and the collective nature of knowledge than those that come from writing a dissertation. It seems inappropriate here to refer to accumulated “debts,” a word that implies a set of quantifiable obligations inscribed in a ledger book – though there may be some of those as well. I have been enriched by interactions, exchanges, and friendships that make the composition of an acknowledgements section both daunting and gratifying. As the usual disclaimer goes, no one but myself should be held responsible for this dissertation, but whatever insights it contains would not have been possible without each of the people mentioned here and in the bibliography. I apologize in advance for any omissions, which are surely as numerous as they are unintentional. I have been extremely fortunate to benefit from the generosity of time, insight, and enthusiasm of my co-chairs, to whom I am deeply grateful. Derek Peterson came to Michigan in 2009 and immediately introduced me to a craft of historical analysis and a rigor of research equal parts exacting, exciting, and enriching. In Michigan and in Uganda, I have benefited not only from his intellectual guidance and encouragement but also from his commitment to strengthening institutions of historical research for all in numerous ways (not least of which has been preserving iii and cataloging several of the archival collections used in this study). -

The Effect of School Closure On

Re-examining Uganda’s 1966 Crisis: The Uganda People’s Congress and the Congo Rebellion by Cory James Peter Scott B.A., University of Victoria, 2006 Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Cory James Peter Scott 2013 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2013 Approval Name: Cory James Peter Scott Degree: Master of Arts (History) Title of Thesis: Re-examing Uganda’s 1966 Crisis: The Uganda People’s Congress and the Congo Rebellion Examining Committee: Chair: Roxanne Panchasi Associate Professor Thomas Kuehn Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Ilya Vinkovetsky Supervisor Associate Professor Aaron Windel External Examiner Limited Term Instructor, Department of History Simon Fraser University Date Defended/Approved: May 10, 2013 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract Historians of Uganda have generally viewed the 1966 Crisis in Uganda as an inevitable clash between two opposing forces, the Uganda People's Congress national government and the government of the Kingdom of Buganda, trying to settle colonial-era rivalries in the post-independence era. As such, these authors focus solely on internal causes for the 1966 Crisis and fail to consider the impact of Uganda’s regional and international relations on politics within the country. This thesis argues that the 1966 Crisis can only be understood in the context of Uganda’s new and complex international relations after independence, particularly the consequences of the UPC’s intervention in the Congo Rebellion from 1964 to 1965. It will consider how the government of Uganda’s participation in the Congo Rebellion was aided by Uganda’s new relations with the outside world, and how this intervention in turn destabilized politics within Uganda and prompted Obote’s coup d’état on 15 April 1966. -

Arab-Israel Rivalry for Support in Black Africa

^ARAB-ISRAEL RIVALRY FOR SUPPORT IN BLACK AFRICA: THE CASE OF EAST AFRICA, 1961 - 1971 By Taher lAbed Submitted in Fullfilment of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Arts. Department of Government University of Nairobi ( 1987 ) DECLARATION This Thesis is my original work and has not been presented for examination to any other university. This Thesis has been submitted to the University of Nairobi with my approval. Ill ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This work was undertaken when I was a full time I Charged Fare of the Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia in Nairobi. I had to work mostly on weekends, during holidays and evenings. It is however, not possible to acknowledge all the people who gave me intellectual and moral assistance. I am most grateful to Dr. Nicholas Nyangira of the Department of Government. He gave me intellectual inspiration, sitting with me over lengthy hours and advising me on virtually all the structure, content, and theoretical frame work of the thesis. Special appreciation goes to Professor El Masri of the Linguistic Department for his encouragement and at times his translation of key concepts from Arabic into English. I am also grateful to Professor I. Salim of the Department of History for both moral and intellectual support especially for his help on Afro-Arab relations. In many and long hours I spent reading and research ing on the thesis topic, I benefited from many organiza tions and individuals, many of whom cannot be enumerated here. However, special mention must go to the University IV of Nairobi Library staff who assisted me in locating relevant journals, books and other materials that I needed. -

Uganda: the Marginalization T of Minorities the MARGINALIZATION of MINORITIES the MARGINALIZATION • UGANDA: an MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT an MRG INTERNATIONAL

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Uganda: The Marginalization T of Minorities THE MARGINALIZATION OF MINORITIES THE MARGINALIZATION • UGANDA: AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY WAIRAMA G. BAKER UGANDA: THE MARGINALIZATION Acknowledgements OF MINORITIES Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully acknowledges the support of the Scottish Catholic © Minority Rights Group International 2001 International Aid Fund (SCIAF) and all the organizations All rights reserved. and individuals who gave financial and other assistance for Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or for this Report. other non-commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any This Report has been commissioned and is published by form for commercial purposes without the prior express permission of the MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the issue copyright holders. which forms its subject. The text and views of the author do For further information please contact MRG. not necessarily represent, in every detail and in all its A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British aspects, the collective view of MRG. Library. MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert read- ISBN 1 897 693 192 ers who contributed to this Report, in particular Tadesse ISSN 0305 6252 Tafesse (Programme Coordinator) and Katrina Payne Published December 2001 (Reports Editor). Typeset by Texture Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. THE AUTHOR DR WAIRAMA G. BAKER is an advocate and legal con- sultant, and a lecturer in law at Makerere University in Uganda. He is currently the Programme Manager of the Interdisciplinary Teaching of Human Rights, Peace and Ethics at the Human Rights and Peace Centre (HURIPEC) at Makerere University.