Narrative Change in Professional Wrestling: Audience Address and Creative Authority in the Era of Smart Fans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samoan Submission Machines

Samoan Submission Machines: Grappling with Representations of Samoan Identity in Professional Wrestling Theo Plothe1 Savannah State University [email protected] Amongst the myriad of characters to step foot in the squared circle, perhaps no ethnic group has been as celebrated or marginalized as the Samoans who have made their names in professional wrestling. The discussion of Samoan identity in the context of sport has examined Maori identity and masculinity in New Zealand, among other topics, but there has yet to be work which considers Samoans within professional wrestling. This research investigates Samoan identity through a content analysis of televised wrestling matches. This research identifies six primary stereotypes under which Samoan identity is portrayed. These portrayals of Samoan characters, I argue, flatten the representation of this ethnic group within wrestling and culture at large. Keywords: Samoans, identity, representation, gimmicks Introduction Among the myriad of characters to step foot in the squared circle, perhaps no ethnic group has been as celebrated or marginalized as the Samoans who have made their names in professional wrestling. This research investigates the identity of Samoans within professional wrestling, and the different ways they are constructed and presented to audiences. “Gimmicks,” characters portrayed by a wrestler “resulting in the sum of fictional elements, attire and wrestling ability” (Oliva and Calleja 3) utilized by Samoans have run the gamut from the wild uncivilized savage, to the sumo (both in villainous Japanese and comically absurd iterations), to the ultra-cool mogul who wears silk shirts and fancy shoes. Their ability to cut promos, an important facet of the modern gimmick allowing wrestlers to address their opponents and storylines, varies widely as well, but all lie within their Samoan identity. -

The Cord Weekly (November 19, 1992)

THE CORD A WILFRID LAURIER UNIVERSITY STUDENT PUBLICATION VOLUME XXXIII ISSUE 14 NOVEMBER 19 1992 Second Cup gets Champions. the support of over 3000 staff and students few weeks. The current total of Lianne Jewitt by has signatures on both petitions The Second Cup, favoured reached over 3000. and among students, faculty, When asked to comment on staff alike is scheduled to be re- the petitions, Rayner said that he as of December 11, 1992; placed "hasn't seen the petitions." Rayner a petition is being circulated in also said that "we'll consider the or them response to this aspects action. (the petitions)". Director of Exactly what Personnel and The current number will be consider- Administrative ed is uncertain, as Services, Earl Rayner clearly of on signatures states Rayner, said the that the Second reason for re- Cup was of the given a "one placement both petitions has year Second Cup is trial basis", and that it is "costing the decision for their dismissal us too much reached over 3000. "made money to havfc it was this there." Rayner past September." The Lady Soccer Hanks wwn—i the iliwnto, McMaater, St. Mary's, and McQIII, added, "the return It was the Second title. and return to Laurlor aHh the National Cluaipto—tUp - ■ I D<lfc gTOarGO If®** VVGRMfI to the university is hardly cover- Cup's one year anniversary on ing our costs." campus. Rayner has not mentioned WLU student confesses Quite clearly, coffee and hot what will be the replacing popu- chocolate drinkers, and cookie lar coffee cart, but concerned coffee drinkers fear it to in bomb threat campus and muffin eaters' main concern calling will be a university-run establish- with the pending absence of the ment Second Cup is the lack of quality "I think it's terrorism, and certainly deserving of Dean of Student's Pat Brethour secretary, that awaits if a university run ser- by charges," said Fred Nichols, Dean of Students. -

The Popular Culture Studies Journal

THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 2018 Editor NORMA JONES Liquid Flicks Media, Inc./IXMachine Managing Editor JULIA LARGENT McPherson College Assistant Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY Mid-America Christian University Copy Editor Kevin Calcamp Queens University of Charlotte Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON Indiana State University Assistant Reviews Editor JESSICA BENHAM University of Pittsburgh Please visit the PCSJ at: http://mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture- studies-journal/ The Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. Copyright © 2018 Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 Cover credit: Cover Artwork: “Wrestling” by Brent Jones © 2018 Courtesy of https://openclipart.org EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD ANTHONY ADAH FALON DEIMLER Minnesota State University, Moorhead University of Wisconsin-Madison JESSICA AUSTIN HANNAH DODD Anglia Ruskin University The Ohio State University AARON BARLOW ASHLEY M. DONNELLY New York City College of Technology (CUNY) Ball State University Faculty Editor, Academe, the magazine of the AAUP JOSEF BENSON LEIGH H. EDWARDS University of Wisconsin Parkside Florida State University PAUL BOOTH VICTOR EVANS DePaul University Seattle University GARY BURNS JUSTIN GARCIA Northern Illinois University Millersville University KELLI S. BURNS ALEXANDRA GARNER University of South Florida Bowling Green State University ANNE M. CANAVAN MATTHEW HALE Salt Lake Community College Indiana University, Bloomington ERIN MAE CLARK NICOLE HAMMOND Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota University of California, Santa Cruz BRIAN COGAN ART HERBIG Molloy College Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne JARED JOHNSON ANDREW F. HERRMANN Thiel College East Tennessee State University JESSE KAVADLO MATTHEW NICOSIA Maryville University of St. -

Professional Wrestling, Sports Entertainment and the Liminal Experience in American Culture

PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING, SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT AND THE LIMINAL EXPERIENCE IN AMERICAN CULTURE By AARON D, FEIGENBAUM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2000 Copyright 2000 by Aaron D. Feigenbaum ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many people who have helped me along the way, and I would like to express my appreciation to all of them. I would like to begin by thanking the members of my committee - Dr. Heather Gibson, Dr. Amitava Kumar, Dr. Norman Market, and Dr. Anthony Oliver-Smith - for all their help. I especially would like to thank my Chair, Dr. John Moore, for encouraging me to pursue my chosen field of study, guiding me in the right direction, and providing invaluable advice and encouragement. Others at the University of Florida who helped me in a variety of ways include Heather Hall, Jocelyn Shell, Jim Kunetz, and Farshid Safi. I would also like to thank Dr. Winnie Cooke and all my friends from the Teaching Center and Athletic Association for putting up with me the past few years. From the World Wrestling Federation, I would like to thank Vince McMahon, Jr., and Jim Byrne for taking the time to answer my questions and allowing me access to the World Wrestling Federation. A very special thanks goes out to Laura Bryson who provided so much help in many ways. I would like to thank Ed Garea and Paul MacArthur for answering my questions on both the history of professional wrestling and the current sports entertainment product. -

July 2019 Wrestlenado Review “Tell Me a Story” What’S Coming Up

July 2019 Wrestlenado Review “tell me a story” What’s Coming up Issue Number One A Letter from the Editor I suspect it is the same for all of us but my first experience of wrestling was not through live indie show. I saw wrestling on television, and saw wrestlers in the movies and became interested, I sought out wrestling on the internet and on streaming services and became a fan. Seeking out, going to and falling for my local indie promotions was just the latest in a long development of my wrestling watching journey. A natural consequence of that is that I tend to describe what I am learning about with reference to what I already know. It’s an attempt to provide a context, rather than a suggestion of a lack of originality. When I describe Mitch McCarthy as the Kasius Ohno of south east qld, it is to say that he presents as a true fan of the art form, able to work with anyone, and make them look great in doing so.. It’s the natural ability, not just the look that sees me looking at GenNxt and wondering why Pink Matt Riddle has teamed up with Pink Dash Wilder, and there is something almost ‘GoldDustian’ in Adonis’s commitment to the character. I do it when I see visiting performers for the first time too. There is something of Colt Cabana in a Corndog match, by which I mean there is real crowd engagement and knowing humour, in a form that also includes sound fundamentals. -

Wxw Holds Keynote on Wxw NOW Streaming

wXw holds keynote on wXw NOW streaming service, announces details on Germany's first wrestling network wXw just announced the first in-depth details on our new "wXw NOW" streaming network, which will launch one month from now on 8/13 at www.wxwnow.de. It will not just be a collection of shows like a lot of companies offer for a monthly fee via Pivotshare but also offer original content and a lot of archived shows, some dating back as far as 2006. We will also have our uniquely designed interface/UI, while hosting and infrastructure will be managed by Vimeo, our long-time streaming partner, dating back to 2013. Wrestling journalist Markus Gronemann (DarkMat.eu, Wrestling Observer) considers this to be the biggest launch of an over-the-top pro wrestling channel by a single promotion since New Japan World. wXw Managing Director Christian Jakobi held a keynote presentation tonight at 8 pm CEST at the wXw Wrestling Academy training school, which was streamed live on Facebook (the video is available, albeit only in German, here) and talked about what future and past events and what kind of original content would be available. We had up to 750 viewers simultaneously on Facebook and also had some students and a trainer (Toby Blunt) in attendance to provide some crowd noise and cheering at key points during the announcement. Marquee Events are wXw's version of pay-per-view caliber shows, where feuds start and end and international talent often appears. There currently are 10 marquee events on the calendar, with some of them being multi-day shows: -

The Operational Aesthetic in the Performance of Professional Wrestling William P

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling William P. Lipscomb III Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Lipscomb III, William P., "The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3825. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3825 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE OPERATIONAL AESTHETIC IN THE PERFORMANCE OF PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by William P. Lipscomb III B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1990 B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1991 M.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1993 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 William P. Lipscomb III All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am so thankful for the love and support of my entire family, especially my mom and dad. Both my parents were gifted educators, and without their wisdom, guidance, and encouragement none of this would have been possible. Special thanks to my brother John for all the positive vibes, and to Joy who was there for me during some very dark days. -

Make Music With

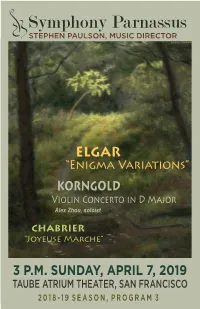

Symphony Parnassus STEPHEN PAULSON, MUSIC DIRECTOR SAPLING HILL by KEVIN BROWN ELGAR “Enigma Variations” KORNGOLD Violin Concerto in D Major Alex Zhou, soloist CHABRIER “Joyeuse Marche” 3 P.M. SUNDAY, APRIL 7, 2019 TAUBE ATRIUM THEATER, SAN FRANCISCO 2018-19 SEASON, PROGRAM 3 About Symphony Parnassus “The best of the Bay Area’s community musicians” —Michael Tilson Thomas Longtime San Francisco residents may remember Symphony Parnassus’s ancestor, the Doctors’ Symphony, which began in 1965 when a few doctors’ chamber groups coalesced for the first time into an orchestra. Lyn Giovanniello, a recent member of our string bass section, was drafted by the Doctors’ Symphony to be their first conductor. The group met regularly and presented concerts at what was then UC Hospital through the 1970s. Almost a decade after that organization folded, biophysics graduate student and amateur cellist Jonathan Davis re-established it as the more community-oriented UCSF Orchestra. He obtained funding from UCSF and started giving concerts in the UCSF Gym in 1989. Davis was able to tap an enthusiastic, supportive pool of both amateur and professional musicians from the faculty, staff and student body of UCSF as well as the local community. The UCSF Orchestra quickly grew, attracted large live jazz audiences, and earned a reputation for outstanding performances. craft cocktails After six years at the orchestra’s helm, Jonathan Davis moved to Boston to pursue his career, and Jeremy Swerling was named music director. Two years food til late later, the orchestra elected Stephen Paulson as its third music director. After being cut from UCSF’s budget in 1999, the orchestra was reorganized as a nonprofit entity with the name Symphony Parnassus, to honor its roots in San Francisco’s Parnassus Heights neighborhood. -

PWTORCH NEWSLETTER • PAGE 2 Www

ISSUE #1255 - MAY 26, 2012 TOP FIVE STORIES OF THE WEEK PPV ROUNDTABLE (1) Raw expanding to three hours on July 23 (2) Impact going live every week this summer (3) Flair parting ways with TNA, WWE bound WWE OVER THE LIMIT (4) Raw going “interactive” with weekly voting Staff Scores & Reviews (5) Laurinaitis pins Cena after Show turns heel Pat McNeill, columnist (6.5): The main problem with WWE Over The Limit? The main event went over the limit of what we’ll accept from WWE. You can argue that there was no reason to book John Cena against John Laurinaitis on a pay-per-view, and you’d be right. RawHEA eDLxINpE AaNnALYdSsIS to thrhoeurse, a nhd uosuaullyr tsher e’Js eunoulgyh re2de3eming But on top of that, there was no reason to book content to make it worth the investment. But Cena versus Laurinaitis to go as long as any other three hours? Three hours of lousy content is By Wade Keller, editor major pay-per-view match. And there was no enough that next time viewers might just tune in reason for Cena to drag the match out. It didn’t fit If you follow an industry long enough, you’re for a just an hour instead of the usual two and the storyline. And it made John Cena look like a bound to see some bad decisions being made. certainly not commit to all three. Or they might chump. or like The Stinger, when Big Show turned Some are worse than others, but it’s rare when pick their segments, watching the predictably heel for the umpteenth time and cost him the you think you might be seeing the Worst newsmaking segments at the start of each hour match. -

University Dodges Isabel

An Associated Collegiate Press Pacemaker Award Winner • THE • Frankfurt 1\Iotor Sho·w Football dominates unveils ne'" concept cars, Rams. ~9-7. Bl Cl 250 University Center University of Delaware Newark. DE 19716 Tuesday & Friday • • FREE yolurn,~ 130, Issue 5 --; ,·. ~ ·. -- , · · www.review.udel.edu · ·· ,._.: ~~ - ::_:~.,~~7:-:-.- ·.· · · ·:!f:;-"·~--!:~'-; · September 23, 2003 University dodges Isabel B\ :\ \T.\LIE BISHOP \'II) K \TIE "cnt tnto effect I hur..,da\ mormn!! and fcrcd signilicant damage. things could fAHE.RT\ c:xtcndcd unttl I nda~ ntght - ha,·c been '' orsc. \tu/1 "' Pubhc. sdwols closed for a four "\Yc ''ere hit hard ,til O\Cr the H urn cane babel ''ashed ashore day \\ cdend ,md restdcnh or IO\\ -I) ing state ... he said. "There was hca\ y flood lhur-.da! aitcrnoon and brought an 6ti areas ''ere C\ acuatt'd The !!O\ crnor mg. dO\\ ned trees and damage tn homes m·ttcd 2.5 tmllion in Jamagcs to the also recommended rcsidcnh tl; sta~ olf all OYer state of Del a\\ arc. the roads. "(HO\\C\Cr]. the qate is holdmg up \s mam a~ 5~.000 rc.,tdt:nts were \lotorish '' ho cho"c to 'cnturt' out prl'll) \\C]I." '' ithout po,~cr because of the storm. had to pi< n routes around the mort' than '\onetheles-,. a signtficant amount and for ~l me. the blackout continued 60 mads that ''ere closed due to llood of cleanup took place thb '' eckcnd in until car' ~undm mg and fallen trees. 0. C\\ ark Go· Rt.;h \nn \1mncr declared a Grt'g Pauerson. -

The Oral Poetics of Professional Wrestling, Or Laying the Smackdown on Homer

Oral Tradition, 29/1 (201X): 127-148 The Oral Poetics of Professional Wrestling, or Laying the Smackdown on Homer William Duffy Since its development in the first half of the twentieth century, Milman Parry and Albert Lord’s theory of “composition in performance” has been central to the study of oral poetry (J. M. Foley 1998:ix-x). This theory and others based on it have been used in the analysis of poetic traditions like those of the West African griots, the Viking skalds, and, most famously, the ancient Greek epics.1 However, scholars have rarely applied Parry-Lord theory to material other than oral poetry, with the notable exceptions of musical forms like jazz, African drumming, and freestyle rap.2 Parry and Lord themselves, on the other hand, referred to the works they catalogued as performances, making it possible to use their ideas beyond poetry and music. The usefulness of Parry-Lord theory in studies of different poetic traditions tempted me to view other genres of performance from this perspective. In this paper I offer up one such genre for analysis —professional wrestling—and show that interpreting the tropes of wrestling through the lens of composition in performance provides information that, in return, can help with analysis of materials more commonly addressed by this theory. Before beginning this effort, it will be useful to identify the qualities that a work must possess to be considered a “composition in performance,” in order to see if professional wrestling qualifies. The first, and probably most important and straightforward, criterion is that, as Lord (1960:13) says, “the moment of composition is the performance.” This disqualifies art forms like theater and ballet, works typically planned in advance and containing words and/or actions that must be performed at precise times and following a precise order. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide