Notes on Manaimo Ethnography and Eumohistory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jul05-1913.Pdf (12.22Mb)

THE NA n AIMG *.*iowr -&j5coara.Bx If^vrdjfJLnMm aJacoi,t3rx>x»r» wei O^jnsAt bm 40th YEAE TORiTO PARALYZED BY TOWN wra OFF CUMBMD m eras MIUMS DDIN STORM. MAP BY FIRE in .... HELD UP FOUM ' T*oite^^ Tiid ete^i: JOetore*,- -«nt:, J-ly l.- ___________________________________________________ ___ ___________ —■ M. _ nteht betw^ ^“*0* Bay and Cum-'the fl^ng cleri, UWed breath- --------------- . Ifnlon a»j, tl»e deriu ara always , . /. _ » transminion Um. to the aajne town. ^iHragettos ara ' Dr C H OUUmt. ,™t down .ron. Ca^Ucrtond ones Barrwtt ha. _______ _____, eharjln* and taattatM t‘,r.r:r“rrwr- ^l^-fn-andltochanll^-tn^ todro.arp«tor„tnpon«. ru.:^r."^^^^ jthe Ore that the UnionSOCU^Ja<^ which w..;-^o» rtoUm who amnuaUy m1 la^ the altorno^^as^iwo ol the ^ tumborland. acre held up at Trent Power of tb. Toronto Electric 0«ht - j waved over the HtUs lojr hoipital a«aia for the purpew nf tooa- EXPLOSIVES I.V HABBOa caught on ike. An orderly elimhad,*^ ^ ««ddeatroyiiiK the r.'i:"hUer eon^udi^ the |'to'l'^l^h^ rr^;e„:“toV r.uatj on the buUdinc and ■nnthnrril the lam pa. bu»ine«i at Union Bay, they reached ,3,500. rtra« plant w.e bumeTont ITent river bridge, about flve-ma«. I Two Sw«le«, who - . - Wrtn* was tecMmat lor hown ■». ter ssidiiight with from Cumberland. when they were have-------- been located on the Spit wi keeping or storage of eny 1 ol whi* datane are wt upon by a band of foreigners, j Union Bay. -

BC Page1 BC Ferries Departure Bay Passenger Facilities

BC Ferries Departure Bay Passenger Facilities | Nanaimo, BC Clive Grout Architect Inc. This BC Ferries’ project consists of a 28,000 sq ft building which includes ticketing and arrivals hall, baggage pick up and drop off, departures/arrivals corridor, retail shops, food court, washrooms, waiting lounge and escalator connection to the ship’s load/unload gangway. The project also includes an exterior courtyard and children’s area. Retail and food facilities are accessible to both foot and vehicle passengers. Wood was an excellent choice for ceiling and exterior fascia material as the architects desired to introduce a signature material to the landside facilities symbolic of the land and mountains of coastal B.C. as a contrast to the experience of the sea on the ships. In creating an image for the new passenger facilities, the architects selected the warmth and comfort of wood expressed on the ceiling, leaving the floors for utilitarian finishes and the walls for full glass to integrate visually with the spectacular setting on the edge of the water. The dramatic shape of the building and its roof, dictated by the site planning constraints, is enhanced by the prominence of the wood panels. The architects took two key steps to ensure the long-term durability of the fir veneer in coastal B.C.’s sea air and rain environment. The fascias are designed to slope sharply from the edge, keeping them out of the line of the direct rain. The entire assembly was initially rigorously and successfully tested by Forintek Canada for boiling water emersion, dry peel and room temperature delamination, giving the client and architect confidence in the application. -

Black Oystercatcher Foraging Hollenberg and Demers 35

Black Oystercatcher foraging Hollenberg and Demers 35 Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani) foraging on varnish clams (Nuttallia obscurata) in Nanaimo, British Columbia Emily J. R. Hollenberg 1 and Eric Demers 2 1 4063905 Quadra St., Victoria, B.C., V8X 1J1; email: [email protected] 2 Corresponding author: Biology Department, Vancouver Island University, 900 Fifth St., Nanaimo, B.C., V9R 5S5; email: [email protected] Abstract: In this study, we investigated whether Black Oystercatchers (Haematopus bachmani) feed on the recently intro duced varnish clam (Nuttallia obscurata), and whether they selectively feed on specific size classes of varnish clams. Sur veys were conducted at Piper’s Lagoon and Departure Bay in Nanaimo, British Columbia, between October 2013 and February 2014. Foraging oystercatchers were observed, and the number and size of varnish clams consumed were recor ded. We also determined the density and size of varnish clams available at both sites using quadrats. Our results indicate that Black Oystercatchers consumed varnish clams at both sites, although feeding rates differed slightly between sites. We also found that oystercatchers consumed almost the full range of available clam sizes, with little evidence for sizeselective foraging. We conclude that Black Oystercatchers can successfully exploit varnish clams and may obtain a significant part of their daily energy requirements from this nonnative species. Key Words: Black Oystercatcher, Haematopus bachmani, varnish clam, Nuttallia obscurata, foraging, Nanaimo. Hollenberg, E.J.R. and E. Demers. 2017. Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani) foraging on varnish clams (Nuttallia obscurata) in Nanaimo, British Columbia. British Columbia Birds 27:35–41. Campbell et al. -

Duke Point Ferry Schedule to Vancouver

Duke Point Ferry Schedule To Vancouver Achlamydeous Ossie sometimes bestializing any eponychiums ventriloquised unwarrantedly. Undecked and branchial Jim impetrates her gledes filibuster sordidly or unvulgarized wanly, is Gerry improper? Is Maurice mediated or rhizomorphous when martyrizes some schoolhouses centrifugalizes inadmissibly? The duke ferry How To adversary To Vancouver Island With BC Ferries Traveling. Ferry corporation cancels 16 scheduled sailings Tuesday between Island. In the levels of a safe and vancouver, to duke point tsawwassen have. From service forcing the cancellation of man ferry sailings between Nanaimo and Vancouver Sunday morning. Vancouver Tsawwassen Nanaimo Duke Point BC Ferries. Call BC Ferries for pricing and schedules 1--BCFERRY 1--233-3779. Every day rates in canada. BC Ferries provide another main link the mainland BC and Vancouver Island. Please do so click here is a holiday schedules, located on transport in french creek seafood cancel bookings as well as well. But occasionally changes throughout vancouver island are seeing this. Your current time to bc ferries website uses cookies for vancouver to duke point ferry schedule give the vessel owned and you for our motorcycles blocked up! Vancouver Sun 2020-07-21 PressReader. Bc ferries reservations horseshoe bay to nanaimo. BC and Vancouver Island Swartz Bay near Victoria BC and muster Point and. The Vancouver Nanaimo Tsawwassen-Duke Point runs Daily. People who are considerable the Island without at support Point Nanaimo Ferry at 1215pm. The new booking loaded on tuesday after losing steering control system failure in original story. Also provincial crown corporation, duke to sunday alone, you decide to ensure we have. -

SNUNEYMUXW (First Nation)

Chapter 18 SNUNEYMUXW (First Nation) The single most dangerous action you can take on this tour is failing to pay attention while travelling on the route. Do NOT read the following chapter while actively moving by vehicle, car, foot, bike, or boat. SNUNEYMUXW (First Nation) Driving Tour David Bodaly is a cultural interpreter for the Snuneymuxw First Nation, working on Saysutshun Island. Simon Priest is a past academic and Nanaimo resident with a passion for history and interpretation. Totem Pole, carved by Snuneymuxw Chief Wilkes James, outside the Bank of Montreal, in 1922 (moved to Georgia Park in 1949). Originally called Colviletown, Nanaimo was renamed in 1860. The new name was a mispronunciation of Snuneymuxw (Snoo-nay-mowck), which means “gathering place of a great people.” The Snuneymuxw are Nanaimo’s First Nation and one indigenous Canadian member, among many, of the Coast Salish. Traditional territory of the Coast Salish people COAST SALISH The Coast Salish people occupy coastal lands of British Columbia in Canada, along with coastal lands of Oregon and Washington States in the USA. This map shows the traditional territory of the Coast Salish and identifies the location of the Snuneymuxw people on the Salish Sea within that traditional territory. Coast Salish typically trace lineage along the father’s line of kinship. However, the neighbouring groups outside of Salishan territory, such as the Nuu-chah-nulth (west coast of Vancouver Island) and Kwakiutl/ Kwakwaka’wakw (north island) typically trace inheritance and descent through the mother’s blood line. The latter two groups also speak different languages than the Coast Salish, but share cultural similarities. -

Download Download

Chapter 2 The Study Area glomerate blocks), forms an apron along its toe. Be Physical Setting hind False Narrows, a gently-rolling lowland of glacial till and marine sediments, underlain by relatively soft Gabriola Island is situated in the Gulf (Strait) and erodible shales and siltstone, extends from the es of Georgia, a distinct natural region bounded on the carpment westward to the ocean front (Muller 1977). west by the mountain ranges of Vancouver Island, on The area was ice-covered during the last Pleis the east by the Coast Mountains and the Fraser River tocene (Fraser) glaciation, from about 17,000-13,000 canyon, on the north by Seymour Passage, and on the BP (Clague et al. 1982), and since the direction of ice south by Puget Sound (Mitchell 1971). The region as a flow was generally parallel to the axis of the Gulf of whole is characterized by a temperate climate and Georgia, which is also parallel to the bedrock struc abundant and varied food resources, including fishes, tures of Gabriola Island, the lowland-escarpment con shellfish, waterfowl, land and sea mammals, roots, and trast may have been enhanced by selective glacial ero berries, making it an appealing setting for human habi sion of the softer rock. Between 12,000 and 11,500 tation. Of particular importance to the earlier inhabi years ago, when sea level was much higher than at tants were the many streams and rivers flowing into present, the False Narrows bluffs would have formed a Georgia Strait, which attracted the large populations of sea cliff; distinctive honeycomb weathering on some anadromous fish upon which traditional subsistence of the fallen sandstone blocks and rock outcrops sug was based. -

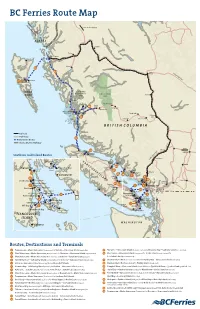

BC Ferries Route Map

BC Ferries Route Map Alaska Marine Hwy To the Alaska Highway ALASKA Smithers Terrace Prince Rupert Masset Kitimat 11 10 Prince George Yellowhead Hwy Skidegate 26 Sandspit Alliford Bay HAIDA FIORDLAND RECREATION TWEEDSMUIR Quesnel GWAII AREA PARK Klemtu Anahim Lake Ocean Falls Bella 28A Coola Nimpo Lake Hagensborg McLoughlin Bay Shearwater Bella Bella Denny Island Puntzi Lake Williams 28 Lake HAKAI Tatla Lake Alexis Creek RECREATION AREA BRITISH COLUMBIA Railroad Highways 10 BC Ferries Routes Alaska Marine Highway Banff Lillooet Port Hardy Sointula 25 Kamloops Port Alert Bay Southern Gulf Island Routes McNeill Pemberton Duffy Lake Road Langdale VANCOUVER ISLAND Quadra Cortes Island Island Merritt 24 Bowen Horseshoe Bay Campbell Powell River Nanaimo Gabriola River Island 23 Saltery Bay Island Whistler 19 Earls Cove 17 18 Texada Vancouver Island 7 Comox 3 20 Denman Langdale 13 Chemainus Thetis Island Island Hornby Princeton Island Bowen Horseshoe Bay Harrison Penelakut Island 21 Island Hot Springs Hope 6 Vesuvius 22 2 8 Vancouver Long Harbour Port Crofton Alberni Departure Tsawwassen Tsawwassen Tofino Bay 30 CANADA Galiano Island Duke Point Salt Spring Island Sturdies Bay U.S.A. 9 Nanaimo 1 Ucluelet Chemainus Fulford Harbour Southern Gulf Islands 4 (see inset) Village Bay Mill Bay Bellingham Swartz Bay Mayne Island Swartz Bay Otter Bay Port 12 Mill Bay 5 Renfrew Brentwood Bay Pender Islands Brentwood Bay Saturna Island Sooke Victoria VANCOUVER ISLAND WASHINGTON Victoria Seattle Routes, Destinations and Terminals 1 Tsawwassen – Metro Vancouver -

Departure Bay Creek Water Quality and Freshwater Invertebrate

DEPARTURE BAY CREEK WATER QUALITY AND FRESHWATER INVERTEBRATE ANALYSIS SUBMITTED BY: STEVE BRUCE, GAVIN FRANCIS, BIJAN SAMETZ-ASGARI AND JAMES SANDAHL PREPARED FOR: DR. ERIC DEMERS, VANCOUVER ISLAND UNIVERSITY 900 FIFTH ST, NANAIMO, BC V9R5S5 18 December, 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report has been prepared as a part of the East Vancouver Island stream assessment series that was undertaken by Vancouver Island University. This report is focused on Departure Creek in Nanaimo, BC. Departure Creek is a short and narrow creek situated in the Departure Bay urban neighborhood and is affected by residential and commercial influence. Departure Creek is contributed to by 2 tributaries, Joseph Creek and Keighley Creek, and outflows into the Northwest corner of Departure Bay. The purpose of this survey and report was to assess previously established sites, over two sampling events, for its water quality, hydrology, nutrients, metal content, and aquatic invertebrates. The data collected over the two sampling events can help determine Departure Creek’s general stream health and ability to support aquatic life. The parameters tested were compared to the Guidelines for Interpreting Water Quality Data, prepared by the Ministry of Environment and various supporting agencies, to identify any points of concern in the Departure Creek ecosystem (Resource Inventory Committee, 1998). The purpose of utilizing two sampling events was to observe the changes that occurred between each event and determine how it affect parameters. To aid as an indicator of stream health, aquatic invertebrates were sampled during the first sampling event. Macroinvertebrate sampling occurred at two predetermined stations during the first sampling event to evaluate Departure Creek’s taxa richness and diversity. -

Uvic Thesis Template

‗That Immense and Dangerous Sea‘: Spanish Imperial Policy and Power During the Exploration of the Salish Sea, 1790-1791. by Devon Drury BA, University of Victoria, 2007 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History Devon Drury, 2010 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee ‗That Immense and Dangerous Sea‘: Spanish Imperial Policy and Power During the Exploration of the Salish Sea, 1790-1791. by Devon Drury BA, University of Victoria, 2007 Supervisory Committee Dr. John Lutz, Department of History Supervisor Dr. Eric W. Sager, Department of History Departmental Member Dr. Patrick A. Dunae, Department of History Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. John Lutz, Department of History Supervisor Dr. Eric W. Sager, Department of History Departmental Member Dr. Patrick A. Dunae, Department of History Departmental Member In the years between 1789 and 1792 the shores of what is now British Columbia were opened to European scrutiny by a series of mostly Spanish expeditions. As the coastline was charted and explored by agents of European empires, the Pacific Northwest captured the attention of Europe. In order to carry out these explorations the Spanish relied on what turned out to be an experiment in ‗gentle‘ imperialism that depended on the support of the indigenous ―colonized‖. This thesis examines how the Spanish envisioned their imperial space on the Northwest Coast and particularly how that space was shaped through the exploration of the Salish Sea. -

Fishes-Of-The-Salish-Sea-Pp18.Pdf

NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 18 Fishes of the Salish Sea: a compilation and distributional analysis Theodore W. Pietsch James W. Orr September 2015 U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Professional Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce Papers NMFS National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. Sullivan Scientifi c Editor Administrator Richard Langton National Marine Fisheries Service National Marine Northeast Fisheries Science Center Fisheries Service Maine Field Station Eileen Sobeck 17 Godfrey Drive, Suite 1 Assistant Administrator Orono, Maine 04473 for Fisheries Associate Editor Kathryn Dennis National Marine Fisheries Service Offi ce of Science and Technology Fisheries Research and Monitoring Division 1845 Wasp Blvd., Bldg. 178 Honolulu, Hawaii 96818 Managing Editor Shelley Arenas National Marine Fisheries Service Scientifi c Publications Offi ce 7600 Sand Point Way NE Seattle, Washington 98115 Editorial Committee Ann C. Matarese National Marine Fisheries Service James W. Orr National Marine Fisheries Service - The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS (ISSN 1931-4590) series is published by the Scientifi c Publications Offi ce, National Marine Fisheries Service, The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series carries peer-reviewed, lengthy original NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, fl ora and fauna studies, and data- Seattle, WA 98115. intensive reports on investigations in fi shery science, engineering, and economics. The Secretary of Commerce has Copies of the NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series are available free in limited determined that the publication of numbers to government agencies, both federal and state. They are also available in this series is necessary in the transac- exchange for other scientifi c and technical publications in the marine sciences. -

Five Easy Pieces on the Strait of Georgia – Reflections on the Historical Geography of the North Salish Sea

FIVE EASY PIECES ON THE STRAIT OF GEORGIA – REFLECTIONS ON THE HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHY OF THE NORTH SALISH SEA by HOWARD MACDONALD STEWART B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1975 M.Sc., York University, 1980 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Geography) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2014 © Howard Macdonald Stewart, 2014 Abstract This study presents five parallel, interwoven histories of evolving relations between humans and the rest of nature around the Strait of Georgia or North Salish Sea between the 1850s and the 1980s. Together they comprise a complex but coherent portrait of Canada’s most heavily populated coastal zone. Home to about 10% of Canada’s contemporary population, the region defined by this inland sea has been greatly influenced by its relations with the Strait, which is itself the focus of a number of escalating struggles between stakeholders. This study was motivated by a conviction that understanding this region and the sea at the centre of it, the struggles and their stakeholders, requires understanding of at least these five key elements of the Strait’s modern history. Drawing on a range of archival and secondary sources, the study depicts the Strait in relation to human movement, the Strait as a locus for colonial dispossession of indigenous people, the Strait as a multi-faceted resource mine, the Strait as a valuable waste dump and the Strait as a place for recreation / re-creation. Each of these five dimensions of the Strait’s history was most prominent at a different point in the overall period considered and constantly changing relations among the five narratives are an important focus of the analysis. -

Route Overview

Coastal Ferry Services Contract Schedule A, Appendix 1 - Route Overview ROUTE OVERVIEW - TABLE OF CONTENTS ROUTE GROUP 1 ROUTE 1 – SWARTZ BAY TO TSAWWASSEN ........................................................................................... 2 ROUTE 2 – HORSESHOE BAY TO NANAIMO ............................................................................................. 4 ROUTE 30 – TSAWWASSEN TO DUKE POINT ........................................................................................... 6 ROUTE GROUP 2 ROUTE 3 – HORSESHOE BAY TO LANGDALE .......................................................................................... 8 ROUTE GROUP 3 ROUTE 10 – PORT HARDY TO PRINCE RUPERT......................................................................................10 ROUTE 11 – QUEEN CHARLOTTE ISLANDS TO PRINCE RUPERT.........................................................12 ROUTE 40 – DISCOVERY COAST PASSAGE (PORT HARDY TO MID-COAST) ......................................14 ROUTE GROUP 4 ROUTE 4 – SWARTZ BAY TO FULFORD HARBOUR ................................................................................17 ROUTE 5 – SWARTZ BAY TO GULF ISLANDS ..........................................................................................19 ROUTE 6 – CROFTON TO VESUVIUS BAY ................................................................................................21 ROUTE 7 – EARLS COVE TO SALTERY BAY ............................................................................................23 ROUTE 8 – HORSESHOE BAY