Gerry Roche "A Memoir"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warriors : Life and Death Among the Somalis Ebook

WARRIORS : LIFE AND DEATH AMONG THE SOMALIS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gerald Hanley | 200 pages | 10 May 2005 | Eland Publishing Ltd | 9780907871835 | English | London, United Kingdom Warriors : Life and Death Among the Somalis PDF Book Whenever it is worth our while to occupy Jubaland, and let them see a few hundred white men instead of half-a-dozen officials, which is literally all that they know of us at present, I anticipate that we shall not have much difficulty in getting on with them. All in all a good read. Like this: Like Loading But the book picks From the point of view of a British Officer during the colonial periods in What was then called Italian Somaliland, this is a book that attempts to describe the immensely complicated people that are the Somalis. Published by Eland Publishing Ltd -. There are a number of competing ideologies as events test the systems and beliefs of the characters. Monsoon Victory This book is an account of the Burma campaign, where Gerald served, from the point of view of a war correspondent attacked to the East African Division. Even so if high quality of your document will not be everything good, don't worry, you'll be able to ask website workers to convert, proof examine or edit in your case having a click of the button. Latest posts. Perhaps this is a real strength in the Somali. If youknow Warriors: Life and death among the Somalis for satisfaction and find yourself battling, make an effort preparing regular reading objectives on your own. Section 1. -

Carroll, Mella

TEXT OF THE INTRODUCTORY ADDRESS delivered by DR HUGH BRADY Pro-Vice-Chancellor of the University, President of University College Dublin – NUI, Dublin, on 21 April 2004 on the occasion of the Conferring of the Degree of Doctor of Laws honoris causa upon MELLA CARROLL A Sheansailéir, agus a mhuintir na hOllscoile: The Honorable Ms. Justice Mella Carroll was born in Dublin in 1934. She came to University College Dublin in the 1950’s and graduated with a BA in French and German. She subsequently went on to study Law at King’s Inns and was called to the Irish Bar in 1957. In 1976 she was called to the Bar in Northern Ireland and, a year later, became a Senior Counsel and a member of the Inner Bar. For a period she was the only female Senior Counsel practising in the Irish State. In 1979 she was elected Chairperson of the Bar Council. Then in 1980 Mella Carroll received the signal honour of being appointed the first woman judge of the High Court. She is now the longest serving member of that Court and during the intervening years has discharged the duties and responsibilities of her judicial office with great distinction, unfailing courtesy, and enormous integrity. Her formidable forensic talents were put to excellent use in another judicial context. For fifteen years she served on the Administrative Tribunal of the International Labour Organisation which is based in Geneva and, for a time, was appointed Vice-President of that Tribunal. The esteem in which Ms Justice Carroll is held by her fellow jurists was further evidenced by her appointment as President of the International Association of Women Judges. -

Rebellion, Resistance and the Irish Working Class

Rebellion, Resistance and the Irish Working Class Rebellion, Resistance and the Irish Working Class: The Case of the ‘Limerick Soviet’ By Nicola Queally Rebellion, Resistance and the Irish Working Class: The Case of the ‘Limerick Soviet’, by Nicola Queally This book first published 2010 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2010 by Nicola Queally All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-2058-X, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-2058-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One................................................................................................. 7 Ireland 1916-1919 Chapter Two.............................................................................................. 19 The Strike Chapter Three............................................................................................ 29 The Role of Political Parties Chapter Four.............................................................................................. 37 Strikes in Russia, Germany and Scotland Conclusion................................................................................................ -

Gazette€3.75 March 2006

LAW SOCIETY Gazette€3.75 March 2006 PULLINGPULLING TOGETHERTOGETHER Collaborative family law TIPPERARYTIPPERARY STARSTAR John Carrigan interviewed DODO YOUYOU UNDERSTAND?UNDERSTAND? The Interpretation Act 2005 STRANGE FRUIT: Schools bite the rotten apple of classroom litigation INSIDE: VICTIM IMPACT STATEMENTS • PRACTICE DOCTOR • MEMBER SERVICES SURVEY • YOUR LETTERS LAW SOCIETY GAZETTE CONTENTS On the cover LAW SOCIETY Schools are on the alert, given certain recent judgments in bullying actions, which state that the standard of care Gazette required from them is that of a ‘prudent parent’ March 2006 Volume 100, number 2 Subscriptions: €57.15 REGULARS 5 News Solicitors under pressure 6 The report of the Support Services Task Force has found that the pressures on solicitors caused by ‘too heavy a workload’ is the greatest barrier to successful practice ‘Unprecedented’ costs order 7 The President of the High Court, Mr Justice Finnegan, has granted an application by the Law Society to be joined as an amicus curiae in an appeal against a ‘wasted costs’ order of the Master of the High Court 5 Viewpoint 14 Victim impact statements were initially introduced for very good reasons. A review of how the system works is overdue, argues Dara Robinson 17 Letters 41 People and places 43 Book reviews Briefing 47 47 Council report 48 Practice notes 49 Practice directions 14 50 Legislation update: acts passed in 2005 52 FirstLaw update 57 Eurlegal: EC competition law 59 Professional notices Recruitment advertising 64 Ten pages of job vacancies Editor: Mark McDermott. Deputy editor: Garrett O’Boyle. Designer: Nuala Redmond. Editorial secretaries: Catherine Kearney, Valerie Farrell. -

English for Specific Purposes 1 Esercitazioni (James)

DISPENSA A.A. 2018 – 2019 English for Specific Purposes 1 Esercitazioni (James) Risk Recreation Ethical Tourism Cultural Heritage (051-2097241; [email protected]) 1 Contents Page 1 Writing 3 Guidelines on essay assessment, writing, style, organization and structure 2 Essay writing exercises 13 3 Reading texts (including reading, listening and writing exercises) Risk Recreation: Tornado Tourism (essay assignment) 20 Ethical tourism: Canned Hunting 28 Pamplona Bull Running 36 La Tomatina 43 Museums and the Ownership of Cultural Heritage: The Rosetta Stone, The Parthenon Marbles, The Mona Lisa 45 (essay assignment) The Impact of Mass Tourism: Venice, Florence, Barcelona 68 All the copyrighted materials included in this ‘dispensa’ belong to the respective owners and, following fair use guidelines, are hereby used for educational purposes only. 2 1 Writing Guidelines on essay assessment, writing, style, organization and structure Assessing writing: criteria Exam task: 500-word argument essay 1 Task achievement (9 points) Has the student focused on the question and respected the length? Fully answers the question in depth. Answers the question in sufficient depth to cover the main points. There are some unnecessary or irrelevant ideas. There are too many minor issues or irrelevant ideas dealt with. Shorter than the required length. Does not answer the question. Much shorter than the required length. 2 Structure and organization (9 points) Does the essay have a structure? Is there an introduction and conclusion? Is the body divided into paragraphs which are linked? There is a suitable introduction and conclusion. Paragraphs and sentences link up and make the essay easy to read and the text easy to understand. -

Ireland and the Russian Revolution

Ireland and the Russian Revolution Colm Bryce22 In February 1918, an estimated 10,000 ‘workers’ parliament’. That is people packed into the Mansion House in the language of the Bolshevists Dublin to ‘hail with delight the advent of and Sinn Féiners and it should the Russian Bolshevik revolution’.1 The open the eyes of the authorities, speakers included some of the most promi- and also of the vast majority of nent figures in the Irish revolutionary move- the men, who are loyal and law ment such as Maud Gonne and Constance abiding, to the real objectives of Markievicz, Tom Johnston of the Labour the strike committee. These ob- Party, a representative of the Soviet gov- jectives are not industrial, but ernment and the meeting was chaired by revolutionary, and if they were William O’Brien, one of the leaders of the attained they would bring disas- 1913 Dublin Lockout. The Red Flag was ter to the city.2 sung and thousands marched through the streets of Dublin afterwards. On May Day 1920, a few months after A few weeks later The Irish Times the general strike, 100,000 workers marched warned against the danger of Bolshevism: in Belfast, under red flags. On the same day, tens of thousands marched in towns and vil- They have invaded Ireland, and lages across the whole of Ireland. The Irish if the democracies do not keep Transport and General Workers Union (IT- their heads, they may extend to GWU) which had called for the marches, de- other countries in Europe. The clared itself in favour of the ‘soviet system’.3 infection of Ireland by the an- In 1918, the British Prime Minister archy of Bolshevism is one of Lloyd George wrote to his counterpart those phenomena which, though Clemenceau in France: almost incredible to reason and experience, are made intelligible The whole of Europe is filled by the accidents of fortune or hu- with the spirit of revolution. -

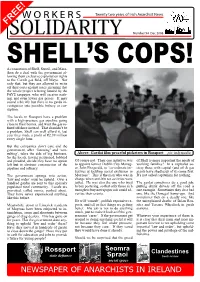

PDF File of WS 94

W O R K E R S Twenty two years of Irish Anarchist News FREE! SOLIDARITY Number 94 Dec 2006 SHELLA consortium of Shell, Statoil, and Mara- ’S COPS! thon do a deal with the government al- lowing them exclusive exploitation rights to the Corrib gas field, off Mayo. Not only that, but they are allowed to write off their costs against taxes, meaning that the whole project is being funded by the PAYE taxpayer, who will receive noth- ing, not even lower gas prices. It may sound a bit iffy but there is no garda in- vestigation into possible bribery or cor- ruption. The locals in Rossport have a problem with a high-pressure gas pipeline going close to their homes, and want the gas re- fined offshore instead. That shouldn’t be a problem, Shell can well afford it, last year they made a profit of !2.39 million every single hour. But the companies don’t care and the government, after ‘listening’ and ‘con- sulting’, takes the side of big business. Above: Gardai film peaceful picketers in Rossport pic:indymedia So the locals, having petitioned, lobbied and pleaded, decide they have no option Of course not. Their one initiative was of Shell is more important the needs of left but to obstruct construction of the to appoint former Dublin City Manag- working families? In a capitalist so- pipeline and refinery. er, John Fitzgerald, to “co-ordinate ini- ciety those with capital (and oil & gas tiatives at tackling social exclusion in giants have shedloads of it) come first. -

Download Date 04/10/2021 06:40:30

Mamluk cavalry practices: Evolution and influence Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Nettles, Isolde Betty Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 06:40:30 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289748 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this roproduction is dependent upon the quaiity of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that tfie author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g.. maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal secttons with small overlaps. Photograpiis included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrattons appearing in this copy for an additk)nal charge. -

Cosmopolitan Trends in the Arts of Ptolemaic Alexandria Autor(Es

Cosmopolitan Trends in the Arts of Ptolemaic Alexandria Autor(es): Haggag, Mona Edições Afrontamento; CITCEM - Centro de Investigação Transdisciplinar «Cultura, Espaço e Memória»; Centro de Estudos Publicado por: Clássicos e Humanísticos; Alexandria University; Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/36161 DOI: DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.14195/978-989-26-0966-9_6 Accessed : 7-Oct-2021 11:08:44 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. pombalina.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt Alexandria endures in our imagination as the first model of cultural interaction – of cosmopolitanism, to use both classical and contemporary terminology – and as the cultural and intellectual capital of the ancient world. -

Egypt: the Royal Tour | October 24 – November 6, 2021 Optional Pre-Trip Extensions: Alexandria, October 21 – 24 Optional Post-Trip Extension: Petra, November 6 - 10

HOUSTON MUSEUM OF NATURAL SCIENCE Egypt: The Royal Tour | October 24 – November 6, 2021 Optional Pre-Trip Extensions: Alexandria, October 21 – 24 Optional Post-Trip Extension: Petra, November 6 - 10 Join the Houston Museum of Natural Science on a journey of a lifetime to tour the magical sites of ancient Egypt. Our Royal Tour includes the must-see monuments, temples and tombs necessary for a quintessential trip to Egypt, plus locations with restricted access. We will begin in Aswan near the infamous cataracts of the River Nile. After visiting Elephantine Island and the Isle of Philae, we will experience Nubian history and culture and the colossal temples of Ramses II and Queen Nefertari at Abu Simbel. Our three-night Nile cruise will stop at the intriguing sites of Kom Ombo, Edfu and Esna on the way to Luxor. We will spend a few days in Egypt 2021: The Royal Tour Luxor to enjoy the Temples of $8,880 HMNS Members Early Bird Luxor and Karnak, the Valley of $9,130 HMNS Members per person the Kings, Queens and Nobles $9,300 non-members per person and the massive Temple of $1,090 single supplement Hatshepsut. Optional Alexandria Extension In Cairo we will enjoy the $1,350 per person double occupancy historic markets and neighborhoods of the vibrant modern city. $550 single supplement Outside of Cairo we will visit the Red Pyramid and Bent Pyramid in Dahshur Optional Petra Extension and the Step Pyramid in Saqqara, the oldest stone-built complex in the $2,630 per person double occupancy world. Our hotel has spectacular views of the Giza plateau where we will $850 single supplement receive the royal treatment of special admittance to stand in front of the Registration Requirements (p. -

Nursing and Midwifery in Ireland in the Twentieth Century: Fifty Years of an Bord Altranais (The Nursing Board) 1950-2000 / by Joseph Robins, Author and Editor

Nursing and midwifery in Ireland in the twentieth century: fifty years of an Bord Altranais (the Nursing Board) 1950-2000 / by Joseph Robins, author and editor Item Type Report Authors An Bord Altranais (ABA) Rights An Bord Altranais Download date 02/10/2021 02:24:04 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10147/46356 Find this and similar works at - http://www.lenus.ie/hse Nursing and Midwifery in Ireland in the Twentieth Century Nursing and Midwifery in Ireland in the Twentieth Century Fifty Years of An Bord Altranais (The Nursing Board) 1950 - 2000 JOSEPH ROBINS Author and Editor 3 First Published in 2000 By An Bord Altranais, Dublin, Ireland © 2000 with An Bord Altranais and the authors for their individual chapters All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 0-953976-0-4 Cover design and typesetting by Total Graphics, Dublin Copy-editing by Jonathan Williams Printed by Colm O’Sullivan & Son (Printing) Limited, Dublin 4 Message from President McAleese have great pleasure in sending my warmest congratulations and good wishes on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the establishment of An IBord Altranais. At this important milestone of the organisation’s establishment it is appropriate to reflect on the developments which have taken place in a profession which is rightly held in such high esteem in this country. Any young woman or man who decides on a career in nursing enters an exciting, demanding world of life long learning. -

Telegraph Travel

TRAVEL BOOKS ‘Freedom is only the insistence of a soul to be left in peace to enjoy the sunrise’ Julian Sayarer’s latest book sees revelations and revolutions in Israel and Palestine, says Michael Kerr t the 2017 Edinburgh Festival, Julian Sayarer told an Israeli writer that travelling by bike allowed you to cut through to something deeper in places, to tell A the truth about them. In that case, she said, he should go to Israel and Palestine. The result is Fifty Miles Wide, in which he weaves from the ancient hills of Galilee, along the walled-in Gaza Strip and down to the Bedouin villages of the Naqab desert. He talks to Palestinian cyclists and hip-hop artists; to Israeli soldiers training for war and to a lawyer who took a leading role in peace talks. His book took courage on the road and is adventurous on the page. It conveys powerfully what life is like for people on both sides of “the world’s most entrenched impasse”. At the same time, it’s full of free spirits and the joys of freewheeling. In the extract below, Sayarer heads for the first time into the hills of Palestine. ‘SENTENCES FORM AS THE WHEELS TURN...’ Julian Sayarer finds philosophy NEWS FROM THE WORLD OF TRAVEL WRITING in the hills of Palestine GETTY IMAGES; ALAMY IMAGES; GETTY Jini Reddy, a London The £10,000 Where does journalist with Ondaatje Prize of Suffolk he goats watch me packed into a sand-coloured jeep, shouts “hello!” and each old man calls multicultural roots, has the Royal heathland meet watching them.