Rebellion, Resistance and the Irish Working Class

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limerick Timetables

Limerick B A For more information For online information please visit: locallinklimerick.ie Call us at: 069 78040 Email us at: [email protected] Ask your driver or other staff member for assistance Operated By: Local Link Limerick Fares: Adult Return/Single: €5.00/€3.00 Student & Child Return/Single: €3.00/€2.00 Adult Train Connector: €1.50 Student/Child Train Connector: €1.00 Multi Trip Adult/Child: €8.00/€5.00 Weekly Student/Child: €12.00 5 day Weekly Adult: €20.00 6 day Weekly Adult: €25.00 Free Travel Pass holders and children under 5 years travel free Our vehicles are wheelchair accessible Contents Route Page Ballyorgan – Ardpatrick – Kilmallock – Charleville – Doneraile 4 Newcastle West Service (via Glin & Shanagolden) 12 Charleville Child & Family Education Centre 20 Spa Road Kilfinane to Mitchelstown 21 Mountcollins to Newcastle West (via Dromtrasna) 23 Athea Shanagolden to Newcastle West Desmond complex 24 Castlemahon via Ballingarry to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 25 Castlmahon to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 26 Ballykenny to Newcastle West- Desmond Complex 27 Shanagolden to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 28 Tournafulla to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 29 Abbeyfeale to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 30 Elton to Hospital 31 Adare to Newcastle West 32 Kilfinny via Adare to Newcastle West 33 Feenagh via Ballingarry to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 34 Knockane via Patrickswell to Dooradoyle 35 Knocklong to Dooradoyle 36 Rathkeale via Askeaton to Newcastle West to Desmond Complex 37 Ballingarry to -

Ireland and the Russian Revolution

Ireland and the Russian Revolution Colm Bryce22 In February 1918, an estimated 10,000 ‘workers’ parliament’. That is people packed into the Mansion House in the language of the Bolshevists Dublin to ‘hail with delight the advent of and Sinn Féiners and it should the Russian Bolshevik revolution’.1 The open the eyes of the authorities, speakers included some of the most promi- and also of the vast majority of nent figures in the Irish revolutionary move- the men, who are loyal and law ment such as Maud Gonne and Constance abiding, to the real objectives of Markievicz, Tom Johnston of the Labour the strike committee. These ob- Party, a representative of the Soviet gov- jectives are not industrial, but ernment and the meeting was chaired by revolutionary, and if they were William O’Brien, one of the leaders of the attained they would bring disas- 1913 Dublin Lockout. The Red Flag was ter to the city.2 sung and thousands marched through the streets of Dublin afterwards. On May Day 1920, a few months after A few weeks later The Irish Times the general strike, 100,000 workers marched warned against the danger of Bolshevism: in Belfast, under red flags. On the same day, tens of thousands marched in towns and vil- They have invaded Ireland, and lages across the whole of Ireland. The Irish if the democracies do not keep Transport and General Workers Union (IT- their heads, they may extend to GWU) which had called for the marches, de- other countries in Europe. The clared itself in favour of the ‘soviet system’.3 infection of Ireland by the an- In 1918, the British Prime Minister archy of Bolshevism is one of Lloyd George wrote to his counterpart those phenomena which, though Clemenceau in France: almost incredible to reason and experience, are made intelligible The whole of Europe is filled by the accidents of fortune or hu- with the spirit of revolution. -

PDF File of WS 94

W O R K E R S Twenty two years of Irish Anarchist News FREE! SOLIDARITY Number 94 Dec 2006 SHELLA consortium of Shell, Statoil, and Mara- ’S COPS! thon do a deal with the government al- lowing them exclusive exploitation rights to the Corrib gas field, off Mayo. Not only that, but they are allowed to write off their costs against taxes, meaning that the whole project is being funded by the PAYE taxpayer, who will receive noth- ing, not even lower gas prices. It may sound a bit iffy but there is no garda in- vestigation into possible bribery or cor- ruption. The locals in Rossport have a problem with a high-pressure gas pipeline going close to their homes, and want the gas re- fined offshore instead. That shouldn’t be a problem, Shell can well afford it, last year they made a profit of !2.39 million every single hour. But the companies don’t care and the government, after ‘listening’ and ‘con- sulting’, takes the side of big business. Above: Gardai film peaceful picketers in Rossport pic:indymedia So the locals, having petitioned, lobbied and pleaded, decide they have no option Of course not. Their one initiative was of Shell is more important the needs of left but to obstruct construction of the to appoint former Dublin City Manag- working families? In a capitalist so- pipeline and refinery. er, John Fitzgerald, to “co-ordinate ini- ciety those with capital (and oil & gas tiatives at tackling social exclusion in giants have shedloads of it) come first. -

Gerry Roche "A Memoir"

A Survivor’s Story: a memoir of a life lived in the shadow of a youthful brush with psychiatry by Gerry Roche And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time. TS Eliot: Four Quartets Contents Introduction 4 Chapter 1 : Ground Zero 7 1971: Lecturing, Depression, Drinking, John of Gods, … Chapter 2 : Zero minus one 21 1945-71: Childhood, School, University … Chapter 3 : Zero’s aftermath: destination ‘cold turkey’ 41 1971-81: MSc., Lecturing, Sculpting, Medication-free, Building Restoration, …… Chapter 4 : After ‘cold turkey’: the cake 68 1981-92: Tibet, India, Log Cabin Building, … Chapter 5 : And then the icing on the cake 105 1992-96: China, Karakoram, more Building, Ethiopia, ... Chapter 6 : And then the cognac … (and the bitter 150 lemon) 1996-2012: MPhil, Iran, Japan, PhD, more Building, Syria ... (and prostate cancer) … Chapter 7 : A Coda 201 2012-15: award of PhD … Armenia, Korea, … Postscript : Stigma: an inerasable, unexpungeable, 215 indestructible, indelible stain. Appendix: : Medical interventions on the grounds of 226 ‘best interests’ Endnotes 233 2 I wish to dedicate this memoir to my sons Philip and Peter and to their mother (and my-ex-wife) Mette, with love and thanks. I wish to give a special word of thanks to Ms. Maureen Cronin, Mr. Brian McDonnell, Mr. Charles O’Brien and Ms. Jill Breivik who assisted me in editing this memoir. 3 Introduction A cure is not overcoming anything, a cure is learning to live with what your are, and with what the past has made you, with what you've made of yourself with your own past .1 The story that I tell is of a journey, or perhaps more of an enforced wandering or a detour occasioned by what, at the time, seemed as inconsequential as the taking of a short break. -

LIMERICK Service Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Town County Registered Provider Telephone Number Service Type Conditions of Service Attached

Early Years Services LIMERICK Service Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Town County Registered Provider Telephone Number Service Type Conditions of Service Attached Little Buddies Preschool Knocknasna Abbeyfeale Limerick Clara Daly 085 7569865 Sessional Little Stars Creche Killarney Road Abbeyfeale Limerick Ann-Marie Huxley 068 30438 Full Day Catriona Sheeran Sandra 087 9951614/ Meenkilly Pre School Meenkilly National school Meenkilly Abbeyfeale Limerick Sessional Broderick 0879849039 Noreen Barry Playschool Community Centre New Street Abbeyfeale Limerick Noreen Barry 087 2499797 Sessional Teach Mhuire Montessori 12 Colbert Terrace Abbeyfeale Limerick Mary Barrett 086 3510775 Sessional Adare Playgroup Methodist Hall Adare Limerick Gillian Devery 085 7299151 Sessional Kilfinny School Childcare Kilfinny National School Kilfinny Adare Limerick Marion Geary 089 4196810 Part Time Little Gems Montessori Barley Grove Killarney Road Adare Limerick Veronica Coleman 061 355354 Sessional Tuogh Montessori School Tuogh Adare Limerick Geraldine Norris 085 8250860 Sessional Regulation 19 - Health, Karibu Montessori The Newtown Centre Annacotty Limerick Liza Eyres 061 338339 Full Day Welfare and Developmen t of Child Wilmot's Childcare Annacotty Business Park Annacotty Limerick Rosemary Wilmot 061 358166 Full Day Ardagh Montessori School Main Street Ardagh Limerick Martina McGrath 087 6814335 Sessional St. Coleman’s Childcare Kilcolman Community Creche Kilcolman Ardagh Limerick Joanna O'Connor 069 60770 Full Day Service Leaping Frogs Childminding Coolcappagh -

The Irish Working Class and the War of Independence

The Irish Working Class and the War of Independence Conor Kostick of rural workers battled white armies of the FFF (Farmers Freedom Force). In the west, where great tracts of land were still owned by absentee landlords, the struggle took the form of small farmers breaking up the large estates or in some cases appropriating them collectively and working them as soviets.1 Yet, of course, it was in the urban centres that the working class displayed the great- ‘Workers Soviet Mills, We Make Bread Not Profits’ est militancy and in addition to an almost continuous sequence of strikes and local gen- eral strikes there were five crucial turning points in these revolutionary years created In the coming centenary commemora- by urban working class activity: firstly, a tions of the Easter Rising of 1916 there will general strike against conscription; secondly, be a great deal of enthusiasm for the efforts a general strike at the beginning of 1919 in of that generation to escape the British Em- Belfast; thirdly, the Limerick Soviet of April pire. Yet nearly all the public attention and 1919; fourthly, in April 1920 a soviet take- memorial events will be directed to discus- over of the major towns of Ireland for the re- sion of the role of the senior figures of the na- lease of hunger strikers; and fifthly, through- tional movement. One of the most neglected out 1920, the refusal of transport workers to groups in the social memory of these years move British troops or army equipment. was the working class. Yet it was working class action above all that stymied British On 16 April 1918, with the passage of authority in Ireland. -

Fa-File-Pdf Limerick Leader Advert Re CPO Confirmation.Pdf 209.75 KB

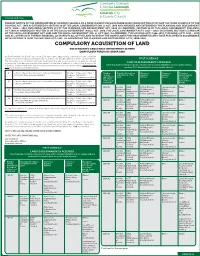

PUBLIC NOTICE FORM OF NOTICE OF THE CONFIRMATION BY AN BORD PLEANÁLA OF A COMPULSORY PURCHASE ORDER MADE UNDER SECTION 76 OF AND THE THIRD SCHEDULE TO THE HOUSING ACT, 1966 AS EXTENDED BY SECTION 10 OF THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT (NO. 2) ACT, 1960 AND AMENDED AND EXTENDED BY THE PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT ACTS, 2000 – 2019, INCLUDING SECTION 213 OF THE PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT ACT, 2000 (AS AMENDED), SECTION 10 OF THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT (IRELAND), ACT 1898 AS AMENDED BY SECTION 11 OF THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT (NO.2), ACT, 1960, THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACTS, 1925 – 2019, INCLUDING SECTIONS 11 AND 184 OF THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT, 2001 AND THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT (NO. 2), ACT 1960, (AS AMENDED), THE HOUSING ACTS 1966-2015, THE ROADS ACTS 1993 – 2015 AND ALL OTHER ACTS THEREBY ENABLING, AS RESPECTS ALL OF THE LAND TO WHICH THE COMPULSORY PURCHASE ORDER RELATES TO BE PUBLISHED IN ACCORDANCE WITH SECTION 78 (1) OF THE HOUSING ACT, 1966 , AS AMENDED BY THE PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT ACTS, 2000-2020 COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF LAND N20 O’ROURKE’S CROSS ROAD IMPROVEMENT SCHEME COMPULSORY PURCHASE ORDER 2020 An Bord Pleanála (“the Board”) has, on the 23rd day of April, 2021, made a confirmation order confirming the above-named compulsory purchase order as respects the land described in the First Schedule hereto. FIRST SCHEDULE The said order, as so confirmed, authorises the Limerick City and County Council to acquire the said land compulsorily. It will become operative three weeks from the date of publication of this notice. A copy of the LAND TO BE PERMANENTLY ACQUIRED -

What's the Matter with Ireland?

What's the Matter with Ireland? Ruth Russell Project Gutenberg's What's the Matter with Ireland?, by Ruth Russell This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: What's the Matter with Ireland? Author: Ruth Russell Release Date: April 15, 2004 [EBook #12033] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WHAT'S THE MATTER WITH IRELAND? *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, David Newman and PG Distributed Proofreaders What's the Matter with Ireland? By Ruth Russell 1920 TO MY MOTHER CONTENTS I. WHAT'S THE MATTER WITH IRELAND II. SINN FEIN AND REVOLUTION III. IRISH LABOR AND CLASS REVOLUTION IV. AE'S PEACEFUL REVOLUTION V. THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND COMMUNISM VI. WHAT ABOUT BELFAST? ELECTED GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF IRELAND (AMERICAN DELEGATION) January 29, 1920. _Miss Ruth' Russell, Chicago, Illinois_. Dear Miss Russell: I have read the advance copy of your book, "What's the Matter with Ireland?", with much interest. I congratulate you on the rapidity with which you succeeded in understanding Irish conditions and grasped the Irish viewpoint. I hope your book will be widely read. Your first chapter will be instructive to those who have been deceived by the recent cry of Irish prosperity. Cries of this sort are echoed without thought as to their truth, and gain credence as they pass from mouth to mouth. -

Information and Services for Older People Across Limerick

INFORMATION AND SERVICES FOR OLDER PEOPLE ACROSS LIMERICK 1 INFORMATION AND SERVICES FOR OLDER PEOPLE ACROSS LIMERICK CONTENTS USEFUL NUMBERS .............................................................................3 SECTION 1: BEING POSITIVE: ACTIVITIES INVOLVING OLDER PEOPLE Active Retired Group .............................................................................4 PROBUS ..............................................................................................5 Courses and Activities ........................................................................5 General Course Providers ....................................................................5 Computer Skills Courses .....................................................................6 Men’s Sheds .......................................................................................7 Women’s Groups ............................................................................... 9 Get Togethers and Craft Groups .......................................................10 Cards .................................................................................................10 Bingo .................................................................................................11 Music and Dancing ............................................................................12 Day Centres ......................................................................................13 Libraries ............................................................................................18 -

Type of Treatment Limerick City

Volume Supplied Organisation Name Scheme Code Scheme Name Supply Type Population Served (m3/day) Type Of Treatment Coagulation, clarification and Flocculation, Rapid Gravity filtration Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1001 Abbeyfeale PWS PWS 6892 2640 followed by Chlorination Coagulation, clarification and Flocculation, Rapid Gravity filtration followed by Chlorination, UV & Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1002 Adare PWS PWS 2498 1133 Fluoridation Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1003 Anglesboro PWS PWS 34 2 Chlorination & UV Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB2002 Ardpatrick Kilfinnane Public Water Supply PWS 1317 818 Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1007 Athlacca PWS PWS 130 26 Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1008 Ballingarry PWS PWS 994 504 Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1010 Ballylanders PWS PWS 620 164 Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1013 Bruff PWS PWS 1460 651 Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1014 Bruree PWS PWS 811 291 Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1015 Caherconlish PWS PWS 423 552 See clareville WTP & Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB2001 Cappamore Foileen Public Water Supply PWS 2456 949 Chlorination Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1019 Carrigkerry PWS PWS 275 108 Chlorination & UV Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1052 Carrigmore PWS PWS 372 89 Chlorination & UV Limerick City and County Council 1900PUB1022 Castletown/Ballyagran PWS PWS 1276 -

Burial Ground Caretakers and Cemetery Status

Burial Ground Burial Plot Purchase Time of Need or Burial Ground Name Caretaker's Name & Phone Number Open/Closed Advance Purchase Abbey Old, Ballyorgan Brian Henry 061-556442 Closed N/A Abington Denis Moore, Barrington's Bridge, Lisnagry 086-3679410 Open Time of Need Adamstown (Old) Brian Henry 061-556442 Closed N/A Anhid (Croom) Limerick City & County Council, Rathkeale Area Office 069-64505 Closed N/A Annagh Breda Moore, Clonkeen, Lisnagry, 061-386422 Closed N/A Ardagh Extension Brian Henry 061-556442 Open Time of Need Ardcanny (Mellon) Patrick Hevenor Jnr. Mountpleasant, Kildimo 087-6403050 Closed N/A Ardkilmartin Old, near Brian Henry 061-556442 Open Time of Need Ballygrennan Ardpatrick John Lynch, Bohernagore, Ardpatrick. 087-9916536 Open Time of Need Askeaton (Old & New) Patrick J. McCarthy, 28 Plunkett Road, Askeaton 087-0505358 Open Time of Need Athea Tony O'Halloran, Gortnagross, Athea 068-42164 or 087-2427219 Open Time of Need Athenasey Brian Henry 061-556442 Closed N/A Athlacca Joe Ring, Rathcannon, Kilmallock. 063-90042. 087-6854929 Open Time of Need Pat Sheehy, The Forge, Ballydonnell, Feohanagh 069-72319/085- Auglish New Open Time of Need 1235798 Pat Sheehy, The Forge, Ballydonnell, Feohanagh 069-72319/085- Auglish Old Closed N/A 1235798 Ballinaclough Limerick City & County Council 061-556442 Closed N/A Ballinakill, Kilfinny Limerick City & County Council, Rathkeale Area Office 069-64505 Closed N/A Ballinamona Brian Henry 061-556442 Closed N/A Ballinard, Herbertstown William Lavery, Rutagh, Herbertstown 061-385268 Closed N/A Ballingaddy (New) James Hennessy, Lisheen, Kilmallock 087-0508177 Open Advance Ballingaddy (Old) James Hennessy, Lisheen, Kilmallock 087-0508177 Closed N/A Ballingarry, Croom Limerick City & County Council, Rathkeale Area Office 069-64505 Closed N/A Ballingarry, near Ballylanders Brian Henry 061-556442 Closed N/A Ballinlough Mr. -

Forgotten Revolution: the Limerick Soviet of April 1919’

‘Forgotten Revolution: The Limerick Soviet of April 1919’ Notes for an illustrated talk by Liam Cahill at the Granary Library, Limerick 10th April 2019 Our story begins with a young man named Robert Byrne. He was born in Dublin on 28 November 1889 and was named after his father, Robert, a fitter by trade, from the North Strand. His mother was Annie Hurley, from Limerick and after his father died in 1907, the family moved to live at Town Wall Cottages. SLIDE 1 Robert Byrne Robert Byrne was employed as a telegraph operator in Limerick GPO and was elected as a delegate from the Post Office Clerks’ Association to Limerick United Trades and Labour Council. He joined the 2nd Limerick Battalion, Irish Volunteers, under the command of Peadar Dunne, a veteran of Easter Week 1916. Byrne had been under Special Branch observation since before the 1916 Rising. Just before Christmas 1918 he was elected Adjutant of the Second Battalion but the tolerance of the postal authorities had reached its limits. In January 1919, he was dismissed from the Post Office because of his Republican activities. 1 On New Year’s Eve 1918, a party of Royal Irish Constabulary had raided the family home in Town Wall Cottages. They found a revolver in a locker beside his bed and a military instruction manual in the kitchen. On January 13, 1919 the RIC arrested Byrne and charged him with possession of a revolver and ammunition and he was remanded in prison. For a short time after his imprisonment he refused to take food.