New Insights Into the Hercynian Orogeny, and Their Implications for the Paleozoic Hydrocarbon System in the Arabian Plate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geology and Structural Evolution of the Foss River-Deception Creek Area, Cascade Mountains, Washington

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF James William McDougall for the degree of Master of Science in Geology presented on Lune, icnct Title: GEOLOGY AND STRUCTURALEVOLUTION OF THE FOSS RIVER-DECEPTION CREEK AREA,CASCADE MOUNTAINS, WASHINGTOV, Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: Robert S. Yekis Southwest of Stevens Pass, Washington,immediately west of the crest of the Cascade Range, pre-Tertiaryrocks include the Chiwaukum Schist, dominantly biotite-quartzschist characterized by a polyphase metamorphic history,that correlates with schistose basement east of the area of study.Pre-Tertiary Easton Schist, dominated by graphitic phyllite, is principallyexposed in a horst on Tonga Ridge, however, it also occurs eastof the horst.Altered peridotite correlated to Late Jurassic IngallsComplex crops out on the western margin of the Mount Stuart uplift nearDeception Pass. The Mount Stuart batholith of Late Cretaceous age,dominantly granodiorite to tonalite, and its satellite, the Beck lerPeak stock, intrude Chiwaukum Schist, Easton Schist, andIngalls Complex. Tertiary rocks include early Eocene Swauk Formation, a thick sequence of fluviatile polymictic conglomerateand arkosic sandstone that contains clasts resembling metamorphic and plutonic basement rocks in the northwestern part of the thesis area.The Swauk Formation lacks clasts of Chiwaukum Schist that would be ex- pected from source areas to the east and northeast.The Oligocene (?) Mount Daniel volcanics, dominated by altered pyroclastic rocks, in- trude and unconformably overlie the Swauk Formation.The -

Seismic Investigation Ofthe Buried Horst Between the Jornada Del Muerto and Mesilla Ground-Water Basins Near Lascruces, Dona Ana County, New Mexico

SEISMIC INVESTIGATION OFTHE BURIED HORST BETWEEN THE JORNADA DEL MUERTO AND MESILLA GROUND-WATER BASINS NEAR LASCRUCES, DONA ANA COUNTY, NEW MEXICO SANAUGUST1N PASS/ FEET -5,500 FLUVIAL FACIES FLOOD-PLAIN DEPOSITS 3,000 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 97-4147 Prepared in cooperation with the CITY OF LAS CRUCES and the NEW MEXICO STATE ENGINEER OFFICE Albuquerque, New Mexico 1997 SEISMIC INVESTIGATION OF THE BURIED HORST BETWEEN THE JORNADA DEL MUERTO AND MESILLA GROUND-WATER BASINS NEAR LAS CRUCES, DONA ANA COUNTY, NEW MEXICO By Dennis G. Woodward and Robert G. Myers U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 97 4147 Prepared in cooperation with the CITY OF LAS CRUCES and the NEW MEXICO STATE ENGINEER OFFICE Albuquerque, New Mexico 1997 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Water Resources Division Box 25286 4501 Indian School Road NE, Suite 200 Denver, CO 80225-0286 Albuquerque, NM 87110-3929 CONTENTS Page Abstract.................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction -

Tectonic Features of the Precambrian Belt Basin and Their Influence on Post-Belt Structures

... Tectonic Features of the .., Precambrian Belt Basin and Their Influence on Post-Belt Structures GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 866 · Tectonic Features of the · Precambrian Belt Basin and Their Influence on Post-Belt Structures By JACK E. HARRISON, ALLAN B. GRIGGS, and JOHN D. WELLS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER X66 U N IT ED STATES G 0 V ERN M EN T P R I NT I N G 0 F F I C E, \VAS H I N G T 0 N 19 7 4 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 74-600111 ) For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. GO\·ernment Printing Office 'Vashington, D.C. 20402 - Price 65 cents (paper cO\·er) Stock Number 2401-02554 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract................................................. 1 Phanerozoic events-Continued Introduction . 1 Late Mesozoic through early Tertiary-Continued Genesis and filling of the Belt basin . 1 Idaho batholith ................................. 7 Is the Belt basin an aulacogen? . 5 Boulder batholith ............................... 8 Precambrian Z events . 5 Northern Montana disturbed belt ................. 8 Phanerozoic events . 5 Tectonics along the Lewis and Clark line .............. 9 Paleozoic through early Mesozoic . 6 Late Cenozoic block faults ........................... 13 Late Mesozoic through early Tertiary . 6 Conclusions ............................................. 13 Kootenay arc and mobile belt . 6 References cited ......................................... 14 ILLUSTRATIONS Page FIGURES 1-4. Maps: 1. Principal basins of sedimentation along the U.S.-Canadian Cordillera during Precambrian Y time (1,600-800 m.y. ago) ............................................................................................... 2 2. Principal tectonic elements of the Belt basin reentrant as inferred from the sedimentation record ............ -

Post-Collisional Formation of the Alpine Foreland Rifts

Annales Societatis Geologorum Poloniae (1991) vol. 61:37 - 59 PL ISSN 0208-9068 POST-COLLISIONAL FORMATION OF THE ALPINE FORELAND RIFTS E. Craig Jowett Department of Earth Sciences, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario Canada N2L 3G1 Jowett, E. C., 1991. Post-collisional formation of the Alpine foreland rifts. Ann. Soc. Geol. Polon., 6 1 :37-59. Abstract: A series of Cenozoic rift zones with bimodal volcanic rocks form a discontinuous arc parallel to the Alpine mountain chain in the foreland region of Europe from France to Czechos lovakia. The characteristics of these continental rifts include: crustal thinning to 70-90% of the regional thickness, in cases with corresponding lithospheric thinning; alkali basalt or bimodal igneous suites; normal block faulting; high heat flow and hydrothermal activity; regional uplift; and immature continental to marine sedimentary rocks in hydrologically closed basins. Preceding the rifting was the complex Alpine continental collision orogeny which is characterized by: crustal shortening; thrusting and folding; limited calc-alkaline igneous activity; high pressure metamorphism; and marine flysch and continental molasse deposits in the foreland region. Evidence for the direction of subduction in the central area is inconclusive, although northerly subduction likely occurred in the eastern and western Tethys. The rift events distinctly post-date the thrusthing and shortening periods of the orogeny, making “impactogen” models of formation untenable. However, the succession of tectonic and igneous events, the geophysical characteristics, and the timing and location of these rifts are very similar to those of the Late Cenozoic Basin and Range province in the western USA and the Early Permian Rotliegendes troughs in Central Europe. -

A Fundamental Precambrian–Phanerozoic Shift in Earth's Glacial

Tectonophysics 375 (2003) 353–385 www.elsevier.com/locate/tecto A fundamental Precambrian–Phanerozoic shift in earth’s glacial style? D.A.D. Evans* Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, P.O. Box 208109, 210 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, CT 06520-8109, USA Received 24 May 2002; received in revised form 25 March 2003; accepted 5 June 2003 Abstract It has recently been found that Neoproterozoic glaciogenic sediments were deposited mainly at low paleolatitudes, in marked qualitative contrast to their Pleistocene counterparts. Several competing models vie for explanation of this unusual paleoclimatic record, most notably the high-obliquity hypothesis and varying degrees of the snowball Earth scenario. The present study quantitatively compiles the global distributions of Miocene–Pleistocene glaciogenic deposits and paleomagnetically derived paleolatitudes for Late Devonian–Permian, Ordovician–Silurian, Neoproterozoic, and Paleoproterozoic glaciogenic rocks. Whereas high depositional latitudes dominate all Phanerozoic ice ages, exclusively low paleolatitudes characterize both of the major Precambrian glacial epochs. Transition between these modes occurred within a 100-My interval, precisely coeval with the Neoproterozoic–Cambrian ‘‘explosion’’ of metazoan diversity. Glaciation is much more common since 750 Ma than in the preceding sedimentary record, an observation that cannot be ascribed merely to preservation. These patterns suggest an overall cooling of Earth’s longterm climate, superimposed by developing regulatory feedbacks -

Insights on the Crustal Evolution of the West African (Raton from Hf Isotopes in Detrital Zircons from the Anti-Atlas Belt

Insights on the crustal evolution of the West African (raton from Hf isotopes in detrital zircons from the Anti-Atlas belt a b c d b ]acobo Abati ,., Abdel Mohsine Aghzer , 1 , Axel Gerdes , ,2, Nasser Ennih • Departamento de Petrologfa y Geoquimica and Instituto de Geologia Econ6mica, Universidad Comp!utense/Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas. 28040 Madrid, Spain b Departament Ge% gie. Faculte des Sciences, Universite Chouaib Doukkali, EIJadida. Morocco c InstitutftirGeowissenschaften. Minera/ogie, Goethe-UniversityFrankfurt (GUF),Altenhoferallee 1. D-60438 Frankfurt amMain, Gennany d Department of Earth Sciences, SteIIenbosch University.Private BagXl. Matieland 7602, South Africa ABSTRACT The Lu-Hf isotopic composition of detrital zircons has been used to investigate the crustal evolution of the northern part of the West African (raton (WAC). The zircons were separated from six samples of siliciclastic sedimentary rocks from the main Neoproterozic stratigraphic units of the Anti-Atlas belt, from the SiIWa and Zenaga inliers. The data suggest that the north part of the WAC formed during three cycles of juvenile crust formation with variable amount of reworking of older crust. The younger group of zircons, with a main population clustering around 610 Ma, has a predominant juvenile character and Keyworili: evidences of moderate mixing with Paleoproterozoic and Neoarchean crust, which supports that most Anti-Atlas belt igneous and metamorphic rocks where zircons originally crystallized were formed in an ensialic mag Morocco Hfisotopes matic arc environment. The group of zircons in the age range 1.79-2.3 Ca corresponds to the major crust Detrital zircon forming event in the WAC: the Eburnian orogeny. -

Collision Orogeny

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on October 6, 2021 PROCESSES OF COLLISION OROGENY Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on October 6, 2021 Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on October 6, 2021 Shortening of continental lithosphere: the neotectonics of Eastern Anatolia a young collision zone J.F. Dewey, M.R. Hempton, W.S.F. Kidd, F. Saroglu & A.M.C. ~eng6r SUMMARY: We use the tectonics of Eastern Anatolia to exemplify many of the different aspects of collision tectonics, namely the formation of plateaux, thrust belts, foreland flexures, widespread foreland/hinterland deformation zones and orogenic collapse/distension zones. Eastern Anatolia is a 2 km high plateau bounded to the S by the southward-verging Bitlis Thrust Zone and to the N by the Pontide/Minor Caucasus Zone. It has developed as the surface expression of a zone of progressively thickening crust beginning about 12 Ma in the medial Miocene and has resulted from the squeezing and shortening of Eastern Anatolia between the Arabian and European Plates following the Serravallian demise of the last oceanic or quasi- oceanic tract between Arabia and Eurasia. Thickening of the crust to about 52 km has been accompanied by major strike-slip faulting on the rightqateral N Anatolian Transform Fault (NATF) and the left-lateral E Anatolian Transform Fault (EATF) which approximately bound an Anatolian Wedge that is being driven westwards to override the oceanic lithosphere of the Mediterranean along subduction zones from Cephalonia to Crete, and Rhodes to Cyprus. This neotectonic regime began about 12 Ma in Late Serravallian times with uplift from wide- spread littoral/neritic marine conditions to open seasonal wooded savanna with coiluvial, fluvial and limnic environments, and the deposition of the thick Tortonian Kythrean Flysch in the Eastern Mediterranean. -

Estimation of Spatiotemporal Isotropic and Anisotropic Myocardial Stiffness Using

Estimation of Spatiotemporal Isotropic and Anisotropic Myocardial Stiffness using Magnetic Resonance Elastography: A Study in Heart Failure DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ria Mazumder, M.S. Graduate Program in Electrical and Computer Engineering The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Bradley Dean Clymer, Advisor Dr. Arunark Kolipaka, Co-Advisor Dr. Patrick Roblin Dr. Richard D. White © Copyright by Ria Mazumder 2016 Abstract Heart failure (HF), a complex clinical syndrome that is characterized by abnormal cardiac structure and function; and has been identified as the new epidemic of the 21st century [1]. Based on the left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF), HF can be classified into two broad categories: HF with reduced EF (HFrEF) and HF with preserved EF (HFpEF). Both HFrEF and HFpEF are associated with alteration in myocardial stiffness (MS), and there is an extensively rich literature to support this relation. However, t0 date, MS is not widely used in the clinics for the diagnosis of HF precisely because of the absence of a clinically efficient tool to estimate MS. Current clinical techniques used to measure MS are invasive in nature, provide global stiffness measurements and cannot assess the true intrinsic properties of the myocardium. Therefore, there is a need to non-invasively quantify MS for accurate diagnosis and prognosis of HF. In recent years, a non-invasive technique known as cardiac magnetic resonance elastography (cMRE) has been developed to estimate MS. However, most of the reported studies using cMRE have been performed on phantoms, animals and healthy volunteers and minimal literature recognizing the importance of cMRE in diagnosing disease conditions, especially with respect to HF is available. -

Sa˜O Luıs Craton and Gurupi Belt (Brazil)

Sa˜o Luı´s Craton and Gurupi Belt (Brazil): possible links with the West African Craton and surrounding Pan-African belts E. L. KLEIN1,2 & C. A. V. MOURA3 1CPRM (Companhia de Pesquisa de Recursos Minerais)/Geological Survey of Brazil, Av. Dr. Freitas, 3645, Bele´m-PA, CEP 66095-110, Brazil (e-mail: [email protected]) 2Researcher at CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientı´fico e Tecnolo´gico) 3Laborato´rio de Geologia Isoto´pica/Para´-Iso, Universidade Federal do Para´, Centro de Geocieˆncias, CP 1611, Bele´m-PA, Brazil, CEP 66075-900 Abstract: The Sa˜o Luı´s Craton and the Palaeoproterozoic basement rocks of the Neoproterozoic Gurupi Belt in northern Brazil are part of an orogen having an early accretionary phase at 2240– 2150 Ma and a late collisional phase at 2080 + 20 Ma. Geological, geochronological and isotopic evidence, along with palaeogeographic reconstructions, strongly suggest that these Brazilian terrains were contiguous with the West African Craton in Palaeoproterozoic times, and that this landmass apparently survived subsequent continental break-up until its incorporation in Rodinia. The Gurupi Belt is an orogen developed in the southern margin of the West African–Sa˜o Luı´s Craton at c. 750–550 Ma, after the break up of Rodinia. Factors such as present-day and possible past geographical positions, the timing of a few well-characterized events, the structural polarity and internal structure of the belt, in addition to other indirect evidence, all favour correlation between the Gurupi Belt and other Brasiliano/Pan-African belts, especially the Me´dio Coreau´ domain of the Borborema Province and the Trans-Saharan Belt of Africa, despite the lack of proven physical links between them. -

4. Deep-Tow Observations at the East Pacific Rise, 8°45N, and Some Interpretations

4. DEEP-TOW OBSERVATIONS AT THE EAST PACIFIC RISE, 8°45N, AND SOME INTERPRETATIONS Peter Lonsdale and F. N. Spiess, University of California, San Diego, Marine Physical Laboratory, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, California ABSTRACT A near-bottom survey of a 24-km length of the East Pacific Rise (EPR) crest near the Leg 54 drill sites has established that the axial ridge is a 12- to 15-km-wide lava plateau, bounded by steep 300-meter-high slopes that in places are large outward-facing fault scarps. The plateau is bisected asymmetrically by a 1- to 2-km-wide crestal rift zone, with summit grabens, pillow walls, and axial peaks, which is the locus of dike injection and fissure eruption. About 900 sets of bottom photos of this rift zone and adjacent parts of the plateau show that the upper oceanic crust is composed of several dif- ferent types of pillow and sheet lava. Sheet lava is more abundant at this rise crest than on slow-spreading ridges or on some other fast- spreading rises. Beyond 2 km from the axis, most of the plateau has a patchy veneer of sediment, and its surface is increasingly broken by extensional faults and fissures. At the plateau's margins, secondary volcanism builds subcircular peaks and partly buries the fault scarps formed on the plateau and at its boundaries. Another deep-tow survey of a patch of young abyssal hills 20 to 30 km east of the spreading axis mapped a highly lineated terrain of inactive horsts and grabens. They were created by extension on inward- and outward- facing normal faults, in a zone 12 to 20 km from the axis. -

Grand Canyon

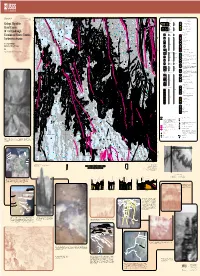

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

Joints, Folds, and Faults

Structural Geology Rocks in the Crust Are Bent, Stretched, and Broken … …by directed stresses that cause Deformation. Types of Differential Stress Tensional, Compressive, and Shear Strain is the change in shape and or volume of a rock caused by Stress. Joints, Folds, and Faults Strain occurs in 3 stages: elastic deformation, ductile deformation, brittle deformation 1 Type of Strain Dependent on … • Temperature • Confining Pressure • Rate of Strain • Presence of Water • Composition of the Rock Dip-Slip and Strike-Slip Faults Are the Most Common Types of Faults. Major Fault Types 2 Fault Block Horst and Graben BASIN AND Crustal Extension Formed the RANGE PROVINCE Basin and Range Province. • Decompression melting and high heat developed above a subducted rift zone. • Former margin of Farallon and Pacific plates. • Thickening, uplift ,and tensional stress caused normal faults. • Horst and Graben structures developed. Fold Terminology 3 Open Anticline – convex upward arch with older rocks in the center of the fold (symmetrical) Isoclinal Asymmetrical Overturned Recumbent Evolution Simple Folds of a fold into a reverse fault An eroded anticline will have older beds in the middle An eroded syncline will have younger beds in middle Outcrop patterns 4 • The Strike of a body of rock is a line representing the intersection of A layer of tilted that feature with the plane of the horizon (always measured perpendicular to the Dip). rock can be • Dip is the angle below the horizontal of a geologic feature. represented with a plane. o 30 The orientation of that plane in space is defined with Strike-and- Dip notation. Maps are two- Geologic Map Showing Topography, Lithology, and dimensional Age of Rock Units in “Map View”.