A Revised List of the Birds of Southwestern California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ASSESSMENT of COASTAL WATER RESOURCES and WATERSHED CONDITIONS at CHANNEL ISLANDS NATIONAL PARK, CALIFORNIA Dr. Diana L. Engle

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-2006/354 Water Resources Division Natural Resource Program Centerent of the Interior ASSESSMENT OF COASTAL WATER RESOURCES AND WATERSHED CONDITIONS AT CHANNEL ISLANDS NATIONAL PARK, CALIFORNIA Dr. Diana L. Engle The National Park Service Water Resources Division is responsible for providing water resources management policy and guidelines, planning, technical assistance, training, and operational support to units of the National Park System. Program areas include water rights, water resources planning, marine resource management, regulatory guidance and review, hydrology, water quality, watershed management, watershed studies, and aquatic ecology. Technical Reports The National Park Service disseminates the results of biological, physical, and social research through the Natural Resources Technical Report Series. Natural resources inventories and monitoring activities, scientific literature reviews, bibliographies, and proceedings of technical workshops and conferences are also disseminated through this series. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the National Park Service. Copies of this report are available from the following: National Park Service (970) 225-3500 Water Resources Division 1201 Oak Ridge Drive, Suite 250 Fort Collins, CO 80525 National Park Service (303) 969-2130 Technical Information Center Denver Service Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225-0287 Cover photos: Top Left: Santa Cruz, Kristen Keteles Top Right: Brown Pelican, NPS photo Bottom Left: Red Abalone, NPS photo Bottom Left: Santa Rosa, Kristen Keteles Bottom Middle: Anacapa, Kristen Keteles Assessment of Coastal Water Resources and Watershed Conditions at Channel Islands National Park, California Dr. Diana L. -

Than a Meal: the Turkey in History, Myth

More Than a Meal Abigail at United Poultry Concerns’ Thanksgiving Party Saturday, November 22, 1997. Photo: Barbara Davidson, The Washington Times, 11/27/97 More Than a Meal The Turkey in History, Myth, Ritual, and Reality Karen Davis, Ph.D. Lantern Books New York A Division of Booklight Inc. Lantern Books One Union Square West, Suite 201 New York, NY 10003 Copyright © Karen Davis, Ph.D. 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of Lantern Books. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data For Boris, who “almost got to be The real turkey inside of me.” From Boris, by Terry Kleeman and Marie Gleason Anne Shirley, 16-year-old star of “Anne of Green Gables” (RKO-Radio) on Thanksgiving Day, 1934 Photo: Underwood & Underwood, © 1988 Underwood Photo Archives, Ltd., San Francisco Table of Contents 1 Acknowledgments . .9 Introduction: Milton, Doris, and Some “Turkeys” in Recent American History . .11 1. A History of Image Problems: The Turkey as a Mock Figure of Speech and Symbol of Failure . .17 2. The Turkey By Many Other Names: Confusing Nomenclature and Species Identification Surrounding the Native American Bird . .25 3. A True Original Native of America . .33 4. Our Token of Festive Joy . .51 5. Why Do We Hate This Celebrated Bird? . .73 6. Rituals of Spectacular Humiliation: An Attempt to Make a Pathetic Situation Seem Funny . .99 7 8 More Than a Meal 7. -

Birds on San Clemente Island, As Part of Our Work Toward the Recovery of the Island’S Endangered Species

WESTERN BIRDS Volume 36, Number 3, 2005 THE BIRDS OF SAN CLEMENTE ISLAND BRIAN L. SULLIVAN, PRBO Conservation Science, 4990 Shoreline Hwy., Stinson Beach, California 94970-9701 (current address: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 159 Sapsucker Woods Rd., Ithaca, New York 14850) ERIC L. KERSHNER, Institute for Wildlife Studies, 2515 Camino del Rio South, Suite 334, San Diego, California 92108 With contributing authors JONATHAN J. DUNN, ROBB S. A. KALER, SUELLEN LYNN, NICOLE M. MUNKWITZ, and JONATHAN H. PLISSNER ABSTRACT: From 1992 to 2004, we observed birds on San Clemente Island, as part of our work toward the recovery of the island’s endangered species. We increased the island’s bird list to 317 species, by recording many additional vagrants and seabirds. The list includes 20 regular extant breeding species, 6 species extirpated as breeders, 5 nonnative introduced species, and 9 sporadic or newly colonizing breeding species. For decades San Clemente Island had been ravaged by overgrazing, especially by goats, which were removed completely in 1993. Since then, the island’s vegetation has begun recovering, and the island’s avifauna will likely change again as a result. We document here the status of that avifauna during this transitional period of re- growth, between the island’s being largely denuded of vegetation and a more natural state. It is still too early to evaluate the effects of the vegetation’s still partial recovery on birds, but the beginnings of recovery may have enabled the recent colonization of small numbers of Grasshopper Sparrows and Lazuli Buntings. Sponsored by the U. S. Navy, efforts to restore the island’s endangered species continue—among birds these are the Loggerhead Shrike and Sage Sparrow. -

Scripps's Murrelet and Cassin's Auklet Reproductive Monitoring and Restoration Activities on Santa Barbara Island, Californi

Scripps’s Murrelet and Cassin’s Auklet Reproductive Monitoring and Restoration Activities on Santa Barbara Island, California in 2014 James A. Howard1, Samantha M. Cady1, David Mazurkiewicz2, Andrew A. Yamagiwa1, Catherine A. Carter1, Eden F.W. Wynd1, Nicholas B. Hernandez1, Carolyn L. Mills1, Amber M. Lessing1 1California Institute of Environmental Studies 3408 Whaler Avenue Davis, CA 95616 2Channel Islands National Park 1901 Spinnaker Drive Ventura, CA 93001 September 24, 2015 Suggested citation: Howard, J.A., S.M. Cady, D.M. Mazurkiewicz, A.A. Yamagiwa, C.A. Carter, E.F.W. Wynd, N.B. Hernandez, C.L. Mills, A.M. Lessing. 2015. Scripps’s Murrelet and Cassin’s Auklet Reproductive Monitoring and Restoration Activities on Santa Barbara Island, California in 2014. Unpublished report. California Institute of Environmental Studies.40 pages. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY California Institute of Environmental Studies, partnering with the National Park Service, has been actively restoring the native shrub habitat of Santa Barbara Island since 2007, as funded by the Montrose Settlements Restoration Program. The goals of this project are to increase the amount of nesting habitat for Scripps’s Murrelet (Synthliborhamphus scrippsi) and restore an historic nesting colony of Cassin’s Auklet (Ptychoramphus aleuticus). This effort has resulted in approximately 7.7 acres of restored habitat on the island, utilizing nearly 30,000 island-sourced native plants. In the 2014 nesting season, 186 Scripps’s Murrelet clutches in 141 active nest sites were monitored on Santa Barbara Island. We could reliably determine the fates for 182 nests. Nesting data were collected at five plots in 2014: Arch Point North Cliffs, Bunkhouse, Cat Canyon, Landing Cove, and the Landing Cove Dock. -

Cop16 Prop. 57

Original language: English CoP16 Prop. 57 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Sixteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Bangkok (Thailand), 3-14 March 2013 CONSIDERATION OF PROPOSALS FOR AMENDMENT OF APPENDICES I AND II A. Proposal Delist Dudleya stolonifera and Dudleya traskiae from Appendix II. B. Proponent United States of America*. C. Supporting statement 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Magnoliopsida 1.2 Order: Saxifragales 1.3 Family: Crassulaceae 1.4 Genus and species, including author and year: a) Dudleya stolonifera Moran 1950 b) Dudleya traskiae (Rose) Moran 1942 1.5 Scientific synonyms: b) Stylophyllum traskiae Rose; Echeveria traskiae (Rose) A. Berger 1.6 Common names: English: a) Laguna Beach live-forever; Laguna Beach dudleya b) Santa Barbara Island live-forever; Santa Barbara Island dudleya French: Spanish: 1.7 Code numbers: None 2. Overview At the fourth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to CITES (CoP4; Gaborone, 1983), the United States of America proposed Dudleya stolonifera and Dudleya traskiae to be included in Appendix I (CoP4 Prop. 138 and Prop. 139), which were adopted by the Parties. At the ninth meeting of the Plants Committee (PC9; Darwin, 1999), the two species were reviewed under the Periodic Review of the Appendices, and were subsequently recommended for transfer from Appendix I to Appendix II. Dudleya stolonifera and D. traskiae were transferred to Appendix II at CoP11 (Gigiri, 2000) and CoP12 (Santiago, 2002), respectively. The species are the only Dudleya species listed in the CITES Appendices. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat or the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

The Big Year Ebook Free Download

THE BIG YEAR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mark Obmascik | 320 pages | 08 Dec 2011 | Transworld Publishers Ltd | 9780857500694 | English | London, United Kingdom The Big Year PDF Book Pete Shackelford Steve Darling Archived from the original on January 26, In , Nicole Koeltzow reached the species milestone on July 1, while in August Gaylee and Richard Dean became the first birders to reach species in consecutive years. Highway runs along the California Coast. Crazy Credits. By Noah Strycker July 26, Stu is hiking with his toddler grandson already enamored by birds in the Rockies. Mary Swit Calum Worthy Miller Greg Miller It also replaces Jack Black's narration of the story with a new narration by John Cleese who also receives a credit in the opening title sequence. Narrator voice Jack Black Brad is a skilled birder who can identify nearly any species solely by sound. Category:Birds and humans Zoomusicology. Added to Watchlist. Retrieved January 25, Get Audubon in Your Inbox Let us send you the latest in bird and conservation news. Retrieved Jessica Steve Martin Paul Lavigne Heather Osborne Share this page:. Birds class : Aves. Yukon News. Tony Cindy Busby Wheel of Fortune Underscore. Visit our What to Watch page. Caprimulgiformes nightjars and relatives Steatornithiformes Podargiformes Apodiformes swifts and hummingbirds. In , an unprecedented four birders attempted simultaneous ABA Area big years. Steve's character provides fatherly guidance and support that helps Jack Black's character move forward with his life and relationships. The company is in the middle of complicated negotiations to merge with a competitor, so his two anointed successors keep calling him back to New York for important meetings; to some extent he is a prisoner of his own success. -

An Assessment of the Risk Associated with the Movement Turkeys To

United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Veterinary Services Science, Technology, An Assessment of the Risk Associated with the and Analysis Services Movement Turkeys to Market Into, Within, and Center for Epidemiology and Animal Health Out of a Control Area During a Highly 2150 Centre Avenue Pathogenic Avian Influenza Outbreak in the Building B Fort Collins, CO 80526 United States March 2017 FIRST DRAFT September 2017 SECOND REVIEW January 2018 THIRD REVIEW October 2018 FINAL REVIEW AND CLEARANCE A Collaboration between the Turkey Sector Working Group, the University of Minnesota’s Secure Food Systems Team, and USDA:APHIS:VS:CEAH UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE ANIMAL AND PLANT HEALTH INSPECTION SERVICE VETERINARY SERVICES CENTER FOR EPIDEMIOLOGY AND ANIMAL HEALTH Turkeys to Market Risk Assessment Suggested bibliographic citation for this report: Carol Cardona, Carie Alexander, Justin Bergeron, Peter Bonney, Marie Culhane, Timothy Goldsmith, David Halvorson, Eric Linskens, Sasidhar Malladi, Amos Ssematimba, Emily Walz, Todd Weaver, Jamie Umber. An Assessment of the Risk Associated with the Movement of Turkeys to Market Into, Within, and Out of a Control Area during a Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Outbreak in the United States. Collaborative agreement between USDA:APHIS:VS and University of Minnesota Center for Secure Food Systems. Fort Collins, CO. October 2018. 217 pgs. This document was developed through the Continuity of Business / Secure Food Supply Plans / Secure Poultry Supply -

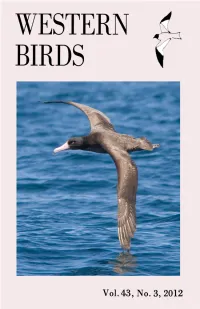

Western Birds-43(3)-Webcomp.Pdf

Volume 43, Number 3, 2012 Fall Bird Migration on Santa Barbara Island, California Nick Lethaby, Wes Fritz, Paul W. Collins, and Peter Gaede.......118 A Population Census of the Cactus Wren in Coastal Los Angeles County Daniel S. Cooper, Robert A. Hamilton, and Shannon D. Lucas .............................................................151 The 36th Annual Report of the California Bird Records Committee: 2010 Records Oscar Johnson, Brian L. Sullivan, and Guy McCaskie ...................................................................164 NOTES Snowy Plover Buried Alive by Wind-Blown Sand J. Daniel Farrar, Adam A. Kotaich, David J. Lauten, Kathleen A. Castelein, and Eleanor P. Gaines ..............................................................189 In Memoriam: Clifford R. Lyons Jon Winter .................................192 Featured Photo: Multiple Color Abnormalities in a Wintering Mew Gull Jeff N. Davis and Len Blumin ................................193 Front cover photo by © Robert H. Doster of Chico, California: Short-tailed Albatross (Phoebastria albatrus), offshore of Ft. Bragg, Mendocino County, California, 20 May 2012. Since the species was brought to the brink of extinction in the 1930s, it has recovered to the point where small numbers are seen regularly in the northeastern Pacific and one pair colonized Midway Atoll, fledging young in 2011 and 2012. Back cover: “Featured Photo” by © Len Blumin of Mill Valley, California: Aberrant Mew Gull (Larus canus) at Las Gallinas wastewater ponds in Terra Linda, Marin County, California, -

Island Views Volume 3, 2005 — 2006

National Park Service Park News U.S. Department of the Interior The official newspaper of Channel Islands National Park Island Views Volume 3, 2005 — 2006 Tim Hauf, www.timhaufphotography.com Foxes Returned to the Wild Full Circle In OctobeR anD nOvembeR 2004, The and November 2004, an additional 13 island Chumash Cross Channel in Tomol to Santa Cruz Island National Park Service (NPS) released 23 foxes on Santa Rosa and 10 on San Miguel By Roberta R. Cordero endangered island foxes to the wild from were released to the wild. The foxes will be Member and co-founder of the Chumash Maritime Association their captive rearing facilities on Santa Rosa returned to captivity if three of the 10 on The COastal portion OF OuR InDIg- and San Miguel Islands. Channel Islands San Miguel or five of the 13 foxes on Santa enous homeland stretches from Morro National Park Superintendent Russell Gal- Rosa are killed or injured by golden eagles. Bay in the north to Malibu Point in the ipeau said, “Our primary goal is to restore Releases from captivity on Santa Cruz south, and encompasses the northern natural populations of island fox. Releasing Island will not occur this year since these Channel Islands of Tuqan, Wi’ma, Limuw, foxes to the wild will increase their long- foxes are thought to be at greater risk be- and ‘Anyapakh (San Miguel, Santa Rosa, term chances for survival.” cause they are in close proximity to golden Santa Cruz, and Anacapa). This great, For the past five years the NPS has been eagle territories. -

2002 Volume Visit Us At: Visit

PM 6.5 / TEMPLATE VERSION 7/15/97 - OUTPUT BY - DATE/TIME C W H A L E W A T C H I N G M Y K The waters surrounding Channel Islands National Park Whether you are C are home to many diverse and beautiful species of cetaceans watching from shore or M (whales, dolphins and porpoises). About one third of the in a boat, here are a Y few distinctive habits K cetacean species found worldwide can be seen right here in IslandIsland ViewsViews C our own backyard, the Santa Barbara Channel. The 27 to look for: M species sighted in the channel include gray, blue, humpback, Brad Sillasen Spouts. Your first Y minke, sperm and pilot whales; orcas; Dall’s porpoise; and indication of a whale K Blue whale Risso’s, Pacific white- will probably be its spout or “blow.” It will be visible for many miles on a calm sided, common and Bill Faulkner day, and an explosive “whoosh” of exhalation may be heard bottlenose dolphins. Watching humpback whales. This diversity of up to 1/2 mile away. The spout is mainly condensation cetacean species offers a created as the whale’s warm, humid breath expands and cools Many whales are on the endangered species list and should A Visitor’s Guide to Channel Islands National Park Volume 2, 2001-2002 great opportunity to in the sea air. be treated with special care. All whales are protected by F O R W A R D T O T H E P A S T NPS whale watch year-round. -

Sunday, January 01, 2017 7:00 AM (Time Tentative) 0452-Angeles Chp Hundred Peaks Outing I: Chuckwalla Mtn (5029') and Cross Mountain (5203')

2/11/2018 Sierra Club Activities Sunday, January 01, 2017 7:00 AM (Time Tentative) 0452-Angeles Chp Hundred Peaks Outing I: Chuckwalla Mtn (5029') and Cross Mountain (5203') Peter H Doggett 818-840-8748 [email protected] Ignacia Doggett 818-840-8748 [email protected] I: Chuckwalla Mtn (5029') and Cross Mountain (5203') - Start the New Year with a loop hike that will be about 10 miles round trip with 4,000' of gain. Please bring liquids, lugsoles, layers, lunch and hat. Contact [email protected] for trip details. Leaders Peter & Ignacia Doggett Wednesday, January 04, 2017 7:00 AM 0452-Angeles Chp Hundred Peaks Outing I: Red Mountain (5261') and Black Mountain #6 (5244') Bill Simpson 323-683-0959 [email protected] Virginia Simpson 323-683-0959 [email protected] Jimmy Quan 626-441-8843 [email protected] May Tang 562-809-0809 [email protected] Michael D Dillenback 310-378-7495 [email protected] Jim Hagar 818-468-6451 [email protected] I: Red Mountain (5261') and Black Mountain #6 (5244') - Join us for two special peaks in the desert north of the town of Mojave. Drive between trailheads. Totals for the day will be about 8 miles and around 3100' of gain. High-clearance vehicles necessary. Please bring water, hiking footwear, layers, lunch, sunblock and hat. Contact Leader for details. Leader: BILL SIMPSON Co-Leaders: VIRGINIA SIMPSON, JIMMY QUAN, MAY TANG, MIKE DILLENBACK, JIM HAGAR Saturday, January 07, 2017 to Sunday, January 08, 2017 0452-Angeles Chp Hundred Peaks Outing I: Stepladder Mountains (2,927'), Old Woman Mountain (5,325') Mat Kelliher 818-667-2490 [email protected] Bill Simpson 323-683-0959 [email protected] I: Stepladder Mountains (2,927'), Old Woman Mountain (5,325') – Join us for a fun weekend way out in eastern California near Needles, CA as we climb a couple of classic desert peaks along the botanical transition zone between the Mojave and Colorado Deserts. -

Wild Turkey Population History and Overview

Wild Turkey Population History and Overview Natural history The North American wild turkey (Melaeagris gallopavo) and the ocellated turkey (M. ocellata) of Mexico are the only two species of wild turkey extant in the world today. Taxonomically, they belong to the order Galliformes, family Phasianidae, and subfamily Meleagridinae [1]. Six geographic subspecies of the North American wild turkey are recognized [2]. The eastern subspecies (M. g. silvestris) occupies roughly the eastern half of the United States and parts of southeastern Canada. The Florida wild turkey or Osceola subspecies (M. g. osceola) inhabits the Florida peninsula south of the Suwannee River. In the western half of the continent, the Merriam’s wild turkey (M. g. merriami) occupies much of the intermountain West, and the Rio Grande turkey (M. g. intermedia) is found primarily in the plains states of the central United States and the northeastern Mexican states. The fifth subspecies, the Gould’s wild turkey (M. g. mexicana), is found in southeastern Arizona, southwestern New Mexico, and in the Sierra Madre Occidental Mountains of Mexico. The sixth subspecies, the Mexican wild turkey (M.g. gallopavo) is now thought to be extinct. It is from this subspecies that all domestic turkeys are believed to descend; a livestock species that in 2012 provided nearly 5.75 billion kg of meat to markets worldwide [3,4]. Historic decline Pre-Columbian populations of wild turkeys in the United States were conservatively estimated at 10 million animals [6] and they were an important resource for Native Americans who used the animals for food, clothing, tools, and ceremonial purposes [2,6].