POST-TRAUMATIC GROWTH: a HERO's JOURNEY Jenny Simpson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B. Moore Track & C. Maddox Field House

B. Moore Track & C. Maddox Field House - Site License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 5:57 PM 4/27/2019 Page 1 2019 LSU Invitational - 4/27/2019 Bernie Moore Stadium Results - Saturday Event 3 Women 3000 Meter Steeplechase Event 2 Men 4x100 Meter Relay Final Final Stadium: 9:45.94 s 2002 Michaela Manova Stadium: 38.32 s 2002 LSU LSU: 10:18.54 L 2001 Susanne Strunz Stadium: 38.32 c 1987 TCU Collegiate: 9:24.41 C 6/11/2016 Courtney Frerichs LSU: 38.24 L 1998 LSU Name Yr School Finals J. Grant, M, Alridge, B. Logan, C. Perry Finals Collegiate: 38.17 C 6/8/2018 Houston 1 Caroline Brooks JR Alabama 11:05.00 J Lewis, E. Hall, M. Burke, C. Burrell 44.850 (44.850) 2:08.220 (1:23.370) 3:34.322 (1:26.102) Team Relay Finals 5:02.104 (1:27.782) 6:32.697 (1:30.593) 8:04.340 (1:31.643) Finals 9:36.644 (1:32.304) 11:05.000 (1:28.356) 1 LSU A 39.04 2 Alicia Stamey SO LSU 11:23.55 2 Ole Miss A 40.36 45.457 (45.457) 2:09.446 (1:23.989) 3:36.173 (1:26.727) 3 UL-Lafayette A 41.56 5:05.367 (1:29.194) 6:36.794 (1:31.427) 8:11.467 (1:34.673) Event 13 Women 1500 Meter Run 9:50.154 (1:38.687) 11:23.545 (1:33.392) Final Event 4 Men 3000 Meter Steeplechase Stadium: 4:09.85 s 1987 Suzy Favor Final LSU: 4:17.14 L 1985 Christine Slythe Stadium: 8:22.34 s 2002 Daniel Lincoln Collegiate: 3:59.90 C 2009 Jenny Simpson LSU: 8:38.14 L 1990 Magnus Bengtsson Name Yr School Finals Collegiate: 8:05.4h C 5/13/1978 Henry Rono Finals Name Yr School Finals 1 Ersula Farrow SR LSU 4:22.91 48.268 (48.268) 1:59.079 (1:10.811) 3:11.164 (1:12.085) Finals 1 Elliott Miller SO Alabama 9:41.28 4:22.906 -

2017 Annual Meeting Committee Reports

2017 USATF ANNUAL MEETING COMMITTEE REPORTS 2017 Athletes Advisory Committee Annual Report Submitted October 30, 2017 Purpose: The purpose of this report is to summarize the strategic goals and progress towards such of the USATF Athletes Advisory Committee in 2017. Strategic Goal #1: Athlete Funding & Support Increase athlete funding through prize money, stipends, Revenue Distribution Plan The RDP contract is being finalized between the national office and the AAC to ensure fair treatment and no room for interpretation. A plan for the 2018 RDP money (since there is no team to make and be paid for) is being presented to the national office. Athletes need to be paid on time, in a predictable manner. A schedule is being put together detailing when each type of payment can be expected (Tier payments, prize money, RDP), to which the national office will be held accountable. The Emergency Relief Fund was finalized in 2016 to provide emergency financial assistance to current or recently retired athletes facing a catastrophic event causing financial distress. In 2017, the fund was first used to help athletes in dire situations. USATF has funded the account initially, with the AAC being responsible for future fundraising. Strategic Goal #2: Domestic Competitive Opportunities It is important to the AAC that we continue to seek out opportunities for domestic competitions to reduce the dependency on the European circuit. 2019 will be an especially important year, as the World Championships will take place much later than usual (late Sept/early Oct). We will need domestic competitive opportunities in June, July and August of 2019. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Adkins Trak Timing - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 6:27 PM 1/18/2019 Page 1 2019 Clemson Invitational - 1/18/2019 to 1/19/2019 Clemson University Indoor Complex Results - Friday - Field Events Women Pole Vault ================================================================================= American: A 5.03m 1/30/2016 Jenn Suhr, Adidas NCAA: N 4.75m 1/15/2015 Demi Payne, Stephen F. Austin Facility: F 4.46m 1/26/2018 Lisa Gunnarsson, Virginia Tec Name Year School Finals Points ================================================================================= Flight 1 1 Petty, Shay SR Texas 4.05m 13-03.50 3.30 3.45 3.60 3.75 3.90 4.05 PPP PPP PPP PPP O O 2 Dingler, Carson SO Georgia 3.75m 12-03.50 3.30 3.45 3.60 3.75 3.90 PPP PPP O O XXX 2 Buntin, Olivia FR Texas 3.75m 12-03.50 3.30 3.45 3.60 3.75 3.90 PPP PPP O O XXX 4 D'Alessandro, Alison SO Kentucky J3.75m 12-03.50 3.30 3.45 3.60 3.75 3.90 PPP PPP XXO XXO XXX 5 Caudill, Riley SO Kentucky 3.60m 11-09.75 3.30 3.45 3.60 3.75 PPP PPP O XXX 6 Bickett, Jaci FR Kentucky J3.60m 11-09.75 3.30 3.45 3.60 3.75 PPP PPP XO XXX 6 Long, Courtney FR Georgia J3.60m 11-09.75 3.30 3.45 3.60 3.75 PPP PPP XO XXX 8 Carroll, Alana FR Harvard J3.60m 11-09.75 3.30 3.45 3.60 3.75 PPP PPP XXO XXX 9 Bryan, Madison SR Ucf 3.30m 10-10.00 3.30 3.45 O XXX -- Goecki, Gabrielle FR Campbell NH 3.30 XXX -- Bagby, Nicole SO Kentucky NH 3.30 3.45 3.60 PPP PPP XXX Women Long Jump ================================================================================= American: A 7.23m 3/11/2012 Brittney Reese, Nike NCAA: -

Table of Contents

A Column By Len Johnson TABLE OF CONTENTS TOM KELLY................................................................................................5 A RELAY BIG SHOW ..................................................................................8 IS THIS THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES FINEST MOMENT? .................11 HALF A GLASS TO FILL ..........................................................................14 TOMMY A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS ........................................................17 NO LIGHTNING BOLT, JUST A WARM SURPRISE ................................. 20 A BEAUTIFUL SET OF NUMBERS ...........................................................23 CLASSIC DISTANCE CONTESTS FOR GLASGOW ...................................26 RISELEY FINALLY GETS HIS RECORD ...................................................29 TRIALS AND VERDICTS ..........................................................................32 KIRANI JAMES FIRST FOR GRENADA ....................................................35 DEEK STILL WEARS AN INDELIBLE STAMP ..........................................38 MICHAEL, ELOISE DO IT THEIR WAY .................................................... 40 20 SECONDS OF BOLT BEATS 20 MINUTES SUNSHINE ........................43 ROWE EQUAL TO DOUBELL, NOT DOUBELL’S EQUAL ..........................46 MOROCCO BOUND ..................................................................................49 ASBEL KIPROP ........................................................................................52 JENNY SIMPSON .....................................................................................55 -

Oly Roster CA-PA

2012 Team USA Olympic Roster (including Californians and Pacific Association/USATF athletes) (Compiled by Mark Winitz) Key Blue type indicates California residents, or athletes with strong California ties Green type indicates Californians who are Pacific Association/USATF members, or athletes with strong Pacific Association ties Bold type indicates past World Outdoor or Olympic individual medalist * Relay pools are composed of the 100m and 400m rosters, the athletes listed in each pool, plus any athlete already on the roster in any other event * All nominations are pending approval by the USOC board of directors. MEN 100m – Justin Gatlin (Orlando, Fla.), Tyson Gay (Clermont, Fla.), Ryan Bailey (Salem, Ore.) 200m – Wallace Spearmon (Dallas, Texas), Maurice Mitchell (Tallahassee, Fla.), Isiah Young (Lafayette, Miss.) 400m – LaShawn Merritt (Suffolk, Va.), Tony McQuay (Gainesville, Fla.), Bryshon Nellum (Los Angeles, Calif.) 800m – Nick Symmonds (Springfield, Ore.), Khadevis Robinson (Las Vegas, Nev.; former longtime Los Angeles-area resident), Duane Solomon (Los Angeles, Calif.) 1500 m– Leonel Manzano (Austin, Texas), Matthew Centrowitz (Eugene, Ore.), Andrew Whetting (Eugene, Ore.) 3000m Steeplechase – Evan Jager (Portland, Ore.), Donn Cabral (Conn.), Kyle Alcorn (Mesa, Ariz.; Buchanan H.S. /Clovis, Calif. '03) 5000m – Galen Rupp (Portland, Ore.), Bernard Lagat (Tucson, Ariz.), Lopez Lomong (Beaverton, Ore.) 10,000m – Galen Rupp (Portland, Ore.), Matt Tegenkamp (Portland, Ore.), Dathan Ritzenhein (Portland, Ore.) 20 km Race Walk – Trevor -

Jenny Simpson

T&FN INTERVIEW by Jon JennyJenny SimpsonSimpson Hendershott he last steeplechase Jenny Simpson ran—an Pre really was only my fifth 1500, TAmerican Record 9:12.50 for 5th in the ’09 then the sky’s the limit. World Championships—came some 18 months ago. T&FN: Does the level of competition Since then, the 24-year-old Colorado grad has matter? had mixed fortunes: her first pro year covered just Simpson: I think my own four outdoor races as a stress reaction at the head of racing in the past has shown that her right femur forced her to end her season early. really difficult and challenging But she has run well this winter. competitions bring out the best in Even though she has considered a future in me. I think I’ll be most challenged the 1500 (T&FN, March ’10), she asserts that she and closer in the 1500 and that’s “Something I definitely isn’t finished with her flagship event: exciting for me. And I think the 1500 and steeple is a good match not only feel I learned T&FN: Last year, we wrote about the prospects for this ability that I didn’t discover of U.S. women in the 1500. Are you still mainly I had until much later, but also for throughout a steeplechaser, my personality. Simpson In or are you T&FN: Have you learned from your college is that the weighing your Worlds and Olympic steeples not only A Nutshell prospects in that it’s more a middle-distance race but steeple is more •Personal: Jennifer Mae Bar- other distances also about your competitiveness? ringer was born August 23, and especially Simpson: I think so. -

[email protected]> Subject: RRW: Rupp Upset, Huddle Defends at USA Championships 10,000M Date: June 23, 2017 at 7:40:45 AM PDT To: [email protected]

From: Race Results Weekly <[email protected]> Subject: RRW: Rupp Upset, Huddle Defends At USA Championships 10,000m Date: June 23, 2017 at 7:40:45 AM PDT To: [email protected] RUPP UPSET, HUDDLE DEFENDS AT USA CHAMPIONSHIPS 10,000M By David Monti, @d9monti (c) 2017 Race Results Weekly, all rights reserved SACRAMENTO, Calif. (22-Jun) -- Galen Rupp's streak of eight consecutive USA 10,000m titles came to an end here tonight at Hornet Stadium when the two-time Olympic medalist faded in the final lap of choppy and slow race which was won by Oregon Track Club Elite's Hassan Mead in 29:01.44. Rupp, who runs for the Nike Oregon Project, finished fifth. On the women's side, Saucony's Molly Huddle extended her winning streak at these championships to three, comfortably winning the 25-lap race in a solid 31:19.86, the second- fastest by an American this year. MEN'S RACE BECAME CAT AND MOUSE AFFAIR While the women's contest was a traditional battle of endurance won off of a steady and strong pace, the men's race early on became a game of cat and mouse. Feeling no pressure to run a fast time, the men's pack jogged through the first 800 meters in 2:29, only slightly faster than the women (2:32). The group of 24 athletes was tightly bunched, with veteran Ben Bruce of Hoka Northern Arizona Elite at the front. With 19 laps to go, 2015 national road running champion Sam Chelanga became impatient. Coming down the homestretch, he shot to the lead and threw in a 64.7-second lap, followed by another at 65.1. -

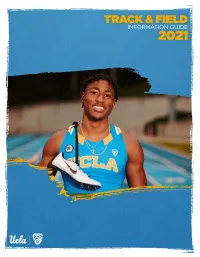

2020 21 Media Guide Comple

2021 UCLA TRACK & FIELD 2021 QUICK FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Location Los Angeles, CA The 2021 Bruins Men’s All-Time Indoor Top 10 65-66 Rosters 2-3 Athletic Dept. Address 325 Westwood Plaza Women’s All-Time Indoor Top 10 67-68 Coaching Staff 4-9 Los Angeles, CA 90095 Men’s All-Time Outdoor Top 10 69-71 Men’s Athlete Profles 10-26 Athletics Phone (310) 825-8699 Women’s All-Time Outdoor Top 10 72-74 Women’s Athlete Profles 27-51 Ticket Offce (310) UCLA-WIN Drake Stadium 75 Track & Field Offce Phone (310) 794-6443 History/Records Drake Stadium Records 76 Chancellor Dr. Gene Block UCLA-USC Dual Meet History 52 Bruins in the Olympics 77-78 Director of Athletics Martin Jarmond Pac-12 Conference History 53-55 USA Track & Field Hall of Fame Bruins 79-81 Associate Athletic Director Gavin Crew NCAA Championships All-Time Results 56 Sr. Women’s Administrator Dr. Christina Rivera NCAA Men’s Champions 57 Faculty Athletic Rep. Dr. Michael Teitell NCAA Women’s Champions 58 Home Track (Capacity) Drake Stadium (11,700) Men’s NCAA Championship History 59-61 Enrollment 44,742 Women’s NCAA Championship History 62-63 NCAA Indoor All-Americans 64 Founded 1919 Colors Blue and Gold Nickname Bruins Conference Pac-12 National Affliation NCAA Division I Director of Track & Field/XC Avery Anderson Record at UCLA (Years) Fourth Year Asst. Coach (Jumps, Hurdles, Pole Vault) Marshall Ackley Asst. Coach (Sprints, Relays) Curtis Allen Asst. Coach (Distance) Devin Elizondo Asst. Coach (Distance) Austin O’Neil Asst. -

To Download the 2015 IAAF Diamond League Media Guide (5.4Mb Pdf)

1 IAAF Diamond League 2015 media guide Contents 2......................... Introduction Diamond Race 3......................... Basic information – how it works, points, prize money 5......................... Diamond Race winners (2010-2014) 10....................... Diamond Race all-time statistics (2010-2014) 21....................... Competition review 2014 36....................... TV audiences 2015 season 37....................... Calendar 38....................... Event disciplines 40....................... Host broadcasters 41....................... Preview 42....................... Contact details – DL AG, IAAF, IMG, meeting organisers and press chiefs 48....................... Media accreditation 2 IAAF Diamond League 2015 media guide Introduction Welcome to the 2015 season of the IAAF Diamond League. During its first five seasons, the IAAF Diamond League has captured the public’s imagination like no other non-championship athletics competition. Spread across Asia, Europe, the Middle East and the USA, the 14-meeting series includes a competition programme of 32 events representing virtually the full spectrum of Olympic track and field disciplines, and offers a total of 8 million US dollars in prize money. At the core of the IAAF Diamond League is the Diamond Race with athletes battling season long to accumulate points in each of the 32 event disciplines to win a 40,000 USD cash prize, a spectacular Diamond Trophy and, having shown season-long consistency, the unchallenged honour of being their event’s world No.1. With the creation of the IAAF Diamond League in 2009, we set We look forward to working together in the next years to further out to reinvent the one-day meeting structure of our sport, to enhance the status, visibility and reach of athletics’ premier global bring clarity to the top tier of international invitational competition non-championship competition. -

Arguably the Most Accomplished Collegiate Runner the United Sates

6WURQJIURP +HDGWR)HHW Arguably the most accomplished collegiate runner the United Sates has ever seen, Jenny Barringer needed to connect her body and mind in order to reach her full potential. By Jayme Otto oeing the line for her !nal race as a college athlete, literal nightmare. She remembers feeling disconnected to re- Jenny Barringer’s head buzzed. The four-time ality and confused. Fans were equally stunned; Barringer had National Collegiate Athletic Association champ been perhaps the most consistent racer in NCAA history, had high hopes for the 2009 NCAA Cross Country setting collegiate records in indoor and outdoor track as well TChampionships. The stage was set for peak performance: the as cross country with seeming ease. Her performance in the autumn day was sunny, the 6k course wound through grass 2008 Olympics’ inaugural women’s 3,000-meter steeplechase, and dirt and Jenny had her hair secured in her trademark where she placed ninth and secured the American record in ponytail. But this time, her pre-race jitters were extreme. In the event, made Jenny appear unstoppable. addition to thinking win, her mind held a jumble of more What stunned Barringer and her fans alike was that there urgent thoughts: set an impossible pace to follow, annihilate the wasn’t an obvious explanation for what happened during the course record, dominate by 30 seconds—minimum. championship. She was healthy, free from injury, her train- At the gun, Barringer charged right to the front. She ing was on track and she’d been properly resting in the weeks ran in her typical con!dent style, but those who knew her leading up to the race. -

Women's 100M Final Women's 100M Semi-Finals

7/6/2021 2020 U.S. Olympic Team Trials - Track & Field COMPLETED EVENTS Compiled Results Women's 100m Final Results Top 3 in each heat and next 4 fastest advance to semis; Top 3 in each semi and next 2 fastest advance to nal Wind: -1.0 m/s 5 Gabby Thomas 11.15 6 PLACE ATHLETE RESULT LN/POS New Balance / Buford Bailey TC OLY STD 1 Sha'Carri Richardson 10.86 5 6 English Gardner 11.16 7 NIKE OLY STD NIKE OLY STD 2 Javianne Oliver 10.99 4 7 Aleia Hobbs 11.20 9 NIKE OLY STD adidas 3 Teahna Daniels 11.03 3 8 Kayla White 11.22 8 NIKE OLY STD NIKE OLY STD 4 Jenna Prandini 11.11 2 9 Candace Hill 11.23 1 PUMA OLY STD SB ASICS OLY STD Women's 100m Semi-Finals Results Top 3 in each heat and next 4 fastest advance to semis; Top 3 in each semi and next 2 fastest advance to nal PLACE ATHLETE RESULT REACT WIND HEA9T LN/POSDezerea Bryant 11.03 0.160 2.5 NIKE OLY STD m/s 1 Sha'Carri Richardson 10.64 Q 0.173 2.6 1 (1) 4 NIKE OLY STD m/s 10 Twanisha Terry 11.04 0.165 2.5 USC OLY STD m/s 2 Javianne Oliver 10.83 Q 0.162 2.5 2 (1) 5 NIKE OLY STD m/s 11 Mikiah Brisco 11.05 0.145 2.5 NIKE OLY STD 11.043 m/s 3 Teahna Daniels 10.84 Q 0.185 2.6 1 (2) 2 NIKE OLY STD m/s 12 Cambrea Sturgis 11.05 0.148 2.6 North Carolina A&T OLY STD 11.046 m/s 4 Gabby Thomas 10.95 Q 0.174 2.5 2 (2) 4 New Balance / Buford Bailey TC OLY STD m/s 13 Tianna Bartoletta 11.09 0.170 2.6 Unattached OLY STD m/s 5 English Gardner 10.96 Q 0.130 2.5 2 (3) 7 NIKE OLY STD 10.953 m/s 14 Morolake Akinosun 11.16 0.205 2.5 adidas OLY STD 11.157 m/s 6 Jenna Prandini 10.96 Q 0.151 2.6 1 (3) 6 PUMA 10.954 m/s 15 Maia McCoy 11.16 0.189 2.6 Tennessee OLY STD 11.158 m/s 7 Kayla White 10.98 q 0.145 2.6 1 (4) 3 NIKE OLY STD m/s FS Aleia Hobbs adidas OLY STD 8 Candace Hill 11.02 q 0.155 2.6 1 (5) 1 ASICS OLY STD m/s Heat-by-Heat 3 (6) Jenna Prandini 10.96 Q 6 Heat 1 PUMA Wind: 2.6 m/s 4 (7) Kayla White 10.98 q 3 PL ATHLETE MARK LN/POS NIKE 1 (1) Sha'Carri Richardson 4 10.64 Q 5 (8) Candace Hill 11.02 q 1 NIKE ASICS 2 (3) T h D i l 2 https://results.usatf.org/2020Trials/ 1/88 7/6/2021 2020 U.S. -

Fall 2012 Cover.Indd 1 10/15/12 3:08 PM FALL 2012 Contents VOLUME 19 • NUMBER 3

The Magazine of Rhodes College • Fall 2012 THE SCIENCES AT RHODES Past, Present and Future Fall 2012 cover.indd 1 10/15/12 3:08 PM FALL 2012 Contents VOLUME 19 • NUMBER 3 2 Campus News Briefs on campus happenings 5 The Sciences at Rhodes—Past, Present and Future Conversations with faculty, alumni and current students who majored in or are currently engaged in one of the six science disciplines Rhodes offers: 6 The Biochemists and Molecular Biologists Professor Terry Hill, Amanda Johnson Winters ’99, Ross 10 Hilliard ’07, Xiao Wang ’13 10 The Biologists Professor Gary Lindquester, Veronica Lawson Gunn ’91, Brian Wamhoff ’96, Anahita Rahimi-Saber ’13 14 The Chemists Professor Darlene Loprete, Sid Strickland ’68, Tony Capizzani ’95, Ashley Tufton ’13 18 The Environmental Scientists Professor Rosanna Cappellato, Cary Fowler ’71, Christopher Wilson ’95, Alix Matthews ’14 22 The Neuroscientists Professor Robert Strandburg, Jim Robertson ’53 and Jon Robertson ’68, Michael Long ’97, Piper Carroll ’13 14 26 The Physicists Professor Brent Hoffmeister, Harry Swinney ’61, Charles Robertson Jr. ’65, Lars Monia ’15 30 A Case for the Support of the Sciences at Rhodes The importance of strengthening the sciences in the 21st century 32 Alumni News Class Notes, In Memoriam The 2011-2012 Honor Roll of Donors On the Cover From left: Alix Matthews ’14, Ashley Tufton ’13, Piper Carroll ’13, Lars Monia ’15 and Xiao Wang ’13, fi ve of the six science majors featured in this issue, at the Lynx 26 sculpture in front of the Peyton Nalle Rhodes Tower, home of the Physics Department Photography by Justin Fox Burks Contents_Fall ’12.indd 1 10/15/12 3:05 PM is published three times a year by Rhodes College, 2000 N.