Adamawa) Emirate, 1809-1976

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESS RELEASE June 25, 2021 for Immediate Release U.S. Embassy

United States Diplomatic Mission to Nigeria, Public Affairs Section Plot 1075, Diplomatic Drive, Central Business District, Abuja Telephone: 09-461-4000. Website at http://nigeria.usembassy.gov PRESS RELEASE June 25, 2021 For Immediate Release U.S. Embassy Abuja Partners Channels Academy to Train Conflict Reporters The U.S. Embassy Abuja, in partnership with Channels Academy, has trained over 150 journalists on Conflict Reporting and Peace Journalism. In her opening remarks, the U.S. Embassy Spokesperson/Press Attaché Jeanne Clark noted that the United States recognized that security challenges exist in many forms throughout the country, and that journalists are confronted with responsibility to prioritize physical safety in addition to meeting standards of objectivity and integrity in conflict. She urged the journalists to share their experiences throughout the course of the three-day seminar and encouraged participants to identify new ways to address these security challenges. The trainer Professor Steven Youngblood from the U.S. Center for Global Peace Journalism – Park University defined and presented principles for peace journalism in conflict reporting. He cautioned journalists to refrain from what he termed war journalism. He said, "war journalism is a pattern of media coverage that includes overvaluing violent, reactive responses to conflict while undervaluing non-violent, developmental responses.” The Provost of Channels Academy, Mr Kingsley Uranta, showed appreciation for the continuous partnership with the U.S. Embassy and for bringing such training opportunities to Nigerian journalists. He also called on conflict reporters to be peace ambassadors. The training took place virtually via Zoom on June 22 – 24, 2021. Journalists converged in American Spaces in Abuja, Kano, Bauchi Sokoto, Maiduguri, Awka, and Ibadan. -

Nigeria: a New History of a Turbulent Century

More praise for Nigeria: A New History of a Turbulent Century ‘This book is a major achievement and I defy anyone who reads it not to learn from it and gain greater understanding of the nature and development of a major African nation.’ Lalage Bown, professor emeritus, Glasgow University ‘Richard Bourne’s meticulously researched book is a major addition to Nigerian history.’ Guy Arnold, author of Africa: A Modern History ‘This is a charming read that will educate the general reader, while allowing specialists additional insights to build upon. It deserves an audience far beyond the confines of Nigerian studies.’ Toyin Falola, African Studies Association and the University of Texas at Austin About the author Richard Bourne is senior research fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London and a trustee of the Ramphal Institute, London. He is a former journalist, active in Common wealth affairs since 1982 when he became deputy director of the Commonwealth Institute, Kensington, and was the first director of the non-governmental Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative. He has written and edited eleven books and numerous reports. As a journalist he was education correspondent of The Guardian, assistant editor of New Society, and deputy editor of the London Evening Standard. Also by Richard Bourne and available from Zed Books: Catastrophe: What Went Wrong in Zimbabwe? Lula of Brazil Nigeria A New History of a Turbulent Century Richard Bourne Zed Books LONDON Nigeria: A New History of a Turbulent Century was first published in 2015 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK www.zedbooks.co.uk Copyright © Richard Bourne 2015 The right of Richard Bourne to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 Typeset by seagulls.net Index: Terry Barringer Cover design: www.burgessandbeech.co.uk All rights reserved. -

States and Local Government Areas Creation As a Strategy of National Integration Or Disintegration in Nigeria

ISSN 2239-978X Journal of Educational and Social Research Vol. 3 (1) January 2013 States and Local Government Areas Creation as a Strategy of National Integration or Disintegration in Nigeria Bassey, Antigha Okon #!230#0Q#.02+#,2-$-!'-*-%7 !3*27-$-!'*!'#,, 4#01'27-$* 0 TTTWWV[* 0$TT– Nigeria E-mail: &X)Z&--T!-+, &,#SV^VYY[Z_YY\ Omono, Cletus Ekok #!230#0Q#.02+#,2-$-!'-*-%7 !3*27-$-!'*!'#,, 4#01'27-$* 0 Bisong, Patrick Owan #!230#0Q#.02+#,2-$-!'-*-%7 Facult$-!'*!'#,, 4#01'27-$* 0 Bassey, Umo Antigha !3*27-$1"3!2'-, ,'4#01'27-$* 0 Doi: 10.5901/jesr.2013.v3n1p237 Abstract 3&'1..#0#6+',#1122#1,"*-!*%-4#0,+#,20#1!0#2'-,',5'%#0'1-,#-$2&+(-01202#%'#1of #,130',%52'-,*',2#%02'-,T3&#,*71'15 1#"-,1#""2- 2',#"$0-+2#6 )1,"-2� 0#20'#4#" +2#0'*1T 3&# 1!-.# -$ 2&# ..#0 -� 2&, 2&# "!2'-,Q !-4#01R !-,!#.23* ,*71'1 -$ 40' *#1R 0#4'#5 -$ *-!* %-4#0,+#,2 0#as and states creation in Nigeria, rationale for States and Local 90,+#,21!0#R2&#-0#2'!*$"R!-,1#/#,!#1R!-,!*31'-,"0#!-++#,"-,T<2#0!0'2'!* #6+',2'-, -$ 2&# !-,1#/#,!#1 -$ !0#2'-, -$ 122#1 "*-!*%-4#0,+#,2 0#15hich include structural imbalance in Nigeria socio-1203!230#R.#0.#232'-,-$+',-0'27"-+',2'-,Q!-,2',3-311203%%*#$-0 national resources in terms of sharing national revenue and creation of consciousness among ethnic nationalities. State and Local government creation rather promotes National disintegration. The conclusion of &'1 ..#0 2�#$-0# "#4'2#1 1'%,'$'!,2*7 $0-+ 2&# ',2#,"" $3,!2'-, -$ 122# !0#2'-, 1 #6!2#" 7 2&# %'22-01T3&'1..#0381$3,!2'-,*&',,*8g state and local government creation in Nigeria "'2'10#!-++#""2&2&##"0*9-4#0,+#,21&-3*"',20-"3!#"-+'!'*'07.-*'!72-1-*4#2&#.0- *#+ of non-indigenes and minorities. -

Aquifers in the Sokoto Basin, Northwestern Nigeria, with a Description of the Genercl Hydrogeology of the Region

Aquifers in the Sokoto Basin, Northwestern Nigeria, With a Description of the Genercl Hydrogeology of the Region By HENRY R. ANDERSON and WILLIAM OGILBEE CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF AFRICA AND THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1757-L UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1973 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 73-600131 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Pri'ntinll Office Washinl\ton, D.C. 20402 - Price $6.75 Stock Number 2401-02389 CONTENTS Page Abstract -------------------------------------------------------- Ll Introduction -------------------------------------------------·--- 3 Purpose and scope of project ---------------------------------- 3 Location and extent of area ----------------------------------- 5 Previous investigations --------------------------------------- 5 Acknowledgments -------------------------------------------- 7 Geographic, climatic, and cultural features ------------------------ 8 Hydrology ----------------------_---------------------- __________ 10 Hydrogeology ---------------------------------------------------- 17 General features -------------------------------------------- 17 Physical character of rocks and occurrence of ground water ------- 18 Crystalline rocks (pre-Cretaceous) ------------------------ 18 Gundumi Formation (Lower Cretaceous) ------------------- 19 Illo Group (Cretaceous) ---------------------------------- -

Surviving Works: Context in Verre Arts Part One, Chapter One: the Verre

Surviving Works: context in Verre arts Part One, Chapter One: The Verre Tim Chappel, Richard Fardon and Klaus Piepel Special Issue Vestiges: Traces of Record Vol 7 (1) (2021) ISSN: 2058-1963 http://www.vestiges-journal.info Preface and Acknowledgements (HTML | PDF) PART ONE CONTEXT Chapter 1 The Verre (HTML | PDF) Chapter 2 Documenting the early colonial assemblage – 1900s to 1910s (HTML | PDF) Chapter 3 Documenting the early post-colonial assemblage – 1960s to 1970s (HTML | PDF) Interleaf ‘Brass Work of Adamawa’: a display cabinet in the Jos Museum – 1967 (HTML | PDF) PART TWO ARTS Chapter 4 Brass skeuomorphs: thinking about originals and copies (HTML | PDF) Chapter 5 Towards a catalogue raisonnée 5.1 Percussion (HTML | PDF) 5.2 Personal Ornaments (HTML | PDF) 5.3 Initiation helmets and crooks (HTML | PDF) 5.4 Hoes and daggers (HTML | PDF) 5.5 Prestige skeuomorphs (HTML | PDF) 5.6 Anthropomorphic figures (HTML | PDF) Chapter 6 Conclusion: late works ̶ Verre brasscasting in context (HTML | PDF) APPENDICES Appendix 1 The Verre collection in the Jos and Lagos Museums in Nigeria (HTML | PDF) Appendix 2 Chappel’s Verre vendors (HTML | PDF) Appendix 3 A glossary of Verre terms for objects, their uses and descriptions (HTML | PDF) Appendix 4 Leo Frobenius’s unpublished Verre ethnological notes and part inventory (HTML | PDF) Bibliography (HTML | PDF) This work is copyright to the authors released under a Creative Commons attribution license. PART ONE CONTEXT Chapter 1 The Verre Predominantly living in the Benue Valley of eastern middle-belt Nigeria, the Verre are one of that populous country’s numerous micro-minorities. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: an Historical Analysis, 1804-1960

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: An Historical Analysis, 1804-1960 by Kari Bergstrom Michigan State University Winner of the Rita S. Gallin Award for the Best Graduate Student Paper in Women and International Development Working Paper #276 October 2002 Abstract This paper looks at the effects of Islamization and colonialism on women in Hausaland. Beginning with the jihad and subsequent Islamic government of ‘dan Fodio, I examine the changes impacting Hausa women in and outside of the Caliphate he established. Women inside of the Caliphate were increasingly pushed out of public life and relegated to the domestic space. Islamic law was widely established, and large-scale slave production became key to the economy of the Caliphate. In contrast, Hausa women outside of the Caliphate were better able to maintain historical positions of authority in political and religious realms. As the French and British colonized Hausaland, the partition they made corresponded roughly with those Hausas inside and outside of the Caliphate. The British colonized the Caliphate through a system of indirect rule, which reinforced many of the Caliphate’s ways of governance. The British did, however, abolish slavery and impose a new legal system, both of which had significant effects on Hausa women in Nigeria. The French colonized the northern Hausa kingdoms, which had resisted the Caliphate’s rule. Through patriarchal French colonial policies, Hausa women in Niger found they could no longer exercise the political and religious authority that they historically had held. The literature on Hausa women in Niger is considerably less well developed than it is for Hausa women in Nigeria. -

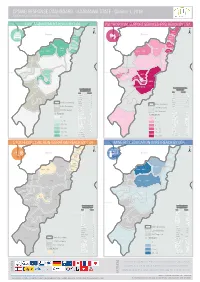

CPSWG RESPONSE DASHBOARD - ADAMAWA STATE - Quarter 1, 2019 Child Protection Sub Working Group, Nigeria

CPSWG RESPONSE DASHBOARD - ADAMAWA STATE - Quarter 1, 2019 Child Protection Sub Working Group, Nigeria YobeCASE MANAGEMENT REACH BY LGA PSYCHOSOCIALYobe SUPPORT SERVICES (PSS) REACH BY LGA 78% 14% Madagali ± Madagali ± Borno Borno Michika Michika 86% 10% 82% 16% Mubi North Mubi North Hong 100% Mubi South 5% Hong Gombi 100% 100% Gombi 10% 27% Mubi South Shelleng Shelleng Guyuk Song 0% Guyuk Song 0% 0% Maiha 0% Maiha Chad Chad Lamurde 0% Lamurde 0% Nigeria Girei Nigeria Girei 36% 81% 11% 96% Numan 0% Numan 0% Yola North Demsa 100% Demsa 26% Yola North 100% 0% Adamawa Fufore Yola South 0% Yola South 100% Fufore Mayo-Belwa Mayo-Belwa Adamawa Local Government Area Local Government (LGA) Target Area (LGA) Target LGA TARGET LGA TARGET Demsa 1,170 DEMSA 78 Fufore 370 Jada FUFORE 41 Jada Ganye 0 GANYE 0 Girei 933 GIREI 16 Gombi 4,085 State Boundary GOMBI 33 State Boundary Guyuk 0 GUYUK 0 LGA Boundary Hong 16,941 HONG 6 Ganye Ganye LGA Boundary Jada 0 JADA 0 Not Targeted Lamurde 839 LAMURDE 6 Not Targeted Madagali 6,321 MADAGALI 119 % Reach Maiha 2,800 MAIHA 12 % REACH Mayo-Belwa 0 0 MAYO - BELWA 0 0 Michika 27,946 Toungo 0% MICHIKA 232 Toungo 0% 1 - 36 Mubi North 11,576 MUBI NORTH 154 1 - 5 Mubi South 11,821 MUBI SOUTH 139 37 - 78 Numan 2,250 NUMAN 14 6 - 11 Shelleng 0 SHELLENG 0 79 - 82 12 - 16 Song 1,437 SONG 21 Teungo 25 83 - 86 TOUNGO 6 17 - 27 Yola North 1,189 YOLA NORTH 14 Yola South 2,824 87 - 100 YOLA SOUTH 47 28 - 100 SOCIO-ECONOMICYobe REINTEGRATION REACH BY LGA MINEYobe RISK EDUCATION (MRE) REACH BY LGA Madagali Madagali R 0% I 0% ± -

Comparative Economics of Fresh and Smoked Fish Marketing in Some Local Government Areas in Adamawa State, Nigeria

COMPARATIVE ECONOMICS OF FRESH AND SMOKED FISH MARKETING IN SOME LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREAS IN ADAMAWA STATE, NIGERIA. ONYIA, L.U., ADEBAYO, E.F., ADEWUYI, K.O., EKWUNIFE, E.G., OCHOKWU,I.J, OUTLINE OF PRESENTATION • INTRODUCTION • MATERIALS AND METHODS • RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS • CONCLUSIONS • RECOMMENDATIONS INTRODUCTION ü FISH IS A MAJOR SOURCE OF ANIMAL PROTEIN, ü ESSENTIAL FOOD ITEM IN THE DIET OF NIGERIANS (JIM-SAIKI AND OGUNBADEJO, 2003), ü AN IMPORTANT SOURCE OF LIFE AND LIVELIHOODS FOR MILLIONS OF PEOPLE AROUND THE WORLD AND FOR THAT MATTER THE SELECTED COMMUNITIES, ü PROVIDES A SPENDABLE INCOME FOR MANY FAMILIES IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD (JERE AND MWENDO-PEHIRI, 2004). INTRODUCTION CONTINUED v IN NIGERIA, FISH IS SOLD TO CONSUMERS AS: ü FROZEN OR ICED, ü CURED (SMOKED), ü SUN DRIED, ü FRESH EITHER FROM A CULTURED POND OR FROM THE WILD. OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY • TO IDENTIFY SOCIOECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS OF THE FISH MARKETERS • TO COMPARE ECONOMIC BENEFITS OF FRESH AND SMOKED FISH ENTERPRISES IN THE STUDY AREAS. MATERIALS AND METHODS THE STUDY AREA ü SEVEN LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREAS OF ADAMAWA STATE (NGURORE, YOLA SOUTH, YOLA NORTH, GIREI, DEMSA, FUFORE AND NUMAN) WERE RANDOMLY SELECTED BASED ON THEIR PROXIMITY TO THE FISH LANDING SITES, ü DATA COLLECTED THROUGH WELL-STRUCTURED QUESTIONNAIRE OF FRESH AND SMOKED FISH MARKETERS FROM 7 MARKETS, ü 286 QUESTIONNAIRES WERE RANDOMLY DISTRIBUTED AMONG THE FISH MARKETERS. METHOD OF DATA ANALYSIS • DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS IN TERMS OF FREQUENCIES AND PERCENTAGES • GROSS MARGIN ANALYSIS WAS USED TO DETERMINE -

LGA Demsa Fufore Ganye Girei Gombi Guyukk Hong Jada Lamurde

LGA Demsa Fufore Ganye Girei Gombi Guyukk Hong Jada Lamurde Madagali Maiha Mayo Belwa Michika Mubi North Mubi South Numan Toungo Shellenge Song Yola North Yola South PVC PICKUP ADDRESS Along Gombe Road, Demsa Town, Demsa Local Govt. Area Gurin Road, Adjacent Local Govt. Guest House, Fufore Local Govt. Area Along Federal Government College, Ganye Road, Ganye Lga Adjacent Local Govt. Guest Road, Girei Local Govt. Area Sangere Gombi, Aong Yola Road, Gombi L.G.A Palamale Nepa Ward Guyuk Town, Guyuk Local Govt. Area Opposite Cottage Hospital Shangui Ward, Hong Local Govt. Area Old Secretariat, Jada Along Ganye Road, Jada Lafiya Lamurde Road, Lamurde Local Govt. Area Palace Road, Gulak, Near Gulak Police Station, Madagali Lga Behind Local Govt. Secretariat, Mayonguli Ward, Maiha Jalingo Road Near Maternity Mayo Belwa Lga Michika Bye-Pass Zaibadari Ward Michika Lga Inside Local Govt. Secretariat, Mubi North Lumore Street, Opposite District Head's Palace, Gela, Mubi South Councilors Quarters, Off Jalingo Road, Numan Lga Barade Road, Oppoiste Sss Office, Toungo Old Local Govt Secretariat Street, Shelleng Town, Shelleng Lga Opp. Cattage Hospital Yola Road, Song Local Govt. Area No. 7 Demsawo Street, Demsawo Ward, Yola North Lga Yola Bye-Pass Fufore Road Opp. Aliyu Mustapha College, Bako Ward, Yola Town, Yola South Lga Yola Bye-Pass Fufore Road Opp. Aliyu Mustapha College, Bako Ward, Yola Town, Yola South Lga. -

Sokoto Journal of Veterinary Sciences Oestrus Synchronisation in Red

Sokoto Journal of Veterinary Sciences, Volume 17 (Number 2). June, 2019 SHORT COMMUNICATION Sokoto Journal of Veterinary Sciences (P-ISSN 1595-093X: E-ISSN 2315-6201) http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/sokjvs.v17i2.9 Bello et al./Sokoto Journal of Veterinary Sciences, 17(2): 65 - 68. Oestrus synchronisation in Red Sokoto does treated with prostaglandin F2α and progesterone pessaries AA Bello1*, AA Voh Jr2, D Ogwu1 & LB Tekdek3 1. Department of Theriogenology and Production, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, Nigeria 2. National Animal Production Research Institute, Shika, Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, Nigeria 3. Department of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, Nigeria *Correspondence: Tel.: +234803615348 3; E-mail: [email protected] Copyright: © 2019 Abstract Bello et al. This is an Comparative oestrus synchronisation was carried out in 52 Red Sokoto does with the open-access article aim of evaluating the effectiveness and tightness of synchrony of prostaglandin F2- published under the alpha (PGF2α) and progesterone pessaries for clinical application. Does were randomly terms of the Creative divided into PGF2α treated (n = 18), progesterone pessaries treated (n = 18) and Commons Attribution control (n = 16) groups. A double injection protocol of PGF2α, 12-days apart, and License which permits progesterone pessaries inserted for 12-days were used to synchronise oestrus, with unrestricted use, no treatment to the Control group. Six sexually active bucks were used as heat distribution, and detectors. Intensive and non-intensive oestrus detections were employed using visual reproduction in any observation and apronisation. Standing to be mounted was used as the main sign of medium, provided the oestrus. -

Adamawa - Health Sector Reporting Partners (April - June, 2020)

Nigeria: Adamawa - Health Sector Reporting Partners (April - June, 2020) Number of Local Reporting PARTNERS PER TYPE Government Area Partners OF ORGANIZATIONS BREAKDOWN OF PEOPLE REACHED PER CATEGORY NGOs/UN People Reached PiN/Target IDP Returnee Host Agencies Community 21 Partners14 including 230,996 LGAs with ongoing International NGOs and activities 95,764 13,922 1,268 80,573 UN Agencies 11/3 212,433 DEMSA (4 Partners) MICHIKA (6 Partners) FSACI, IOM, JHF, WHO GZDI, IRC, JHF, PLAN, WHO, ZSF MADAGALI REACHED: 6,070 REACHED: 6,578 FUFORE (4 Partners) MUBI NORTH (7 Partners) MICHIKA GDZI, IOM, JHF, LESGO, PLAN, IOM, JHF, UNICEF, WHO SWOGE, WHO REACHED: 17,309 REACHED: 6,924 MUBI NORTH GANYE (2 Partners) MUBI SOUTH (6 Partners) HONG JHF GDZI, IOM, JHF, LESGO, RHHF, ZSF GOMBI MUBI SOUTH REACHED: - REACHED: 4,090 GIREI (4 Partners) NUMAN (1 Partner) SHELLENG JHF AGUF, IOM, JHF, WHO MAIHA REACHED: 22,348 REACHED: - SONG GUYUK GOMBI (3 Partners) SHELLENG (1 Partner) JHF GDZI, JHF, WHO LAMURDE REACHED: 220 REACHED: - GIREI GUYUK (2 Partners) SONG (2 Partners) NUMAN AGUF, JHF JHF DEMSA REACHED: - REACHED: 7,355 YOLA SOUTH YOLA NORTH HONG (3 Partners) TOUNGO (1 Partner) GDZI, JHF, WHO JHF MAYO FUFORE REACHED: 423 REACHED: - BELWA JADA (1 Partner) YOLA NORTH (4 Partners) HARAF, IOM, JHF, UNICEF JHF JADA REACHED: - REACHED: 1,224 LAMURDE (1 Partner) YOLA SOUTH (4 Partners) GANYE JHF IOM, JHF, SWOGE, UNICEF Number of Organizations REACHED: - REACHED: 7,355 (3 Partners) MADAGALI 1 7 JHF, PLAN, WHO TOUNGO REACHED: 4,537 MAIHA (2 Partners) JHF, WHO