A Bibliography of the Richard Johnson Collection of Hardyana “Hardy’S Se�Ings Always Intrigued Me” “HARDY’S SETTINGS ALWAYS INTRIGUED ME”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poems by Thomas Hardy Questions by Dr

Poems by Thomas Hardy Questions by Dr. Boos “Channel Firing” 1. Why does Hardy set this poem in a churchyard? What is the point of using such expressions as “the glebe cow” and “Christes sake”? 2. From whose point of view is the poem told? What is the effect of making “God” a character in the poem? 3. What is the effect of the stanza form and rhythm? 4. What do you make of God’s use of colloquial expression? 5. What dead human being receives the last word, and why is he chosen? 6. Are there droll or humorous aspects to the poem? Even if so, is the poem ultimately lighthearted? 7. What is the meaning of the poem? What is added by the final allusions to “Stourton Tower, / And Camelot, and starlit Stonehenge”? “The Oxen” 1. To what legend does the poem refer? Why do you think Hardy chose the legend of the kneeling oxen to represent Chrismas rather than, say, legends of angels or Santa Claus? 2. What are features of the poem’s stanza form, rhythms, and rhymes? Are they appropriate for the topic? Is the poem too short? 3. How is dialogue and direct address used in the poem? What effect do these have? 4. What characterizes Hardy’s word choice? Would his audience have used words such as “barton” and “coomb”? 5. What does Hardy think of the truth of this legend? Why does he say that “I feel” I would go with a messenger reporting this event? 6. What are some implications of the finallLine? Are there beliefs beyond the legend of kneeling oxen in which the poet can have no faith? Or is the final line indeterminate? 7. -

Music Inspired by the Works of Thomas Hardy

This article was first published in The Hardy Review , Volume XVI-i, Spring 2014, pp. 29-45, and is reproduced by kind permission of The Thomas Hardy Association, editor Rosemarie Morgan. Should you wish to purchase a copy of the paper please go to: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/ttha/thr/2014/00000016/0 0000001/art00004 LITERATURE INTO MUSIC: MUSIC INSPIRED BY THE WORKS OF THOMAS HARDY Part Two: Music composed after Hardy’s lifetime CHARLES P. C. PETTIT Part One of this article was published in the Autumn 2013 issue. It covered music composed during Hardy’s lifetime. This second article covers music composed since Hardy’s death, coming right up to the present day. The focus is again on music by those composers who wrote operatic and orchestral works, and only mentions song settings of poems, and music in dramatisations for radio and other media, when they were written by featured composers. Hardy’s work is seen to have inspired a wide variety of music, from full-length operas and musicals, via short pieces featuring particular fictional episodes, to ballet music and purely orchestral responses. Hardy-inspired compositions show no sign of reducing in number over the decades. However despite the quantity of music produced and the quality of much of it, there is not the sense in this period that Hardy maintained the kind of universal appeal for composers that was evident during the last two decades of his life. Keywords : Thomas Hardy, Music, Opera, Far from the Madding Crowd , Tess of the d’Urbervilles , Alun Hoddinott, Benjamin Britten, Elizabeth Maconchy In my earlier article, published in the Autumn 2013 issue of the Hardy Review , I covered Hardy-inspired music composed during Hardy’s lifetime. -

Thomas Hardy Poems

1 Thomas Hardy Poems Thomas Hardy (1840 1928) was an English novelist and poet. After a successful writing career that included such novels as Far from the Madding Crowd (1874), The Return of the Native (1878), The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886), and Tess of the D’Urbervilles (1891), his last novel, Jude the Obscure (1895) was roundly condemned by the church as immoral. After that, Hardy concentrated on writing poetry. In 1898 he published Wessex Poems; he continued to publish poetry throughout the rest of his life. “The Man He Killed” (1909) Had he and I but met By some old ancient inn, We should have set us down to wet Right many a nipperkin! But ranged as infantry, 5 And staring face to face, I shot at him as he at me, And killed him in his place. I shot him dead because— Because he was my foe, 10 Just so: my foe of course he was; That's clear enough; although He thought he'd 'list, perhaps, Off-hand like—just as I— Was out of work—had sold his traps— 15 No other reason why. Yes; quaint and curious war is! You shoot a fellow down You'd treat, if met where any bar is, Or help to half a crown. 20 Neutral Tones (1898) We stood by a pond that winter day, And the sun was white, as though chidden of God, And a few leaves lay on the starving sod; —They had fallen from an ash, and were gray. Your eyes on me were as eyes that rove 5 2 Over tedious riddles solved years ago; And some words played between us to and fro On which lost the more by our love. -

A Commentary on the Poems of THOMAS HARDY

A Commentary on the Poems of THOMAS HARDY By the same author THE MAYOR OF CASTERBRIDGE (Macmillan Critical Commentaries) A HARDY COMPANION ONE RARE FAIR WOMAN Thomas Hardy's Letters to Florence Henniker, 1893-1922 (edited, with Evelyn Hardy) A JANE AUSTEN COMPANION A BRONTE COMPANION THOMAS HARDY AND THE MODERN WORLD (edited,for the Thomas Hardy Society) A Commentary on the Poems of THOMAS HARDY F. B. Pinion ISBN 978-1-349-02511-4 ISBN 978-1-349-02509-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-02509-1 © F. B. Pinion 1976 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 15t edition 1976 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission First published 1976 by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London and Basingstoke Associated companies in New York Dublin Melbourne Johannesburg and Madras SBN 333 17918 8 This book is sold subject to the standard conditions of the Net Book Agreement Quid quod idem in poesi quoque eo evaslt ut hoc solo scribendi genere ..• immortalem famam assequi possit? From A. D. Godley's public oration at Oxford in I920 when the degree of Doctor of Letters was conferred on Thomas Hardy: 'Why now, is not the excellence of his poems such that, by this type of writing alone, he can achieve immortal fame ...? (The Life of Thomas Hardy, 397-8) 'The Temporary the AU' (Hardy's design for the sundial at Max Gate) Contents List of Drawings and Maps IX List of Plates X Preface xi Reference Abbreviations xiv Chronology xvi COMMENTS AND NOTES I Wessex Poems (1898) 3 2 Poems of the Past and the Present (1901) 29 War Poems 30 Poems of Pilgrimage 34 Miscellaneous Poems 38 Imitations, etc. -

English Compulsory – Ii

ENGLISH COMPULSORY – II B.A. English Semester - I BAG - 103 SHRI VENKATESHWARA UNIVERSITY UTTAR PRADESH-244236 BOARD OF STUDIES Prof (Dr.) P.K.Bharti Vice Chancellor Dr. Rajesh Singh Director Directorate of Distance Education SUBJECT EXPERT Dr. S.K.Bhogal, Professor Dr. Yogeshwar Prasad Sharma, Professor Dr. Uma Mishra, Asst. Professor COURSE CO-ORDINATOR Mr. Shakeel Kausar Dy. Registrar Authors Dr Priyanka Bhardwaj, Units: (1, 2.0-2.2, 2.2.1, 2.4.3, 2.5.1, 2.6.3, 2.9.2, 2.10-2.14) © Dr Priyanka Bhardwaj, 2019 Dr Shuchi Agrawal, Units: (2.3, 2.4-2.4.2, 2.9-2.9.1, 3.2.3) © Dr Shuchi Agrawal, 2019 Khusi Pattanayak, Units: (2.3.1-2.3.4, 2.6.2, 2.8-2.8.1) © Khusi Pattanayak, 2019 Deb Dulal Halder, Units: (2.5, 2.6-2.6.1, 2.7-2.7.1) © Deb Dulal Halder, 2019 Vivek Kumar, Units: (3.0-3.1, 3.2-3.2.2, 3.2.4-3.2.5, 3.3-3.4.3, 3.5-3.5.3, 3.6-3.10) © Vivek Kumar, 2019 Dr Joita Dhar Rakshit, Unit: (4.2-4.4) © Dr Joita Dhar Rakshit, 2019 Pramindha Banerjee, Unit: (5.3, 5.4.3) © Pramindha Banerjee, 2019 Vikas Publishing House, Units: (4.0-4.1, 4.5-4.9, 5.0-5.2, 5.4-5.4.2, 5.5-5.9) © Reserved, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. -

Neutral Tones

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com Neutral Tones day—the other person's face, the sun, the pond, the trees, and POEM TEXT the fallen leaves. 1 We stood by a pond that winter day, THEMES 2 And the sun was white, as though chidden of God, 3 And a few leaves lay on the starving sod; 4 – They had fallen from an ash, and were gray. LOVE AND LOSS “Neutral Tones” is a melancholic poem that looks at 5 Your eyes on me were as eyes that rove the dying moments of a relationship between the 6 Over tedious riddles of years ago; speaker and his (or her) lover. Defeated in tone, the poem 7 And some words played between us to and fro shows the way in which love contains the possibility of loss. It also demonstrates how this loss can completely alter a person’s 8 On which lost the more by our love. perception of the world and the person they once loved. Through the example of the speaker and the speaker's lover, 9 The smile on your mouth was the deadest thing the poem shows how embracing love always involves risking 10 Alive enough to have strength to die; painful loss and estrangement, and it even suggests that all love 11 And a grin of bitterness swept thereby might inherently deceptive. 12 Like an ominous bird a-wing…. The speaker captures a very specific moment in the poem: the death of the love between two people. Though the reader 13 Since then, keen lessons that love deceives, doesn’t know anything about the history of the relationship 14 And wrings with wrong, have shaped to me (including the gender of the speaker or the lover), the speaker 15 Your face, and the God curst sun, and a tree, creates a vivid, detailed depiction of exactly what the couple’s 16 And a pond edged with grayish leaves. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Miroslav Kohut Gender Relations in the Narrative Organization of Four Short Stories by Thomas Hardy Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. 2011 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature 2 I would like to thank Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. for his valuable advice during writing of this thesis. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Thomas Hardy as an author ..................................................................................... 7 1.2 The clash of two worlds in Hardy‘s fiction ............................................................. 9 1.3 Thomas Hardy and the issues of gender ............................................................... 11 1.4 Hardy‘s short stories ............................................................................................. 14 2. The Distracted Preacher .............................................................................................. 16 3. An Imaginative Woman .............................................................................................. 25 4. The Waiting Supper .................................................................................................... 32 5. A Mere Interlude -

Desire and the “Expressive Eye” Introduction : Le Désir Et L’Expression Du Regard

FATHOM a French e-journal of Thomas Hardy studies 5 | 2018 Desire and the Expressive Eye Introduction: Desire and the “Expressive Eye” Introduction : le désir et l’expression du regard Annie Ramel Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/fathom/854 DOI: 10.4000/fathom.854 ISSN: 2270-6798 Publisher Association française sur les études sur Thomas Hardy Electronic reference Annie Ramel, « Introduction: Desire and the “Expressive Eye” », FATHOM [Online], 5 | 2018, Online since 22 April 2018, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/fathom/854 ; DOI : 10.4000/fathom.854 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. Introduction: Desire and the “Expressive Eye” 1 Introduction: Desire and the “Expressive Eye” Introduction : le désir et l’expression du regard Annie Ramel EDITOR'S NOTE Several articles from this issue are being published jointly by FATHOM and the Hardy Review as part of a collaborative work. “In a Eweleaze Near Weatherbury” (Illustrations 154) 1 Hardy’s famous drawing of a pair of glasses superimposed on a pastoral landscape, an illustration for the poem “In a Eweleaze near Weatherbury”, is chosen by Catherine Lanone as her starting-point in the essay she wrote for this volume. What better illustration could be found for our subject, whose problematics is the connection between desire and the gaze? Indeed the onlooker requires glasses to see the landscape better: are we not all afflicted by some kind of structural myopia, or “misvision”? Does not the Bible repeatedly assert that we have eyes, but cannot see? (see Jeremiah 5:21, Ezekiel 12:2, FATHOM, 5 | 2018 Introduction: Desire and the “Expressive Eye” 2 Mark 4:12 and 8:18). -

?. M Ot, Minor Professor

THOMAS HARDY AND ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER: A COMPARATIVE STUDY APPROVED: Major Professor /?. M Ot, Minor Professor f-s>- eut~ Director of the Department of English. Dean of the Graduate School ' THOMAS HARDY AND ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER: A COMPARATIVE STUDY THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Jerry Keys Denton, Texas June, 1969 TABLE OP CONTENTS Chapter Pag© I. INTRODUCTION 1 II, THE PHILOSOPHY OP SCHOPENHAUER ....... $ III. HARDY AND SCHOPENHAUER 31 IV. TESS OF TEE D1URBERVILLES AND JUDE THE OBSCURE: AN EXPRESSION OP SCHOPENHAUER«S PHILOSOPHY $2 V. THOMAS HARDY1S POETRY: AN EXPRESSION OP PHILOSOPHICAL DEVELOPMENT 73 VI. CONCLUSION . 96 BIBLIOGRAPHY 101 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The purpose of this thesis is to show the influence of Arthur Schopenhauer's philosophy upon two of Thomas Hardy's novels and selected poems from six volumes of his poetry* Both writers saw the first cause of our universe as a blind, unconscious force, and this study will concern itself with how closely Thomas Hardy's philosophy resembles that of Schopenhauer and how Schopenhauer's concepts affected Hardy's writing# Hardy a product of the. philosophic and scientific rebellion of the nineteenth century. His aesthetic response to this realistic view of nature and the universe wa-s sensitive and intellectual. Hardy af*©iee contemptuously of "Nature's holy plan" and stressed a view of reality in which the first cause of the universe wa*s unconscious of man's suffering and desires# The unconscious quality of the first cause is the essence of Schopenhauer's concept of a blind, striving will to live. -

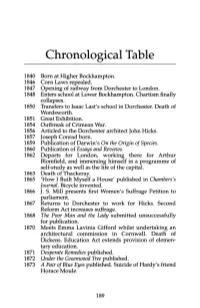

Chronological Table

Chronological Table 1840 Born at Higher Bockhampton. 1846 Corn Laws repealed. 1847 Opening of railway from Dorchester to London. 1848 Enters school at Lower Bockhampton. Chartism finally collapses. 1850 Transfers to Isaac Last's school in Dorchester. Death of Wordsworth. 1851 Great Exhibition. 1854 Outbreak of Crimean War. 1856 Articled to the Dorchester architect John Hicks. 1857 Joseph Conrad born. 1859 Publication of Darwin's On the Origin of Species. 1860 Publication of Essays and Reviews. 1862 Departs for London, working there for Arthur Blomfield, and immersing himself in a programme of self-study as well as the life of the capital. 1863 Death of Thackeray. 1865 'How I Built Myself a House' published in Chambers's Journal. Bicycle invented. 1866 J. S. Mill presents first Women's Suffrage Petition to parliament. 1867 Returns to Dorchester to work for Hicks. Second Reform Act increases suffrage. 1868 The Poor Man and the Lady submitted unsuccessfully for publication. 1870 Meets Emma Lavinia Gifford whilst undertaking an architectural commission in Cornwall. Death of Dickens. Education Act extends provision of elemen tary education. 1871 Desperate Remedies published. 1872 Under the Greenwood Tree published. 1873 A Pair of Blue Eyes published. Suicide of Hardy's friend Horace Moule. 189 190 Chronological Table 1874 Publication of Far from the Madding Crowd allows Hardy the financial stability to marry Emma Lavinia Gifford. 1876 Publication of The Hand of Ethelberta. Acquire for the first time a house to themselves, at Sturminster Newton. The Return of the Native written here, and the marriage enters its happiest period. Invention of tele phone and phonograph. -

THOMAS HARDY the V Ariorun1 Edition OF

THE VARIORUM EDITION OF THE COMPLETE POEMS OF THOMAS HARDY THE V ariorun1 Edition OF THE Complete Poems OF THOMAS HARDY EDITED BY James Gibson M THE VARIORUM EDITION OF THE COMPLETE POEMS OF THOMAS HARDY Poems 1-919, 925--6, 929-34 and 943, Thomas Hardy's prefaces and notes © Macmillan London Ltd Poems 920-4, 927-8, 935-42 and 944-7 © Trustees of the Hardy Estate Editorial arrangement © Macmillan London Ltd 1976, 1979 Introduction and editorial matter ©James Gibson 1979 Typography © Macmillan London Ltd 1976, 1979 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1979 978-0-333-23773-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. ISBN 978-1-349-03806-0 ISBN 978-1-349-03804-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-03804-6 The Variorum Edition first published in 1979 by MACMILLAN LONDON LIMITED 4 Little Essex Street London WC2R 3LF and Basingstoke Associated companies in Delhi, Dublin, Hong Kong, johannesburg, Lagos, Melbourne, New York, Singapore and Tokyo Typeset by WESTERN PRINTING SERVICES L TO, BRISTOL Contents LIST OF MANUSCRIPT My Cicely 51 ILLUSTRATIONS page xvii Her Immortality 55 INTRODUCTION XIX The Ivy-Wife 57 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS XXXlll A Meeting with Despair 57 NOTES FOR USERS OF THE Unknowing 58 VARIORUM XXXV Friends Beyond 59 To Outer Nature 61 Domicilium 3 Thoughts of Phena 62 Middle-Age Enthusiasms 63 Wessex Poems and Other Verses In a Wood 64 Preface 6 To a Lady 65 The Temporary the All 7 To a Motherless Child 65 Amabel 8 Nature's Questioning 66 Hap 9 The Impercipient 67 In Vision I Roamed 9 At an Inn 68 At a Bridal 10 The Slow Nature 69 Postponement 11 In a Eweleaze near Weatherbury 70 A Confession to a Friend in Trouble 11 The Bride-Night Fire 71 Neutral Tones 12 Heiress and Architect 75 She at His Funeral 12 The Two Men 77 Her Initials 13 Lines 79 Her Dilemma 13 I Look Into My Glass 81 Revulsion 14 She, to Him I 14 Poems of the Past and the Present She, to Him II 15 Preface 84 She, to Him III 15 V.R. -

Wessex Tales

Class 5 Thomas Hardy’s Short Stories The Withered Arm The Distracted Preacher •"How I Built Myself A House" (1865) •"The Winters and the Palmleys" (1891) •"Destiny and a Blue Cloak" (1874) •"For Conscience' Sake" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies) •"The Thieves Who Couldn't Stop Sneezing" (1877) •"Incident in Mr. Crookhill's Life"(1891) •"The Duchess of Hamptonshire" (1878) (collected in A Group of Noble •"The Doctor's Legend" (1891) Dames) •"Andrey Satchel and the Parson and Clerk" (1891) •"The Distracted Preacher" (1879) (collected in Wessex Tales) •"The History of the Hardcomes" (1891) •"Fellow-Townsmen" (1880) (collected in Wessex Tales) •"Netty Sargent's Copyhold" (1891) •"The Honourable Laura" (1881) (collected in A Group of Noble Dames) •"On The Western Circuit" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies) •"What The Shepherd Saw" (1881) (collected in A Changed Man and •"A Few Crusted Characters: Introduction" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Other Stories) Ironies) •"A Tradition of Eighteen Hundred and Four" (1882) (collected in Wessex •"The Superstitious Man's Story" (1891) Tales) •"Tony Kytes, the Arch-Deceiver" (1891) •"The Three Strangers" (1883) (collected in Wessex Tales) •"To Please His Wife (nl)" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies) •"The Romantic Adventures of a Milkmaid" (1883) (collected in A Changed •"The Son's Veto" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies) Man and Other Stories) •"Old Andrey's Experience as a Musician" (1891) •"Interlopers at the Knap" (1884) (collected in Wessex Tales) •"Our Exploits