Religion in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE NAMES of OLD-ENGLISH MINT-TOWNS: THEIR ORIGINAL FORM and MEANING and THEIR EPIGRAPHICAL CORRUPTION—Continued

THE NAMES OF OLD-ENGLISH MINT-TOWNS: THEIR ORIGINAL FORM AND MEANING AND THEIR EPIGRAPHICAL CORRUPTION—Continued. BY ALFRED ANSCOMBE, F.R.HIST.SOC. II. THE NAMES OF OLD-ENGLISH MINT-TOWNS WHICH OCCUR IN THE SAXON CHRONICLES. CHAPTER II (L—Z). 45. Leicester. of Ligera ceastre " 917, K. The peace is broken by Danes — -ere- D ; -ra- B ; -re- C. " set Ligra ceastre' 918, C. The Lady Ethelfleda gets peaceful possession of the burg Legra-, B ; Ligran-, D. " Ligora ceaster " 942, ft. One of the Five Burghs of the Danes. -era-, B, C ; -ere- D. " jet Legra ceastre 943, D. Siege laid by King Edmund. The syllables -ora, -era, are worn fragments of wara, the gen. pi. of warn. This word has been explained already; v. 26, Canterbury, Part II, vol. ix, pp. 107, 108. Ligora.-then equals Ligwara-ceaster, i.e., the city of the Lig-waru. For the falling out of w Worcester (<Wiog- ora-ceaster) Canterbury (< Cant wara burh) and Nidarium (gen. pi. ; < Niduarium) may be compared. The distinction between the Old-English forms of Leicester and Chester lies in the presence or absence of the letter r. The meaning of #Ligwaru, the Ligfolk, has not yet been deter- mined owing- to the fact that Old-English scholars have not consulted o o their Welsh fellow-workers. In old romance the name for the central Naes of Old-English Mint-towns in the Saxon Chronicles. parts of England south of the Humber and Mersey is " Logres." This is Logre with the addition of the Norman-French 5 of the nominative case. -

Protestant and Catholic Cooperation in Early Modern England Lisa Clark Diller Southern Adventist University, [email protected]

Southern Adventist University KnowledgeExchange@Southern Faculty Works History and Political Studies Department 2008 Protestant and Catholic Cooperation in Early Modern England Lisa Clark Diller Southern Adventist University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/facworks_hist Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Diller, Lisa Clark, "Protestant and Catholic Cooperation in Early Modern England" (2008). Faculty Works. 10. https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/facworks_hist/10 This Conference Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the History and Political Studies Department at KnowledgeExchange@Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of KnowledgeExchange@Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Protestant and Catholic Cooperation in Early Modern England The reign of James II gave English Catholics a chance to interact much more intentionally with their Protestant fellow citizens. The rich debate and mutual analysis that ensued with James’s lifting of the censorship of Catholic printing and penal laws changed assumptions, terminology, and expectations regarding religious and civil practices. A more comprehensive articulation of what should be expected of citizens was the result of these debates and English political life after 1689 provided a wider variety of possibilities for trans- denominational cooperation in social and political enterprises. The continuing importance of anti-Catholicism in the attitudes of English Protestants has been emphasized by historians from John Miller to Tim Harris.123456 Without denying this, I argue that the content and quality of this anti-Catholicism was changing and that too great a focus on the mutual antagonism undermines the significant elements of interaction, cooperation and influence. -

West Midlands European Regional Development Fund Operational Programme

Regional Competitiveness and Employment Objective 2007 – 2013 West Midlands European Regional Development Fund Operational Programme Version 3 July 2012 CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 – 5 2a SOCIO-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS - ORIGINAL 2.1 Summary of Eligible Area - Strengths and Challenges 6 – 14 2.2 Employment 15 – 19 2.3 Competition 20 – 27 2.4 Enterprise 28 – 32 2.5 Innovation 33 – 37 2.6 Investment 38 – 42 2.7 Skills 43 – 47 2.8 Environment and Attractiveness 48 – 50 2.9 Rural 51 – 54 2.10 Urban 55 – 58 2.11 Lessons Learnt 59 – 64 2.12 SWOT Analysis 65 – 70 2b SOCIO-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS – UPDATED 2010 2.1 Summary of Eligible Area - Strengths and Challenges 71 – 83 2.2 Employment 83 – 87 2.3 Competition 88 – 95 2.4 Enterprise 96 – 100 2.5 Innovation 101 – 105 2.6 Investment 106 – 111 2.7 Skills 112 – 119 2.8 Environment and Attractiveness 120 – 122 2.9 Rural 123 – 126 2.10 Urban 127 – 130 2.11 Lessons Learnt 131 – 136 2.12 SWOT Analysis 137 - 142 3 STRATEGY 3.1 Challenges 143 - 145 3.2 Policy Context 145 - 149 3.3 Priorities for Action 150 - 164 3.4 Process for Chosen Strategy 165 3.5 Alignment with the Main Strategies of the West 165 - 166 Midlands 3.6 Development of the West Midlands Economic 166 Strategy 3.7 Strategic Environmental Assessment 166 - 167 3.8 Lisbon Earmarking 167 3.9 Lisbon Agenda and the Lisbon National Reform 167 Programme 3.10 Partnership Involvement 167 3.11 Additionality 167 - 168 4 PRIORITY AXES Priority 1 – Promoting Innovation and Research and Development 4.1 Rationale and Objective 169 - 170 4.2 Description of Activities -

(English-Kreyol Dictionary). Educa Vision Inc., 7130

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 401 713 FL 023 664 AUTHOR Vilsaint, Fequiere TITLE Diksyone Angle Kreyol (English-Kreyol Dictionary). PUB DATE 91 NOTE 294p. AVAILABLE FROM Educa Vision Inc., 7130 Cove Place, Temple Terrace, FL 33617. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Vocabularies /Classifications /Dictionaries (134) LANGUAGE English; Haitian Creole EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Alphabets; Comparative Analysis; English; *Haitian Creole; *Phoneme Grapheme Correspondence; *Pronunciation; Uncommonly Taught Languages; *Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS *Bilingual Dictionaries ABSTRACT The English-to-Haitian Creole (HC) dictionary defines about 10,000 English words in common usage, and was intended to help improve communication between HC native speakers and the English-speaking community. An introduction, in both English and HC, details the origins and sources for the dictionary. Two additional preliminary sections provide information on HC phonetics and the alphabet and notes on pronunciation. The dictionary entries are arranged alphabetically. (MSE) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** DIKSIONt 7f-ngigxrzyd Vilsaint tick VISION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement EDU ATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS CENTER (ERIC) MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization originating it. \hkavt Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality. BEST COPY AVAILABLE Points of view or opinions stated in this document do not necessarily represent TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES official OERI position or policy. INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." 2 DIKSYCAlik 74)25fg _wczyd Vilsaint EDW. 'VDRON Diksyone Angle-Kreyal F. Vilsaint 1992 2 Copyright e 1991 by Fequiere Vilsaint All rights reserved. -

Writing About the Ymage in Fifteenth-Century England*

Writing about the ymage in fifteenth-century England* Marjorie Munsterberg Considerable scholarly attention has been given to the ways in which writing about art developed in Renaissance Italy. Michael Baxandall and Robert Williams especially have studied how still-familiar methods of visual description and analysis were created from classical texts as well as contemporary studio talk. This new language spread rapidly through Europe and, over the course of the sixteenth century, overwhelmed every other approach to the visual arts. By the start of the seventeenth century, it had become the only acceptable source of serious visual analysis, a position it still holds in much of art history.1 I would like to examine an earlier English tradition in which both instructions for how to look at visual objects and historical accounts of viewers looking describe something very different. Beginning in the late fourteenth century and continuing through the fifteenth century, Lollard and other reform movements made the use of religious images a * Translations of the Middle English texts are available as an appendix in pdf. Click here. All websites were accessed on 9 December 2019. The amount of scholarly literature about fifteenth-century English religious writings that has been published in the past few decades is staggering. Like others who write about this topic, I am deeply indebted to the pioneering scholarship of the late Margaret Aston as well as that of Anne Hudson, Emeritus Professor of Medieval English, University of Oxford, and Fiona Somerset, Professor of English, University of Connecticut at Storrs. Professor Daniel Sheerin, Professor Emeritus, University of Notre Dame, was extraordinarily generous in response to my inquiries about the history of analysing painting in terms of line and colour. -

Renaissance Quarterly Books Received, October–December 2013

Renaissance Quarterly Books Received, October–December 2013 Ahnert, Ruth. The Rise of Prison Literature in the Sixteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013. x + 222 pp. $90. ISBN: 978-1-107-04030-4. Allen, Gemma. The Cooke Sisters: Education, Piety and Politics in Early Modern England. Politics, Culture and Society in Early Modern Britain. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013. xi + 274 pp. $105. ISBN: 978-0-7190-8833-9. Amelang, James S. Parallel Histories: Muslims and Jews in Inquisitorial Spain. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2013. xi + 208 pp. $25.95. ISBN: 978-0-8071-5410-6. Areford, David. Art of Empathy: The Mother of Sorrows in Northern Renaissance Art and Devotion. Exh. Cat. Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens, 26 November 2013–16 February 2014. London: D. Giles Ltd, 2013. 64 pp. $17.95. ISBN: 978-1-907804-26-7. Aricò, Nicola. Architettura del tardo Rinascimento in Sicilia: Giovannangelo Montorsoli a Messina (1547-57). Biblioteca’“Archivum Romanicum” Serie 1: Storia, Letteratura, Paleografia 422. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 2013. xiv + 224 pp. + 8 color pls. €28. ISBN: 978-88-222-6268- 4. Arner, Lynn. Chaucer, Gower, and the Vernacular Rising: Poetry and the Problem of the Populace After 1381. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2013. ix + 198 pp. $64.95. ISBN: 978-0-271-05893-1. Backscheider, Paula R. Elizabeth Singer Rowe and the Development of the English Novel. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013. xiii + 304 pp. $50. ISBN: 978-1-4214-0842-2. Baker, Geoff. Reading and Politics in Early Modern England: The Mental World of a Seventeenth-Century Catholic Gentleman. -

THE REFORMATION in LEICESTER and LEICESTERSHIRE, C.1480–1590 Eleanor Hall

THE REFORMATION IN LEICESTER AND LEICESTERSHIRE, c.1480–1590 Eleanor Hall Since its arrival in England, never did Christianity undergo such a transformation as that of the Reformation. By the end of the sixteenth century the official presence of Catholicism had almost entirely disappeared in favour of Protestantism, the permanent establishment of which is still the institutional state religion. This transformation, instigated and imposed on the population by a political elite, had a massive impact on the lives of those who endured it. In fact, the progression of these religious developments depended on the compliance of the English people, which in some regions was often absent. Indeed, consideration must be given to the impact of the Reformation on these localities and social groups, in which conservatism and nostalgia for the traditional faith remained strong. In spite of this, the gradual acceptance of Protestantism by the majority over time allowed its imposition and the permanent establishment of the Church of England. Leicestershire is a county in which significant changes took place. This paper examines these changes and their impact on, and gradual acceptance by, the various religious orders, secular clergy, and the laity in the town and county. Important time and geographical comparisons will be drawn in consideration of the overall impact of the Reformation, and the extent to which both clergy and laity conformed to the religious changes imposed on them, and managed to retain their religious devotion in the process. INTRODUCTION The English Reformation is one of the periods in history that attracts a high level of interest and debate. -

East Meets West

East Meets West The stories of the remarkable men and women from the East and the West who built a bridge across a cultural divide and introduced Meditation and Eastern Philosophy to the West John Adago SHEPHEARD-WALWYN (PUBLISHERS) LTD © John Adago 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher, Shepheard-Walwyn (Publishers) Ltd www.shepheard-walwyn.co.uk First published in 2014 by Shepheard-Walwyn (Publishers) Ltd 107 Parkway House, Sheen Lane, London SW14 8LS www.shepheard-walwyn.co.uk British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-85683-286-4 Typeset by Alacrity, Chesterfield, Sandford, Somerset Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by imprintdigital.com Contents Photographs viii Acknowledgements ix Introduction 1 1 Seekers of Truth 3 2 Gurdjieff in Russia 7 3 P.D. Ouspensky: The Work Comes to London 15 4 Willem A. Nyland: Firefly 27 5 Forty Days 31 6 Andrew MacLaren: Standing for Justice 36 7 Leon MacLaren: A School is Born 43 8 Adi Shankara 47 9 Shri Gurudeva – Swami Brahmananda Saraswati 51 10 Vedanta and Western Philosophy 57 11 Maharishi Mahesh Yogi: Flower Power – The Spirit of the Sixties 62 12 Swami Muktananda: Growing Roses in Concrete 70 13 Shantananda Saraswati 77 14 Dr Francis Roles: Return to the Source 81 15 Satsanga: Good Company 88 16 Joy Dillingham and Nicolai Rabeneck: Guarding the Light 95 17 Last Days 106 18 The Bridge 111 The Author 116 Appendix 1 – Words of the Wise 129 Appendix 2 – The Enneagram 140 Appendix 3 – Philosophy and Christianity 143 Notes 157 Bibliography 161 ~vii~ Photographs G.I. -

Religion in England and Wales 2011

Religion in England and Wales 2011 Key points Despite falling numbers Christianity remains the largest religion in England and Wales in 2011. Muslims are the next biggest religious group and have grown in the last decade. Meanwhile the proportion of the population who reported they have no religion has now reached a quarter of the population. • In the 2011 Census, Christianity was the largest religion, with 33.2 million people (59.3 per cent of the population). The second largest religious group were Muslims with 2.7 million people (4.8 per cent of the population). • 14.1 million people, around a quarter of the population in England and Wales, reported they have no religion in 2011. • The religion question was the only voluntary question on the 2011 census and 7.2 per cent of people did not answer the question. • Between 2001 and 2011 there has been a decrease in people who identify as Christian (from 71.7 per cent to 59.3 per cent) and an increase in those reporting no religion (from 14.8 per cent to 25.1 per cent). There were increases in the other main religious group categories, with the number of Muslims increasing the most (from 3.0 per cent to 4.8 per cent). • In 2011, London was the most diverse region with the highest proportion of people identifying themselves as Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu and Jewish. The North East and North West had the highest proportion of Christians and Wales had the highest proportion of people reporting no religion. • Knowsley was the local authority with the highest proportion of people reporting to be Christians at 80.9 per cent and Tower Hamlets had the highest proportion of Muslims at 34.5 per cent (over 7 times the England and Wales figure). -

45 Working.Qxd

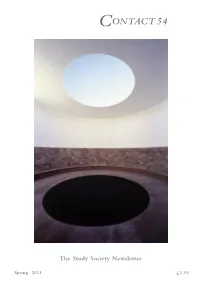

CONTACT 54 The Study Society Newsletter Spring 2011 £3.00 Contact The Study Society Newsletter Wring Out My Clothes Such love does the sky now pour, that whenever I stand in a field, I have to wring out the light when I get home. St Francis of Assisi From, for lovers of god everywhere Hay House, 2009 Cover Illustration James Turrell .© ‘Sky-space’ installation in the Roden Crater, Arizona. The Roden Crater is an extinct volcanic cinder cone, situated at an elevation of approximately 5,400 feet in the San Francisco Volcanic Field near Arizona's Painted Desert and the Grand Canyon. The 600 foot tall red and black cinder cone is being turned into a monumental work of art and naked eye observatory by the artist James Turrell, who says: . in this stage set of geologic time, I wanted to make spaces that engaged celestial events in light so that the spaces performed like a music of the spheres — in light. The sequence of spaces, leading up to the final large space at the top of the crater, magnifies events. The work I do intensifies the experience of light by isolating it and occluding light from events not looked at. (See more at www.rodencrater.com) CONTENTS 3. The Universe as a Hologram Michael Talbot 9. Nothing Obscures Consciousness Rupert Spira 12. Three Graces James Witchalls 15. Holman Hunt and the Light of Consciousness Fiona Stuart 17. Writing a poem, living a life Tony Brignull 19. Sometimes a Light surprises Heather Gibbs 20. ‘Dawning of the clear light’ Peter & Elizabeth Fenwick 22. -

45 Working.Qxd

Contact The Study Society Newsletter Seeking a grand unification of matter, mind and spirit S. M. Jaiswal The Games Mouravieff & the secret of the source Meditating with your children No. 61 Summer 2013 FREE TO MEMBERS, OTHERS £5.00 Contact The Study Society Newsletter Question about loss of direction Question: What is the right effort involved in remembering what one has forgotten? Dr. Roles. I think it is to be silent for a moment. In that silence one collects oneSelf – one comes to oneSelf. It seems to be the one effort that works, for a sense of direction comes from within. One aspect of this is to give up all problems, all thinking, all mental activity and do what you have to do as if you were under orders – simply stepping out when you are walking, unlocking a door with attention, nothing else going on at all. That is so very refreshing; one is just a servant of the Param-Atman. This becomes very interesting if you take the Gospels psychologically. You remember Christ saying: Not everyone that saith unto me, Lord, Lord, shall enter the kingdom of heaven; but he that doeth the will of my Father which is in heaven. Many will say to me in that day, Lord, Lord, have we not prophesied in thy name? and in thy name have cast out devils? and in thy name done many wonderful works? And then will I profess unto them, I never knew you: depart from me, ye that work iniquity. (Matthew 7: 21–23) Now meditators, just doing empty repetition, just repeating the Name, are saying ‘Lord, Lord’. -

Religion and Geography

Park, C. (2004) Religion and geography. Chapter 17 in Hinnells, J. (ed) Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion. London: Routledge RELIGION AND GEOGRAPHY Chris Park Lancaster University INTRODUCTION At first sight religion and geography have little in common with one another. Most people interested in the study of religion have little interest in the study of geography, and vice versa. So why include this chapter? The main reason is that some of the many interesting questions about how religion develops, spreads and impacts on people's lives are rooted in geographical factors (what happens where), and they can be studied from a geographical perspective. That few geographers have seized this challenge is puzzling, but it should not detract us from exploring some of the important themes. The central focus of this chapter is on space, place and location - where things happen, and why they happen there. The choice of what material to include and what to leave out, given the space available, is not an easy one. It has been guided mainly by the decision to illustrate the types of studies geographers have engaged in, particularly those which look at spatial patterns and distributions of religion, and at how these change through time. The real value of most geographical studies of religion in is describing spatial patterns, partly because these are often interesting in their own right but also because patterns often suggest processes and causes. Definitions It is important, at the outset, to try and define the two main terms we are using - geography and religion. What do we mean by 'geography'? Many different definitions have been offered in the past, but it will suit our purpose here to simply define geography as "the study of space and place, and of movements between places".