John Blow, Jesus Seeing the Multitudes, Ed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCOM182 Lent & Eastertide

LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC Lent, Holy Week, and Eastertide 2018 GRACE CATHEDRAL 2 LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC GRACE CATHEDRAL SAN FRANCISCO LENT, HOLY WEEK, AND EASTERTIDE 2018 11 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LÆTARE Introit: Psalm 32:1-6 – Samuel Wesley Service: Collegium Regale – Herbert Howells Psalm 107 – Thomas Attwood Walmisley O pray for the peace of Jerusalem - Howells Drop, drop, slow tears – Robert Graham Hymns: 686, 489, 473 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Benjamin Bachmann Psalm 107 – Lawrence Thain Canticles: Evening Service in A – Herbert Sumsion Anthem: God so loved the world – John Stainer Hymns: 577, 160 15 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Canticles: Third Service – Philip Moore Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Hymns: 678, 474 18 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LENT 5 Introit: Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Service: Missa Brevis – Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina Psalm 51 – T. Tertius Noble Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Motet: The crown of roses – Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Hymns: 471, 443, 439 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 51 – Jeffrey Smith Canticles: Short Service – Orlando Gibbons Anthem: Aus tiefer Not – Felix Mendelssohn Hymns: 141, 151 3 22 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: William Byrd Psalm 103 – H. Walford Davies Canticles: Fauxbourdons – Thomas -

Dr. John Blow (1648-1708) Author(S): F

Dr. John Blow (1648-1708) Author(s): F. G. E. Source: The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol. 43, No. 708 (Feb. 1, 1902), pp. 81-88 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3369577 Accessed: 05-12-2015 16:35 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.189.170.231 on Sat, 05 Dec 2015 16:35:56 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE MUSICAL TIMES.-FEBRUARY I, 1902. 81 THE MUSICAL composerof some fineanthems and known to TIMES everybodyas the authorof the ' Grand chant,'- AND SINGING-CLASS CIRCULAR. and William Turner. These three boys FEBRUARY I, 1902. collaboratedin the productionof an anthem, therebycalled the Club Anthem,a settingof the words ' I will always give thanks,'each young gentlemanbeing responsible for one of its three DR. JOHN BLOW movements. The origin of this anthem is variouslystated; but the juvenile joint pro- (1648-I7O8). -

Restoration Keyboard Music

Restoration Keyboard Music This series of concerts is based on my researches into 17th century English keyboard music, especially that of Matthew Locke and his Restoration colleagues, Albertus Bryne and John Roberts. Concert 1. "Melothesia restored". The keyboard music by Matthew Locke and his contemporaries. Given at the David Josefowitz Recital Hall, Royal Academy of Music on Tuesday SEP 30, 2003 Music by Matthew Locke (c.1622-77), Frescobaldi (1583-1643), Chambonnières (c.1602-72), William Gregory (fl 1651-87), Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625), Froberger (1616-67), Albert Bryne (c.1621-c.1670) This programmes sets a selection of Matthew Locke’s remarkable keyboard music within the wider context of seventeenth century keyboard playing. Although Locke confessed little admiration for foreign musical practitioners, he is clearly endebted to European influences. The un-measued prelude style which we find in the Prelude of the final C Major suite, for example, suggest a French influence, perhaps through the lutenists who came to London with the return of Charles II. Locke’s rhythmic notation belies the subtle inflections and nuances of what we might call the international style which he first met as a young man visiting the Netherlands with his future regal employer. One of the greatest keyboard players of his day, Froberger, visited London before 1653 and, not surprisingly, we find his powerful personality behind several pieces in Locke’s pioneering publication, Melothesia. As for other worthy composers of music for the harpsichord and organ, we have Locke's own testimony in his written reply to Thomas Salmon in 1672, where, in addition to Froberger, he mentions Frescobaldi and Chambonnières with the Englishmen John Bull, Orlando Gibbons, Albertus Bryne (his contemporary and organist of Westminster Abbey) and Benjamin Rogers. -

Appendix: Catalogue of Restoration Music Manuscripts Bibliography

Musical Creativity in Restoration England REBECCA HERISSONE Appendix: Catalogue of Restoration Music Manuscripts Bibliography Secondary Sources Ashbee, Andrew, ‘The Transmission of Consort Music in Some Seventeenth-Century English Manuscripts’, in Andrew Ashbee and Peter Holman (eds.), John Jenkins and his Time: Studies in English Consort Music (Oxford: Clarendon, 1996), 243–70. Ashbee, Andrew, Robert Thompson and Jonathan Wainwright, The Viola da Gamba Society Index of Manuscripts Containing Consort Music, 2 vols. (Aldershot and Burlington: Ashgate, 2001–8). Bailey, Candace, ‘Keyboard Music in the Hands of Edward Lowe and Richard Goodson I: Oxford, Christ Church Mus. 1176 and Mus. 1177’, Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle, 32 (1999), 119–35. ‘New York Public Library Drexel MS 5611: English Keyboard Music of the Early Restoration’, Fontes artis musicae, 47 (2000), 51–67. Seventeenth-Century British Keyboard Sources, Detroit Studies in Music Bibliography, 83 (Warren: Harmonie Park Press, 2003). ‘William Ellis and the Transmission of Continental Keyboard Music in Restoration England’, Journal of Musicological Research, 20 (2001), 211–42. Banks, Chris, ‘British Library Ms. Mus. 1: A Recently Discovered Manuscript of Keyboard Music by Henry Purcell and Giovanni Battista Draghi’, Brio, 32 (1995), 87–93. Baruch, James Charles, ‘Seventeenth-Century English Vocal Music as reflected in British Library Additional Manuscript 11608’, unpublished PhD dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (1979). Beechey, Gwilym, ‘A New Source of Seventeenth-Century Keyboard Music’, Music & Letters, 50 (1969), 278–89. Bellingham, Bruce, ‘The Musical Circle of Anthony Wood in Oxford during the Commonwealth and Restoration’, Journal of the Viola da Gamba Society of America, 19 (1982), 6–71. -

Jean Clay Radice, Organ Jean Clay Radice

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 8-31-2012 Faculty Recital: Jean Clay Radice, organ Jean Clay Radice Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Radice, Jean Clay, "Faculty Recital: Jean Clay Radice, organ" (2012). All Concert & Recital Programs. 3894. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/3894 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Faculty Recital: Jean Clay Radice, organ Ford Hall Friday, August 31, 2012 7:00 p.m. Program Four Centuries of Organ Music in the Anglican Tradition Voluntary for Double Organ Henry Purcell (1659-1695) Voluntary I in D Major William Boyce (1711-1779) On a Theme of Orlando Gibbons (Song 34) Charles Villiers Stanford The Angels' Song, Op.105, No.1 (1852-1924) Intermezzo Founded Upon an Irish Air, Op.189 On a Theme of Orlando Gibbons (Song 22), Op.105, No.4 Three Preludes Founded on Welsh Hymn Ralph Vaughan Williams Tunes (1872-1958) I. Bryn Calfaria II. Rhosymedre (or "Lovely") III. Hyfrydol Psalm-Prelude, Op.32, No.2 Herbert Howells Dalby's Fancy, from Two Pieces for Organ Manuals (1892-1983) Only Prelude on "Slane" Gerry Hancock (1934-2012) Alleluyas Simon Preston At his feet the six-winged Seraph; Cherubim with (b. 1938) sleepless eye, Veil their faces to the Presence, as with ceaseless voice they cry, Alleluya, Alleluya, Alleluya, Lord most high. -

Robert Shay (University of Missouri)

Manuscript Culture and the Rebuilding of the London Sacred Establishments, 1660- c.17001 By Robert Shay (University of Missouri) The opportunity to present to you today caused me to reflect on the context in which I began to study English music seriously. As a graduate student in musicology, I found myself in a situation I suspect is rare today, taking courses mostly on Medieval and Renaissance music. I learned to transcribe Notre Dame polyphony, studied modal theory, and edited Italian madrigals, among other pursuits. I had come to musicology with a background in singing and choral conducting, and had grown to appreciate—as a performer—what I sensed were the unique characteristics of English choral music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It was a seminar on the stile antico that finally provided an opportunity to bring together earlier performing and newer research interests. I had sung a few of Henry Purcell’s polyphonic anthems (there really are only a few), liked them a lot, and wondered if they were connected to earlier music by Thomas Tallis, William Byrd, and others, music which I soon came to learn Purcell knew himself. First for the above-mentioned seminar and then for my dissertation, I cast my net broadly, trying to learn as much as I could about Purcell and his connections to earlier English music. I quickly came to discover that the English traditions were, in almost every respect, distinct from the Continental ones I had been studying, ranging from how counterpoint was taught (or not taught) 1 This paper was delivered at a March 2013 symposium at Western Illinois University with the title, “English Cathedral Music and the Persistence of the Manuscript Tradition.” The present version includes some subsequent revisions and a retitling that I felt more accurately described the paper. -

Purcell's Early Years Background Henry Purcell Is Believed to Have Been Born in 1659 Near Westminster Abbey in London England

webpage1 Page 1 of 2 Purcell's Early Years Background Henry Purcell is believed to have been born in 1659 near Westminster Abbey in London England. Henry's parents are believed to be Henry the court composer, Senior, and his wife Elizabeth. Little is known about our hero's childhood, as might be suggested from the speculation over his origins. Many of the following statements are based on related facts that given time and place, may be used to hypothesize the specifics of where and what Henry was doing at a specific point in time. Henry Senior and his brother Thomas were both actively involved as court musicians in London. Henry Senior died early, likely as a victim of the plague that devastated much of London in 1666. Thus, Thomas Purcell, our hero's uncle, had more influence on the early years of the young musician than did his father. Thomas must have exposed Henry to music thus prompting Henry's mother, Elizabeth, to send her son off to become a choirboy in the Chapel Royal: "Elizabeth Purcell was a single mother on a limited incomeso the opportunity for one of her boys to be given a decent education, clothed and fed must have been most welcome." (King, 59) It was common for a boy between the ages of eight and nine to become a chorister and continue his training until puberty when the voice began to break. Probable Training In 1668 at the age of about eight Henry became a member of the boy's choir at the Chapel Royal under the supervision of Henry Cooke, Master of the Children. -

The London St. Cecilia's Day Festivals and the Cultivation of a Godly Nation Paula Horner a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfil

The London St. Cecilia’s Day Festivals and the Cultivation of a Godly Nation Paula Horner A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2012 JoAnn Taricani, Chair Stephen Rumph Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE 5 Celebrating English Artistry CHAPTER TWO 24 Music, Church and State CHAPTER THREE 38 From Secular Saint to Civil Sermon CONCLUSION 68 APPENDIX I: 70 Movements and performing forces of Blow’s 1691 ode APPENDIX II: 72 Movements and performing forces of Purcell’s 1692 ode BIBLIOGRAPHY 74 i Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to JoAnn Taricani, whose unwavering support and frank criticism have urged this thesis to its current state. I would also like to thank Stephen Rumph, whose refusal to pull punches is both notorious and well-appreciated. My colleagues at the University of Washington have been invaluable sources of encouragement and scholarly inspiration; I thank Kirsten Sullivan for her keen critical mind, Leann Wheless Martin for her curiosity and refreshing groundedness, Sarah Shewbert for her unbridled enthusiasm, and Samantha Dawn Englander for her passion and solidarity. Additional thanks extend to my family and friends whose support has led me here. Finally, a particular expression of gratitude goes to Kris Harper, for his unflagging patience and relentless faith in me. ii INTRODUCTION In the late seventeenth century, major cities across England marked St. Cecilia’s Day with a musical celebration. While Oxford, Winchester, and Salisbury hosted these yearly festivals with some frequency, the tradition was established most firmly in London, where St. -

Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra Sunday / July 18 / 4:00Pm / Venetian Theater

SUMMER 2 0 2 1 Contents 2 Welcome to Caramoor / Letter from the CEO and Chairman 3 Summer 2021 Calendar 8 Eat, Drink, & Listen! 9 Playing to Caramoor’s Strengths by Kathy Schuman 12 Meet Caramoor’s new CEO, Edward J. Lewis III 14 Introducing in“C”, Trimpin’s new sound art sculpture 17 Updating the Rosen House for the 2021 Season by Roanne Wilcox PROGRAM PAGES 20 Highlights from Our Recent Special Events 22 Become a Member 24 Thank You to Our Donors 32 Thank You to Our Volunteers 33 Caramoor Leadership 34 Caramoor Staff Cover Photo: Gabe Palacio ©2021 Caramoor Center for Music & the Arts General Information 914.232.5035 149 Girdle Ridge Road Box Office 914.232.1252 PO Box 816 caramoor.org Katonah, NY 10536 Program Magazine Staff Caramoor Grounds & Performance Photos Laura Schiller, Publications Editor Gabe Palacio Photography, Katonah, NY Adam Neumann, aanstudio.com, Design gabepalacio.com Tahra Delfin,Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Brittany Laughlin, Director of Marketing & Communications Roslyn Wertheimer, Marketing Manager Sean Jones, Marketing Coordinator Caramoor / 1 Dear Friends, It is with great joy and excitement that we welcome you back to Caramoor for our Summer 2021 season. We are so grateful that you have chosen to join us for the return of live concerts as we reopen our Venetian Theater and beautiful grounds to the public. We are thrilled to present a full summer of 35 live in-person performances – seven weeks of the ‘official’ season followed by two post-season concert series. This season we are proud to showcase our commitment to adventurous programming, including two Caramoor-commissioned world premieres, three U.S. -

Gonville & Caius College Chapel Lent Term 2019

GONVILLE & CAIUS COLLEGE CHAPEL LENT TERM 2019 Dean: The Revd Dr Cally Hammond Precentor: Dr Geoffrey Webber Dean’s Vicar: The Revd Canon Dr Nicholas Thistlethwaite Senior Organ Scholar: Luke Fitzgerald Wilfrid Holland Organ Scholar: Kyoko Canaway Sunday 3 March Sunday 10 March 1st Sunday of Lent Choral Evensong & Sermon at 6 pm Choral Evensong at 6 pm Andante tranquillo Felix Mendelssohn Voluntary in G Henry Purcell Preces & Responses John Reading, reconstr. Webber Preces & Responses John Reading, reconstr. Webber Psalm 19 Tone iii/5 Psalm 69.1-22 Tone iv/4 1 Kings 18.22-40; Luke 9.51-62 Jonah 1.1-17; 2.1, 10; Matthew 12.25-42 The Fourth Service Adrian Batten Evening Service in G minor Henry Purcell / D. Roseingrave Elijah and the prophets of Baal (Elijah) Felix Mendelssohn Jonas Giacomo Carissimi Hymns ‘God hath spoken’ (t. 474), 404 Hymns ‘Fierce raged’ (t. EH 541), 354, 383 (ii) Final Amen William Byrd Final Amen William Byrd Prelude in C major (BWV 547) J. S. Bach Cornet Voluntary in A minor John Blow Tuesday 5 March Tuesday 12 March Choral Evensong at 6.30 pm Choral Evensong at 6.30 pm Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier (Op. 65, No. 57) Sigfrid Karg-Elert Herzlich tut mich verlangen (BWV 727) J. S. Bach Preces & Responses John Reading, reconstr. Webber Preces & Responses John Reading, reconstr. Webber Psalm 50 Lloyd Psalm 78 Ouseley / Barnby / Stainer / Goss / Walmisley Genesis 37.12-end; Galatians 2.1-10 Office Hymn 382 Office Hymn 463 (ii) Evening Service in G minor Henry Purcell Evening Service in A flat Edmund Rubbra Bring us, O Lord God William Harris The Light Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco Final Responses Philip Lucas Final Responses Philip Lucas Meditation on Love Unknown Francis Jackson O Gott, du frommer Gott Johannes Brahms Thursday 14 March Choral Eucharist at 6.30 pm Wednesday 6 March Ash Wednesday (Solo voices) Solemn Eucharist with Imposition of Ashes at 6.15 pm Toccata-Kyrie (Messa delli Apostoli) Girolamo Frescobaldi Ach Herr mich armen Sünder (BuxWV 178) Dieterich Buxtehude Missa Sex vocum Giovanni Croce Missa brevis G. -

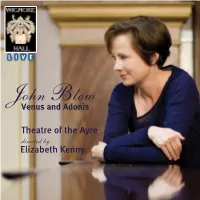

John Blow Venus & Adonis Mp3, Flac

John Blow Venus & Adonis mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Venus & Adonis Country: Germany Released: 2014 Style: Opera, Baroque MP3 version RAR size: 1402 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1126 mb WMA version RAR size: 1630 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 738 Other Formats: XM MMF DTS VOX AU AAC TTA Tracklist Prologue 1 Overture 4:28 2 Behold My Arrows And My Bow (Cupid) 0:49 3 Come Shepherds All, Let's Sing And Play (Shepherdess) 3:18 4 In These Sweet Groves Love Is Not Taught (Cupid) 3:31 5 Cupid's Entry 1:05 Act One 6 Tune For Flutes 2:27 7 Venus!... Adonis!,,, (Adonis, Venus) 1:55 8 Hunter's Music / Hark, Hark, The Rural Music Sounds (Venus) 1:08 9 Adonis Will Not Hunt Today (Adonis) 2:34 10 Come Follow, Follow To The Noblest Game (Chorus Of Huntsmen) 2:45 11 A Dance By A Huntsman 1:25 12 Act Tune 1:42 Act Two 13 You Place With Such Delightful Care (Cupid) 1:42 The Cupid's Lesson 14 The Insolent, The Arrogant (Cupid) 1:18 15 Choose For The Formal Fool (Cupid) 1:42 16 A Dance Of Cupids 1:35 17 Call The Graces (Venus) 1:04 18 Mortals Below, Cupids Above (Chorus Of The Graces) 1:16 19 The Grace's Dance 1:28 20 Gavatt 1:13 21 Sarabrand For The Graces 1:06 22 A Ground 2:17 23 Act Tune 2:24 Act Three 24 Adonis! Adonis! Adonis! (Venus) 6:13 25 With Solemn Pomp Let Mourning Cupids Bear (Venus) 2:23 26 Mourn For Thy Servant, Mighty God Of Love (Chorus) 3:49 Credits Cello [Bass Violin] – Catherine Finnis, Jo Levine*, Richard Campbell, Richard Tunnicliffe Chorus – Choristers Of Westminster Abbey Choir* Chorus Master, Organ – Martin -

Venus and Adonis

0043 CD Booklet RPM.qxd 06-12-2010 09:43 Page 1 ohn low JVenus andB Adonis Theatre of the Ayre Elizabethdirected by Kenny 0043 CD Booklet RPM.qxd 06-12-2010 09:43 Page 2 Theatre of the Ayre Elizabeth Kenny JOHN BLOW 01 Cloe found Amintas lying (A Song for Three Voices) 06.20 02 Ground in G minor for violin and continuo 03.56 MICHEL LAMBERT 03 Vos mépris chaque jour me causent mille alarmes 03.41 ROBERT DE VISÉE 04 Chaconne 05.12 JOHN BLOW Venus anD ADonis 05 OVERTURE 03.37 PROLOGUE 06 Cupid ‘Behold my arrows and my bow’ 07.00 07 Cupid’s Entry 01.14 08 Tune for Flutes 02.33 ACT 1 09 Adonis ‘Venus!’ 02.27 10 Hunters’ Music 03.51 11 Chorus ‘Come follow, follow to the noblest game’ 02.32 12 A Dance by a Huntsman 01.19 13 Act Tune 01.54 ACT 2 14 Cupid ‘You place with such delightful care’ 01.56 15 The Cupids’ Lesson 03.03 2 0043 CD Booklet RPM.qxd 06-12-2010 09:43 Page 3 Cupid and the little Cupids ‘The insolent, the arrogant’ 16 A Dance of the Cupids 01.28 17 Venus ‘Call the Graces’ 01.08 18 Chorus of the Graces ‘Mortals below, Cupids above’ 01.22 19 The Graces’ Dance 01.26 20 Gavatt 00.46 21 Saraband for the Graces 01.22 22 A Ground 01.52 23 Act Tune 02.39 ACT 3 24 Venus ‘Adonis!’ 05.03 25 Venus ‘With solemn pomp let mourning Cupids bear’ 07.05 Theatre of the Ayre Elizabeth Kenny director/theorbo/guitar Venus Sophie Daneman Adonis Roderick Williams Cupid Elin Manahan Thomas Soprano and shepherdess Helen Neeves Alto and shepherd Caroline Sartin Tenor and huntsman Jason Darnell Bass and shepherd Frederick Long Cupids from Salisbury Cathedral