Omsk Hemorrhagic Fever (OHF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mammalia: Rodentia) Around Amasya, Turkey

Z. ATLI ŞEKEROĞLU, H. KEFELİOĞLU, V. ŞEKEROĞLU Turk J Zool 2011; 35(4): 593-598 © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/zoo-0910-4 Cytogenetic characteristics of Microtus dogramacii (Mammalia: Rodentia) around Amasya, Turkey Zülal ATLI ŞEKEROĞLU1,*, Haluk KEFELİOĞLU2, Vedat ŞEKEROĞLU1 1Ordu University, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Department of Biology, 52200 Ordu - TURKEY 2Ondokuz Mayıs University, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Department of Biology, 55139 Kurupelit, Samsun - TURKEY Received: 02.10.2009 Abstract: Th e banding patterns of chromosomes of Microtus dogramacii, a recently described vole species endemic to Turkey, were studied. G-, C-, and Ag-NOR-banded patterns of this species are reported here for the fi rst time. In this study, 2 karyotypical forms were determined. Each form had the same diploid chromosome numbers (2n = 48), but possessed diff erent autosomal morphologies. For this reason, the samples collected from the research area were karyologically separated into 2 groups, cytotype-1 (NF = 50) and cytotype-2 (NF = 52). All chromosomes possessed centromeric/pericentromeric heterochromatin bands in both karyotypical forms. It was shown that the acrocentric chromosomes of pair 8 in cytotype-1 have been transformed into metacentric chromosomes in cytotype-2 through pericentric inversion. Variation in the number of active NORs was also observed, but the modal number of active NORs was 8. Due to the chromosomal variation found in M. dogramacii, the cytogenetic results presented in this study may represent a process of chromosomal speciation. Key words: Microtus dogramacii, karyology, pericentric inversion, Turkey Amasya (Türkiye) çevresindeki Microtus dogramacii (Mammalia: Rodentia)’nin sitogenetik özellikleri Özet: Türkiye için endemik olan yeni tanımlanmış bir tarla faresi, Microtus dogramacii’nin kromozomlarının bantlı örnekleri çalışıldı. -

The Dispersal and Acclimatization of the Muskrat, Ondatra Zibethicus (L.), in Finland

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center Other Publications in Wildlife Management for 1960 The dispersal and acclimatization of the muskrat, Ondatra zibethicus (L.), in Finland Atso Artimo Suomen Riistanhoito-Saatio (Finnish Game Foundation) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdmother Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Artimo, Atso, "The dispersal and acclimatization of the muskrat, Ondatra zibethicus (L.), in Finland" (1960). Other Publications in Wildlife Management. 65. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdmother/65 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Other Publications in Wildlife Management by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. R I 1ST A TIE T L .~1 U ( K A I S U J A ,>""'liSt I " e'e 'I >~ ~··21' \. • ; I .. '. .' . .,~., . <)/ ." , ., Thedi$perscdQnd.a~C:li"'dti~otlin. of ,the , , :n~skret, Ond~trq ~ib.t~i~',{(.h in. Firtland , 8y: ATSO ARTIMO . RllSTATIETEELLISljX JULKAISUJA PAPERS ON GAME RESEARCH 21 The dispersal and acclimatization of the muskrat, Ondatra zibethicus (l.), in Finland By ATSO ARTIMO Helsinki 1960 SUOMEN FIN LANDS R I 1ST A N HOI T O-S A A T I b ] AK TV ARDSSTI FTELSE Riistantutkimuslaitos Viltforskningsinstitutet Helsinki, Unionink. 45 B Helsingfors, Unionsg. 45 B FINNISH GAME FOUNDATION Game Research Institute Helsinki, Unionink. 45 B Helsinki 1960 . K. F. Puromichen Kirjapaino O.-Y. The dispersal and acclimatization of the muskrat, Ondatra zibethicus (L.), in Finland By Atso Artimo CONTENTS I. -

Systematics, Geographic Variation, and Evolution of Snow Voles (Chionomys) Based on Dental Characters

AclaThcriologica 36 (1-2): 1-45,1991. PI, ISSN 0001 -7051 Systematics, geographic variation, and evolution of snow voles (Chionomys) based on dental characters Adam NADACHOWSKI Nadachowski A. 1991. Systematics, geographic variation, and evolution of snow voles (iChiononrys) based on dental characters. Acta theriol. 36: 1 -45. Analysis of dental characters of Chionomys supported by a comparison with biochemical and karyological criteria shows its isolation from Microtus (sensu slricto). Snow voles (Chionomys) consist of two lineages developed separately since the Lower Biharian. The first one has appeared and evolved in Europe (Ch. nivalis lineage) while the second is probably of the Near East or Caucasus origin (Ch. roberli-gud lineage). Variation in dental characters of extant Ch. nivalis permit to reconstruct affinities between particular populations comparable in this respect with biochcniical data. Fossil species traditionally included in the Chionomys group (Microtus matei, M. ttivaloides, M. nivalinns, M. rallicepoides) seem to belong to Microtus sensu striclo. Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals, Polish Academy of Sciences, Sławkowska 17, 31-016 Kraków, Poland Key words', systematics, evolution, Chionomys, dental characters Introduction Teeth have long been inlcnsivcly studied by palaeontologists because they have great value in the identification of species and the investigation of variability, microevolution and phylctic relationships. Abundant fossil record of voles (An’icolidae) from Oualcmary sediments of Eurasia and North America discovered in last decades (see Fejfar and Heinrich 1983, Zakrzewski 1985, Rcpcnning 1987 for summary) provide the opportunity to reconstruct their variation, spcciation and phylogcny more precisely. The major changes in the arvicolids lhat have been documented from the fossil materials involve changes in the cheek leeth (Mi and M3). -

Introduction to Arthropod Groups What Is Entomology?

Entomology 340 Introduction to Arthropod Groups What is Entomology? The study of insects (and their near relatives). Species Diversity PLANTS INSECTS OTHER ANIMALS OTHER ARTHROPODS How many kinds of insects are there in the world? • 1,000,0001,000,000 speciesspecies knownknown Possibly 3,000,000 unidentified species Insects & Relatives 100,000 species in N America 1,000 in a typical backyard Mostly beneficial or harmless Pollination Food for birds and fish Produce honey, wax, shellac, silk Less than 3% are pests Destroy food crops, ornamentals Attack humans and pets Transmit disease Classification of Japanese Beetle Kingdom Animalia Phylum Arthropoda Class Insecta Order Coleoptera Family Scarabaeidae Genus Popillia Species japonica Arthropoda (jointed foot) Arachnida -Spiders, Ticks, Mites, Scorpions Xiphosura -Horseshoe crabs Crustacea -Sowbugs, Pillbugs, Crabs, Shrimp Diplopoda - Millipedes Chilopoda - Centipedes Symphyla - Symphylans Insecta - Insects Shared Characteristics of Phylum Arthropoda - Segmented bodies are arranged into regions, called tagmata (in insects = head, thorax, abdomen). - Paired appendages (e.g., legs, antennae) are jointed. - Posess chitinous exoskeletion that must be shed during growth. - Have bilateral symmetry. - Nervous system is ventral (belly) and the circulatory system is open and dorsal (back). Arthropod Groups Mouthpart characteristics are divided arthropods into two large groups •Chelicerates (Scissors-like) •Mandibulates (Pliers-like) Arthropod Groups Chelicerate Arachnida -Spiders, -

Historical Agricultural Changes and the Expansion of a Water Vole

Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 212 (2015) 198–206 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment journa l homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/agee Historical agricultural changes and the expansion of a water vole population in an Alpine valley a,b,c,d, a c c e Guillaume Halliez *, François Renault , Eric Vannard , Gilles Farny , Sandra Lavorel d,f , Patrick Giraudoux a Fédération Départementale des Chasseurs du Doubs—rue du Châtelard, 25360 Gonsans, France b Fédération Départementale des Chasseurs du Jura—route de la Fontaine Salée, 39140 Arlay, France c Parc National des Ecrins—Domaine de Charance, 05000 Gap, France d Laboratoire Chrono-Environnement, Université de Franche-Comté/CNRS—16 route de, Gray, France e Laboratoire d'Ecologie Alpine, Université Grenoble Alpes – BP53 2233 rue de la Piscine, 38041 Grenoble, France f Institut Universitaire de France, 103 boulevard Saint-Michel, 75005 Paris, France A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Small mammal population outbreaks are one of the consequences of socio-economic and technological Received 20 January 2015 changes in agriculture. They can cause important economic damage and generally play a key role in food Received in revised form 30 June 2015 webs, as a major food resource for predators. The fossorial form of the water vole, Arvicola terrestris, was Accepted 8 July 2015 unknown in the Haute Romanche Valley (French Alps) before 1998. In 1998, the first colony was observed Available online xxx at the top of a valley and population spread was monitored during 12 years, until 2010. -

Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever

Crimean-Congo Importance Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is caused by a zoonotic virus that Hemorrhagic seems to be carried asymptomatically in animals but can be a serious threat to humans. This disease typically begins as a nonspecific flu-like illness, but some cases Fever progress to a severe, life-threatening hemorrhagic syndrome. Intensive supportive care is required in serious cases, and the value of antiviral agents such as ribavirin is Congo Fever, still unclear. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV) is widely distributed Central Asian Hemorrhagic Fever, in the Eastern Hemisphere. However, it can circulate for years without being Uzbekistan hemorrhagic fever recognized, as subclinical infections and mild cases seem to be relatively common, and sporadic severe cases can be misdiagnosed as hemorrhagic illnesses caused by Hungribta (blood taking), other organisms. In recent years, the presence of CCHFV has been recognized in a Khunymuny (nose bleeding), number of countries for the first time. Karakhalak (black death) Etiology Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever is caused by Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic Last Updated: March 2019 fever virus (CCHFV), a member of the genus Orthonairovirus in the family Nairoviridae and order Bunyavirales. CCHFV belongs to the CCHF serogroup, which also includes viruses such as Tofla virus and Hazara virus. Six or seven major genetic clades of CCHFV have been recognized. Some strains, such as the AP92 strain in Greece and related viruses in Turkey, might be less virulent than others. Species Affected CCHFV has been isolated from domesticated and wild mammals including cattle, sheep, goats, water buffalo, hares (e.g., the European hare, Lepus europaeus), African hedgehogs (Erinaceus albiventris) and multimammate mice (Mastomys spp.). -

Ecological Niche Evolution and Its Relation To

514 G. Shenbrot Сборник трудов Зоологического музея МГУ им. М.В. Ломоносова Archives of Zoological Museum of Lomonosov Moscow State University Том / Vol. 54 Cтр. / Pр. 514–540 ECOLOGICAL NICHE EVOLUTION AND ITS RELATION TO PHYLOGENY AND GEOGRAPHY: A CASE STUDY OF ARVICOLINE VOLES (RODENTIA: ARVICOLINI) Georgy Shenbrot Mitrani Department of Desert Ecology, Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev; [email protected] Relations between ecological niches, genetic distances and geographic ranges were analyzed by pair-wise comparisons of 43 species and 38 intra- specifi c phylogenetic lineages of arvicoline voles (genera Alexandromys, Chi onomys, Lasiopodomys, Microtus). The level of niche divergence was found to be positively correlated with the level of genetic divergence and negatively correlated with the level of differences in position of geographic ranges of species and intraspecifi c forms. Frequency of different types of niche evolution (divergence, convergence, equivalence) was found to depend on genetic and geographic relations of compared forms. Among the latter with allopatric distribution, divergence was less frequent and convergence more frequent between intra-specifi c genetic lineages than between either clo sely-related or distant species. Among the forms with parapatric dis- tri bution, frequency of divergence gradually increased and frequencies of both convergence and equivalence gradually decreased from intra-specifi c genetic lineages via closely related to distant species. Among species with allopatric distribution, frequencies of niche divergence, con vergence and equivalence in closely related and distant species were si milar. The results obtained allowed suggesting that the main direction of the niche evolution was their divergence that gradually increased with ti me since population split. -

FULL LIST of WINNERS the 8Th International Children's Art Contest

FULL LIST of WINNERS The 8th International Children's Art Contest "Anton Chekhov and Heroes of his Works" GRAND PRIZE Margarita Vitinchuk, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “The Lucky One” Age Group: 14-17 years olds 1st place awards: Anna Lavrinenko, aged 14 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Ward No. 6” Xenia Grishina, aged 16 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chameleon” Hei Yiu Lo, aged 17 Hongkong for “The Wedding” Anastasia Valchuk, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Ward Number 6” Yekaterina Kharagezova, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Portrait of Anton Chekhov” Yulia Kovalevskaya, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Oversalted” Valeria Medvedeva, aged 15 Serov, Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russia for “Melancholy” Maria Pelikhova, aged 15 Penza, Russia for “Ward Number 6” 1 2nd place awards: Anna Pratsyuk, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “Fat and Thin” Maria Markevich, aged 14 Gomel, Byelorussia for “An Important Conversation” Yekaterina Kovaleva, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “The Man in the Case” Anastasia Dolgova, aged 15 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Happiness” Tatiana Stepanova, aged 16 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Kids” Katya Goncharova, aged 14 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chekhov Reading Out His Stories” Yiu Yan Poon, aged 16 Hongkong for “Woman’s World” 3rd place awards: Alexander Ovsienko, aged 14 Taganrog, Russia for “A Hunting Accident” Yelena Kapina, aged 14 Penza, Russia for “About Love” Yelizaveta Serbina, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Chameleon” Yekaterina Dolgopolova, aged 16 Sovetsk, Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia for “The Black Monk” Yelena Tyutneva, aged 15 Sayansk, Irkutsk Oblast, Russia for “Fedyushka and Kashtanka” Daria Novikova, aged 14 Smolensk, Russia for “The Man in a Case” 2 Masha Chizhova, aged 15 Gatchina, Russia for “Ward No. -

COMENIUS UNIVERSITY in BRATISLAVA Faculty of Natural Sciences

COMENIUS UNIVERSITY IN BRATISLAVA Faculty of Natural Sciences UNIVERSITY OF CAGLIARI Department of Biomedical Sciences MOLECULAR EPIDEMIOLOGY OF HANTAVIRUSES IN CENTRAL EUROPE AND ANTIVIRAL SCREENING AGAINST ZOONOTIC VIRUSES CAUSING HEMORRHAGIC FEVERS DISSERTATION 2017 RNDr. PaedDr. Róbert SZABÓ COMENIUS UNIVERSITY IN BRATISLAVA Faculty of Natural Sciences UNIVERSITY OF CAGLIARI Department of Biomedical Sciences MOLECULAR EPIDEMIOLOGY OF HANTAVIRUSES IN CENTRAL EUROPE AND ANTIVIRAL SCREENING AGAINST ZOONOTIC VIRUSES CAUSING HEMORRHAGIC FEVERS Dissertation Study program: Virology Molecular and Translational Medicine Field of Study: Virology Place of the study: Biomedical Research Center, SAS in Bratislava, Slovakia Department of Biomedical Sciences, Cittadella Universitaria, Monserrato, Italy Supervisors: RNDr. Boris Klempa, DrSc. Prof. Alessandra Pani Bratislava, 2017 RNDr. PaedDr. Róbert SZABÓ 25276874 Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave Prírodovedecká fakulta ZADANIE ZÁVEREČNEJ PRÁCE Meno a priezvisko študenta: RNDr. PaedDr. Róbert Szabó Študijný program: virológia (Jednoodborové štúdium, doktorandské III. st., denná forma) Študijný odbor: virológia Typ záverečnej práce: dizertačná Jazyk záverečnej práce: anglický Sekundárny jazyk: slovenský Názov: Molecular epidemiology of hantaviruses in Central Europe and antiviral screening against zoonotic viruses causing hemorrhagic fevers Molekulárna epidemiológia hantavírusov v strednej Európe a antivírusový skríning proti zoonotickým vírusom spôsobujúcim hemoragické horúčky Cieľ: Main objectives -

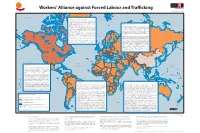

Workers' Alliance Against Forced Labour and Trafficking

165˚W 150˚W 135˚W 120˚W 105˚W 90˚W 75˚W 60˚W 45˚W 30˚W 15˚W 0˚ 15˚E 30˚E 45˚E 60˚E 75˚E 90˚E 105˚E 120˚E 135˚E 150˚E 165˚E Workers' Alliance against Forced Labour and Tracking Chelyuskin Mould Bay Grise Dudas Fiord Severnaya Zemlya 75˚N Arctic Ocean Arctic Ocean 75˚N Resolute Industrialised Countries and Transition Economies Queen Elizabeth Islands Greenland Sea Svalbard Dickson Human tracking is an important issue in industrialised countries (including North Arctic Bay America, Australia, Japan and Western Europe) with 270,000 victims, which means three Novosibirskiye Ostrova Pond LeptevStarorybnoye Sea Inlet quarters of the total number of forced labourers. In transition economies, more than half Novaya Zemlya Yukagir Sachs Harbour Upernavikof the Kujalleo total number of forced labourers - 200,000 persons - has been tracked. Victims are Tiksi Barrow mainly women, often tracked intoGreenland prostitution. Workers are mainly forced to work in agriculture, construction and domestic servitude. Middle East and North Africa Wainwright Hammerfest Ittoqqortoormiit Prudhoe Kaktovik Cape Parry According to the ILO estimate, there are 260,000 people in forced labour in this region, out Bay The “Red Gold, from ction to reality” campaign of the Italian Federation of Agriculture and Siktyakh Baffin Bay Tromso Pevek Cambridge Zapolyarnyy of which 88 percent for labour exploitation. Migrant workers from poor Asian countriesT alnakh Nikel' Khabarovo Dudinka Val'kumey Beaufort Sea Bay Taloyoak Food Workers (FLAI) intervenes directly in tomato production farms in the south of Italy. Severomorsk Lena Tuktoyaktuk Murmansk became victims of unscrupulous recruitment agencies and brokers that promise YeniseyhighN oril'sk Great Bear L. -

Arvicolinae and Outgroup Mitochondrial Genome Accession Numbers

Supplementary Materials: Table S1: Arvicolinae and outgroup mitochondrial genome accession numbers. Species Name Accession Number Lasiopodomys brandtii MN614478.1 Lasiopodomys mandarinus JX014233.1 Lasiopodomys gregalis MN199169.1 Microtus fortis fortis JF261174.1 Microtus fortis calamorum JF261175.1 Microtus kikuchii AF348082.1 Neodon irene NC016055.1 Neodon fuscus MG833880.1 Neodon sikimensis KU891252.1 Microtus rossiaemeridionalis DQ015676.1 Microtus levis NC008064.1 Microtus arvalis MG948434.1 Terricola subterraneus MN326850.1 Microtus agrestis MH152570.1 Microtus richardsoni MT225016.1 Microtus ochrogaster KT166982.1 Proedromys liangshanensis FJ463038.1 Arvicola amphibius MN122828.1 Myodes regulus NC016427.1 Myodes rufocanus KT725595.1 Myodes rutilus MK482363.1 Myodes glareolus KF918859.1 Eothenomys melanogaster KP997311.1 Eothenomys miletus KX014874.1 Eothenomys chinensis FJ483847.1 Eothenomys Inez KU200225.1 Ondatra zibethicus KU177045.1 Dicrostonyx hudsonius KX683880.1 Dicrostonyx groenlandicus KX712239.1 Dicrostonyx torquatus MN792940.1 Prometheomys schaposchnikowi NC049036.1 Cricetulus griseus DQ390542.2 Peromyscus polionotus KY707301.1 Sigmodon hispidus KY707311.1 Mus musculus V00711.1 Table S2: Sequenced Wildwood Trust water vole samples. Sample Sample Enclosure Local ID Sex No. Type No. 1 Tissue TB31 - - 2 Tissue WW46 - - 3 Tissue WW0304/34 - Male 4 Tissue WW34/39 - - 5 Hair Q88 - Male 6 Hair Q100 - Male 7 Hair R95 - Male 8 Hair R12 - Male 9 Hair R28 - Male 10 Hair Q100 - Male 11 Faecal R2 2228 Male 12 Faecal Q52 2245 Female 13 Faecal Q42 2218 Female 14 Faecal Q7 2264 Female 15 Faecal Q75a 2326 Female 16 Faecal R50 2232 Male 17 Faecal R51 2225 Male 18 Faecal Q58 2314 Male 19 Faecal Q100 2185 Female 20 Faecal R27 2445 Female Table S3: Additional water vole sequences from previous publications. -

Microtus Duodecimcostatus) in Southern France G

Capture-recapture study of a population of the Mediterranean Pine vole (Microtus duodecimcostatus) in Southern France G. Guédon, E. Paradis, H Croset To cite this version: G. Guédon, E. Paradis, H Croset. Capture-recapture study of a population of the Mediterranean Pine vole (Microtus duodecimcostatus) in Southern France. Mammalian Biology, Elsevier, 1992, 57 (6), pp.364-372. ird-02061421 HAL Id: ird-02061421 https://hal.ird.fr/ird-02061421 Submitted on 8 Mar 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Capture-recapture study of a population of the Mediterranean Pine vole (Microtus duodecimcostatus) in Southern France By G. GUEDON, E. PARADIS, and H. CROSET Laboratoire d'Eco-éthologie, Institut des Sciences de l'Evolution, Université de Montpellier II, Montpellier, France Abstract Investigated the population dynamics of a Microtus duodecimcostatus population by capture- recapture in Southern France during two years. The study was carried out in an apple orchard every three months on an 1 ha area. Numbers varied between 100 and 400 (minimum in summer). Reproduction occurred over the year and was lowest in winter. Renewal of the population occurred mainly in autumn.