The New Tobacco Products Directive – Potential Economic Impact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Packaging of Dairy Products PACKAGING of DAIRY PRODUCTS

Packaging of Dairy Products PACKAGING OF DAIRY PRODUCTS Author H.G. Patel & Hiral Modha Department of Dairy Technology AAU, Anand M. Ranganadham Department of Dairy Technology SVVU, Tirupati Index Lecture Page No Module 1: Introduction and History of Packaging Development Lesson1. History of Package Development 5-10 Lesson 2. Importance of packaging 11-20 Module 2: Packaging Materials Lesson 3. Selection of Packaging Materials 21-23 Lesson 4. Characteristics of Paper, corrugated paper, fiber 24-30 board and wood Lesson 5. Characteristics of Glass 31-34 Lesson 6. Characteristics of Metals and Metallic 35-41 Containers Lesson 7. Characteristics of Plastics 42-47 Lesson 8. Sources of different plastic materials and 48-58 process of manufacture Lesson 9. Forms of different plastic materials - 1 59-70 Lesson 10. Forms of different plastic material-2 71-78 Lesson 11. Forms of different plastic materials – 3 79-85 Lesson 12. Newer forms with combination of two or more 86-96 ingredients Lesson 13. Foils and Laminates – Characteristics and 97-101 Importance in Food Industry Lesson 14. Characteristics of Retort Pouches 102-104 Module 3: Package Forms Lesson 15. Forms of packages used for packaging of food 105-130 and dairy products Module 4: Legal Requirement Lesson 16. Safety requirements of packaging materials 131-139 and product information Module 5: Packaging of Milk And milk Products Lesson 17. Pasteurized Milk 140-144 Lesson 18. UHT-Sterilized milk 145-147 Lesson 19. Aseptic packaging 148-151 Lesson 20. Fat Rich Dairy Products - Butter and Ghee 152-156 Lesson 21. Coagulated and Desiccated Indigenous Dairy 157-162 Products and their Sweetmeats Lesson 22. -

DANA DAIRY GROUP DANA Full Cream UHT Milk BOTTLE with Cap

DANA DAIRY GROUP DANA Full Cream UHT Milk BOTTLE with cap Product: DANA Full Cream UHT Milk BOTTLE with cap UHT 3.5% Fat Origin: FRANCE Shelf Life: 30 day Carton: 1 Liter | 2x 6x 1 L / Carton (12x1L per Carton) Carton: 0.5 Liter | 2x 6x 0.5 L / Carton Carton: 0.25 Liter | 2x 24x 0.25 L / Carton (48pcs per carton) Packaging type: UHT 1 L Container Loading: 16,680 liters / 20‘ FCL Container Loading: 21,360 liters / 40‘ FCL Packaging type: UHT 500ML Container Loading: 30,000 items / 20‘ FCL Container Loading: 47,460 items / 40‘ FCL Packaging type: UHT 250ML Container Loading: 55,296 items / 20‘ FCL Container Loading: 90,000 items / 40‘ FCL [email protected] facebook.com/danadairygroup1 twitter.com/DanaDairy www.danadairy.com DANA Semi Skimmed UHT Milk BOTTLE with cap Product: DANA Semi Skimmed UHT Milk BOTTLE with cap UHT 1.5% Fat Origin: FRANCE Shelf Life: 300 day Carton: 1 Liter | 2x 6x 1 L / Carton (12x1L per Carton) Carton: 0.5 Liter | 2x 6x 0.5 L / Carton Carton: 0.25 Liter | 2x 24x 0.25 L / Carton (48pcs per carton) Packaging type: UHT 1 L Container Loading: 16,680 liters / 20‘ FCL Container Loading: 21,360 liters / 40‘ FCL Packaging type: UHT 500ML Container Loading: 30,000 items / 20‘ FCL Container Loading: 47,460 items / 40‘ FCL Packaging type: UHT 250ML Container Loading: 55,296 items / 20‘ FCL Container Loading: 90,000 items / 40‘ FCL [email protected] facebook.com/danadairygroup1 twitter.com/DanaDairy www.danadairy.com Evaporated Milk Full Cream Animal Fat Easy Open Product: Evaporated milk (Animal fat) Easy Open 7.5% -

L I T R E a III I N T E L L I G E N T E D I T I O N D E B U

L i t r e a III Intelligent Edition DEBUT! CO.,LTD MFG.,LTD 3-3-1 Meishinguchi Toyonaka,Osaka 561-0841 Japan Tel ; +81-6-7635-6312 Fax ; +81-6-7635-6313 E-mail (International Sales) : [email protected] Yuyama HQ.Website: www.yuyama.co.jp JQA-QM5424 JQA-EM3387 YUYAMA MFG. CO.,LTD OKAYAMA FACTORY ISO9001:2008 ISO14001 Compact Fully Automatic Tablet Dispensing Machine Yuyama MFG Co., Ltd has obtained ISO9001 (Year of 2000) on March 2003. It is not only for managing quality control process but also pursuing the 100% Location Free RFID Canister customer satisfaction. In addition, Okayama factory has obtained ISO14001, & which is for environment management Yuyama U.S.A.Website: Universal Canister system, on September 2003. www.yuyamarx.com Versatile Functionality Yuyama's original versatile canister Universal Canister(UC) OPTION ◎Free from Manual-fill saves your time ! Lock and Display prevent from the missetting of medication ◎Error-free guarantees accurate dispensing ! Only when the medication is verified, UC will be released. In addition, LED shows patient name and medication name. UNIVERSAL CANISTER Simple and Speedy Easy to handle. Just dump the medications in, UC will automatically dispense in accordance with the prescription. One UC can process various medications ! Flexibility increases efficiency ! Just put medications into UC then it's ready ! Preventing Dispensing from a dispensing error, increasing the safety. LED displays Scan the barcode, Dump the Set the UC the medication. then UC will pop out. medications in. Check medications remaining in UC Easy cleaning In order to enhance the safety, it is All components touching metication recommended to release UC and are detachable. -

Beer Instructions

1 TM WHAT YOU NEED • 1 KG ABC Crafted Series Dextrose • Fermentation bucket (minimum 25L capacity) • Large mixing paddle • Thermometer or thermometer strip • Syphon Kit • 250 G B-BriteTM Cleaner • ABC Crafted Series Swing Top Bottles *Contained in equipment starter pack CE QUE VOUS AUREZ BESOIN • 1 Kg de ABC Crafted Series Dextrose • Cuve de Fermentation (contenant de 25 lts min.) • Une grande cuillère de brassage (plastique) • Thermomètre • Ensemble de transvidage • 250 G de B-BriteTM Cleaner • Bouteilles avec bouchon basculant GETTING STARTED 1 DÉPART 2 NOTE: Additives are in the 2nd pouch inside the bag Clean and sanitise your Fermentation Bucket, Lid and REMARQUE: les additifs se trouvent dans la deuxième Mixing Paddle with B-Brite following instructions on the pochette à l'intérieur du sac sachet. Make a note of your batch number (found on the back of the pouch) here: Stand the pouch in warm water for 15 minutes to soften the extract. Nettoyer et stériliser votre cuve de Fermentation, le 15 mins couvercle et la cuillère de brassage avec B-Brite en suivant les instructions sur le sachet. Prendre en note Mettre le sac en le numéro deproduction que vous trouverez sur le sac position verticale dans de mélange de malt. #Numéro de l'eau chaude pendant 15 minutes pour ramollir le malt. 3 4 5 Pour the liquid malt Boil 3L of water, add Top up to 23L using LM extract from the DS to bucket. Add 1kg of cold tap water and pouch into your dextrose sugar and stir well. fermentation bucket. stir until dissolved. -

Development of In-Transit Ripening Technology for Delivering

DEVELOPMENT OF IN-TRANSIT RIPENING TECHNOLOGY FOR DELIVERING READY-TO-EAT PEARS By CHENYI XU A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Science Graduate Program in Food Science Written under the direction of Kit L. Yam And approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS DEVELOPMENT OF IN-TRANSIT RIPENING TECHNOLOGY FOR DELIVERING READY-TO-EAT PEARS By CHENYI XU Thesis Director: Kit L. Yam Non-availability of year-around fully-ripened ready-to-eat pears at retail level has become one of major factors that limit fresh pear consumption in U.S. market in recent years. The objective of this project is to test the feasibility of developing a ripening technology that can have pear fully-ripened when they are delivered to distribution center. Ripening is triggered by ethylene encapsulated in α-cyclodextrin, packaged in sachet and control released by moisture from respiration of pears, under refrigeration temperature during transportation. The objective is composed of three sub-objectives: (1) Ethylene encapsulation in α-cyclodextrin. (2) Release study of sachet (PVA film and Tyvek® paper) packaged encapsulated complex with RH as trigger (70%, 80% and 90%). (3) Biological evaluation ii of efficacy of ethylene released from sachet system. Ethylene encapsulation was controlled by encapsulation duration time and headspace ethylene concentration. Under 1×106 ppm headspace concentration, ethylene was encapsulated in α-cyclodextrin with 2.1% inclusion ratio within 20hrs. Headspace ethylene concentration and duration time did not change inclusion ratio of encapsulated complex, remaining around 2.1%. -

A Tea for Every

our tea offering CATALOGUE FOR CORPORATE SALES a tea for WHITE TEA GREEN TEA ROOIBOS ROOIBOS ORGANIC ORGANIC ORGANIC buddha's blend silk dragon jasmine cinnamon rooibos chai super ginger every mug A zen melange of jasmine Spring-plucked green tea, This combo of cinnamon and This super-spicy rooibos pearls, hibiscus blossoms scented with night-blooming rooibos has a clean taste your is packed with ginger, and white and green tea. jasmine flowers. breath will thank you for. peppercorns and pepper. GREEN TEA OOLONG FRUIT INFUSION FRUIT INFUSION ORGANIC green passionfruit the skinny forever nuts strawberry rhubarb parfait A super refreshing blend of With pu'erh, ginger, eleuthero This nutty jumble of almonds, This rich, tangy blend green tea, pineapple and and oolong, it's the ultimate apples and cinnamon steeps combines rhubarb, strawberry passion fruit. digestive aid. bright pink. It's nuts! and yogurt pieces. BLACK TEA BLACK TEA HERBAL HERBAL ORGANIC ORGANIC ORGANIC ORGANIC cream of earl grey david's breakfast blend mother's little helper peppermint amour A creamy twist on the classic A sweet, full-bodied black Drift away with this relaxing This refreshingly minty Earl Grey, with a rich hint of tea you’ll somehow love even blend of peppermint, herb is super soothing and vanilla bean. more with a splash of milk. lemongrass and valerian root. revitalizing. BLACK TEA MATÉ HERBAL FRUIT INFUSION ORGANIC ORGANIC saigon chai the buzz cold 911 just peachy Black tea with Saigon This stimulating blend of ginger, At the first sign of a cold, This fruity iced tea is packed cinnamon, ginger, cardamom matcha, maté, guarana and citrus reach for this super-soothing with the juicy flavour of ripe and peppercorns. -

Submission: Hobart Single-Use Plastics By-Law

SUBMISSIONS FROM THE NATIONAL RETAIL ASSOCIATION In response to: Single-use Plastics By-law (By-law and Regulatory Impact Statement) Submitted to: City of Hobart November 2019 Disclaimer and Reproduction Permission To the full extent permitted by law, the National Retail Association: • makes no statements, representations, or warranties about the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the production or its suitability for your purposes, and • disclaims all responsibility and all liability (including, without limitation, liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses, damages and costs you might incur as a result of the information being inaccurate or incomplete in any way, and for any reason. Copyright protects this production and resides with the National Retail Association, Australia. All rights are reserved and no part of this material may be reproduced without the written permission of the National Retail Association. Enquiries: David Stout, Director of Policy P: 0409 926 066 E: [email protected] National Retail Association Submissions on Single-Use Plastics By-Law (Hobart) 2 | 25 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 4 2. ABOUT THE NATIONAL RETAIL ASSOCIATION ...................................................................... 6 3. RETAILER ACTIONS TO DATE ............................................................................................... 7 Voluntary initiatives ................................................................................................................................... -

Innovative Packaging Technologies to Enhance the Safety and the Quality of Fresh Raspberry

INNOVATIVE PACKAGING TECHNOLOGIES TO ENHANCE THE SAFETY AND THE QUALITY OF FRESH RASPBERRY Jeanne S. Peters1, Ariane Vasilatis1, Thomas J. Gianfagna1 and Kit Yam2 Plant Biology Department, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901; 2Food Science Department, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 Abstract The goal of this project is to develop innovative packaging systems for fresh raspberry and other Results fruit to enhance quality and safety, and to extend Raspberries held in shelf-life for the small grower. We are developing a clamshells fitted with these science-based approach to extend the shelf life of fresh sachets and then sealed with raspberry, and other small fruit using packaging as a MAP lost less weight and delivery system to minimize microbial contamination had less disease as seen in through the controlled release of thyme oil, and to Fig 2. and Table 1 and Table extend shelf life using modified atmosphere 2 packages(MAP). Introduction A The major postharvest pathogen of raspberry is Botrytis cinerea, the causal agent of gray mold disease. Essential oils (EO) from common herbs such as thyme and oregano have been known for centuries to have anti-microbial activity. We incorporated the EO’s into controlled release packaging (CRP) that releases the active compounds at differentiable rates suitable for short-term inhibition of microorganisms in fresh fruits. For our delivery system, we encapsulated the EO’s into cyclodextrin (CD), which stabilizes them, and then we wrap these capsules into a TyvekTM sachet, which can be placed inside the packaging (Fig. 1). CRP can prolong shelf life without overloading the fruit with additives and can continually B replenish the active compounds from the packaging to maintain Fig. -

Apple Cider • Long Spoon Or Paddle a Traditional Hard Sparkling Cider That Is Packed • Instructions Full of Flavor

Recommended Brew Day Equipment Contents • Concentrate • 7.9 Gallon Fermenter • Thermometer with Lid • Yeast Sachet • Cleanser • Hydrometer • Flavor Sachet • No-Rinse Sanitizer • Airlock • Sweetener Sachet Apple Cider • Long Spoon or Paddle A traditional hard sparkling cider that is packed • Instructions full of flavor. This apple cider is crisp, light and • One Gallon or Larger Pot refreshing, a perfect choice any time of the year. OG: 1.041 - 1.043 FG: 1.004 ABV: 5.2% Color: Golden Recommended Procedures Brewing Tips 1Never pour hot liquid into a glass NOTE: Read all recommended procedures before you begin. carboy. BREW DAY (DATE ___/____/___) 2use a good quality drinking water with 1. CLEAN AND SANITIZE this kit. If you are unsure about your water Thoroughly clean and sanitize ALL equipment and utensils that will come in contact with your cider using quality consider using bottled water. a cleanser and a certified sanitizer, e.g., Star San or IO Star. 3If you prefer a sweet cider add the whole 2. BOIL contents of sweetener sachet, for a medi- Bring 1 gallon (128 oz. / 3.78L) of water to a boil. Once the water is boiling dissolve 2 lbs. (.90kg) of corn um-sweet cider add half of the sweetener sugar (not included) into the boiling water then add the mixture to the sanitized fermenter1 (WARNING: sachet, or for a drier cider do not add any of Never pour hot liquid into a glass carboy). Remove the additional ingredients and instructions from the the sweetener sachet. pouch. Next, pour the liquid concentrate from the pouch into the sanitized fermenter which contains the 4 boiled sugar water. -

CN0025 & CN0035 Description When a Campygen Sachet Is Placed in A

CAMPYGEN Code: CN0025 & CN0035 Description When a CampyGen sachet is placed in a sealed jar, the atmospheric oxygen in the jar is rapidly absorbed with the simultaneous generation of carbon dioxide, producing the appropriate microaerobic conditions. This novel method differs from others commonly used in that the reaction proceeds with no evolution of hydro- gen, and therefore, does not require a catalyst. Furthermore, water is not required to activate the reaction. An evaluation which compared CampyGen with the evacuation/replacement method and gas generating envelopes showed CampyGen to be effective. Components Each box contains: 10 CampyGen paper sachets which are individually foil packed. 1 Product Insert The active component within each CampyGen sachet is ascorbic acid. Precautions This product is for in vitro use only As soon as the CampyGen paper sachet is exposed to air, the reaction will start. It is therefore essential that the paper sachet is placed in the jar and the jar sealed within one minute. The reaction of the ascorbic acid with oxygen is exothermic. However, the temperature of the CampyGen paper sachet will not exceed 65°C. Storage Store at 2-25°C. Under these conditions, the CampyGen sachets will retain their reactivity until the expiry date given on the outer box and on the foil sachet. Directions CN0025 is designed for use in 2.5 litre jars including the new Oxoid AnaeroJar. CN0035 is designed for use in 3.5 litre jars. 1 Place the inoculated media plates in the appropriate jar. Disposable plastic Petri dishes should be of the vented variety to aid gas transfer between the interior and exterior of the plates. -

Celebrating Over 30 Years of Service

CELEBRATING OVER 30 YEARS OF SERVICE ParksCoffee.com | 800.889.7827 PARKS COFFEE | Office Refreshment Professionals Parks Coffee Office Refreshment Professionals Since 1986 Our Service Area We currently service 20,000 corporate accounts in the DFW Metroplex, Houston, San Antonio, Waco, Austin, Midland, Odessa, Oklahoma City, Tulsa, Phoenix, Tucson, Los Angeles, and Shreveport areas. Our client’s count on our more than 250 friendly uniformed route professionals to expertly fill their orders on a weekly basis. And, of course, our GPS monitored delivery vehicles provide the transportation for all the products and services required to give a first rate experience. Our Promise to You Parks Coffee® strives for our customers’ affection. We are the best and most complete Office Coffee Service (OCS) in America; providing a comprehensive array of freshly roasted coffees, snacks, drinks, break room and janitorial supplies. Our friendly and knowledgeable team is committed to serving with skill and problem solving tenacity. We are the refreshment professionals, offering white glove service. The Parks Coffee Menu 02 Our Story Coffee, Tea & Cocoa 13 Parks Coffee® Fraction Packs / Filter Packs 14 Parks Coffee® Whole Bean / Ground Coffee 15 Parks Coffee® Pod Singles / Bigelow Tea Pod Singles 16 Parks Coffee® Single-Cups / Keurig® K-Cup® Packs 18 MARS Drinks® Fresh Packs for FLAVIA® 20 Starbucks® Coffees / National Coffee Brands 21 Espresso Capsules / Liquid Coffees / Hot Chocolate & Cider 22 Parks Iced Teas 23 Tea Bags Cream, Sugar & Condiments 25 Creamer / Sweetener / Condiments Cold Beverage Options 26 Soft Drinks 28 Juice / Milk / Sports Drinks / Energy Drinks 29 Crystal Light® / Bottled Water / Enhanced Water Snacks & Food 30 Snacks 31 Soups / Quick Fixes 32 Snack Bars / Cookies & Baked Goods 33 Frozen Cookie Dough / Gum & Mints / Candy Janitorial & Break Room Supplies 34 Cups / Lids 35 Plates / Bowls / Utensils 36 Paper Goods 37 First Aid / Antiviral Protection / Break Room Supplies 38 Brewing Equipment Give us a Buzz. -

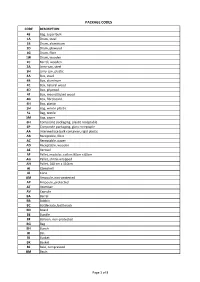

Package Codes

PACKAGE CODES CODE DESCRIPTION 43 Bag, super bulk 1A Drum, steel 1B Drum, aluminium 1D Drum, plywood 1G Drum, fibre 1W Drum, wooden 2C Barrel, wooden 3A Jerry-can, steel 3H Jerry-can, plastic 4A Box, steel 4B Box, aluminum 4C Box, natural wood 4D Box, plywood 4F Box, reconstituted wood 4G Box, fibreboard 4H Box, plastic 5H Bag, woven plastic 5L Bag, textile 5M Bag, paper 6H ComposIte packaging, plastic receptable 6P Composite packaging, glass receptaple AA Intermediate bulk container, rigid plastic AB Receptable, fibre AC Receptable, paper AD Receptable, wooden AE Aerosol AF Pallet, modular, collars 80cm x 60cm AG Pallet, shrink-wrapped AH Pallet, 100 cm x 110cm AI Clamshell AJ Cone AM Ampoule, non-protected AP Ampoule, protected AT Atomiser AV Capsule BA Barrel BB Bobbin BC Bottlecrate, bottlerack BD Board BE Bundle BF Balloon, non-protected BG Bag BH Bunch BI Bin BJ Bucket BK Basket BL Bale, compressed BM Basin Page 1 of 8 PACKAGE CODES CODE DESCRIPTION BN Bale, non-compressed BO Bottle, non-protected, cylindrical BP Balloon, protected BQ Bottle, protected cylindrical BR Bar BS Bottle, non-protected, bulbous BT Bolt BU Butt BV Bottle, protected bulbous BW Box, for liquids BX Box BY Board, in bundle/bunch/truss, BZ Bars, in bundle/bunch/truss CA Can, rectangular CB Beer crate CC Churn CD Can, with handle and spout CE Creel CF Coffer CG Cage CH Chest CI Canister CJ Coffin CK Cask CL Coil CM Collis CN Container not otherwise specified as transport equipment CO Carboy, non-protected CP Carboy, protected CQ Cartdidge CR Crate CS Case CT