Download This Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Can Hear Music

5 I CAN HEAR MUSIC 1969–1970 “Aquarius,” “Let the Sunshine In” » The 5th Dimension “Crimson and Clover” » Tommy James and the Shondells “Get Back,” “Come Together” » The Beatles “Honky Tonk Women” » Rolling Stones “Everyday People” » Sly and the Family Stone “Proud Mary,” “Born on the Bayou,” “Bad Moon Rising,” “Green River,” “Traveling Band” » Creedence Clearwater Revival “In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida” » Iron Butterfly “Mama Told Me Not to Come” » Three Dog Night “All Right Now” » Free “Evil Ways” » Santanaproof “Ride Captain Ride” » Blues Image Songs! The entire Gainesville music scene was built around songs: Top Forty songs on the radio, songs on albums, original songs performed on stage by bands and other musical ensembles. The late sixties was a golden age of rock and pop music and the rise of the rock band as a musical entity. As the counterculture marched for equal rights and against the war in Vietnam, a sonic revolution was occurring in the recording studio and on the concert stage. New sounds were being created through multitrack recording techniques, and record producers such as Phil Spector and George Martin became integral parts of the creative process. Musicians expanded their sonic palette by experimenting with the sounds of sitar, and through sound-modifying electronic ef- fects such as the wah-wah pedal, fuzz tone, and the Echoplex tape-de- lay unit, as well as a variety of new electronic keyboard instruments and synthesizers. The sound of every musical instrument contributed toward the overall sound of a performance or recording, and bands were begin- ning to expand beyond the core of drums, bass, and a couple guitars. -

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

Razorcake Issue #09

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 www.razorcake.com #9 know I’m supposed to be jaded. I’ve been hanging around girl found out that the show we’d booked in her town was in a punk rock for so long. I’ve seen so many shows. I’ve bar and she and her friends couldn’t get in, she set up a IIwatched so many bands and fads and zines and people second, all-ages show for us in her town. In fact, everywhere come and go. I’m now at that point in my life where a lot of I went, people were taking matters into their own hands. They kids at all-ages shows really are half my age. By all rights, were setting up independent bookstores and info shops and art it’s time for me to start acting like a grumpy old man, declare galleries and zine libraries and makeshift venues. Every town punk rock dead, and start whining about how bands today are I went to inspired me a little more. just second-rate knock-offs of the bands that I grew up loving. hen, I thought about all these books about punk rock Hell, I should be writing stories about “back in the day” for that have been coming out lately, and about all the jaded Spin by now. But, somehow, the requisite feelings of being TTold guys talking about how things were more vital back jaded are eluding me. In fact, I’m downright optimistic. in the day. But I remember a lot of those days and that “How can this be?” you ask. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

To Students Is Revealed

r . - - MSC Choir Slates Candlelight Concert THE # APER . Vol.. 44 Millersville State College , Millersville , Pa.#. December 8 , 1971 No.. 15 -- Financial Aid Available . To Students Is Revealed - In the past few issues of cerned with each of these pro 499 ; 28 students $7,500$ , to $8-$ ,- ' - - students SNAPPERSNAPPER , several articles have grams may aid in gaining a bet 999, and 10 students $9,000$ , to tIIIV VIII students- . - g been printed about the various ter perspective about the types $10,000.$ , One hundred twenty- , I P II II' , ¬ . ' types of aid available to stustu-- of available aid. ifiveve students are receiving this ' l ! I' ; dents.. Types of aid discussed In the fall , 1971 semester , 1-,- type of aid this fall including ' ' ' II ill I ' i I'I , dV have included the PHEAA state 297 MSC students 38 . i received black students. scholarships , National De-¬ I the De- PHEAA scholarships.. These In the College Work Study fense Student Loan , the College scholarships amounted to $292-$ ,- program , the figures are as folfol--¬ Work Study Program and the 660 in aid.. In addition , 496 peo- lows : ( number of students rere--¬ Educational Opportunities Grant ple were denied scholarships for ceiving aid is listed followed by Program.. not meeting eligibility guide- family income ) , 14 students , - - Some facts and figures con lines set by the PHEAA.. $$0 to $2,999$ , ; 36 students $3,000$ , ll IiII - ¬ students The of , ; , Ipl number people receiv- to $5,999$ 30 students -$6,000$ III students ! ; tI ing aid and the family income to $7,499$ , 27 students $$7,500, II lll I - I I Operations Board students - ; Il of each are as follows : 54 stu to $8,999$ , 45 students $9,000$ , to l i students- dents-$0$ to 2,999, ; 166 students $11,999$ , , and 30 students-over Sponsors ; - Contest -$3,000$ , to $5,999$ , 153 students $12,000.$ , . -

Smash Hits Volume 34

\ ^^9^^ 30p FORTNlGHTiy March 20-Aprii 2 1980 Words t0^ TOPr includi Ator-* Hap House €oir Underground to GAR! SKias in coioui GfiRR/£V£f/ mjlt< H/Kim TEEIM THAT TU/W imv UGCfMONSTERS/ J /f yO(/ WOULD LIKE A FREE COLOUR POSTER COPY OF THIS ADVERTISEMENT, FILL IN THE COUPON AND RETURN IT TO: HULK POSTER, PO BOXt, SUDBURY, SUFFOLK C010 6SL. I AGE (PLEASE TICK THE APPROPRIATE SOX) UNDER 13[JI3-f7\JlS AND OVER U OFFER CLOSES ON APRIL 30TH 1980 ALLOW 28 DAYS FOR DELIVERY (swcKCAmisMASi) I I I iNAME ADDRESS.. SHt ' -*^' L.-**^ ¥• Mar 20-April 2 1980 Vol 2 No. 6 ECHO BEACH Martha Muffins 4 First of all, a big hi to all new &The readers of Smash Hits, and ANOTHER NAIL IN MY HEART welcome to the magazine that Squeeze 4 brings your vinyl alive! A warm welcome back too to all our much GOING UNDERGROUND loved regular readers. In addition The Jam 5 to all your usual news, features and chart songwords, we've got ATOMIC some extras for you — your free Blondie 6 record, a mini-P/ as crossword prize — as well as an extra song HELLO I AM YOUR HEART and revamping our Bette Bright 13 reviews/opinion section. We've also got a brand new regular ROSIE feature starting this issue — Joan Armatrading 13 regular coverage of the independent label scene (on page Managing Editor KOOL IN THE KAFTAN Nick Logan 26) plus the results of the Smash B. A. Robertson 16 Hits Readers Poll which are on Editor pages 1 4 and 1 5. -

Heroes Magazine

HEROES ISSUE #01 Radrennbahn Weissensee a year later. The title of triumphant, words the song is a reference to the 1975 track “Hero” by and music. Producer Tony Visconti took credit for the German band Neu!, whom Bowie and Eno inspiring the image of the lovers kissing “by the admired. It was one of the early tracks recorded wall”, when he and backing vocalist Antonia Maass BOWIE during the album sessions, but remained (Maaß) embraced in front of Bowie as he looked an instrumental until towards the out of the Hansa Studio window. Bowie’s habit in end of production. The quotation the period following the song’s release was to say marks in the title of the song, a that the protagonists were based on an anonymous “’Heroes’” is a song written deliberate affectation, were young couple but Visconti, who was married to by David Bowie and Brian Eno in 1977. designed to impart an Mary Hopkin at the time, contends that Bowie was Produced by Bowie and Tony Visconti, it ironic quality on the protecting him and his affair with Maass. Bowie was released both as a single and as the otherwise highly confirmed this in 2003. title track of the album “Heroes”. A product romantic, even The music, co-written by Bowie and Eno, has of Bowie’s “Berlin” period, and not a huge hit in been likened to a Wall of Sound production, an the UK or US at the time, the song has gone on undulating juggernaut of guitars, percussion and to become one of Bowie’s signature songs and is synthesizers. -

The Rolling Stones and Performance of Authenticity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies Art & Visual Studies 2017 FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY Mariia Spirina University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.135 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Spirina, Mariia, "FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/art_etds/13 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art & Visual Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

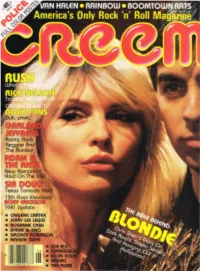

RUSH: but WHY ARE THEY in SUCH a HURRY? What to Do When the Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•

• CARLENE CARTER • JERRY LEE LEWIS • ROSANNE CASH • BYRNE & ENO • SMOKEY acMlNSON • MARVIN GAYE THE SONG OF INJUN ADAM Or What's A Picnic Without Ants? .•.•.•••••..•.•.••..•••••.••.•••..••••••.•••••.•••.•••••. 18 tight music by brit people by Chris Salewicz WHAT YEAR DID YOU SAY THIS WAS? Hippie Happiness From Sir Doug ....••..•..••..•.••••••••.•.••••••••••••.••••..•...•.••.. 20 tequila feeler by Toby Goldstein BIG CLAY PIGEONS WITH A MIND OF THEIR OWN The CREEM Guide To Rock Fans ••.•••••••••••••••••••.•.••.•••••••.••••.•..•.•••••••••. 22 nebulous manhood displayed by Rick Johnson HOUDINI IN DREADLOCKS . Garland Jeffreys' Newest Slight-Of-Sound •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.••..••. 24 no 'fro pick. no cry by Toby Goldstein BLONDIE IN L.A. And Now For Something Different ••••.••..•.••.••.•.•••..••••••••••.••••.••••••.••..••••• 25 actual wri ting by Blondie's Chris Stein THE PSYCHEDELIC SOUNDS OF ROKY EmCKSON , A Cold Night For Elevators •••.••.•••••.•••••••••.••••••••.••.••.•••..••.••.•.•.••.•••.••.••. 30 fangs for the memo ries by Gregg Turner RUSH: BUT WHY ARE THEY IN SUCH A HURRY? What To Do When The Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•. 32 mortgage payments mailed out by J . Kordosh POLICE POSTER & CALENDAR •••.•••.•..••••••••••..•••.••.••••••.•••.•.••.••.••.••..•. 34 LONESOME TOWN CHEERS UP Rick Nelson Goes Back On The Boards .•••.••••••..•••••••.••.•••••••••.••.••••••.•.•.. 42 extremely enthusiastic obsewations by Susan Whitall UNSUNG HEROES OF ROCK 'N' ROLL: ELLA MAE MORSE .••.••••.•..•••.••.• 48 control -

Williams, Justin A. (2010) Musical Borrowing in Hip-Hop Music: Theoretical Frameworks and Case Studies

Williams, Justin A. (2010) Musical borrowing in hip-hop music: theoretical frameworks and case studies. PhD thesis, University of Nottingham. Access from the University of Nottingham repository: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/11081/1/JustinWilliams_PhDfinal.pdf Copyright and reuse: The Nottingham ePrints service makes this work by researchers of the University of Nottingham available open access under the following conditions. · Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. · To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in Nottingham ePrints has been checked for eligibility before being made available. · Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not- for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. · Quotations or similar reproductions must be sufficiently acknowledged. Please see our full end user licence at: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/end_user_agreement.pdf A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the repository url above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information, please contact [email protected] MUSICAL BORROWING IN HIP-HOP MUSIC: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS AND CASE STUDIES Justin A. -

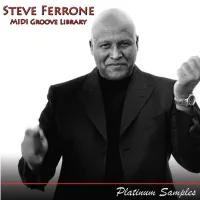

Steve Ferrone MIDI Groove Library Manual.Pdf

Steve Ferrone MIDI Groove Library Welcome and thank you for purchasing the Platinum Samples Steve Ferrone MIDI Groove Library. This groove library is available in multiple formats: BFD2, BFD Eco, BFD Eco DV, Toontrack EZDrummer & Superior Drummer, Addictive Drums, Cakewalk Session Drummer and General MIDI. Please download the version(s) you will be using. BFD2, BFD Eco & BFD Eco DV Installation: Windows XP or later The BFD library download is provided as a single compressed (zipped) archive. The archive is named Steve_Ferrone_BFD.zip 1. In order to access the installer, right-click the downloaded archive package and select “Extract All...” to unarchive. Find the installer named Steve Ferrone Groove Library Installer WIN.exe and double click it to run it. 2. A splash screen appears, followed by a welcome page. Read the on-screen instructions and click Next to begin the installation. 3. Read the license conditions and check the tick box to agree. If you leave the tick box unchecked, you will not be able to continue with the installation. Click Next to proceed. 4. Specify any folder on a suitable hard disk in which to install the groove library data. Note: If installing on Windows Vista®, the current BFD Eco and BFD2 data paths may not be listed. In this case you must browse to the required data path manually. The drop-down menu contains all current BFD Eco, BFD Eco DV or BFD2 data paths. Select one of these or click Browse to navigate to and select a new location. If you select a new location, it is added to BFD Eco’s and/or BFD2’s and BFD Eco DV’s list of data paths automatically. -

"Weird Al" Yankovic

"Weird Al" Yankovic - Ebay Abba - Take A Chance On Me `M` - Pop Muzik Abba - The Name Of The Game 10cc - The Things We Do For Love Abba - The Winner Takes It All 10cc - Wall Street Shuffle Abba - Waterloo 1927 - Compulsory Hero ABC - Poison Arrow 1927 - If I Could ABC - When Smokey Sings 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings And Queens Ac Dc - Long Way To The Top 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings And Queens Ac Dc - Thunderstruck 30h!3 - Don't Trust Me Ac Dc - You Shook Me All Night Long 3Oh!3 feat. Katy Perry - Starstrukk AC/DC - Rocker 5 Star - Rain Or Shine Ac/dc - Back In Black 50 Cent - Candy Shop AC/DC - For Those About To Rock 50 Cent - Just A Lil' Bit AC/DC - Heatseeker A.R. Rahman Feat. The Pussycat Dolls - Jai Ho! (You AC/DC - Hell's Bells Are My Destiny) AC/DC - Let There Be Rock Aaliyah - Try Again AC/DC - Thunderstruck Abba - Chiquitita AC-DC - It's A Long Way To The Top Abba - Dancing Queen Adam Faith - The Time Has Come Abba - Does Your Mother Know Adamski - Killer Abba - Fernando Adrian Zmed (Grease 2) - Prowlin' Abba - Gimme Gimme Gimme (A Man After Midnight) Adventures Of Stevie V - Dirty Cash Abba - Knowing Me, Knowing You Aerosmith - Dude (Looks Like A Lady) Abba - Mamma Mia Aerosmith - Love In An Elevator Abba - Super Trouper Aerosmith - Sweet Emotion A-Ha - Cry Wolf Alanis Morissette - Not The Doctor A-Ha - Touchy Alanis Morissette - You Oughta Know A-Ha - Hunting High & Low Alanis Morrisette - I see Right Through You A-Ha - The Sun Always Shines On TV Alarm - 68 Guns Air Supply - All Out Of Love Albert Hammond - Free Electric Band