Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phillip Street Theatre

COLLECTION FINDING AID Phillip Street Theatre Performing Arts Programs and Ephemera (PROMPT) Australian ColleCtion Development The Phillip Street Theatre (sucCeeded by the Phillip Theatre) was a popular and influential commercial Sydney theatre and theatriCal Company of the 1950s and 1960s that beCame well known for its intimate satiriCal revue produCtions. William Orr was the Company’s founding DireCtor of ProduCtions, and EriC DuCkworth was General Manager. After taking over the MerCury Theatre in Phillip Street, William Orr re- opened it as the Phillip Street Theatre in 1954, presenting a series of “Phillip Street Revues” and children's musicals, including Top of the Bill and Hit and Run (both 1954), Willow Pattern Plate (1957), Cross Section (1957-58), Ride on a Broomstick (1959), Mistress Money (1960). These featured many noted Australian performers, many who later went on to beCome well known film, theatre and television personalities, inCluding Gordon Chater, Margot Lee, Barry Creyton, Jill Perryman, Noeline Brown, Robina Beard, Judi Farr, Kevin Miles, Charles "Bud" Tingwell, Ray Barrett, Ruth CraCknell, June Salter, John Meillon, Barry Humphries, Reg Livermore, Peter Phelps, and Gloria Dawn. The Phillip Street Theatre was demolished at the time of Out on a Limb with Bobby Limb and Dawn Lake in 1961, and the Company moved to the Australian Hall at 150 Elizabeth Street, near Liverpool Street. The Company's name was then shortened to the Phillip Theatre in reCognition of this move. Content Printed materials in the PROMPT ColleCtion include programs and printed ephemera such as broChures, leaflets, tiCkets, etC. Theatre programs are taken as the prime doCumentary evidenCe of a performanCe at the Phillip Street Theatre. -

Australian Theatre Archive

Australian Theatre Archive Barry Creyton b. 1939 Barry Creyton is an actor, writer, director and composer who has succeeded as a theatre maker on three continents. He was a much adored television personality early in his career in Australia, when he was catapulted to stardom as part of the satirical television phenomenon that was The Mavis Bramston Show . Soon afterwards he hosted his own variety show. He has written three highly successful stage plays and appeared on stage and television throughout his career. Creyton has distinguished himself playing and writing comic roles although he has also played dramatic roles, and in recent years he has focused on adapting and directing classic plays. Barry Creyton is a purist who prefers live performance to television, and cautions against a tendency in directors to ‘do a concept production rather than a production which reflects the value of the play’. He has constantly challenged himself throughout his career. As soon as he achieved national celebrity status in the 1960’s he decided to leave Australia in order to work where nobody knew him, and test himself in a new environment as a working actor. Creyton is based in Los Angeles where he lives in the Hollywood Hills. He ended up in tinsel town by accident in 1991, began working as a scriptwriter, and disliked the city at first dubbing it ‘Purgatory with Palm Trees’, but soon fell in love with its glamorous cinema history, the marvellous and vibrant small live theatres and the absorbing world of entertainment that is the life blood of the city. -

Chapter 3 Research Methodology

Where meaning collapses: a creative exploration of the role of humour and laughter in trauma by SYLVIA ALSTON University of Canberra ACT 2601 A creative thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication at the University of Canberra October 2009 Title of thesis: Where meaning collapses: a creative exploration of the role of humour and laughter in trauma. Title of creative component: A bubblegum forest Research question: Given the frequently stated claims that humour is universally good, what function does humour serve in dealing with pain and how can that be represented in fiction? Sylvia Alston © October 2009 ii ABSTRACT The thesis consists of a full-length novel and an exegesis that examines the ways in which humour can be used to restore the symbolic order and serve as a means of regaining control, thus allowing those involved in the most disturbing, painful and challenging situations to feel less powerless. The research component of the thesis involved critical reading, fieldwork, observations, and personal interviews. The texts examined include works by Michael Billig, Henri Bergson and Julia Kristeva, in particular her reference to the act of laughing at the abject as a kind of horrified ‘apocalyptic laughter’, a compulsion to confront that which repels (Kristeva 1982, pp. 204-206). As part of the fieldwork, I completed training to become a Laughter Club leader. Laughter Clubs are based on the notion that laughter, even fake laughter, is beneficial. This concept is explored in more detail in the exegesis. The fieldwork also included training in laughter-generating activities for students and staff at two local primary schools. -

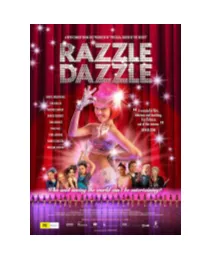

Razzle-Dazzle-Press-Kit.Pdf

Who said saving the world can’t be entertaining? MEDIA KIT In Cinemas: 15 March 2007 OFLC Rating: PG Running Time: 92 Minutes Publicity Catherine Lavelle 0413 88 55 95 [email protected] www.razzledazzlethemovie.com SHORT SYNOPSIS A spectacular comedy about changing the world step-by-step starring Kerry Armstrong, Ben Miller, Nadine Garner, Denise Roberts, Tara Morice, Jane Hall, Toni Lamond, Barry Crocker and Noeline Browne - Razzle Dazzle lifts the curtain on the world of children’s competitive dance. The film follows the eager members of "Mr Jonathon's Dance Academy" who, with their unique dance routines, compete for Grand Final success at Australia's most prestigious competition. Amidst parental politics, petty rivalry, creative controversy and the hysterics of pushy stage mothers, the film takes you behind the glamour and the glitter to a world where, sometimes, winning is everything! “A wonderful film, hilarious and touching. You’ll dance out of the cinema.” Ben Elton "A well observed, brilliantly performed comedy." Steve Coogan RAZZLE DAZZLE is a Film Finance Corporation Australia presentation in association with the New South Wales Film & Television Office of a Wild Eddie production. International Sales – Celluloid Dreams Australia/New Zealand Distribution – Palace Films 3 LONG SYNOPSIS RAZZLE DAZZLE is the story of one dance school and its quest for Grand Final success at the pinnacle of all dance competitions - The Sanosafe Troupe Spectacular. The dance school is run by Mr Jonathon, a teacher and choreographer who believes that through dance he can educate as well as entertain. When the documentary crew begins shooting, the year is set to be a big one for Mr Jonathon’s Jazzketeers. -

AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY a Series That Profiles Some of the Most Extraordinary Australians of Our Time

STUDY GUIDE AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY A series that profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time Noeline Brown 1938– Actor This program is an episode of Australian Biography Series 10 produced under the National Interest Program of Film Australia. This well-established series profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time. Many have had a major impact on the nation’s cultural, political and social life. All are remarkable and inspiring people who have reached a stage in their lives where they can look back and reflect. Through revealing in-depth interviews, they share their stories— of beginnings and challenges, landmarks and turning points. In so doing, they provide us with an invaluable archival record and a unique perspective on the roads we, as a country, have travelled. Australian Biography: Noeline Brown Director/Producer Rod Freedman Executive Producer Mark Hamlyn Duration 26 minutes Year 2005 Study guide prepared by Darren Smith © NFSA Also in Series 10: Tom Bass, Sir Zelman Cowen, Anne Deveson, Joan Kirner, Max Lake, Noel Tovey A FILM AUSTRALIA NATIONAL INTEREST PROGRAM For more information about Film Australia’s programs, contact: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia Sales and Distribution | PO Box 397 Pyrmont NSW 2009 T +61 2 8202 0144 | F +61 2 8202 0101 E: [email protected] | www.nfsa.gov.au AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY: NOELINE BROWN FILM AUSTRALIA 2 SYNOPSIS performer belongs go towards shaping the character. These conventions are what inspire the player and are what the spectator According to Noeline Brown, the trick to life is happiness. understands. -

ON STAGE the Summer 2009 Newsletter of Vol.10 No.1

ON STAGE The Summer 2009 newsletter of Vol.10 No.1 In the National interest It’s all systems go: Arts Victoria has funded a major upgrade for the National Theatre, giving the St Kilda landmark a well-deserved boost. hanks to timely Arts Victoria funding the teaching and production of opera, the VCA in 1977). The auditorium is used for and support from Arts Minister dance and drama. community and commercial hirers as well as TLynne Kosky, the National Theatre The theatre was renamed—naturally the schools-—and it is income from hiring that in St Kilda is set for a major upgrade. enough—the National. The auditorium was subsidises the activities of the schools and Last year the National submitted an split horizontally so that teaching studios permits rental subsidies for community application to Arts Victoria for support in could be installed in the area formerly groups. funding a series of major upgrades to its occupied by the stalls and cinema stage, and Surprisingly, the National gets no recurrent aging facilities, a project totalling $750 000. a new stage and fly tower were built in front government support for its operations. The main fabric of the theatre is now 88 of the old dress circle, which then became ‘Everyone assumes we get help to run the years old. It opened as a cinema, the Victory, an 800-seat auditorium. It opened in 1974. schools because they include accredited on 18 April 1921. The revamped building has housed the vocational training regulated by the state Seven years later, in response to the National’s schools of drama and dance ever government, as well as international students,’ introduction of ‘talkies’ and competition since (the opera school was subsumed by says general manager Robert Taylor. -

Festival 30000 Lp Series 1961-1989

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS FESTIVAL 30,000 LP SERIES 1961-1989 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER © BIG THREE PUBLICATIONS, OCTOBER 2015 Festival 30,000 LP series FESTIVAL LP LABEL ABBREVIATIONS, 1961 TO 1973 AML, SAML, SML, SAM A&M IL IMPULSE SODL A&M - ODE SINL INFINITY SASL A&M - SUSSEX SITFL INTERFUSION SARL AMARET SIVL INVICTUS ML, SML AMPAR, ABC PARAMOUNT, SIL ISLAND GRAND AWARD KL KOMMOTION SAT, SATAL ATA LL LEEDON AL, SAL ATLANTIC SLHL LEE HAZLEWOOD INTERNATIONAL SAVL AVCO EMBASSY LYL, SLYL, SLY LIBERTY SBNL BANNER DL LINDA LEE BCL, SBCL BARCLAY SML, SMML METROMEDIA BBC BBC PL, SPL MONUMENT SBTL BLUE THUMB MRL MUSHROOM BL BRUNSWICK SPGL PAGE ONE CBYL, SCBYL CARNABY PML, SPML PARAMOUNT SCHL CHART SPFL PENNY FARTHING SCYL CHRYSALIS PJL, SPJL PROJECT 3 MCL CLARION RGL REG GRUNDY NDL, SNDL, SNC COMMAND RL REX SCUL COMMONWEALTH UNITED JL, SJL SCEPTER CML, CML, CMC CONCERT-DISC SKL STAX CL, SCL CORAL NL, SNL SUN DDL, SDDL DAFFODIL QL, SQL SUNSHINE SDJL DJM EL, SEL SPIN ZL, SZL DOT TRL, STRL TOP RANK DML, SDML DU MONDE TAL, STAL TRANSATLANTIC SDRL DURIUM TL, STL 20TH CENTURY-FOX EL EMBER UAL, SUAL, SUL UNITED ARTISTS EC, SEC, EL, SEL EVEREST SVHL VIOLETS HOLIDAY SFYL FANTASY VL VOCALION DL, SDL FESTIVAL SVL VOGUE FC FESTIVAL APL VOX FL, SFL FESTIVAL WA WALLIS GNPL, SGNPL GNP CRESCENDO APC, WC, SWC WESTMINSTER HVL, SHVL HISPAVOX SWWL WHITE WHALE SHWL HOT WAX IRL, SIRL IMPERIAL 2 Festival 30,000 LP series FL 30,001 THE BEST OF THE TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS, VOL. -

Australian Ephemera Collection Finding Aid

AUSTRALIAN EPHEMERA COLLECTION FINDING AID PHILLIP STREET THEATRE PERFORMING ARTS PROGRAMS AND EPHEMERA (PROMPT) PRINTED AUSTRALIANA JANUARY 2015 The Phillip Street Theatre (succeeded by the Phillip Theatre) was a popular and influential commercial Sydney theatre and theatrical company of the 1950s and 1960s that became well known for its intimate satirical revue productions. William Orr was the company’s founding Director of Productions, and Eric Duckworth was General Manager. After taking over the Mercury Theatre in Phillip Street, William Orr re-opened it as the Phillip Street Theatre in 1954, presenting a series of “Phillip Street Revues” and children's musicals, including Top of the Bill and Hit and Run (both 1954), Willow Pattern Plate (1957), Cross Section (1957-58), Ride on a Broomstick (1959), Mistress Money (1960). These featured many noted Australian performers, many who later went on to become well known film, theatre and television personalities, including Gordon Chater, Margot Lee, Barry Creyton, Jill Perryman, Noeline Brown, Robina Beard, Judi Farr, Kevin Miles, Charles "Bud" Tingwell, Ray Barrett, Ruth Cracknell, June Salter, John Meillon, Barry Humphries, Reg Livermore, Peter Phelps, and Gloria Dawn. The Phillip Street Theatre was demolished at the time of Out on a Limb with Bobby Limb and Dawn Lake in 1961, and the Company moved to the Australian Hall at 150 Elizabeth Street, near Liverpool Street. The company's name was then shortened to the Phillip Theatre in recognition of this move. From 1981 the programs show the theatre as Phillip Street Theatre once again. Printed materials in the PROMPT collection include programs and printed ephemera such as brochures, leaflets, tickets, etc.