Population Genetic Structure of an Extremely Logged Tree Species Guaiacum Sanctum L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Antibiotic Therapy of Syphilis Charles T

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Genetics Faculty Publications Genetics 2016 Pre-Antibiotic Therapy of Syphilis Charles T. Ambrose University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/microbio_facpub Part of the Medical Immunology Commons Repository Citation Ambrose, Charles T., "Pre-Antibiotic Therapy of Syphilis" (2016). Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Genetics Faculty Publications. 83. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/microbio_facpub/83 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Genetics at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Genetics Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pre-Antibiotic Therapy of Syphilis Notes/Citation Information Published in NESSA Journal of Infectious Diseases and Immunology, v. 1, issue 1, p. 1-20. © 2016 C.T. Ambrose This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/microbio_facpub/83 Journal of Infectious Diseases and Immunology Volume 1| Issue 1 Review Article Open Access PRE-ANTIBIOTICTHERAPY OF SYPHILIS C.T. Ambrose, M.D1* 1Department of Microbiology, College of Medicine, University of Kentucky *Corresponding author: C.T. Ambrose, M.D, College of Medicine, University of Kentucky Department of Microbiology, E-mail: [email protected] Citation: C.T. -

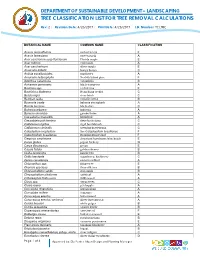

Tree Classification List for Tree Removal Calculations

DEPARTMENT OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT – LANDSCAPING TREE CLASSIFICATION LIST FOR TREE REMOVAL CALCULATIONS Rev: 2 | Revision Date: 4/26/2017 | Print Date: 4/26/2017 I.D. Number: TCLTRC BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME CLASSIFICATION Acacia auriculiformis earleaf acacia F Acacia farnesiana sweet acacia A Acer saccharum susp floridanum Florida maple E Acer rubrum red maple A Acer saccharinum silver maple E Araucaria bidwilli bunya bunya C Ardisia escallonioides marlberry A Araucaria heterophylla Norfolk Island pine F Averrhoa carambola carambola B Avicennia germinans black mangrove A Bauhinia spp. orchid tree E Bauhinia x blakeana Hong Kong orchid C Betula nigra river birch C Bombax ceiba red silk cotton B Bourreria ovata bahama strongbark A Bucida buceras black olive C Bulnesia arborea bulnesia A Bursera simaruba gumbo limbo A Caesalpinia granadillo bridalveil A Caesalpinia pulcherrima dwarf poinciana C Callistemon rigidus rigid bottlebrush C Callistemon viminalis weeping bottlebrush C Calophyllum inophyllum See Calophyullum brasiliense F Calophyullum brasiliense Brazilian Beautyleaf F Carpinus caroliniana American hornbeam; blue beech E Carya glabra pignut hickory D Carya illinoinensis pecan E Cassia fistula golden shower B Ceiba pentandra kapok tree B Celtis laevigata sugarberry; hackberry C Cercis canadensis eastern redbud A Chionanthus spp. fringe tree E Chorisia speciosa floss-silk tree B Chrysophyllum cainito star-apple B Chrysophyllum oliviforme satinleaf A Citharexylum fruticosum fiddlewood A Citrus spp. citrus trees C Clusia rosea pitchapple A Coccoloba diversifolia pigeon plum A Coccoloba uvifera seagrape A Conocarpus erectus buttonwood A Conocarpus erectus ‘sericeus’ silver buttonwood A Cordia bossieri white geiger B Cordia sebestena orange geiger B Cupaniopsis anacardiodes carrotwood F Dalbergia sissoo Indian rosewood E Delonix regia royal poinciana B Diospyros virginiana common persimmon E Eleocarpus decipens Japanese blueberry A Eriobotrya japonica loquat B Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. -

Guaiacum Sanctum: Lignum Vitae1 Edward F

ENH445 Guaiacum sanctum: Lignum Vitae1 Edward F. Gilman, Dennis G. Watson, Ryan W. Klein, Andrew K. Koeser, Deborah R. Hilbert, and Drew C. McLean2 Introduction Uses: tree lawn 3–4 feet wide; tree lawn 4–6 feet wide; tree lawn > 6 ft wide; sidewalk cutout (tree pit); parking lot Lignum vitae is an extremely slow-growing broadleaf island < 100 sq ft; parking lot island 100–200 sq ft; parking evergreen which ultimately reaches 30 feet in height and lot island > 200 sq ft; container or planter; specimen; deck casts light shade, but few people have seen plants of this or patio; Bonsai; highway median size because it is not grown in the trade. Most are seen 8 to 12 feet tall with a beautiful array of multiple trunks and a rounded canopy much like that of a mature crape-myrtle. The one to two-inch-long, leathery, dark green leaves are joined at many times throughout the year by the production of large clusters of bluish purple flowers, the old flowers fading to a light silvery-blue and creating a shimmering haze over the rounded canopy. These flowers are followed by small, heart-shaped, yellow orange berries, appearing on the tree at the same time as the bluish purple flowers and creating a lovely sight. General Information Figure 1. Full Form—Guaiacum sanctum: Lignum vitae Scientific name: Guaiacum sanctum Description Pronunciation: GWY-uh-kum SANK-tum Height: 10 to 30 feet Common name(s): Lignum vitae, holywood, tree of life Spread: 8 to 12 feet Family: Zygophyllaceae Crown uniformity: symmetrical USDA hardiness zones: 10B through 11 (Figure 2) Crown shape: round, vase Origin: native to Florida, the West Indies, Mexico, and Crown density: dense Central America Growth rate: slow UF/IFAS Invasive Assessment Status: native Texture: fine 1. -

Is Guaiacum Sanctum Effective Against Arthritis? an Ethnobotany

Is Guaiacum sanctum Effective Against Arthritis? An Ethnobotany Case by Eric Ribbens, Barbra Burdett, and Angela Green Department of Biological Science Western Illinois University Part I—Anecdotal Evidence Dr. Beth Tonoany is a tropical population ecologist who has been studying an unusual tree, Guaiacum sanctum, which once grew throughout the dry tropical forests of Central America as well as on some of the Caribbean islands. Guaiacum sanctum produces a wood called lignum vitae, and is known in Costa Rica and other Spanish-speaking countries as guayacan reál. The wood is extremely heavy because it contains extensive deposits of resin (Howes, 1949) and it will sink if placed in water (Wilson and Eisner, 1968). During World War I and II it was extensively harvested for use in the ship-building industry because the wood, which does not split easily, is self- lubricating due to its high resin content. The wood is very durable, and was in high demand for constructing bearing sleeves to support ship propellor Figure 1: Seeds of shafts (Scurlock, 1987). It has also been used for making railroad ties Guaiacum sanctum (Woods, 1951). Dr. Tonoany has been studying one of the last remaining populations of lignum vitae in the Palo Verde Nature Preserve in northwestern Costa Rica. Probably fewer than 100 trees remain in Costa Rica, most in the Palo Verde Nature Preserve. Her research has included tracking seedlings and saplings, locating and measuring adult trees, and interviewing some of the local Ticos to learn about the tree’s past history in Costa Rica. The tree, while rare now due to the dramatic conversion of tropical deciduous forest in Costa Rica into pasturelands and to selective logging of the tree for its valuable wood, was once more common, and many of the older Ticos remember that the saplings were used to make cattle switches because of the strong flexible wood in the saplings. -

Landscape Plant List

APPENDIX B-Tree Technical Manual, Download at the "Unified Development Code" from: http://www.cityofedinburg.com/ City of Edinburg Native (Permitted) Plant List e e = P Wildlif s t rac espan: Scientific Name Family Common Name(s) Slow) Medium, Fast, COMMENTS Perennial, A=Annual, D=deciduous Period Blooming Color Bloom Aquatic Soils Moist Riparian Upland Full Shade Shade/Sun Full Sun Att Lif (Bi=Bird Bu=Butterfly(Bi=Bird Be=Bee Height Mature Width Mature Rate Growth ( Spacing Large Trees (Parking lot shade) Acacia wrightii Fabaceae Wright's Acacia X X X Be 30' 20' Medium 20' P, D Spring White Recurved spines; heat & drought tolerant Fast growing shade tree; small fruit is extremely valuable for birds; limbs fairly Celtis laevigata Ulmaceae Sugar Hackberry X X X X X Bi 45' 50' Fast 50' P, D Spring Greenish brittle; drops fine, sticky sap, which is messy Fragrant, showy clusters of small, white flowers produce large quantities of fruit Ehretia anacua Boraginaceae Anacua X X X Bi 45' 50' Slow 50' P, D Jun-Oct White valuable to wildlife; fruit drop can be messy; good shade tree Large, spreading tree that requires regular watering to reach full potential; Fraxinus berlandieriana Oleaceae Mexican Ash, Fresno X X X X Bi 50' 75' Medium 75' P, D Spring Greenish papery, winged fruits on female trees only Very fast growing tree, but relatively Tepeguaje, Lead Leucaena pulverulenta Fabaceae X X Be 40' 50' Fast 50' P, D Spring Summer White short lived; limbs brittle and break easily, Tree and subject to girdling beetles Dense shade tree provides important -

Guaiacum Sanctum Country – MEXICO Original Language – English

NDF WORKSHOP CASE STUDIES WG 1 – Trees CASE STUDY 7 Guaiacum sanctum Country – MEXICO Original language – English NON-DETRIMENT FINDINGS REPORT ON GUAIACUM SANCTUM IN MEXICO AUTHORS: Leonel López-Toledo David F.R.P. Burslem Miguel Martínez-Ramos Alejandra García-Naranjo I. BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE TAXA 1. BIOLOGICAL DATA 1.1. Scientific and common names Guaiacum sanctum, Linnaeus (1753). Most authors identify four or six species in the genus Guaiacum. Four different synonyms have been recognized for G. sanctum: 1.Guaiacum multijugum Stokes (1812). 2.Guaiacum guatemalense Planch. ex Vail & Rydberg likely to be an hybrid between G. sanctum and G. coulteri (Porter 1972). 3. Guaiacum sloanei Shuttl. ex A. Gray (Gray 1897, Vail & Rydberg 1910). 4.Guaiacum verticale Orteg. (Gray 1897, Vail & Rydberg 1910). Guaiacum sanctum is commonly called lignum vitae in English, and guayacan or palo santo in Spanish. Guaiacum coulteri, a very similar species to G. sanctum, is also called guayacan or lignum vitae. 1.2. Distribution Guaiacum sanctum is found in Mexico, Nicaragua, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, the United States (Florida), Costa Rica, Guatemala, Bahamas, Haiti, Cuba, Honduras, El Salvador, Trinidad and Tobago, and the Turks & Caicos Islands. In some of these countries, G. sanctum has become endangered or is virtually extinct. The Mexican populations cover a greater portion of the species’ natural range than those in any other country. There is no data available for the global population. However, a worldwide analysis of the tropical dry forest estimated a remaining range of 131,087 km2 for North and Central America including Mexico. In general this coincides with presence information of G. -

A Selection of Flowering Shrubs and Trees for Color in Miami-Dade Landscapes

A Selection of Flowering Shrubs and Trees for Color in Miami-Dade Landscapes If no ‘Season for Flowering’ is indicated, flowering occurs periodically throughout the year (usually less so in cooler weather). If water needs are not shown (see key below: drought tolerance/need for moist soil), provide supplemental water once per week to established plants in prolonged hot dry conditions; reduce frequency during cooler winter weather. KEY: sm.tr - Small tree; lg.tr - Large tree; shr – Shrub; cl.sh - Climbing shrub (requires some support); m - Moist soil (limited drought tolerance); dr - Drought Tolerant; fs - Full sun; ss - Some shade. Shrub/Tree Season for Flowering WHITE Beaumontia grandiflora (cl.sh; fs) -> winter (Herald’s Trumpet)1 Brunfelsia jamaicensis (shr; ss; m) -> late fall – winter (Jamaica Raintree)1 Ceiba insignis (lg.tr; fs; dr) -> fall (White Silk Floss Tree) Cordia boissieri (sm.tr; fs; dr) (Texas white olive)2 Dombeya burgessiae (shr; fs) cream – pale pink -> late fall – winter (Apple Blossom, Pink Pear Blossom)1 Eranthemum nigrum (see E. pulchellum below) (Ebony) Euphorbia leucophylla (shr/sm.tr; fs) white/pink -> winter (Little Christmas Tree, Pascuita)1, 2 Fagrea ceylanica (shr/sm.tr; fs/ss; dr) (Ceylon Fagrea) 1,2 Gardenia taitensis (shr/sm.tr; fs; dr) (Tahitian Gardenia)1,2 Jacquinia arborea, J. keyensis (sm.tr/shr; fs; dr) -> spring – summer (Bracelet Wood)1 (Joewood) 1, 2 1 Fragrant 2 Adapts especially well to limestone Kopsia pruniformis (shr/sm.tr; fs/ss.)♣ (Java plum) Mandevilla boliviensis (cl.sh/ss) -> spring -

Woody and Herbaceous Plants Native to Haiti for Use in Miami-Dade Landscapes1

Woody and Herbaceous Plants Native to Haiti For use in Miami-Dade Landscapes1 Haiti occupies the western one third of the island of Hispaniola with the Dominican Republic the remainder. Of all the islands within the Caribbean basin Hispaniola possesses the most varied flora after that of Cuba. The plants contained in this review have been recorded as native to Haiti, though some may now have been extirpated due in large part to severe deforestation. Less than 1.5% of the country’s original tree-cover remains. Haiti’s future is critically tied to re- forestation; loss of tree cover has been so profound that exotic fast growing trees, rather than native species, are being used to halt soil erosion and lessen the risk of mudslides. For more information concerning Haiti’s ecological plight consult references at the end of this document. For present purposes all of the trees listed below are native to Haiti, which is why non-natives such as mango (the most widely planted tree) and other important trees such as citrus, kassod tree (Senna siamea) and lead tree (Leucanea leucocephala) are not included. The latter two trees are among the fast growing species used for re-forestation. The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s Flora of the West Indies was an invaluable tool in assessing the range of plants native to Haiti. Not surprisingly many of the listed trees and shrubs 1 John McLaughlin Ph.D. U.F./Miami-Dade County Extension Office, Homestead, FL 33030 Page | 1 are found in other parts of the Caribbean with some also native to South Florida. -

Syphilis - Its Early History and Treatment Until Penicillin, and the Debate on Its Origins

History Syphilis - Its Early History and Treatment Until Penicillin, and the Debate on its Origins John Frith, RFD Introduction well as other factors such as education, prophylaxis, training of health personnel and adequate and rapid “If I were asked which is the most access to treatment. destructive of all diseases I should unhesitatingly reply, it is that which Up until the early 20th century it was believed that for some years has been raging with syphilis had been brought from America and the New impunity ... What contagion does World to the Old World by Christopher Columbus in thus invade the whole body, so much 1493. In 1934 a new hypothesis was put forward, resist medical art, becomes inoculated that syphilis had previously existed in the Old World so readily, and so cruelly tortures the before Columbus. I In the 1980’s palaeopathological patient ?” Desiderius Erasmus, 1520.1 studies found possible evidence that supported this hypothesis and that syphilis was an old treponeal In 1495 an epidemic of a new and terrible disease broke disease which in the late 15th century had suddenly out among the soldiers of Charles VIII of France when evolved to become different and more virulent. Some he invaded Naples in the first of the Italian Wars, and recent studies however have indicated that this is not its subsequent impact on the peoples of Europe was the case and it still may be a new epidemic venereal devastating – this was syphilis, or grande verole, the disease introduced by Columbus from America. “great pox”. Although it didn’t have the horrendous mortality of the bubonic plague, its symptoms were The first epidemic of the ‘Disease of Naples’ or the painful and repulsive – the appearance of genital ‘French disease’ in Naples 1495 sores, followed by foul abscesses and ulcers over the rest of the body and severe pains. -

FEMA GRAS Assessment of Natural Flavor Complexes: Lavender, Guaiac Coriander-Derived and Related Flavoring Ingredients

Food and Chemical Toxicology 145 (2020) 111584 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Food and Chemical Toxicology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foodchemtox FEMA GRAS assessment of natural flavor complexes: Lavender, Guaiac Coriander-derived and related flavoring ingredients Shoji Fukushima, M.D., Ph.D. a, Samuel M. Cohen, M.D., Ph.D. b, Gerhard Eisenbrand, Ph.D. d, Nigel J. Gooderham, Ph.D. e, F. Peter Guengerich, Ph.D. f, Stephen S. Hecht, Ph.D. g, Ivonne M.C. M. Rietjens, Ph.D., Professor of Toxicology c, Thomas J. Rosol, DVM, PhD, MBA h, Jeanne M. Davidsen, Ph.D. i, Christie L. Harman, MPH i, Vivian Lu i, Sean V. Taylor, Ph.D. i,* a Japan Bioassay Research Center ,2445 Hirasawa, Hadano, Kanagawa 257-0015, Japan b Havlik–Wall Professor of Oncology, Dept. of Pathology and Microbiology, University of Nebraska Medical Center., 983135 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-3135, USA c Division of Toxicology, Wageningen University, Stippeneng 4, 6708 WE Wageningen, The Netherlands d Senior Research Professor of Food Chemistry & Toxicology, University of Kaiserslautern (Retired), Kühler Grund 48/1, 69126 Heidelberg, Germany e Dept. of Metabolism, Digestion and Reproduction, Imperial College London, Sir Alexander Fleming Building, London SW7 2AZ, United Kingdom f Tadashi Inagami Professor of Biochemistry, Dept. of Biochemistry, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN 37232-0146, USA g Wallin Professor of Cancer Prevention, Masonic Cancer Center, Dept. of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Minnesota, MMC 806, 420 Delaware St., S. E., Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA h Department of Biomedical Sciences, Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Ohio University, 1 Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701, USA i Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association, 1101 17th Street NW, Suite 700, Washington, DC 20036, USA ABSTRACT In 2015, the Expert Panel of the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association (FEMA) initiated a program for the re-evaluation of the safety of over 250 natural flavor complexes (NFCs) used as flavor ingredients. -

Atocha Wooden Bed Post, Tag #85413

Mel Fisher’s Treasures – On-Line Research Archives Document ©2019 MOTIVATION, INC Atocha Wooden Bed Post, Tag #85413 By James Sinclair, MA Perhaps one of the more unique finds from the Atocha over the past permit period is that of a turned wooden bed post. Turned Lignum Vitae Bed Post, tag #85413, found by the Dare on 10-18-2014 Length: 144.8 cm. Width: 9.5 cm. Min. Width: 15 mm Weight 8.4 kg. This fragment of opulent furniture was located not far from the Primary Cultural Deposit. The Wood was so hard that when first located crew believed that the object might be modern. The first order of investigation was to identify the type of wood that the bed post was made of. For wood identification we have used the services of; Alden Identification Service 3560 Brookeside Drive Chesapeake Beach, MD 20732 http://woodid.homestead.com/ais.html Property of Motivation, Inc. – PuBlished on Mel Fisher’s Treasures On-Line Research Archives Page 1 of 3 Mel Fisher’s Treasures – On-Line Research Archives Document ©2019 MOTIVATION, INC Dr. Alden identified our post as Lignum Vitae (from Latin “Tree of Life”) a portion of the report follows: 1 - Furniture Lignum-vitae Guaiacum sp. Lignum-vitae (Guaiacum spp. L. /Zygophyllaceae), also known as Guayacan or Gai"ac, is composed of aBout 5 species of slow growing shruBs and trees in the Caltrop Family (Zygophyllaceae), native to subtropical and tropical regions of Central and South America. The five recognized species are: 1. Guaiacum angustifolium Engelm. -Texas Lignum-vitae (Texas, Northeastern Mexico) 2. -

Guaiacum Officinale L

Guaiacum officinale L. JOHN K. FRANCIS International Institute of Tropical Forestry, USDA Forest Service ZYGOPHYLLACEAE (CALTROP FAMILY) No synonyms G Bois de gaoac, bois saint, common lignumvitae, gaïac, gaïac franc, gaïc mâle, guayacán, guayacán colombiano, guayacán de playa, guayacán negro, guayaco, lignumvitae, palo santo, pau santo, pokhout, wayacá (Little and Wadsworth 1964) The native range of Guaiacum officinale includes the South this wood have been used for hundreds of years in herbal med- Caicos in the Bahamas, the Greater Antilles, most of the Less- icine, although they are dangerous in large doses. For its beau- er Antilles, coastal areas of Venezuela and Colombia, and tiful flowers, fruits, and foliage, the species is widely planted as Panama. The species is also native to Aruba, Bonaire, Curacao, an ornamental, especially in the Caribbean area. and Tobago. Although present in Trinidad and Guyana, it may Flowering lasts for about 1 month and may occur from not be native there. However, because of development, har- early spring to fall in Puerto Rico (Little and Wadsworth 1964) vest, and fires, G. officinale is extinct or near extinction on sev- and from March through May in Cuba (Betancourt Barroso eral Caribbean islands. The tree is planted as an ornamental in 1987). Not all trees in a stand flower at the same time. Trees in Bermuda, Florida, and other tropical areas (Francis 1993). one forest planting began flowering and fruiting about 25 Guaiacum officinale is a slow-growing, small to medium- years after planting (Francis 1993). The 2-cm-wide blue flow- sized tree that reaches 3 to 10 m in height.