Transforming Cemeteries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mulch Your Trees and Your Garden with Excellent Wood

Friends of Trees EUGENE CHAPTER Summer, 2013; Vol. 3, No.2 The Trees of Pioneer Cemetery By Whitey Lueck miles to the northeast, ris- One of the aspects of Eugene Pioneer Cemetery that ing abruptly appeals most to the casual visitor is its landscape dominated from the val- by large conifers. Few visitors, however, are aware of the ley floor, were site’s landscape history, and how dramatically it has changed the relatively since the cemetery’s inception in 1872. lofty summits At that time, not a single tree stood on the present site. of the Coburg And it’s not because all of the trees that had once grown Hills. there were cut down by early settlers. Rather, this site—like One of most of present-day Eugene—had been treeless for millen- the first tasks nia due to the cultural practices of the area’s aborigines who that cemetery set fire to the valley floor on a nearly annual basis, thus pre- caretakers had venting trees from getting established. was getting Although the cemetery site itself was originally treeless, trees estab- a visitor could have seen trees in the distance, as the banks lished. Most of of the Willamette River were heavily wooded with maple, the trees that cottonwood, alder, and Douglas-fir. And on the nearby local nurseries hillsides, widely spaced oaks—both Oregon white and Cali- at that time fornia black— could be seen, as well as scattered conifers raised were including valley ponderosa pine and Douglas-fir. Pioneer Cemetery, circa 1936 fruit- and nut- bearing trees It’s hard to imagine these days, but the view from the that provided food. -

National Register of Historic Places Weekly Lists for 1997

National Register of Historic Places 1997 Weekly Lists WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 12/23/96 THROUGH 12/27/96 .................................... 3 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 12/30/96 THROUGH 1/03/97 ...................................... 5 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/06/97 THROUGH 1/10/97 ........................................ 8 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/13/97 THROUGH 1/17/97 ...................................... 12 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/20/97 THROUGH 1/25/97 ...................................... 14 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/27/97 THROUGH 1/31/97 ...................................... 16 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/03/97 THROUGH 2/07/97 ...................................... 19 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/10/97 THROUGH 2/14/97 ...................................... 21 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/17/97 THROUGH 2/21/97 ...................................... 25 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/24/97 THROUGH 2/28/97 ...................................... 28 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/03/97 THROUGH 3/08/97 ...................................... 32 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/10/97 THROUGH 3/14/97 ...................................... 34 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/17/97 THROUGH 3/21/97 ...................................... 36 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/24/97 THROUGH 3/28/97 ...................................... 39 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/31/97 THROUGH 4/04/97 ...................................... 41 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 4/07/97 THROUGH 4/11/97 ...................................... 43 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 4/14/97 THROUGH 4/18/97 ..................................... -

GRAND ISLAND VETERANS HOME (GIVH) (Formerly NEBRASKA SOLDIER and SAILORS HOME) 1887-2005 215 Cubic Ft; 211 Boxes & 36 Volumes

1 RG97 Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) GRAND ISLAND VETERANS HOME (GIVH) (formerly NEBRASKA SOLDIER AND SAILORS HOME) 1887-2005 215 cubic ft; 211 boxes & 36 volumes History of Collection: The Grand Island Veterans Home, originally known as the Nebraska Soldiers and Sailors Home, opened in 1887 and was the first Veterans’ home in the state. A brief history of the facility is reproduced below from the DHHS website at: http://dhhs.ne.gov/Documents/GIVHHistory.pdf History of the Grand Island Veterans’ Home Nebraska’s oldest and largest home was established in 1887. The following is an excerpt taken from the Senate Journal of the Legislature of the State of Nebraska Twentieth Regular Session held in Lincoln on January 4, 1887: “WHEREAS, There are many old soldiers in Nebraska who, from wounds or disabilities received while in the union army during the rebellion, are in the county poorhouses of this state; therefore be it RESOLVED, That it is the sense of this Senate that a suitable building be erected and grounds provided for the care and comfort of the old soldiers of Nebraska in their declining years; RESOLVED, That a committee of five be appointed to confer with a committee of the House on indigent soldiers and marines to take such action as will look to the establishment of a State Soldiers’ Home.” Legislative Bill 247 was passed on March 4, 1887 for the establishment of a soldiers’ home and the bill stipulated that not less than 640 acres be donated for the site. The Grand Island Board of Trade had a committee meeting with the citizens of Grand Island to secure funds to purchase land for the site of the home. -

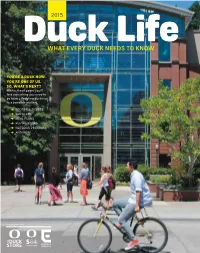

What Every Duck Needs to Know

2015 DuckWHAT EVERY DUCK NEEDS Life TO KNOW YOU’RE A DUCK NOW. YOU’RE ONE OF US. SO, WHAT’S NEXT? Within these pages you’ll find everything you need to go from a fledgling duckling to a bonafide mallard. ➜ FOOTBALL TICKETS ➜ GREEK LIFE ➜ MEAL PLANS ➜ BUYING BOOKS ➜ OUTDOOR PROGRAM ➜ AND MORE... content sponsored by: NEW STUDENT HOUSING OPENING FALL 2015 SIGN A LEASE IN A 4 BED + 4 BATH A OR B FLOOR PLAN & SAVE VISIT 2125FRANKLIN.COM TO SEE OUR CURRENT LEASING SPECIALS + SAVE $150 WITH ZERO DOWN HOW DO WE COMPARE? MEAL PLAN REQUIRED? SUMMER INCLUDED? TOTAL 2125 FRANKLIN shared bed + shared bath NO YES $6,588 RESIDENCE HALLS shared bed + shared bath YES NO $11,430-$16,645* 2125 FRANKLIN private bed + private bath NO YES $7,908-$8,628 RESIDENCE HALLS private bed + private or shared bath YES NO $12,582-$19,786* HARD HAT TOURS — EVERY TUES. & WED. FROM 4-5PM TOURS BEGIN AT THE 2125 FRANKLIN LEASING OFFICE & ARE LIMITED TO 10 PEOPLE AT A TIME Rates & fees are subject to change. Limited time only. While supplies last. Total includes 16 meals per week. Total does not include cost for summer. Information accurate as of 5/19/15 — https:housing.uoregon.edu COUPON COBURG RD. Student Special Oakway Golf Course 2000 Cal Young Rd CAL YOUNG RD. 50% OAKWAY RD. OFFwith valid Student ID COBURG RD. $9 for Ferrry Street Bridge 18 holes Willamette River $5 for BROADWAY FRANKLIN BLV 9 holes D OAKWAY GOLF COURSE University of Oregon Bring entire ad to course. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A)

NPS Form 10-900 __. _.. ., 1,__^—•% OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) ! r. ', United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places I Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Women's Memorial Quadrangle Ensemble other names/site number 2. Location street & number _ University of Oregon Campus not for publication city or town ___ Eugene vicinity state Oregon code OR county ___Lane_ codeQ39__ zip code 97403 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this 0 nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property B meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally Q statewide D locally. -

Matthew Dennis Curriculum Vitae

Matthew Dennis Curriculum Vitae Mailing Addresses: Department of History 1288 University of Oregon Eugene, OR 97403 [email protected] Education Ph.D. University of California, Berkeley, December 1986. M.A. University of California, Berkeley, December 1979. A.B., A.B., University of California, Irvine, June 1977, History and Political Science. Teaching Fields Colonial and early national America; American cultural and environmental history; public memory and commemoration; American cities; American Indian history. Positions July 2015-present: Professor Emeritus of History and Professor Emeritus of Environmental Studies. September 2002-June 2015: Professor of History; Professor of Environmental Studies, University of Oregon. Spring 2002: Visiting Professor (maître de conférennces invité) à l’Université Paris VII—Denis Diderot, Institut d’anglais Charles V. September 1994-2002: Associate Professor of History, University of Oregon. September 1988-1994: Assistant Professor of History, University of Oregon. August 1987-July 1988: Rockefeller Foundation Fellow, D’Arcy McNickle Center for the History of the American Indian, Newberry Library, Chicago. 1986-1987: Visiting Lecturer, Department of History, University of California, Riverside. Major Publications, Books Seneca Possessed: Indians, Witchcraft, and Power in the Early American Republic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010; paper 2012). Encyclopedia of Holidays and Celebrations: A Country by Country Guide, general editor (with an introduction), 3 vols. (New York: Facts of File, 2006), 1852 pp.; named a “Best Reference Source, 2006” by Library Journal. Red, White, and Blue Letter Days: An American Calendar (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2002; paper 2005). Revelry and Riot in Early America, co-edited with William Pencak and Simon Newman (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2002). -

UO Summary Table of Historic Rankings and Designations

University Of Oregon Summary Table of Historic Rankings and Designations for Landscapes, Structures, and Buildings Campus Planning, Design and Construction - 11/18/15 The following table provides a summary of the historic resources' rankings and designations. Resources are ranked according to their historical significance and integrity (see key at the end of this document for a descriptions of each ranking). This document is intended to be used with the University of Oregon's Historic Properties Map. For further information on a particular resource, please refer to the associated survey forms. Prior to performing work on campus (repairs, alterations, etc.), refer to this document and the associated University of Oregon Historic Properties Map. Also, refer to the Summary of Historic Preservation Regulations, which describes the steps required to ensure the UO meets all city, state, and federal historic preservation requirements. NOTE: This list does not include all individual landscape features such as educational and memorial trees, plaques, memorials and sculptures. Please contact Campus Planning, Design and Construction. NAME OTHER ASSOCIATED ADDRESS SUMMARY OF HISTORIC DESIGNATION (key at end) ADDITIONAL DATA NAMES State Historic Preservation City of Eugene Designation Notes Date of Official Office (SHPO) Designation (key at end) # Street Consruction Architect UO Ranking Reference Date Designation Date Ranking Reference Date Ranking Reference Date OPEN SPACES 13th Ave. Axis 13th Ave. Pre 1900 Primary CHLP 2006 15th Ave. Axis 15th Ave. Post 1914 Tertiary CHLP Survey 2006 Amphitheater Green 1950-1998 Non-Contributing CHLP Survey 2006 U of O Campus, Campus Plan 1914 1914 Plan 1914 Lawrence & Holford Primary Lawrence Survey 1989 OSBHE Ranking: Mentioned. -

Historic Mt. Crest Abbey Mausoleum “The Call of a Better Way”

Historic Mt. Crest Abbey Mausoleum at City View Cemetery 100th Anniversary 1914-2014 Walking Tour “The Call of a Better Way” You are invited to take a walking tour of the historic Mt. Crest Abbey Mausoleum. This self-guided tour packet includes a brief history of Mt. Crest Abbey, a map of the mausoleum, and the personal history of significant members of Salem’s community interred within the mausoleum. Feel free to stay as long as you like. Staff members will be available in the Funeral Home to answer any questions you may have. During pre-war optimism of the early 1900s--the Progressive Era--many people believed that technology and science were advancing rapidly. This also applied to their view of burial. The modern age of the mausoleum and the “Call of a Better Way” began, even though above-ground entombment is a long-standing custom. A mausoleum is an alternative to ground burial. It offers crypts for entombment and niches for cremation. It is dry, clean and secure, and protected from the elements. Mt. Crest Abbey was built by the Portland Mausoleum Company, and its construction was completed in the spring of 1914. Mt. Crest Abbey was dedicated on Memorial Day, May 30th of that year. The mausoleum is one of six similar mausoleums built by the Portland Mausoleum Company in Oregon between 1910 and 1919. The Portland Mausoleum Company went out of business in 1929--the same year that ushered in the Great Depression. Mt. Crest Abbey was designed by prominent architect Ellis Lawrence of Portland and his firm Lawrence & Holford. -

Phase I Environmental Site Assessment of 102730007 250

PHASE I ENVIRONMENTAL SITE ASSESSMENT OF 102730007 250 INTERNATIONAL WAY SPRINGFIELD, OR 97477 PREMIER PROJECT NO. 210314.00 October 14, 2010 Prepared by: Prepared For: Premier Environmental Services, Inc. FDIC, CBRE and Realogy c/o NRT REO 1880 West Oak Parkway Experts Marietta, GA 30062 2001 Ross Avenue, Suite 3400 Phone: 800.708.8525 Dallas , TX 75201 Fax: 866.263.0098 Attn. Jason Spalding Phase I Environmental Site Assessment October 14, 2010 250 International Way, Springfield, OR TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION.....................................................................................................1 2.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.........................................................................................................2 3.0 SCOPE OF WORK AND LIMITATIONS..................................................................................4 4.0 SITE BACKGROUND............................................................................................................. 6 5.0 PROPERTY HISTORY............................................................................................................ 7 5.1 Historic Uses of the Property...................................................................................................7 5.2 Historic Uses of the Adjoining Properties................................................................................ 8 6.0 REGULATORY REVIEW.........................................................................................................9 6.1 Standard Environmental Records -

Campus Physical Framework Vision B B

0 UNIVERSITYArea Studies OF OREGON CAMPUS PHYSICAL FRAMEWORK VISION B B UNIVERSITY OF OREGON CAMPUS PHYSICAL FRAMEWORK VISION PURPOSE AND PUBLIC OUTREACH The University of Oregon Campus Physical Framework Vision (UOCPFV) presents a comprehensive physical structure for the campus. This document is a resource to the university’s Campus Plan. It provides greater specifcity to inform decisions, to accommodate growth and change, and to ensure enhancement of the beauty, legacy, and function of the campus The UOCPFV identifes a campus framework of open spaces and pedestrian connectors. The landscape-centric focus builds on the campus’s cultural landscape heritage, frst envisioned more than a century ago by Ellis Lawrence, campus architect, and Fred Cuthbert, campus landscape architect, and manifested in bold landscape treatments such as the Old Campus Quadrangle and the Memorial Quadrangle. Recommendations from the UOCPFV may lead to updates to the Campus Plan 15 March 2016 UNIVERSITY OF OREGON CAMPUS PHYSICAL FRAMEWORK VISION FOREWORD D FOREWORD By intent, university campuses are collegial. Each is a community Thoughtful campus leaders are reassessing the values that foster The University of Oregon is housed on a mature 295-acre campus. interconnected in its mission to gather, create, and distribute their campus culture and unique sense of place. And many The university’s 2005 Campus Plan (updated in 2011 and amended knowledge. The ideal of campus planning and design is to defne universities are reexamining their campuses, to understand the in 2014) outlines a series of procedures and policies to use as a physical framework vision for an intellectual, social, and cultural essential elements of their physical makeup and how to best link development projects are designed and executed. -

Genealogical Forum of Oregon, Inc. Portland, Oregon

of the Genealogical Forum of Oregon, Inc. Portland, Oregon Volume 58, Number 4 June 2009 GENEALOGICAL FORUM OF OREGON 1505 SE Gideon Street • P.O. Box 42567, Portland, Oregon 97242-0567 voice or fax: 503-963-1932 • website: www.gfo.org OFFICERS THE BULLETIN President . .Lyleth Winther Coordinator: Peggy Baldwin Vice President . Janet Irwin Bulletin Editorial Team: Secretary . Gwen. Newborg Judi Scott, Carol Surrency, Susan LeBlanc, Treasurer . Jeanette. Hopkins Mickey Sieracki Directors-at-Large . Bruce Conrad, Cathy Lauer Column Editors: Peggy Baldwin, Janis Bowlby, Rex Endowment Committee . Marty. Krauter Bosse, Eileen Chamberlin, Connie Lenzen, Alene Reaugh, Judi Scott, Harvey Steele, Carol Ralston MEMBERSHIP Surrency, Lyleth Winther Layout& Design: Diane Wagner $40 Individual - 12 months - OR - $80 -25 months Proofreader: Bonnie LaDoe (The Bulletin & Insider will be mailed to your listed address) Deadlines for submissions $35 Individual - 12 months - OR - $70 Individual - to the BULLETIN: 25 months . Discount for Bulletin & Insider received by e-mail) September issue – July 1; December issue – October 1; $55 Joint* - 12 months - OR - $100 Joint* - 25 months March issue – January 1; June issue – April 1 *A joint membership is for two people who live at the same address; you may specifiy two e-mail Send submissions to: addresses . (Discount for Bulletin & Insider [email protected] received by e-mail ). $15 Student Opinions expressed in the Bulletin are not necessarily those $20 Libraries & Societies of the Genealogical Forum of Oregon, Inc . The society is a $750 Life-Individual ~ (Also available in non-profit organization as classified by the Internal Revenue 3 annual payments of $270) Service . As such, gifts, contributions, and devices made to $1,000 Life-Joint* ~ (Also available in the Society are 100 percent tax deductible to the donors . -

River View Cemetery Historic Overview

River View Cemetery Historic Overview River View Cemetery, circa 1901 Prepared by George Kramer, M.S., HP Senior Preservation Specialist Heritage Research Associates, Inc. Eugene, Oregon October 2011 Heritage Research Associates Report No. 355 River View Cemetery Historic Overview Prepared by George Kramer, M.S., HP Senior Preservation Specialist Prepared for TyLin International 285 Liberty Street NE #350 Salem, OR 97301 and Multnomah County, Oregon Heritage Research Associates, Inc. 1997 Garden Avenue Eugene, Oregon October 2011 Heritage Research Associates Report No. 355 River View Cemetery - Historic Overview October 2011 Introduction River View Cemetery (sometimes mis-identified as Riverview) is a 300+ acre wooded and landscaped enclave located at the southwest corner of the intersection of Macadam Avenue and Taylor‟s Ferry Road, near the Sellwood Bridge, in Portland, Oregon. River View was established on land purchased by Henry W. Corbett and then sold on an interest-free note to the River View Cemetery Association, an organization formed by Corbett in association with Henry Failing, William S. Ladd and others. The Association adopted its initial bylaws on December 4, 1882 and remains a non-profit endowment care facility. “Owners of Interment rights in the cemetery become part of the River View Cemetery Association, thereby becoming owners of the cemetery” (River View, c2011). From its beginnings, River View Cemetery was seen as a major milestone in Portland‟s development; a beautiful, serene, well-designed and maintained final resting place for the city‟s dead. Its graceful, almost park-like, natural setting quickly became a popular recreational destination for Portlanders, complimenting the project‟s primary purpose.